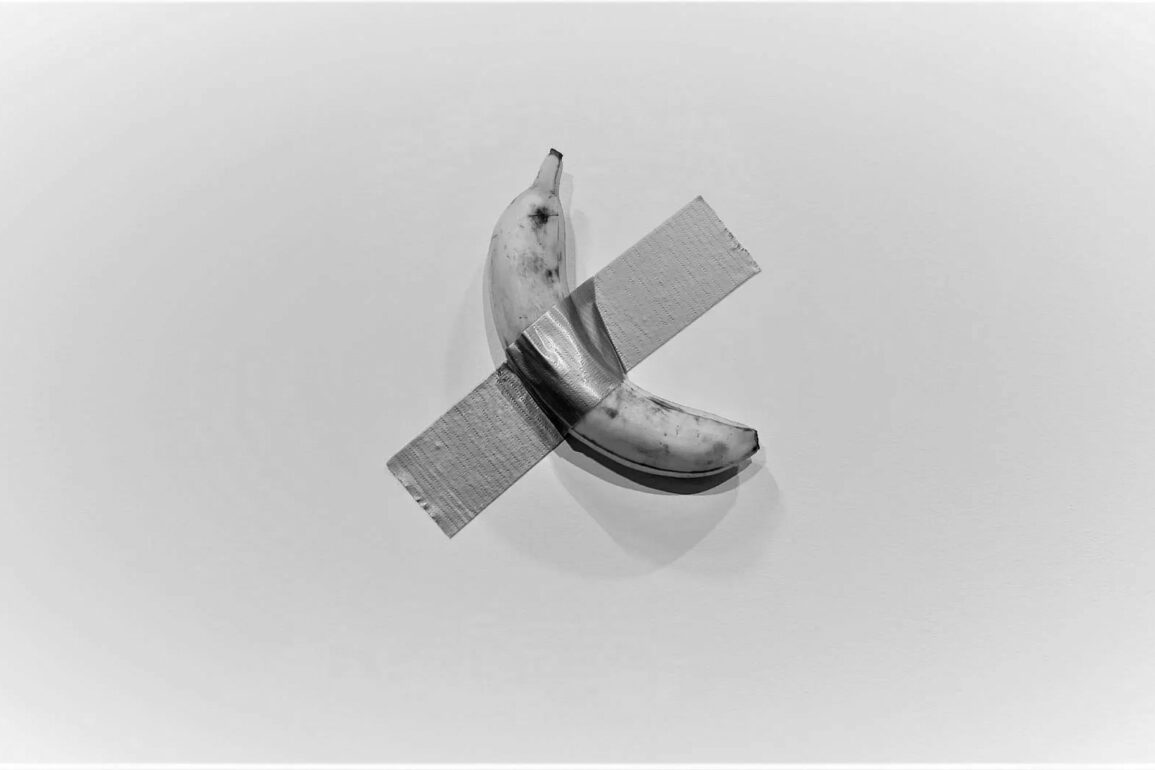

One achievement of the avant-garde has been to show that anything can be art. There are numerous memorable examples spanning the century from Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) to Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (2019), a banana duct-taped to a wall, sold at Sotheby’s for $6.2 million in November 2024. But the fact that the readymade and other forms of deskilled art have become an accepted form of artistic practice should not detract from their enduring and intriguing novelty. It is difficult to think of other social forms where the same latitude prevails, where anything may count as a token within the practice in question. Gift-giving might be one example. You can make a gift of anything, and the fact that it is a gift will probably enhance its value for the recipient. But it doesn’t add value to the object for anyone else, let alone economic value. At least until the development of crypto, which seems to have managed a similar feat, art has seemed unique in this respect. And this raises a question: why is there the amount of art that there is? How can a social practice in which value can be extracted virtually from thin air succeed? On the other hand, why, given that art can be anything, isn’t there a lot more of it?

Traditional aesthetic theories proved insufficiently elastic to account for the possibility that anything could become art. In contrast, institutional theories of art suggested that although anything, or almost anything, might be art, it could become so only in relationship to an artworld. The concept of the artworld was developed by Arthur Danto to explain how it was that something could be art while being identical to something which was not. His answer was that ‘the difference . . . is a certain theory of art. It is the theory that takes it up into the world of art, and keeps it from collapsing into the real object which it is’.footnote1

This account implied that all that was required to turn an everyday object into a work of art was a conducive ‘conceptual atmosphere’ and that it is participation in this ‘discourse of reasons’ that ‘defines the artworld’.footnote2 George Dickie’s version of the theory placed greater emphasis on the actual social networks—artists, gallerists, curators, critics, auction houses, museums, academic institutions—that collectively make something into art (in Dickie’s terms, ‘confer the status of a candidate for appreciation’) within a given society.footnote3 In a world where anything can become art, but not everything is art, the institutional theory is probably the most serviceable in that it is not easily disproved. There is nothing that is generally considered to be art that the institutional theory cannot account for, and there is nothing that is not art that could not be re-appraised.

On the other hand, the institutional theory explains very little. Not only does it fail to specify the criteria by which qualitative judgements are made, but it ignores the quantitative dimension altogether. If the artworld is able to make art out of anything, then there would appear to be clear incentives, whatever the criteria invoked, to maximize the quantity of art. Not only is art often considered, especially by those involved in the artworld, to be an intrinsic good, but having more art would mean that the artworld could expand as well, and, given that art objects are often worth more than their non-art equivalents, that there was an economic basis for this growth. The artworld has indeed expanded enormously, and there are now museums of contemporary art in many cities of the world, but it has, nevertheless, not expanded as much as it might have done, given the theoretically limitless potential for growth.

