Native American artists, especially women, have only recently gained a spotlight within the mainstream art world. For centuries, Native art was siloed on reservations, at trading posts, and in Indian markets, with no dedicated Indigenous commercial galleries either in urban Indian centers like New York City, San Francisco, Tulsa, or Phoenix or in other areas with significant Native populations. But lately they are finding their way into major galleries and institutions from Miami to New York to Venice.

For Women’s History Month, we delve into art from 15 Native American, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian women. While not an exhaustive list, these artists represent a broad spectrum of artistic innovation spanning multiple generations and mediums, from foundational pottery to contemporary Ravenstail weaving. Shattering conventional ideas about fine art while honoring historical techniques and cultural knowledge, they underscore the vitality of Indigenous women’s contributions to contemporary art and the ongoing need to ensure that their voices and visions are centered in mainstream art discourse.

Read more of our Women’s History Month coverage here.

-

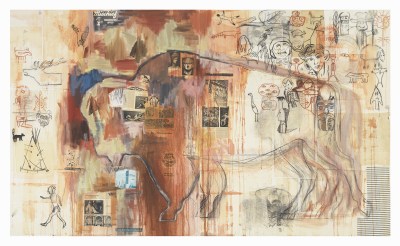

Athena LaTocha

Image Credit: Collection of Mary & Matthew Ho, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist. Athena LaTocha (b. 1969) is a Hunkpapa Lakota and Ojibwe artist based in Brooklyn whose monumental works exist somewhere between painting and environmental art. Previously a smaller-scale painter, she now creates giant pieces by laying resin-coated photographic paper on the floor and then pouring onto them ink, soil, and other materials, allowing them to permeate the surface before scraping off the detritus.

Referencing the history of Native lands, from Mexican mesas and Ozark bluffs to Louisiana wetlands, LaTocha’s compositions have recently focused on New York City as a subject. LaTocha visits construction sites and cemeteries to collect materials and dirt once in contact with the city’s original people, commemorating the Lenape of New York now in Oklahoma. Landscape painting becomes literal in LaTocha’s creations as she embeds these earthly remains into her paper supports. Lately the artist’s work has gone deeper, with the artist photographing and recording ambient sound at construction sites for her latest line of work: immersive shows recently on view at 601 Artspace in Manhattan and Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut.

-

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Image Credit: Courtesy of the Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (1940–2025) was a groundbreaking visual artist, curator, and activist, and an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation. She worked tirelessly to break the “buckskin ceiling,” helping pave the way for a new Native vanguard of Indigenous artists. Her vast oeuvre, developed over 50 years, deployed incisive political humor and poetic style and spanned painting, collage, drawing, print, and sculpture. Her works gesture to the land, culture, ontology, and cosmology of Native peoples, asserting sovereignty in her representation of tribes’ past, present, and future. A show she curated, “Indigenous Identities: Here, Now & Always,” is currently on view at the Zimmerli Art Museum in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and features more than 100 works by 97 artists.

-

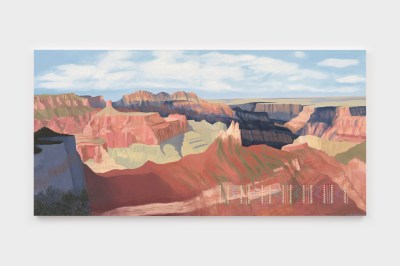

Kay WalkingStick

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Hales, London and New York. Photo: JSP Art Photography. The Cherokee-Irish painter and sculptor Kay WalkingStick (b. 1935) inscribes Indigenous motifs on her landscape paintings to create a different kind of cartography, one presenting the views from a pre-contact vantage point. The specific sites she depicts—the Grand Canyon, Glacier National Park, Sun Valley—are known for tourism and recreation, and her paintings can be seen as referencing the Native communities displaced onto reservations to make these iconic travel destinations.

Featured at the 2024 Venice Biennale, WalkingStick is experiencing a significant moment of recognition. But she is not doing anything differently now than she has in the past. In the 1970s she was profoundly affected by the American Indian Movement of that period, when she produced a series of honorific paintings spurred by an absent father and a conversation with him near the end of his life about Cherokee heritage. Archetypal Image (1975), for example, draws from both Native and American symbols—from tipis to Manhattan’s bridges, whose maintenance nets become a metaphor for the cloth and hides shaping traditional Native dwellings.

