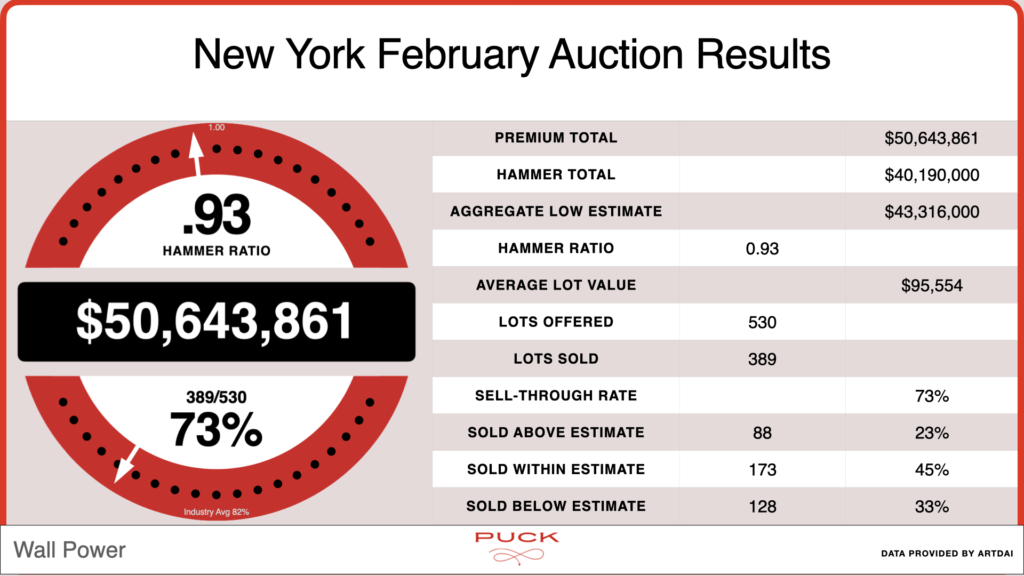

The art market has begun to heal. That’s the main takeaway from last week’s sales in New York, where $50.6 million worth of art works were sold for an average price of $95,000. In the end, 73 percent of the 530 lots offered were sold, with just under a quarter selling at prices above the estimate range. Meanwhile, about one-third had to be sold at compromise prices, where the consignor did not get bids to their estimates.

The hammer ratio for these sales, however, was a weak .93, which suggests the market still has a ways to go before gaining real momentum. (A hammer ratio above 1.00 is one sign of an advancing market.) Still, it’s worth pointing out that the low sell-through rate probably had a greater impact on the hammer ratio than overall weakness in bidding. There are still signs that sellers’ expectations are out of line with buyers’ interest—27 percent of lots failed to find a buyer (or the consignors would not lower their reserves), and a third of the sold lots went for prices below the estimate. In other words, consignors are overvaluing their property and need to lower their threshold for getting cash out of their art.

Before we get further into last week’s numbers, let’s look at how these top-line metrics compare to previous years. We’ll start with the average price. In 2022, the last boom year for the art market, the New York midseason sales had approximately the same number of artworks on offer, but the average price of a work sold was $132,000. In 2023, the average price for a work fell to $92,000; in 2024, it bottomed out at $71,500. (In 2023 and 2024, there were significantly more works of art available in these sales as consignors rushed in, hoping to cash out before the good times came to an end. Alas…) The return to a lower number of works offered, and a higher average price, is a good sign for the market. But there’s still a large gap between this year’s 73 percent sell-through rate and the 90 percent sell-through of 2022.

Top Heavy

The hammer ratio for these sales charted a similar trajectory. In 2022, the hammer ratio was a blazing hot 1.23; in 2023, it fell to 1.02; and then in 2024, it bottomed at an unsustainable .77. The .93 hammer ratio achieved last week is a big improvement over the previous year, but still less than ideal.

