Art has always been connected to the natural world in some way. But around the late 1960s, a generation of artists decided they’d rather make works framed by the great outdoors than by the walls of a gallery, museum, or studio. The land functioned simultaneously as a source of inspiration, a material, and a vast exhibition space.

More than half a century later, curators and scholars are still coming to terms with land art’s expansive range. Earth works could be intimate and ephemeral, not only monumental feats of engineering. They were made for cities as well as the remote reaches of the American West. And despite a serious gender bias in the art history books, land art’s creators were both men and women.

Recent years have seen a flurry of exhibitions and research seeking to redress the historic imbalance. “Groundswell: Women of Land Art,” last year’s survey show at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, highlighted the indispensable role of women artists such as Nancy Holt, Agnes Denes, and Mary Miss in the movement.

Below, we take a closer look at seven essential names to know and where their notable works can be found across America.

Nancy Holt

On the solstices, the tunnels are aligned with the sunrises and sunsets on the horizon. Nancy Holt, Sun Tunnels (1973–76), Great Basin Desert, Utah. © Holt/Smithson Foundation and Dia Art Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo: Nancy Holt, courtesy Holt/Smithson Foundation.

Nancy Holt often created earth works in places that held personal meaning. In New Jersey, where she grew up, she embarked on an ambitious landfill reclamation project, Sky Mound (1984–), that was never fully realized. For Buried Poems (1969–71) she dedicated poems to five different people and buried them in the earth at sites that evoked each person to her.

Holt’s celebrated Sun Tunnels (1973–76) involved three years of visits to Utah’s Great Basin Desert, where she purchased 40 acres of land. Unlike many land art interventions that transformed their sites, Sun Tunnels worked with the existing landscape. Holt placed four monumental concrete cylinders, each 18 feet long and 9 feet in diameter, in a cross formation that framed the sun on the horizon during the winter and summer solstices. They were punctured with a series of “star holes” at eye level, allowing light to speckle on the viewer inside.

Agnes Denes

Agnes Denes, Wheatfield—A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan—With New York Financial Center (1982). Photo: © Agnes Denes, courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects.

For four months in 1982, Agnes Denes tended to a two-acre wheat field she had planted in downtown New York. Using a $10,000 grant from the Public Art Fund, Denes cultivated the ephemeral work in the Battery Park landfill—then one of the last undeveloped parts of Manhattan.

Just one block from Wall Street, it was a potent site chosen as a symbol of the divides between nature and technology, wealth, and poverty. Wheatfield – A Confrontation yielded a traveling exhibition dedicated to “the end of world hunger,” which brought the harvested wheat to 28 cities worldwide. (The hay was gifted to horses of the NYPD.)

After decades away from the limelight in which she planted forests in Finland and Australia, Denes returned to public art in New York in 2015 with The Living Pyramid, a ziggurat overgrown with greenery for Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens.

Mary Miss

Mary Miss, Greenwood Pond-Double Site (1989–96) at the Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, pictured in 1996. Photo: © Mary Miss, courtesy the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Mary Miss started out in the 1970s making sculptures that she placed outside. She soon moved on to site-specific outdoor works that highlight unnoticed parts of the environment, created in dialogue with botanists, ecologists, historians, hydrologists, architects, and public administrators.

One such collaborative creation was South Cove (1984–87), a jetty that curves out from the waterfront at the tip of Manhattan’s Battery Park City. Having lived in Tribeca for years, Miss was inspired by her own frustration at not being able to reach the water’s edge. The work allows visitors to reconnect with the nature around them and see the water differently.

Miss’s major urban wetland project for the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa, Greenwood Pond: Double Site (1989–96), is one of a handful of environmental installations held in the collection of an American museum. But the work has now fallen into disrepair and is under threat of demolition. The museum said the anticipated $2.7 million cost of repairs left it no choice but to dismantle the work entirely. Miss recently moved to save Greenwood Pond and organizations such as the Cultural Landscape Foundation are currently advocating for its protection; this month, the artist won a preliminary injunction to prevent the removal of the work.

Alice Aycock

Alice Aycock, Low Building with Dirt Roof (for Mary) (1973/2010). Photo: Jerry L. Thompson, 2011.

Alice Aycock’s early works in stone, wood, and earth were filled with references to ancient architecture and history. In 1973, she created Low Building with Dirt Roof (for Mary) on Gibney Farm, her family’s property in Pennsylvania, and described it as “nonfunctional architecture.”

In the original version, now lost, the roof was planted with the same crop that was growing in the surrounding fields. Named for Mary, the artist’s young niece who passed away prematurely, the structure was inspired by frontier homes and the underground tunnels and tombs of the ancient Greeks. Aycock recreated the work in 2010 at Storm King Art Center in upstate New York.

Aycock also reconstructed A Simple Network of Underground Wells and Tunnels (2011), a subterranean structure that plays with confinement and expansiveness, darkness and light. Originally installed in New Jersey in 1975, the work was rebuilt for Art Omi in Ghent, New York.