-

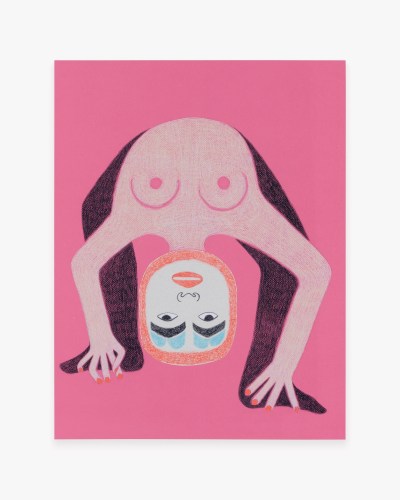

Rachel Martin

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist. Rachel Martin (b. 1954) is a Tlingít artist and enrolled member of the Tsaagweideí, Killer Whale Clan, of the Yellow Cedar House (X̱aai Hit´) Eagle Moiety. She grew up in California and Montana and now resides in New York City. Working primarily in sculpture and drawing, Martin is an inheritor of the Pacific Northwest line drawing tradition, whose cosmological symbols—like bears, fish, and frogs—she melds with contemporary cultural references and places in cheeky and feminist tableaux.

Bending the Rules (2024), in colored pencil on paper with a collaged mask, features a bare-chested woman turned upside down, facing the viewer with lips slightly apart. Been Ready (2023) offers the same whimsicality, with a Tlingít mask cutout serving as the head of a woman in profile, her cutout legs in mid-sprint. The mask has a stuck-out tongue, Martin’s gesture toward the trickster archetype in Tlingít mythology. Martin received a Forge Project fellowship in upstate New York in 2023 and, in 2024, had solo exhibitions at the Hannah Traore Gallery in New York City and the Nina Johnson Gallery in Miami.

-

Sara Siestreem

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, OR. A Pratt MFA graduate, Sara Siestreem’s practice includes ceramics, photography, weaving, painting, and installation art. Skyline (2024) is a series of Hanis Coos baskets nontraditionally cast in clay and topped in gold, evoking the commodification of Native culture. transtemporal clam basket (2022) is a 3D print of a handwoven basket. Minion (2024) is composed of four ceramic black and white ceremonial caps underpinned by cascading scarlet beads, referencing systemic violence against Indigenous women and girls. Un-ring Bells (2013) incorporates photographs and representations of oyster shells the artist found along the local Coos and Millicoma Rivers’ shores long after the extinction of local tribes, the effect of white settlement and industrial fishing.

-

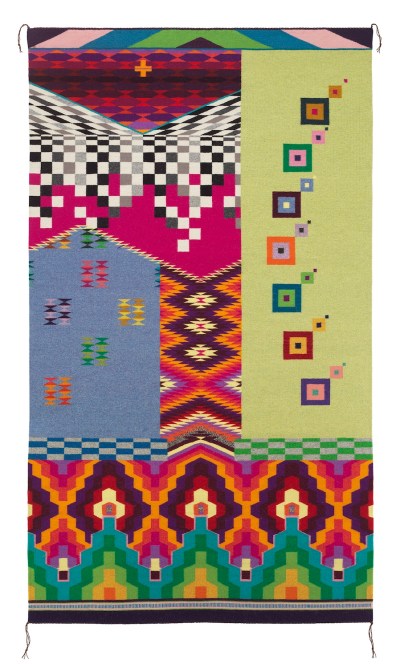

Melissa Cody

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York. Melissa Cody (b. 1983) is a fourth-generation Navajo weaver whose bright and playful show at MoMA PS1 in April 2024 connected traditional weaving to video games, the X- and Y-axes of her gridded patterns conjuring games like Mario Kart and Pac-Man. In her work, Cody also mimics the glitches that recur in older electronic games, explaining, “Glitches and separation of time and space happen; I like being able to kind of make them intentional.” The through line of her flamboyant style can be traced back to the matrilineal guild of weavers who mentored Cody in her youth, teaching her to consider her weaving a time capsule incorporating contemporary norms and the evolving self-definition of the Diné.

-

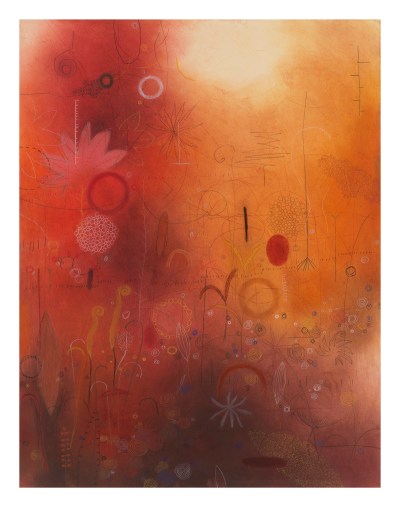

Emmi Whitehorse

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York. A Navajo painter from New Mexico, Emmi Whitehorse (b. 1957) creates layered abstractions influenced by her rural upbringing. Her formative years, followed by a BA in painting from the University of New Mexico, grounded her practice in a worldview deeply rooted in nature. “If you got sick and something was wrong, it meant that psychically you were falling out of rhythm with nature,” she explains. “So you went about healing by surrounding yourself with beauty and nature; that applies to my painting.” Whitehorse’s meditative landscapes incorporate a range of personal symbols; in a signature work, Firelight II (2024), for example, she interweaves abstracted botanical forms, dotted lines, gridded axes, and surveillance drone symbols topped with infinity signs, creating a complex composition that maps both physical terrain and systems of observation.

