This article is part of the Artnet Intelligence Report, The Year Ahead 2025. Our analysis of the second half of the year’s market trends provides a data-driven overview of the current state of the art world, highlighting auction results and trends, and spotlights the evolving tastes in a turbulent market.

New Money, New Taste

Growing up in Los Angeles, Justine Freeman spent every day with her grandmother, the legendary arts patron Betty Freeman. Together, they went to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to see paintings by Abstract Expressionist masters like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. At her grandmother’s Beverly Hills home, Claes Oldenburg’s sculpture of an eraser towered over the backyard, while paintings by Sam Francis and Roy Lichtenstein were displayed to magnificent effect against black-velvet-lined walls. And, of course, there was David Hockney’s 1967 acrylic Beverly Hills Housewife, 12 feet wide by 6 feet high, capturing her grandmother in a long pink dress. 1

“I have my grandmother to thank for my art appreciation,” Freeman said. “She was very confident in herself and in her taste. She taught my sister and me how you can look but not touch and how artwork has meaning and you have to respect it.”

These lessons have stayed with Freeman, now in her 40s, long past her grandmother’s death, in 2009, and the subsequent auction of her trove at Christie’s. A collector in her own right, she hopes to pass her love of art to her children. Together with her husband, Benjamin Khakshour, Freeman has filled their cozy ranch-style home with ultra-contemporary paintings by many artists whose prices have skyrocketed in recent years, including Jadé Fadojutimi and Hilary Pecis.

Collectors Justine Freeman and Benjamin Khakshour pose with Jadé Fadojutimi’s Silhouette of My Memory (2021). Courtesy Justine Freeman and Benjamin Khakshour.

A new generation of art patrons is coming into its own, poised to reshape the art market. Millennials and Gen Zers accounted for a quarter to a third of bidders and buyers at the two major houses in 2024, more than doubling their share in five years. Unlike earlier

generations, which prized connoisseurship while amassing both new and historical work, the “next gen” is hyper-focused on the present.

In addition to buying emerging art, they are pushing up prices for nontraditional collectibles that were once unimaginable as marquee auction lots, such as sneakers, comic books, and Hermès bags. In this topsy-turvy new world, young artists often command higher prices than canonical ones. Last year, 15 artworks by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (born in 1977) generated $13 million at auction, while 13 pieces by the great Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) tallied $6.1 million, according to the Artnet Price Database.

Emblematic of where the new money is moving, Maurizio Cattelan’s controversial 2019 artwork Comedian—a banana taped to a wall—went for $6.2 million at Sotheby’s in November, where it was purchased by the 34-year-old Chinese crypto entrepreneur Justin Sun.2

Crypto entrepreneur Justin Sun enjoys the

$6.2 million banana he purchased at Sotheby’s. Photo by Peter Parks / AFP via Getty Images.

The art industry is paying close attention to what the youngsters covet because many of them will be very, very rich. Economists forecast that $84 trillion in assets will change hands over the next 20 years. Members of Gen X (born between 1965 and 1980) stand to inherit $30 trillion, millennials (1981–96) $27 trillion, and Gen Z (1997–2012) $11 trillion, according to Bank of America.3 Their values, taste, and investment decisions will help determine the next cohort of top artists—who’s in and who’s out, who will endure and who will not.

“The burden is on us to educate them,” said Christie’s CEO Bonnie Brennan. “We need to create moments that make them feel that these things are relevant to them, matter to them, interesting to them.”

Changing generational tastes have moved markets many times before. Take American art and decorative objects from the late colonial era through American Modernism, which lost their luster in recent years.

Those categories were all the rage around America’s bicentennial, in 1976, according to art advisor Peter Kloman, a former American-art expert at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. In 1979, The Icebergs, a long-lost 1861 masterpiece by American landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church, fetched $2.5 million at auction in New York.