Noting that the price of Warhol’s plywood Brillo boxes was 2×10footnote3 that of their real-life counterparts, Danto rhetorically asks: ‘Is this man a kind of Midas, turning whatever he touches into the gold of pure art?’footnote4 On his account the answer is no, it is not Warhol who is Midas but the artworld. And while it is not necessarily the case that everything that becomes art has aesthetic value, nor that everything with aesthetic value has economic value, the artworld is designed to effect the transformation. However, although anything can be art, and art can have almost any economic value, it is not the case that anything can be made to have any value by becoming art. Auction houses are not full of readymades selling for millions of pounds. On the contrary, they are so rare as to generate headlines whenever they occur. If the institutional theory of art is to maintain plausibility, then it needs to explain why the artworld, unlike Midas, has exercised an uncommon degree of self-restraint, or else why its Midas touch is so unreliable.

Values

Institutional theories of art have no evaluative principles of their own, but rather point towards other theories to explain the underlying logic of the artworld in determining what art is and what counts as good art. To what extent can these other theories be of help? Theories of modernism usually work off a conjunction of two things: the existence of some sort of value, convention or tradition and the negation, critique or calling into question of that value or institution by the modernist or avant-garde artist. Variants include classical modernism in which advanced art in any field negates the specific tradition or medium from which it comes, and the neo-avant-garde in which the artist questions not the medium but the institution of art itself.footnote5

This is recognizably the framework within which Sotheby’s presented Cattelan’s Comedian. Encouraged by Cattelan himself, who is quoted as saying that ‘To me, Comedian was not a joke; it was a sincere commentary and a reflection on what we value’, Sotheby’s presented the work as something to be valued for its interrogation of value: ‘Comedian’s theoretical origins can thus be traced back to the Duchampian readymade, the genesis of a larger ontological schism which decentred craft, rarity and technical mastery in favour of the conceptual value assigned by the artist.’ In this account, the banana represents ‘the apex of a hundred-year-long, intellectual yet irreverent interrogation of contemporary art’s conceptual limits’ which includes Manzoni, González-Torres and Koons, as well as Duchamp. ‘Evoking and advancing the strategies of his predecessors with sardonic and subversive wit’, Cattelan is said to have prompted the world ‘to reconsider how we define art, and the value we seek in it’.footnote6

The assumption here is that art operates within an economy of value, and that something becomes a candidate for positive evaluation as art precisely insofar as it questions the artistic values of the past. However, the negation of value does not usually lead to its proliferation: in other cultural spheres (e.g., religion), sustained critique has led to the attenuation of the practice in question. Negation-driven theories of modernism therefore have the opposite limitation to the institutional theory of art in that they are unable to explain why the artworld should have expanded at all.

A more promising approach is offered by Boris Groys, who neatly synthesizes the institutional theory of art with theories of modernism in his account of the artworld as the ‘socially codified manifestation of the fundamental equality between all visual forms, objects and media’. On this view ‘all images are already acknowledged as being of equal value’, and so the artworld favours ‘anything that establishes or maintains the balance of power’. Every thesis must have its antithesis, so rather than simply negating or erasing what preceded it, a good artwork is one that addresses an existing imbalance or exclusion, ‘affirming the formal equality of all images under the conditions of their factual inequality’.footnote7

One merit of this account is that, unlike theories based solely on negation, it offers an explanation for the expansion of the institutions of art themselves. According to Groys, it is the museum rather than the theory of art that prevents the readymade from collapsing back into real life, for the less an art object differs from its everyday equivalents the more the difference depends on context. So the logic of equal aesthetic rights, which requires whatever is neglected to be upgraded, leads directly to ‘the building-up of museums’, in order to secure the difference institutionally.footnote8

But in that case, why does the ratio of readymades et al. to museums remain puzzlingly low? Following Groys’s argument, it would seem that in order to maintain the ‘balance of power’ the museum should contain as many bananas as there are still-life paintings. But in fact, Cattelan’s Comedian is one of an edition of three. This is not atypical. Even the most successful readymades are available only in very small editions. Duchamp said that he soon realized the danger of repeating himself and decided to limit their production. Not only did he make few readymades overall, but when he recreated his early ones with Galleria Schwarz in the early Sixties, they were produced in editions of eight.

The original problem remains. Anything can be art, and yet everything has not become art, and the artworld, which effects the transformation, has expanded, though rather less than it might have done if all the claims made for it were warranted. Indeed, the Midas touch has been used so sparingly that we might begin to wonder whether it exists at all. The assumption that the artworld can simply ascribe artistic value to almost anything, even if only as the negation of some existing value, seems to be demonstrably true (what is Cattelan’s banana, if not the latest proof?) but nevertheless devoid of explanatory power. Perhaps another approach is needed.

Uncertainty

In Dada, a somewhat different emphasis is already discernible: a concern with chance and uncertainty, combined with a marked interest in the model of financial services as a hedge against risk.footnote9 Tristan Tzara might proclaim ‘Dada doute de tout. Dada est tatou. Tout est dada. Méfiez-vous de dada.’footnote10 But as Hans Richter put it at the eighth Dada gathering, Dada is also ‘the soul’s means of defence against the unpredictable’.footnote11 In Raoul Hausmann’s words: ‘Dada is the only savings bank that pays interest for eternity . . . When the twilight of the gods dawned, the only survivor was Dada. Put your money in Dada.’footnote12

This heightened appreciation of the role of the unpredictable was not just a response to the horrors of the First World War; it had a direct parallel in the economic theory of the time. Frank Knight’s Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (originally a dissertation submitted for an essay prize in 1917) identified lack of certainty as the central problem of economics:

It is a world of change in which we live, and a world of uncertainty. We live only by knowing something about the future; while the problems of life . . . arise from the fact that we know so little . . . The essence of the situation is action according to opinion, of greater or less foundation and value, neither entire ignorance nor complete and perfect information, but partial knowledge.footnote13

At the same time, Knight made a novel distinction between risk, which is quantifiable and susceptible to measurement, and true uncertainty, which is completely unquantifiable. Since risks are calculable, Knight argued, competition will tend to eliminate profit by narrowing margins, with the result that profit is dependent on the continued existence of uncertainty: ‘Profit arises out of the inherent, absolute unpredictability of things, out of the sheer brute fact that the results of human activity cannot be anticipated and then only in so far as even a probability calculation in regard to them is impossible and meaningless.’footnote14