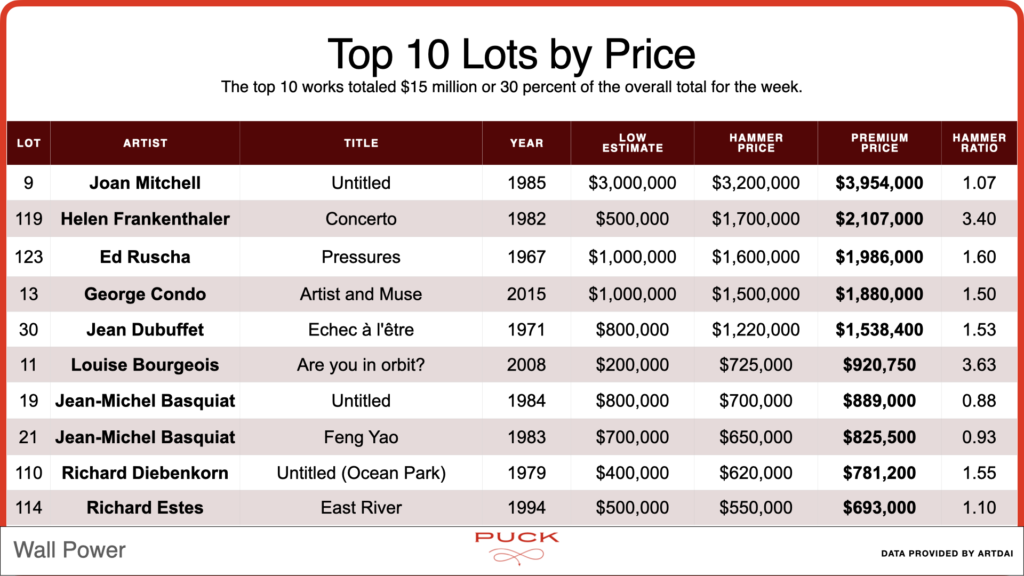

One final year-over-year comparison: If we look at the ratio of the value of the top 10 lots sold against the overall value of the sales, some other telltale signs emerge. When the value of the top 10 lots increases as a proportion of the overall sale value, it indicates concentrated bidding on a few works, as opposed to a broader-based interest. In 2022, the top 10 lots accounted for 25.5 percent of the value of the entire sales; in 2023, the proportion was the same; in 2024, it fell to 21 percent. This year, the top 10 lots comprised almost 31 percent of the value of the entire sales.

The sample size here is too small to extrapolate to the broader market. But, just in the context of these New York midseason winter sales, the higher proportion of value concentrated in fewer lots suggests buyers are ready to spend again for specific works by specific artists—in other words, an isolated willingness to spend. But I would not go so far as to call it market leadership.

Let’s look at those top 10 lots. The names are mostly well-established, historical artists: Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Jean Dubuffet, Louise Bourgeois, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Richard Diebenkorn. As I’ve noted here before, we’re well past the time in the cycle when we should be seeing more demand for historical work. The other names in the top 10 list are Richard Estes, George Condo, and Ed Ruscha, all living artists whose work is recognized as having a place in art history.

Of the 10 works at the top of the price scale, only the two Basquiats were sold below the estimates; three works (Estes, Condo, and Mitchell) were sold within the estimate range; and the remaining five works were all bid above their estimates. The Bourgeois and Frankenthaler works were subject to dynamic bidding that drove the hammer price to levels more than three times the estimate. The Bourgeois is the only work that appears on both lists of top 10 works: by price and by hammer ratio.

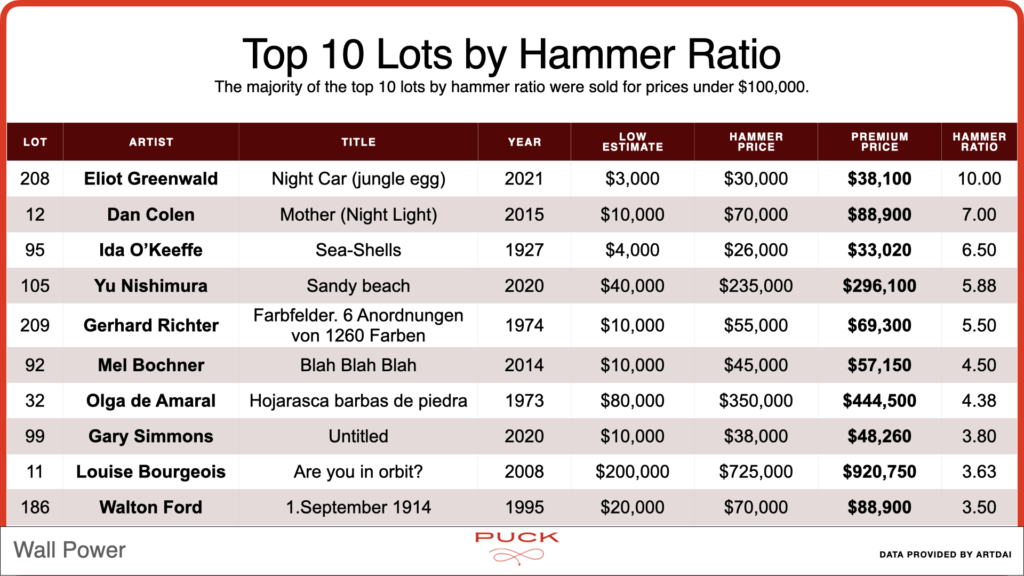

If we switch to the top 10 lots by hammer ratio—which should indicate the work that is sought after by collectors and advisors—we see mostly low-value pieces below $100,000. Yu Nishimura and Olga de Amaral join Bourgeois in seeing their work get bid up aggressively to six-figure sums. The De Amaral work achieved her fourth-highest price at auction (the auction record was set just last May), but $444,000 is in line with her prices over the last five years. The Nishimura was a record for the artist, more than doubling the previous high. But only a handful of his works have ever come to the auction block. When we see a higher proportion of the top 10 works by hammer ratio sell for prices in the six figures—quite a high price point for these sales—it will be an indicator of market momentum.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content