Ana Mendieta

Ana Mendieta, Esculturas Rupestres (Rupestrian Sculptures) (1981), super-8mm film, black and white, silent. Photo: © 2024 The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta inserted herself into much of her work, which spanned film, performance, photography, and sculpture. This was especially true for her Silueta series between 1974 and 1981, where she imprinted her body’s outline into landscapes in Iowa, upstate New York, Florida, and Mexico. Mendieta called the Siluetas “earth-body works” and they were either made by fashioning a silhouette from natural materials such as mud, sticks, flowers, and grass, or by incising it into the earth, at times burning it with gunpowder or fireworks.

Mendieta began the series while visiting pre-Columbian sites in Oaxaca, Mexico, at a time when she was growing more interested in Indigenous rituals. She lay naked in a Zapotec tomb with white flowers strewn across her body.

The series evolved into ancient goddess forms that Mendieta carved into rocks and clay beds, or shaped with sand. It is unclear how many Siluetas still survive in situ, although traces remain of Ceiba Fetish (1981), a figure drawn on the base of a tree in Miami’s Cuban Memorial Park.

Maya Lin

Maya Lin, The Wave Field (1995). Photo: Scott C. Soderberg, Michigan Photography, University of Michigan.

Maya Lin was an architecture student at Yale when she won the national design competition for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., in 1981. Since then, her varied practice has combined environmental art with memorial designs and architectural projects. Tying it all together is her impulse “toward sculpting the earth,” she wrote in her book Boundaries.

She did just that in her famed series of earth works inspired by water waves. The first, The Wave Field (1995), ripples across a 10,000-square-foot patch of lawn on the University of Michigan campus. The grassy rows of waves are visible from ground level or the classrooms above, with some crests reaching six feet. The work grew out of Lin’s interest in aerospace engineering and satellite photography of the ocean.

The series continued with Flutter (2005), located outside Miami’s Federal Courthouse, and Storm King Wavefield (2007–08), on an 11-acre site at the Hudson Valley sculpture park.

Beverly Buchanan

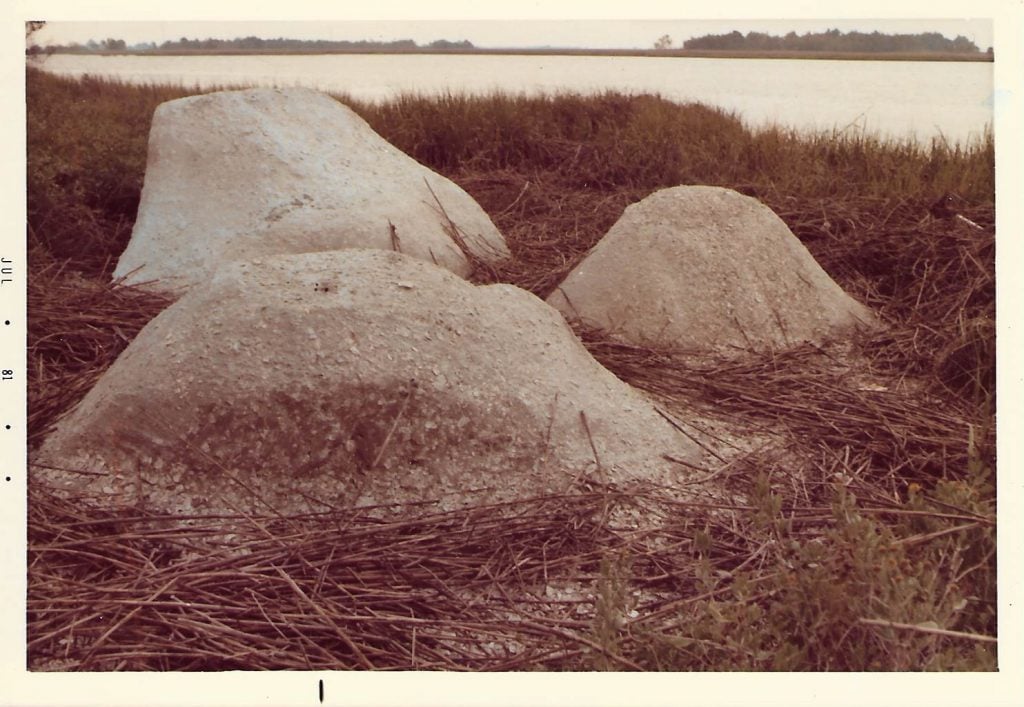

Beverly Buchanan, Marsh Ruins (1981). Photo: courtesy of the Estate of Beverly Buchanan and Andrew Edlin Gallery.

Beverly Buchanan’s unclassifiable works dealt with memory and place, ranging across sculpture, painting, drawing, photography, and performance. A native Southerner, Buchanan was working as a health educator in New York and New Jersey when she began making abstract paintings and sculptures. Her return to the South in 1977 signaled a turn toward works in the landscape.

She fabricated three rock-like mounds in a marsh near Igbo Landing, where in 1803 a group of West Africans rebelled against their captors on a ship. Intended to look organic, the rocks are in fact made of concrete and coated with tabby, a local material made from oyster shells, sand, and water, which was used to build homes and memorials by Black communities in their newfound continent, pre and post liberation.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.