Only two other paintings had ever sold for more, the New York Times reported: Titian’s The Death of Actaeon (1559–75), which went for $4 million in 1971, and Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja (ca. 1650), which made $5.5 million in 1970.4

The audience for American art and design “used to be old-generational New England collectors, who grew up appreciating it because their parents and grandparents collected Hudson River School paintings and American furniture,” Kloman said.

Church’s auction record had reached $8.2 million by 1989 ($21 million, adjusted for inflation), and none of his works has come close to breaking it,5 partly because major masterpieces have not come up and partly because the number of committed collectors of the category has declined, dealers said. Meanwhile, the taste of global wealthy elites has shifted to Modern, postwar, and contemporary art, with pieces by artists like Picasso and Warhol surpassing $100 million at auction.

What happens if taste shifts again is “a big, very fundamental, rather philosophical question,” an art advisor to billionaires told me. The truth is, that moment is already here.

“What 45-year-old today is sitting on the edge of his or her chair, desperate for the moment they’ll be able to buy Jasper Johns? It’s just not happening,” the advisor said.

“They are desperate to buy Basquiat. You don’t get the same social cachet, bragging rights—call it what you will—for buying de Kooning, or Jasper Johns, or Rauschenberg today.”

A lot of money is at stake. Consider that just the top 10 artists generated almost $2 billion at auction in 2024, according to the Artnet Price Database. Meanwhile, the top 10 ultra contemporary artists (born in 1974 or later) realized $90.9 million. Established markets need to be protected and new ones developed.

Which is why grooming younger buyers “is a major priority at Christie’s, and we’re focused on ways to further reach and engage that demographic,” said Brennan.