It is worth considering the exhibition to which Duchamp submitted the urinal in this context. The First Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, which opened in New York on 10 April 1917, was an unusual event. Recognizing that ‘the great need is for an exhibition . . . where artists of all schools can exhibit together—certain that whatever they send will be hung and that all will have an equal opportunity’, the organizers set out to be completely, indiscriminately inclusive. There was no jury and the cost of submitting a work was modest. There were to be no prizes, and all artists were to be placed ‘on an equal footing before the public’. The exhibition contained works by 1,200 artists presented in alphabetical order by the surname of the creator (the starting letter was chosen by lot), ‘thus relieving the hanging committee of the difficulties raised by their personal judgements as to the merits of the exhibits’ and ‘freeing the individual exhibit from the control of merely personal judgements which are inevitably the basis of any system of grouping’.footnote15

Although not presented explicitly in these terms, the Society of Independent Artists embodied many of the features Knight considered to be prerequisites for perfect competition: ‘no exercise of constraint over any individual by any other individual or society’; ‘everyone makes something independently of everyone else’; ‘everyone has the same information’; ‘goods [are] homogeneous’, a ‘complete absence of physical obstacles . . . [making] exchange of commodities virtually instantaneous and costless’.footnote16 An exhibition set up on these lines will certainly ensure that the market for the works exhibited tends towards perfect competition. And, Knight argued, as a market approaches perfect competition there will be a corresponding tendency toward the elimination of profit.

What the Society of Independent Artists assumed they knew, but what, in fact, they did not and could not know, was what a work of art actually was and all the ways it might be produced. Duchamp exploited this unacknowledged area of uncertainty, and his urinal was rejected. It was assumed, without question, that whatever they might be, all the products in the market would be works of art produced by the craft skills of individual artists. But what if an acceptable substitute for a work of art produced in this way were a mass-produced item? The very inclusiveness of the Society of Independent Artists would then be in question, revealed either to be a sham or self-defeating and meaningless. Duchamp’s urinal introduced uncertainty into a market approximating to perfect competition through the absence of values.

In Groys’s view, the artworld affirms the equal aesthetic value of all things and strives to achieve a perfect balance between them by incorporating neglected objects, like the urinal, to restore the equilibrium. Knight offers an alternative account, which seems rather more plausible in light of the reception Fountain received: when the market tends towards perfect competition and the reduction of profit, the possibility of profit may appear to depend upon the introduction of uncertainty to disrupt the equilibrium.

Trust

Knight emphasized that uncertainty was the ultimate source of profit, but he also recognized that the presence of uncertainty changed the nature of business activity. ‘With uncertainty absent, man’s energies are devoted altogether to doing things . . . With uncertainty present, doing things, the actual execution of activity, becomes in a real sense a secondary part of life; the primary problem or function is deciding what to do and how to do it’.footnote17 In this context, Duchamp intuited, the artist ceases to be a maker and becomes an entrepreneur, exploiting the buyer’s uncertainty about the quality of the product to make a profit.

But there is a potential problem here as well: quality uncertainty. As George Akerlof pointed out, if sellers attempt to profit excessively from buyers’ uncertainty about the value and quality of the product, they may end up destroying the market from which they stand to gain. However, there are ways of counteracting the effect of quality uncertainty. Anything that creates trust between buyers and sellers: the brand name, the approval of a regulatory authority, or a recommendation from a consumer organization will allay some of the uncertainty.footnote18

Take the example of Cattelan’s banana. Nobody is likely to hand over a million dollars to an artist in exchange for a banana bought for 35¢ just like that, because the artist might easily change their mind about whether it was really a work of art, or how many other bananas they might go on to sell or give away. But they might pay $120,000, the price at which Cattelan’s bananas were originally sold in 2019, to a trusted dealer at Art Basel Miami Beach. One of the bananas was then gifted to the Guggenheim Museum, thereby confirming its status as an artwork of museum quality. When another of the bananas came back to the market it therefore did so with an accumulation of artworld intermediaries behind it (the dealer, the art fair, the museum, and the auction house itself, plus the buzz of media attention around the initial sale and donation).

In this context, the institutional theory of art potentially takes on a different valence; the artworld here functions not as an institution that confers status or determines value, deciding that this urinal or banana is of value as a work of art whereas others are not, but as a trusted intermediary offering some reassurance that the uncertainty involved in treating an everyday object as a precious work of art has a plausible context within which the risk involved might be worth taking, however unlikely that might seem. The artworld plays the role not of a value creator but of a risk manager: not someone who says this is good, but someone who says this is a good bet.

Selling the work for $6.2 million completes the cycle, confirming that the artist, the dealer, the museum and the auction house can be trusted after all. The sale does not confirm trust in the product itself in the sense that it does not make it easier for other artists to sell bananas in the same way, or even for the same artist to sell other bananas or pieces of fruit at a similar price. In this narrative, the function of the $6.2 million banana is not to establish the value of bananas or other readymades, but to establish trust in the system. It does not demonstrate the value of bananas as art so much as the ability of trust intermediaries to regulate the sale of bananas as art.

Trust architecture

Although it is widely acknowledged that ‘trust is at the heart of a well-functioning art market’, the type of trust involved is rarely discussed.footnote19 It is possible to distinguish between peer-to-peer trust between counterparties, intermediary trust (where counterparties trust the intermediary but not necessarily each other), and trust in which there is no intermediary but rather an accepted framework for enforceable dispute resolution.footnote20 In this context it is clear that the artworld relies heavily on intermediary trust but is unusual in that it is both the producer of quality uncertainty and the trusted intermediary needed to manage it. On the one hand, it threatens to burn down the museums, or else fill them with readymades; on the other, it provides the branding and networks of trust needed to prevent that from happening.