-

Maria Martinez

Image Credit: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Known as the matriarch of Native American pottery, Maria Martinez (1887–1980) transformed Indigenous ceramics from craft into fine art though her black-on-black pottery technique. Working with her husband, Julian Martinez, and other family members from her home in San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, she achieved what few Native artists of her time could: widespread recognition in the art world. Her timeless black pottery, with matte designs painted by Julian, continues to influence contemporary ceramics and stands as a testament to Indigenous innovation.

Martinez’s journey began with archaeology; she studied ancient pottery shards at a time when earthenware was being abandoned for Spanish tin and English porcelain. She perfected and reinvented historic techniques, creating a distinctive style that art critics would later compare to the best of modernist art and design. Her artistic achievements earned her historic recognition: she met four U.S. presidents, attracted the patronage of the Rockefeller family, and became perhaps the most famous Native American artist in history.

-

Rose B. Simpson

Rose B. Simpson (b. 1983) is a multimedia artist known for her ceramic and metal sculptures, installations, and performance pieces. Her seven sentinel-like figures in Madison Square Park and two in Inwood Park, both in New York, echo the city skyline and invite viewers to self-reflect and consider place and time amidst the frenetic urban landscape.

Born in 1983 in Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, Simpson emerged from a matriarchy of ceramicists. Though accepted to Dartmouth, she chose to attend the University of New Mexico to maintain formative ties to the land. She earned MFAs from the Rhode Island School of Design and the Institute of American Indian Arts in ceramics and creative nonfiction and studied pottery in Japan and South Korea. Her work occupies the intersection of red clay pottery and modern technology, pushing the boundaries of Pueblo art.

-

Dyani White Hawk

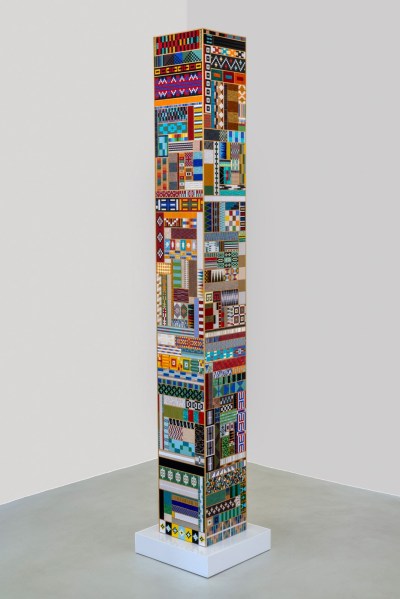

Image Credit: Courtesy of the Artist and Bockley Gallery, Minneapolis, MN. Photo: Rik Sferra. Contemporary multidisciplinary artist and curator Dyani White Hawk (b. 1976) is of Sicangu Lakota and white descent. Born in Madison, Wisconsin, she attended the Institute of American Indian Arts and the University of Wisconsin–Madison and was the curator at the Native-owned All My Relations gallery in Minneapolis from 2010 to 2015 before turning solely to studio practice. In 2022 her work Wopila | Lineage (2022), a 14-by-8-foot work composed of a half million glass bugle beads was included in that year’s Whitney Biennial.

White Hawk draws from both traditional Lakota art forms such as quillwork and beadwork and European easel painting to critique art historical narratives that subordinate Native creations. In all of her work, which in addition to painting and sculpture includes installations, photography, and performances, she promotes the Lakota philosophical and moral principle mitákuye oyás’iŋ: We are all related. White Hawk made this principle literal in early 2024 with the totemic rectangular sculpture Visiting (2024), comprising four collaged panels of beadwork; facing an impossible deadline, White Hawk recruited her family and community to finish the commission, which was shown at the 2024 Armory Show in New York City.

-

Bernice Akamine

Born in Honolulu, Bernice Akamine (1949–2024) was a Native Hawaiian artist whose compositions, installations, and sculptures in paper, glass, and metal deploy traditional techniques to critique the ongoing impact of American colonization on Hawaii. She received an MFA in glass and sculpture from the University of Hawaii in 1999.

Akamine is best known for Kalo, her 87-sculpture installation at the 2019 Hawaiian Biennial that honored the eponymous and ubiquitous local plant and Hui Aloha ‘Āina, an organization supporting Hawaiian sovereignty. Equally political, her work Papahanaumokua (2018) is a series of glass-tipped bullet casings filled with ‘alaea, Hawaiian earth pigments. Inspired by the January 2018 ballistic missile threat alert received (but not taken entirely seriously) by locals already conscious of the number of military sites on the main island, it also refers to the environmental damage caused by those sites to Hawaii’s land and waters. One of her later pieces before her death in 2024, Kapa Moe: Hae Hawaiʻi (2021), is a protest quilt made of kapa plant bark, a rebuke of the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy.