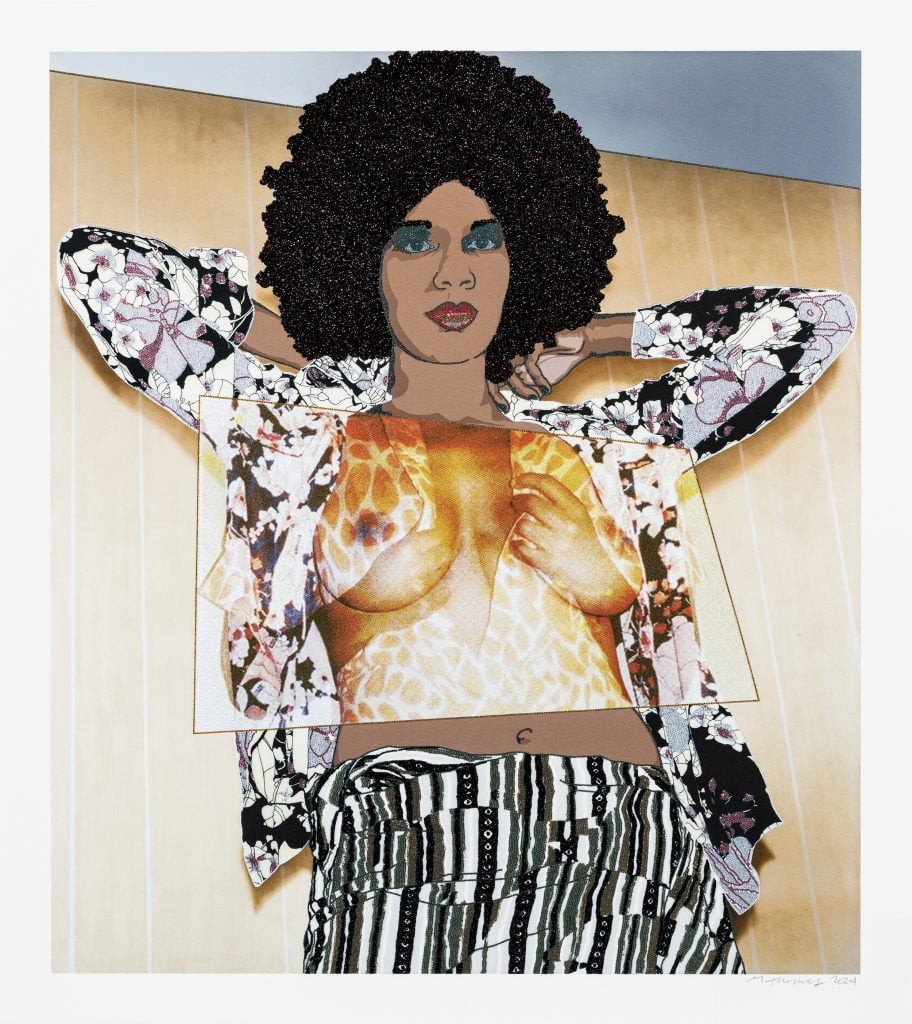

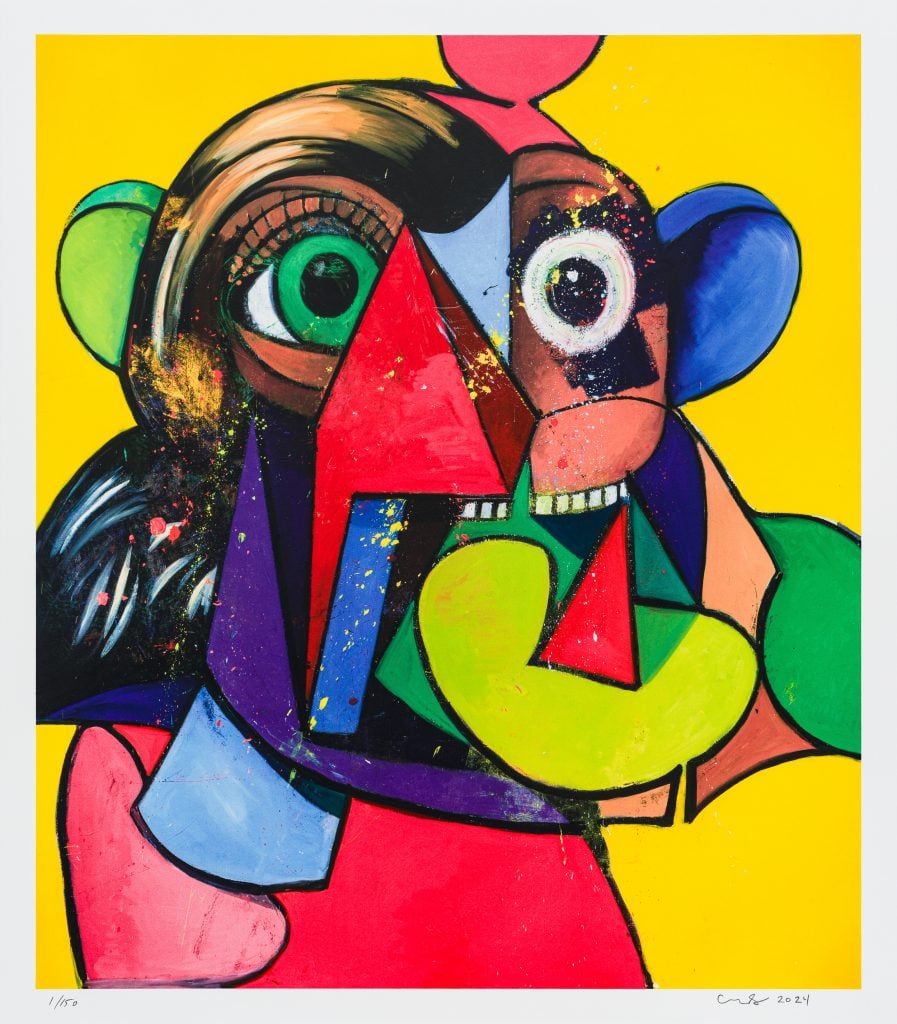

Avant Arte works with leading artists to make affordable, limited-edition prints that are targeted at new collectors. Mickalene Thomas’s Portrait of Maya #10 (2024) appears

at top, George Condo’s Portrait and Head (2024) at bottom. Courtesy of Avant Arte.