The artworld is, however, not unique in this respect. Niklas Luhmann argued that for some systems ‘it is precisely in their internal relationships that substantial injections of distrust are needed for them to remain alert and capable of innovation, so as not to fall back into their customary pedestrian ways of relying on one another’.footnote21 In such cases, as Diego Gambetta has pointed out, the trust provider ‘himself has an interest in regulated injections of distrust into the market to increase the demand for the product he sells—that is, protection. If agents could trust each other independently of his intervention he would . . . be idle. The income he receives and the power he enjoys are the benefits to him of distrust’.footnote22 In this context, Tristan Tzara’s warning ‘Do not trust Dada’, and Hausmann’s injunction to ‘Put your money in Dada’ are more compatible than they might appear.footnote23

If the contemporary artworld functions as a network for the generation and distribution of trust—the trust that is needed to allay the distrust created by the avant-garde’s exploitation of uncertainty—then the institutional theory of art is perhaps better construed in terms of trust than value. On this account, the artworld is not assigning value to individual urinals and bananas but rather using them to generate the distrust required to justify the artworld’s role as a trust intermediary. In which case, the revaluation of readymades is a function of the artworld’s trust architecture, rather than an exercise of its Midas touch. This suggests a different type of answer to the question of why there isn’t more art than there is, for the question is not why the artworld does not create more value, but why cannot it generate more trust? One hypothesis might be that there is a delicate balance between too little trust, which suppresses demand, and too much, which undermines the unique role of the supplier.footnote24 The size of the artworld may therefore be determined by this balance. One way to explore this hypothesis is to consider whether, if the trust architecture of the artworld were modified, the amount of art might be different as well.

Crypto

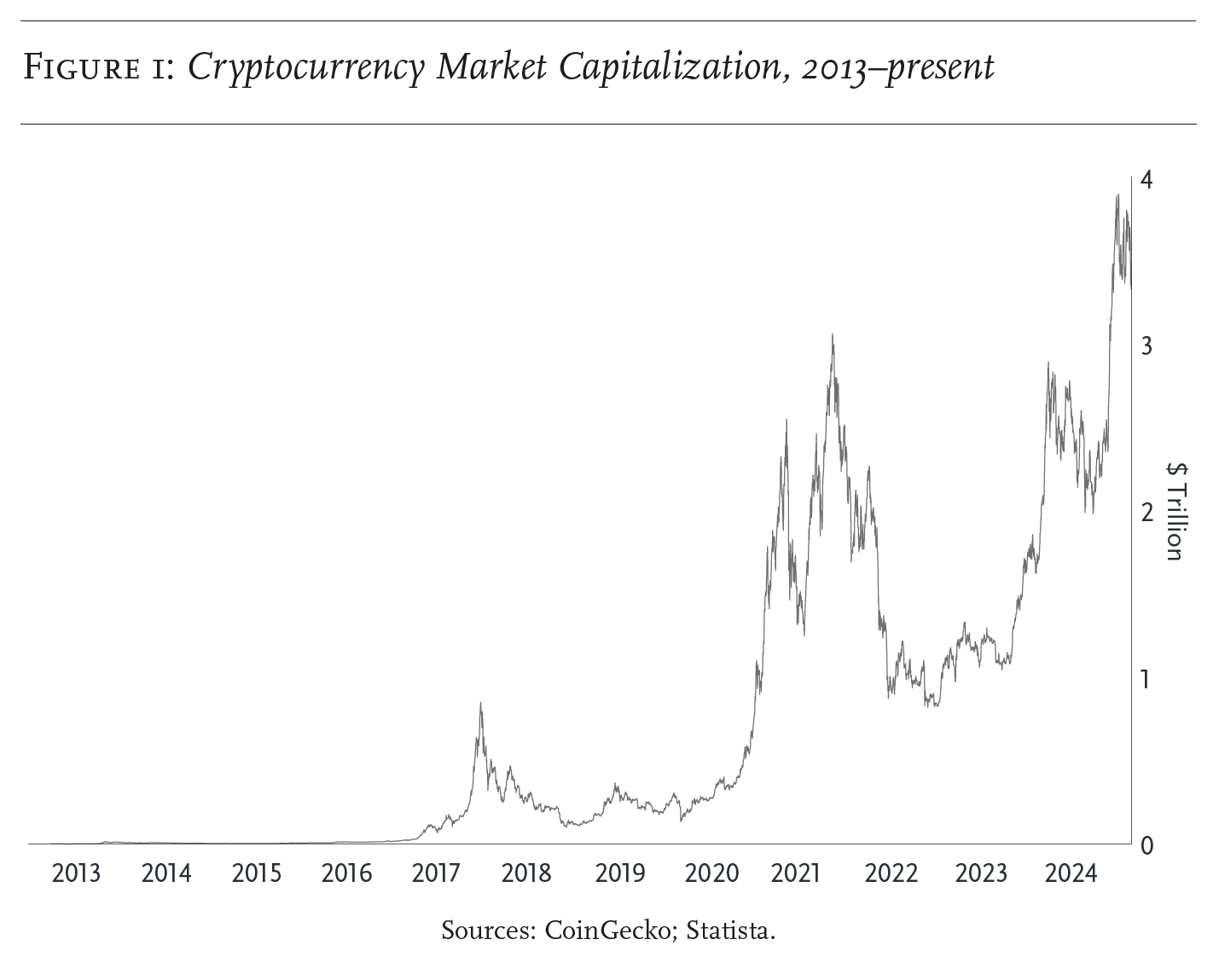

According to some estimates, the value of all the art in the world is about $3.3 trillion.footnote25 That is clearly a very rough estimate, but it provides a sense of scale: although it is only about 1 per cent of the value of all the real estate in the world, it is a bit more than the highest market capitalization for all the cryptocurrencies. The latter comparison is of particular interest, however, because crypto, like art, is something that can seemingly be created out of nothing. Indeed, the comparison is often made. According to its enthusiasts, Bitcoin, the original cryptocurrency, ‘is the greatest work of conceptual art of the 21st century’ and ‘Satoshi Nakamoto—the anonymous founder(s) of Bitcoin—is the Duchamp of the digital age’.footnote26

However, if crypto has roughly the same market cap as art, then Nakamoto has been a lot more successful than Duchamp. Whereas the discovery that art can be anything is a century old, Bitcoin, a digital currency traded online using cryptographic algorithms, was only invented in 2008. Despite losing half its value in the crypto winter of 2022, Bitcoin has proved relatively resilient and still accounts for more than fifty per cent of the value of all cryptocurrency. Why has Bitcoin been so much more successful than other cryptocurrencies and its artistic predecessors?