-

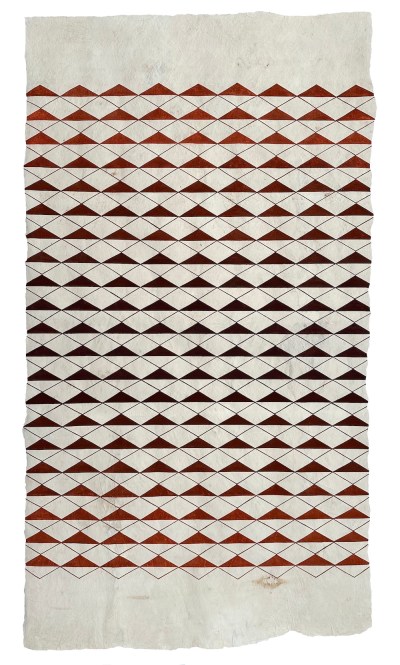

Lehuauakea

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist. Lehuauakea (b. 1996) is a mixed-Native Hawaiian multidisciplinary artist whose work relies on the use of traditional materials and designs while gesturing to the complexity of mixed-Indigenous identity and endangered ecologies of Hawaii. Born in Portland, Oregon, in 1996 and self-identified as māhūwahine, a Native Hawaiian third-gender identity, Lehuauakea developed a focus on kapa, or bark-cloth, painting while attending an all-Native Hawaiian school. She honed her artistic practice at the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Oregon, where she developed her signature kapas using traditional bamboo stamps and natural pigments.

Lehuauakea’s E Hoʻāla Ka Lupe: To Awaken the Kite (2022) honors traditional kites, or lupe, and related mythology. Her work Mele o Nā Kaukani Wai (Song of a Thousand Waters) (2018) at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, points to the need to protect and integrate Indigenous knowledge into Western science to mitigate climate change. Lehuauakea lives and practices kapa-making in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

-

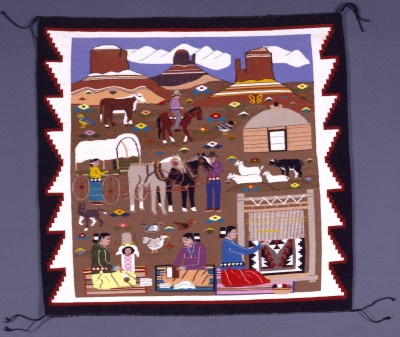

Louise Nez

Image Credit: Smithsonian American Art Museum. In her woven compositions, renowned fourth-generation Diné (Navajo) weaver Louise Nez (b. 1942) depicts scenes of life on the rez. Born in Sand Springs, Arizona, she has made hundreds of weavings in patterns developed during the 19th-century commercialization of Navajo rugs. Not until the 1980s did she begin engaging in pictorial weaving, subverting extant colonial expectations of Diné artists. Her best-known wall hanging, housed by the Smithsonian Museum of Art in Washington, D.C., Reservation Scene (1992), features brightly colored figures weaving, herding, and traveling by 19th-century wagon. Inspired by her grandson’s coloring books, Nez also makes such playful works as Dinosaur Pictorial Weaving (date unknown) retained by the Gochman Collection.

-

Sandra Okuma

Self-taught beader Sandra Okuma (b. 1945) is a Luiseño and Shoshone-Bannock artist whose sumptuous works are influenced by her training as a painter. Hailing from the La Jolla Indian Reservation in California, she has been a fixture of the Santa Fe Indian Market since 1998. Her Beaded Deer Bag (2011) and Beaded Buffalo Bag (2020) are richly colored masterpieces that recognize the animals’ historical centrality to tribal life. While not traditionally recognized as fine art, her sophisticated beadwork has maintained consistent recognition within the Heard Museum Guild Indian Market scene and garnered broad appreciation from the art world.

-

Sydney Akagi

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Pat Barry. Tlingit weaver Sydney Akagi (born 1989) preserves traditional Alaska Native Ravenstail and Chilkat techniques in her labor-intensive masks and mantles. Born in Southeast Alaska and an enrolled member of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, she wove her first wall hanging in 2018 under the guidance of her mentor, weaver Lily Hope. Akagi employs historical motifs declaring a person’s secular and social standing within the tribe, as in Ceremonial Woven Tunic, Ravenstail and Chilkat, a sleeveless ceremonial tunic that she created for the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation. Her works draw from intensive research and design processes while reflecting her current practice of living off the ancient lands of the Lingit Aani.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content