Some $222.5 million worth of Picassos sold at auction last year, the third-highest total for any artist. Imagine if young collectors decide to cancel Picasso because of how he treated women, or lose interest in Warhol (in fifth place, with $182.6 million in sales) because the famous figures he depicted mean nothing to them.

“Much more than Picassos and Warhols, and other modern greats, our audiences are motivated by living artists and supporting their output,” said Mazdak Sanii, co-founder and CEO of Avant Arte, an online platform based in Amsterdam and London that hawks affordable art.

The average price of the first acquisition is €640 (about $670), Sanii said. Avant Arte has produced limited-edition prints by Mickalene Thomas, George Condo, and Ai Weiwei. Many have sold out, including Condo’s Portrait and Head (edition of 150), which was priced at $6,438, generating almost $1 million in sales.sup>6

“As they gain more confidence and spend more time collecting, that price sensitivity changes,” Sanii said of his 30,000 clients. “They can go from $1,000 to $50,000 in just a few years.”

Do these budget buyers have the power to make markets? Probably not. Very often, a few superrich guys do that, after deciding an artist is ready to move into a higher price bracket. The multitudes follow, inflating prices and sometimes causing bubbles.

Writing about this very dynamic in Artnet Magazine in 2012, collector Mickey Cartin recounted his conversation with an art dealer who predicted that Basquiat would soon be seen as the next Van Gogh.7 “By that he must have meant that the $5 million-$25 million price range for the artist’s pictures will soon readjust to $50 million-$250 million,” Cartin wrote. A month earlier, a new Basquiat record, $16.3 million, had been set at Phillips de Pury; Van Gogh’s then record was $85.2 million.

At the time, “a handful of exceptionally wealthy people” were buying and selling Basquiat works from and to one another, Cartin wrote. “I guess that constitutes a market. If there is buying and selling, even if only five or ten people are involved, that is a market of sorts. I asked him directly what would happen when the very few rich people change their minds. He countered in a way that made me think. ‘They already have,’ he said, meaning that they’d decided to pay the higher prices for Basquiat.”

The dealer was right. Last year, Basquiat ranked fourth among all the artists tracked by the Artnet Price Database, with $183.4 million in annual auction sales, compared to Van Gogh’s $74 million. Basquiat’s auction record is $110.5 million; Van Gogh’s is $117.2 million.

What Sticks?

Galleries and auction houses are taking different approaches in their pursuit of the next generation of buyers. The auction houses are going after them aggressively. Many galleries are still making them prove they are worthy. (More on that later.)

The houses are throwing a lot of strategies against the wall to see what sticks.

Christie’s invited digital artist Volker Hermes to create prints inspired by the offerings in the auction house’s February Old Masters sale. Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

They promote luxury sales, though it remains to be seen how effective these are in converting clients to purchasing fine art. “It’s not like you buy a piece of jewelry or a handbag and you are an art collector,” an auction executive said, adding that customers who buy vintage cars are more likely to buy art.

They also tap influential figures from the worlds of fashion, design, sports, and social media to energize sleepy categories.

During its “Classic” week in New York, Christie’s organized a talk between one of its experts and digital artist Volker Hermes, who is known for altering Old Master paintings to make surreal and humorous photo collages. Hermes also created a series of works based specifically on Christie’s auction offerings, including paintings by Parmigianino, Lucas Cranach the Elder, and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.8

When Christie’s won philanthropist Jayne Wrightsman’s collection of decorative arts, in 2020, it brought in Aerin Lauder, the Gen X Estée Lauder heiress, to position 19th-century teacups and flower plates for a new generation.9

“I think it’s very important to live with beautiful things,” she says in the video Christie’s created, placing bouquets of roses on a table laid with a selection of china with a rose pattern. “It inspires you and creates a sense of whimsy and surprise in your everyday life. There’s something very important about embracing the past and having these pieces work in the present.”