The invention of Bitcoin was presented as a response to the loss of trust in financial institutions after the crash of 2008. Nakamoto recognized this as the central problem to be addressed: ‘What is needed is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party.’footnote27 So whereas art relies on trust intermediaries, crypto tries to build systemic trust in a situation where distrust is assumed to be universal.

Although Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer network made up of people who have downloaded the free software, it does not work on the basis of peer-to-peer trust. Participants in the network are anonymous and no one has any reason to trust anyone else. As for the currency itself, it is nothing but the record of the transactions that are made using that network. Trust in the system of recording transactions is therefore paramount, and this is achieved using a distributed ledger, the blockchain, which ensures that each transaction is accompanied by the immutable record of all previous transactions. Transactions are added to the chain through mining, which involves hashing (coding) the new and archived transactions together with an arbitrary number and adding the new block to the existing chain.footnote28 As an incentive to participate in mining, winners are rewarded in Bitcoin, which is the only way new Bitcoin is minted. New Bitcoins are created though the verification process itself, building trust in the algorithm.

Kevin Werbach calls this trustless trust, a form of trust in which ‘nothing is assumed to be trustworthy except the output of the network itself’ and there is no connection between institutional actors and the system: ‘To accept a cryptocurrency transaction as valid is to trust the network it is based on, without necessarily trusting any individual participant or higher authority.’footnote29 In crypto, no periodic injection of distrust is required because no trust is ever assumed, and the anonymous decentralized system creates no opportunities for building trust in anything other than the algorithm itself.footnote30

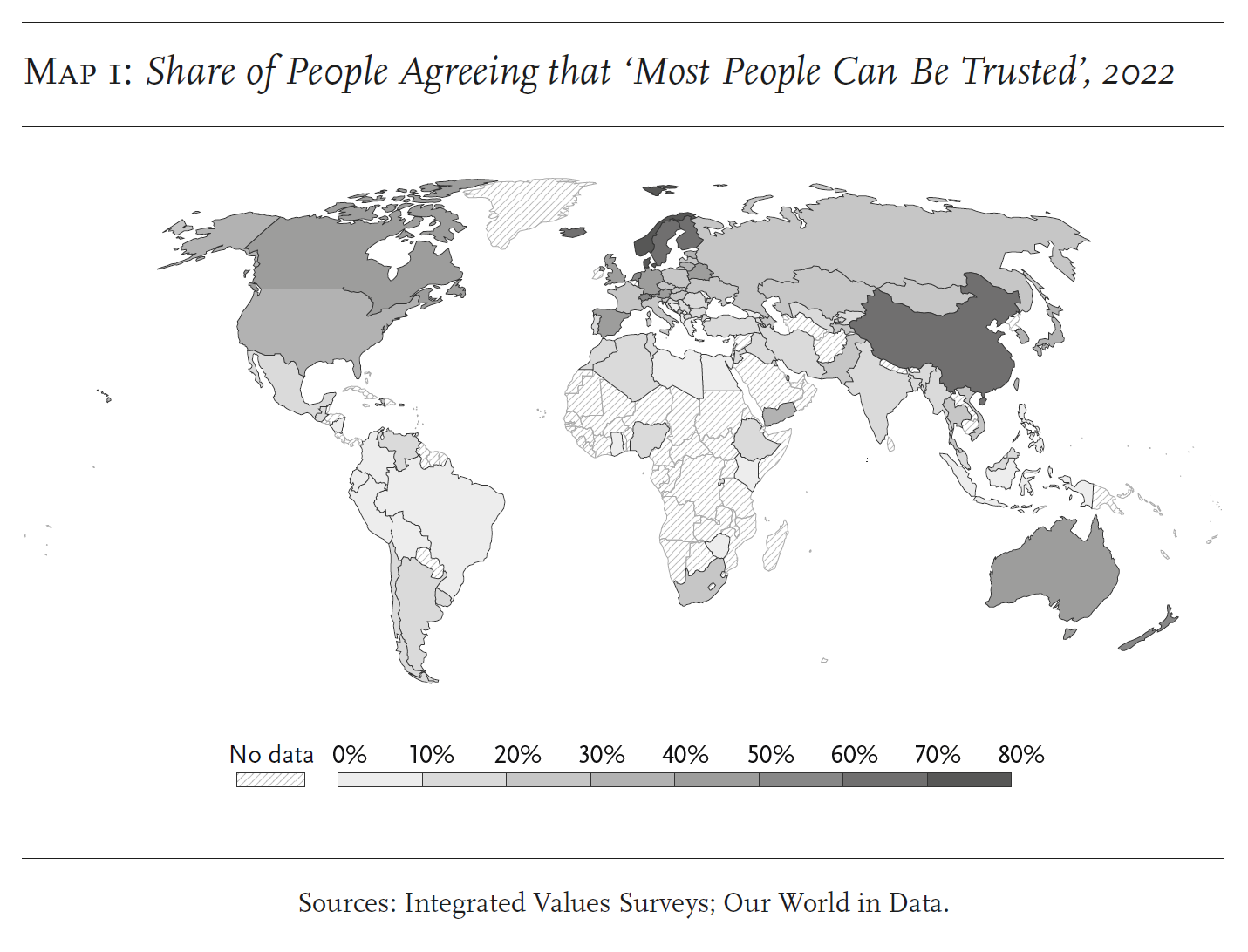

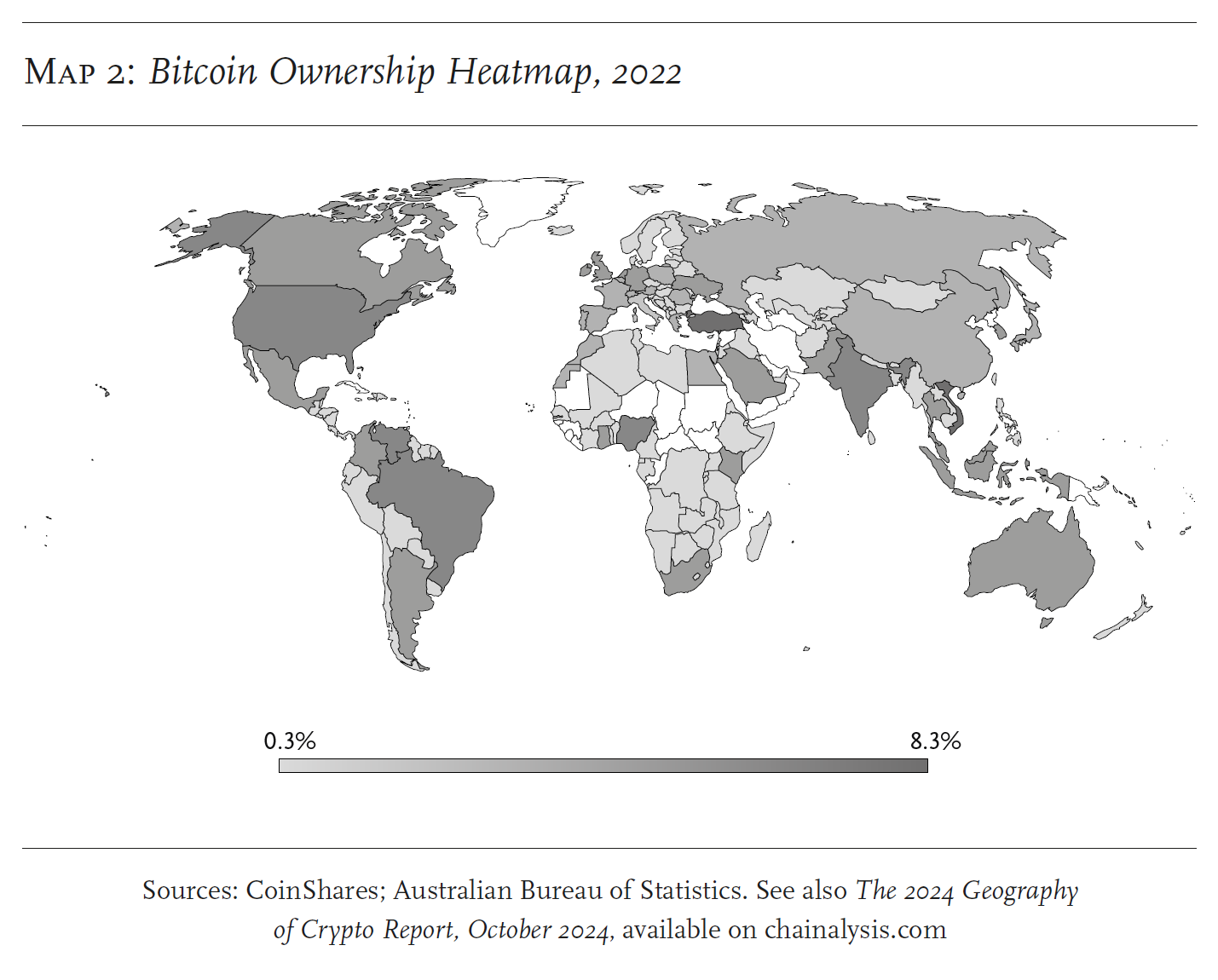

The novel trust architecture devised by Nakamoto has given Bitcoin a distinctive global profile. Not only has it been spectacularly successful, but it has a particular appeal in countries where trust in people and institutions is low (see Map 1, below). Unlike art, which sells in societies that have high levels of trust, crypto prospers in low-trust societies where fear of fraud, the confiscation of property, and currency devaluation are high (see Map 2, below). Bitcoin therefore seems to be far less dependent on the wider trust environment that appears to be necessary for both the art market and the stock market to flourish.footnote31

What accounts for this divergence? Some key features of Bitcoin’s trust architecture have artworld parallels: the blockchain is a form of authentication and provenance, and Bitcoin also artificially restricts access to creative opportunity through proof of work (mining).footnote32 (Other currencies, such as Ether, the coin of the Ethereum blockchain, prefer proof of stake, i.e., holdings in the currency used as collateral.) The most obvious difference is the artworld’s reliance on intermediary trust. Not only is intermediary trust localized, but transaction costs are high because all the intermediaries are taking a cut. Intermediaries are also potentially capricious; if their tastes change, your work can easily be undone, because it is easier to rewrite the history of art than it is to rewrite the blockchain.

The other key difference is limited quantity. The Bitcoin algorithm has fixed the total supply of currency at 21 million Bitcoin, with the rewards for mining new Bitcoin diminishing asymptotically over time. In contrast, one reason there may not be more art is that the amount of art is potentially limitless; increasing supply could ultimately devalue existing art (both aesthetically and economically), making the artworld very cautious in its expansion.

NFTs

Crypto was originally intended to be a form of currency, not art. But its success has suggested ways in which art might break out of its institutional straitjacket by working with trustless rather than intermediary trust. Non-Fungible Tokens are digital certificates of ownership verified on a blockchain, usually Ethereum rather than Bitcoin. Art-related nfts are simply digital images that come with a certificate of ownership attached.footnote33 The benefits of using blockchain technology to sell digital art are essentially the same as those of cryptocurrency more generally. The technology cuts out intermediaries while providing a high level of security with regard to the purchase, provenance and authenticity of the work. According to The

nft

Handbook, that means ‘No uncertainty, no “experts” and no hocus pocus’.footnote34 Anyone can make nfts and then sell them directly to the end user, with the advantage for the artist that, while the technology does not prevent their work from being copied, it does prevent it from being faked, since each token is verifiably unique.