Aerin Lauder. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd. 2025

Sotheby’s marshals a cadre of influencers through its “Contemporary Curated” sales, including supermodel Karlie Kloss and Grammy-winning former Destiny’s Child singer Kelly Rowland. Its latest curator is fashion entrepreneur Victoria Beckham, aka Posh Spice.10

Material that would have been eyebrow-raising on the auction block a decade ago is now sold routinely. Sotheby’s recent 12-lot “One” auction included Muhammad Ali’s shorts and Kobe Bryant’s sneakers alongside a Roman marble from the 1st century and a pair of Louis XV cabinets.

A set of six Air Jordan sneakers that Michael Jordan wore while clinching championships (in 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 1998). Sotheby’s sold the set, dubbed “The Dynasty Collection,” for $8.03 million in February

Christie’s tried appealing to the tech cohort with its “Gen One” auction in September of vintage computers from Paul Allen’s collection, which raked in $16 million.11

Dallas-based Heritage Auctions had a record year in 2024 with $1.9 billion in sales, led by a $32.5 million pair of Dorothy’s ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz (1939), a $24 million Babe Ruth jersey, and a $6 million Superman comic book.12

“These markets are real,” stated art advisor and collector Ralph DeLuca, who said he’s made millions in this segment. “They are more rooted in passion, connoisseurship, and nostalgia than just buying a Jadé Fadojutimi in the evening sale.”

Not Like Us

Lisa Dennison, Sotheby’s chairman of the Americas, who is known for working with top older clients, said she now also advises their children.

“Even if they admire and respect what their parents have created, they often can’t afford to keep the collections,” Dennison said, mentioning estate taxes and siblings’ competing interests as factors that can send storied collections to auction.

Many younger collectors want to put their own imprint on their elders’ collections.

“People will naturally migrate to the artists of their generation and have their own sense of discovery,” Dennison said. “I don’t see them saying, ‘I want to do what my parents did.’ ”

Loie Hollowell, Stacked Lingams in green, yellow and flesh (2018) in the home of Justine Freeman and Benjamin Khakshour. Courtesy Justine Freeman and Benjamin Khakshou.

Take Justine Freeman, the Los Angeles collector. She is focused on the female artists of her generation, an area her grandmother’s peers largely overlooked.

A vibrant abstract canvas by Fadojutimi has a prime spot in her and her husband’s house. A painting by Rachel Jones hangs in the couple’s bedroom. A Loie Hollowell glows above the fireplace. Freeman sees a conceptual link between the interiors painted by Pecis and the exteriors painted by Hockney. Her enormous Leslie Martinez reminds her of her grandmother’s Sam Francis.

Female artists were “a really big gap in my grandmother’s collection,” Freeman said. “Women didn’t have a platform before. Now that we do, it’s really important for us to focus on female art. It’s today’s world, and we try to stay avant-garde and look forward.”

New Locations

How would a profound change in taste impact the masterpiece market?

Even if younger Americans aren’t interested in their parents’ trophies, plenty of people globally “covet these great things,” said Dennison. “There’s a whole world out there that’s happy to lap up these masterpieces. I am not worried that great works of art will lose their value.”

Fernando Botero’s Society Woman (2003) which sold in February for $1.02 million at Sotheby’s first major auction in Saudi Arabia. Photo by Amal Alhasan/Getty Images for Sotheby’s.

In the early 2000s, Russia’s newly minted oligarchs and American hedge-fund managers entered the art market and sent prices for some Modern and postwar stars soaring. Qatar and China became major forces in the 2010s, with the private-museum boom driving demand for top works.

Other parts of the Middle East are poised to take off. The Louvre Abu Dhabi is building its collection from the ground up, and Dubai’s art scene is growing. Saudi Arabia is constructing scores of museums and ramping up commissions for AlUla by contemporary giants like James Turrell and Agnes Denes.13

Galleries and auction houses have been expanding into new territory. Sotheby’s has conducted pop-up auctions in locations beyond its dedicated salerooms in art capitals like New York, London, Paris, and Hong Kong, bringing the party to people’s backyards. Its 2021 auction in Las Vegas of Picassos from the MGM Resorts collection generated about $110 million.14 In February, Sotheby’s did its first pop-up auction in Saudi Arabia, offering art by Warhol and Condo, NBA jerseys, Patek Philippe watches, and Birkin bags.15 More than 30 percent of participants were under the age of 40, according to Sotheby’s.