In 2021, nfts hit the art market. Beeple, a previously unknown digital artist, sold Everydays: The First 5,000 Days, a collage of the daily images he had been making, for $69.3 million at Christie’s in New York, the third highest price ever paid for an artwork by a living artist (behind Koons and Hockney, and roughly what you might expect to pay for a major work by Titian). However, this sale was an exceptional one in every way. Most creators prefer not to sell their works bundled together but individually, as a series of unique numbered nfts in which the same character or algorithm is used repeatedly, but the final form is slightly different.

Within this category there is a broad division between Generative Art, such as Chromie Squiggle (2020), in which an algorithm randomly generates an abstract digital image in line with the artist’s or purchaser’s instructions, and Profile Pictures (pfps, which can be used online as an avatar and sometimes carry other benefits such as membership of online communities), which use digitally manipulated imagery derived from comics and video games, so that each token is unique but nevertheless part of a line which gives it a distinct brand identity. Of these, the CryptoPunks, 10,000 algorithmically generated pfps created by Larva Labs and originally given away for free, have been the most successful, with individual exemplars of the rare ‘alien’ type regularly selling for over $10 million. Even ordinary Punks still change hands for over $100,000, making the market cap for the line as a whole $1–2 billion.

The world of art-related nfts is quite unlike the artworld generally in that creators of nfts are often pseudonymous and have little or no training in fine art. nfts are simply minted and dropped into the market with no attempt to accrue cultural prestige along the way. The Sotheby’s catalogue entry for a sale of Bored Apes in 2022 gives a taste of the environment within which they are marketed. No theoretical labour has been expended:

Born out of crypto culture, they [the Bored Apes] spearheaded the member’s club and digital collectibles trends as more and more people grew affectionate to these apes and what they represent. For this reason, we see them as so much more than just an ape, they are art . . . Coming from collector and notable ape holder Prepstothepros, this online auction will mark [the] first time that Apes #8331, #7724, #1598, and #7610 have been made available since they were minted 18 months ago. Ape #8636 was minted by the well known collector Pranksy, at which point it exchanged hands and was collected by the present owner. Prepstothepros minted over 100 Bored Apes, and has continued to hold one of the most significant collections to date, including the #1 ranked Ape based on rarity.footnote35

On the face of it, it would appear that nfts had solved the problem the artworld could never resolve, the almost limitless production and sale of art with minimal marketing, transaction and storage costs. Warhol provided the model for making reproductions of popular imagery in expensive limited editions. But the new technology means that whereas Warhol would usually only sell an edition of 150 or 250 silkscreen prints, it is quite possible to sell 10,000 unique nfts of the same line at an equivalent price.

One factor is that nfts can be traded online with very low transaction costs on platforms like Open Sea. Transaction volumes are high, with about 0.4 per cent of a line being traded every 24 hours (which would equate to the entire line being bought and sold at least once a year)—akin to the turnover ratio on stocks. In contrast, transaction costs in the artworld are prohibitively high, and turnover painfully slow, with some suspicion attached to works that are obviously being flipped. While sales have slumped over the past two years, there were 19,000 nft sales a day in 2022 (down from a peak of 225,000 per day in 2021), compared with 123,000 annually in contemporary art auctions.footnote36