A signed jersey that Michael Jordan wore during the 1998 NBA

playoffs, which Sotheby’s sold for $840,000 last November. Photo by Amal Alhasan/Getty Images for Sotheby’s.

That cross-category approach appeals to younger buyers, according to auction specialists. “It’s something I see all the time,” Sotheby’s vice chairman of private sales, Jackie Wachter, said.

“People want to take their money and put it into beautiful art, beautiful watches, beautiful jewels, beautiful handbags.”

One of her young clients, who works in the fashion industry, recently bought a Cy Twombly, an African mask, and a cool watch, Wachter said. A young couple collects ultra-contemporary art alongside Art Deco and ancient Chinese porcelain. In October, she bid on their behalf on three Henry Moore busts, winning two, at Sotheby’s auction in Paris.16 “They are creating an aesthetic,” she said.

Entry Point

Starting to collect art on the primary market is not easy. Art is expensive. The art world often seems inaccessible to new entrants, who have to jump through all kinds of hoops to prove their bona fides to galleries.

Advisor Nazy Nazhand remembers how, in 2014, soon after joining Lehmann Maupin gallery, she presented the idea of cultivating a new generation of art lovers coming into the market. She had worked with clients from the Gulf states and with nontraditional collecting backgrounds. They didn’t follow the unwritten rules of collecting “the same 20 artists or supporting the same 20 institutions,” Nazhand said.

Her pitch didn’t land, she said.

“They were dismissive at best,” Nazhand said about the gallery. “They thought that these collectors weren’t worthy of their attention. But it wasn’t just them. Everyone thought that. How do we claim to be a global industry but refuse to accept people who are different?”

Rachel Lehmann, co-owner of the gallery, said that Lehmann Maupin had adapted its “strategies significantly over the last decade to reach a digitally native audience.” In the past five years, it has started selling prints by its artists and hosted a variety of events for potential younger clients.

When Freeman and Khakshour began collecting, a decade ago, they experienced “flat-out rejection” from galleries when they inquired about works they liked, Khakshour said. Freeman said she felt weird having to drop her grandmother’s name to prove that they belonged in the club.

“It’s like applying for a job,” she said. “You need to send a long email to a gallery describing why you are worthy of an artwork.”

Eventually, they began working with an art advisor, Adam Green, who opened doors and helped the couple buy coveted works by hot artists, sometimes gaining access by agreeing to donate another work by the same artist to an institution.

Given the idiosyncrasies of the industry, their friends have a hard time understanding the couple’s passion for art collecting.

“They think we are crazy,” Khakshour said. “Most people are like, ‘Why aren’t you investing in real estate?’ ”

Endnotes

1. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5204545

3. https://www.ml.com/articles/great-wealth-transfer-impact.html

5. On the list of Church’s top auction prices, the number-two and -three slots belong to pictures that went for about $4.73 million and $4.19 million way back in 1999 and 2000, respectively. Artnet Price Database.

6. https://avantarte.com/artists/george-condo

7. http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/news/artmarketwatch/art-market-doomsday-5-5-12.asp

10. https://www.sothebys.com/en/digital-catalogues/a-curation-of-contemporary-art-by-victoria-beckham

12. https://dallasexpress.com/city/heritage-auctions-breaks-sales-records-in-2024/

13. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/james-turrell-commission-show-saudi-arabia-alula-2600489

15. https://www.cnn.com/2025/02/10/style/sothebys-saudi-arabia-origins-tan/index.html

16. https://news.artnet.com/market/art-basel-paris-report-art-detective-2554590

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content