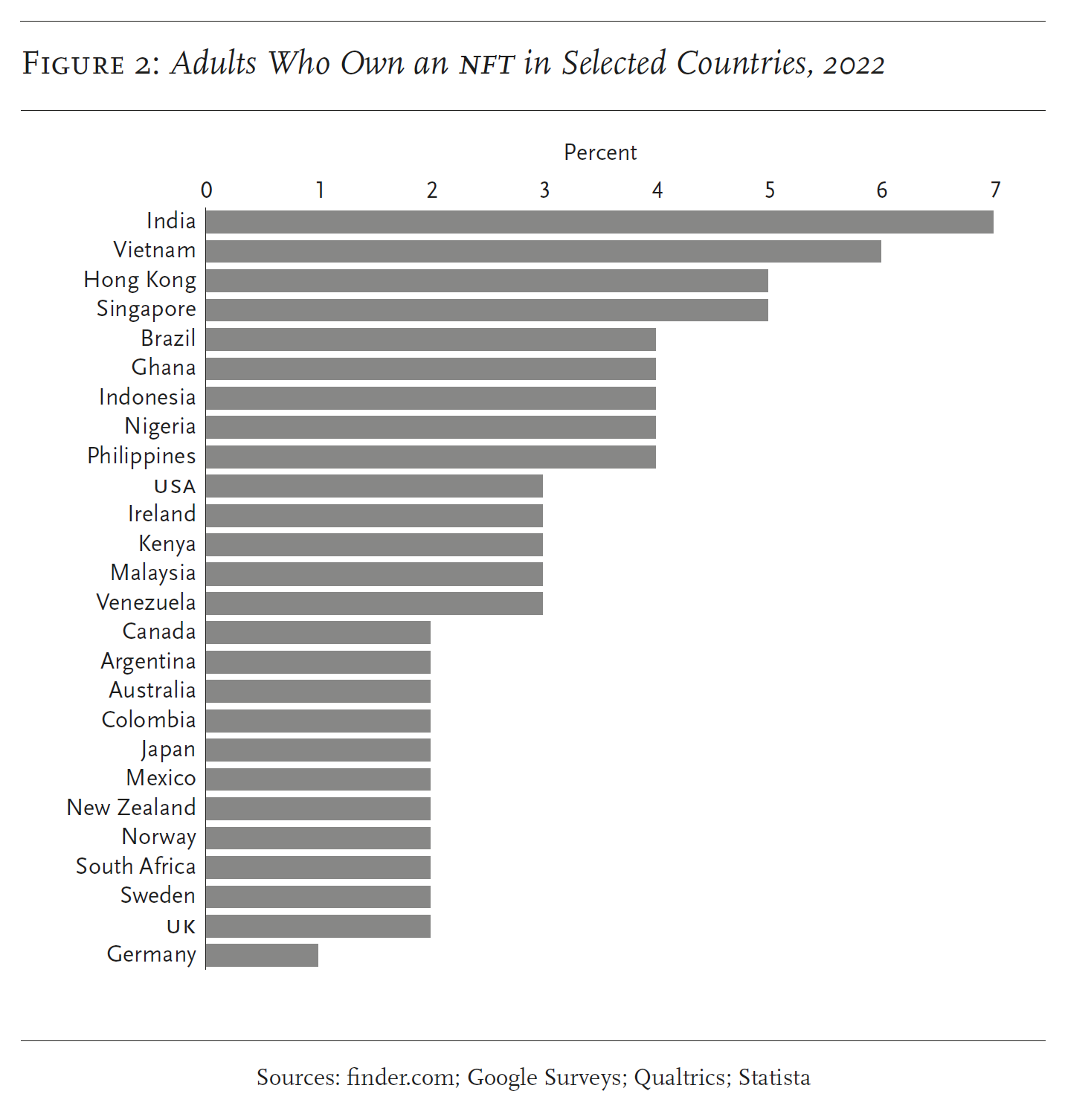

nfts have also reached a far wider market that is markedly different geographically, and in terms of age and income levels. Like other crypto products, nfts flourish at the periphery rather than in the capitalist core—the inverse of the contemporary artworld. This obviously leads to the suspicion that what is being traded is not digital art per se, but rather securities with jpegs attached—thus the sec has investigated Bored Ape Yacht Club for selling unregistered securities. Many in the non-commercial artworld see it this way too. David Joselit, for example, argues that ‘the nft has arrived to reverse Duchamp’s gesture . . . Duchamp used the category of art to liberate materiality from commodifiable form; the nft deploys the category of art to extract private property from freely available information.’footnote37 Jonathan Jones claims that ‘they are just simian poker chips that celebrate the thrill of the market. A purer form of capitalism has never existed.’footnote38

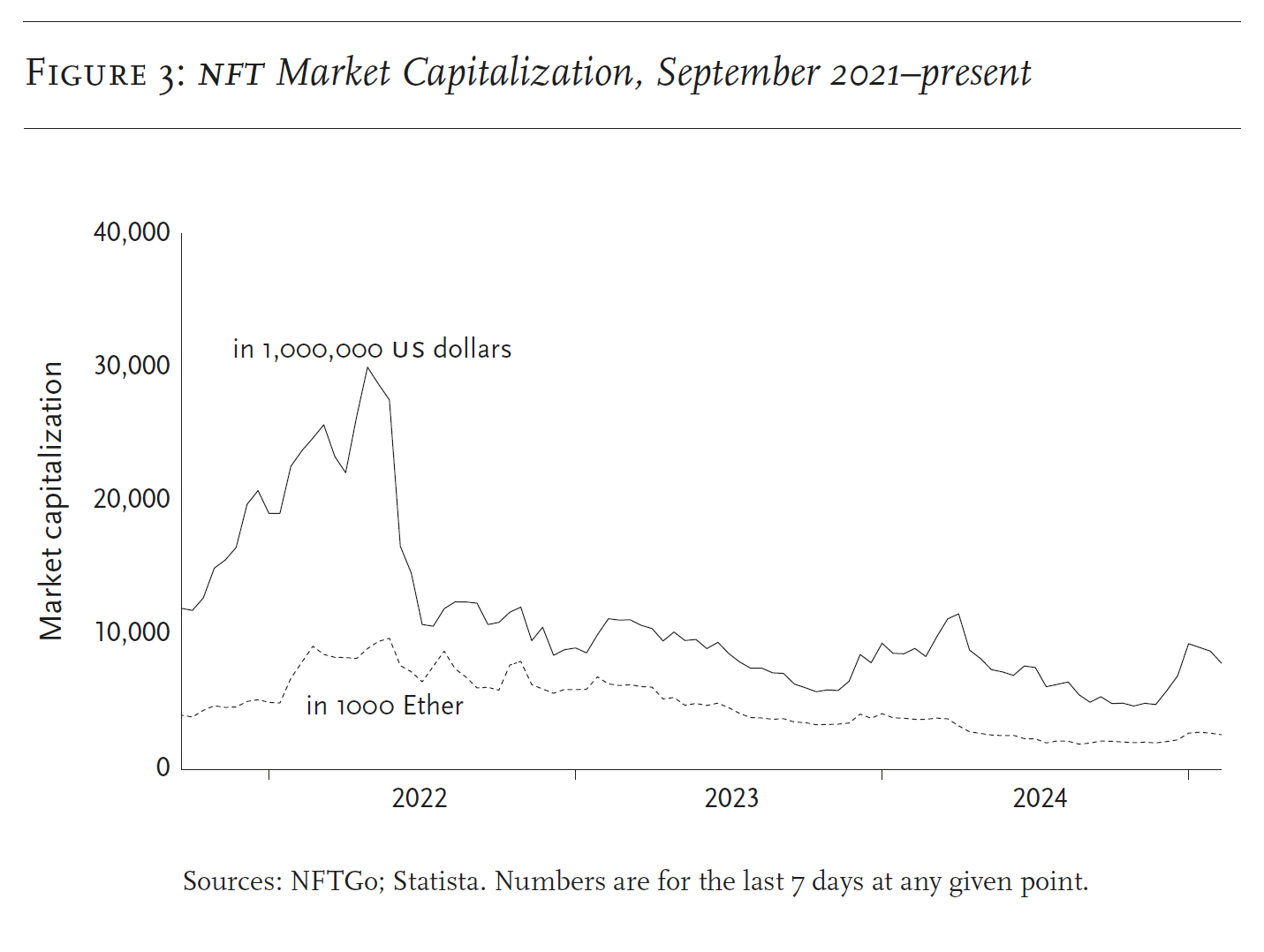

However, although they can be traded like securities, nfts are not in themselves anything other than bits of code, and they have proved far less resilient than crypto currencies since the market crash of early 2022. A 2023 report by DappGambl suggested that Total nft market cap was around $20 billion, about 5 per cent of what it was in 2022: ‘Of the 73,257 nft collections we identified, an eye-watering 69,795 of them have a market cap of 0 Ether (eth).’ There was ‘a significant imbalance between the creation of new nfts and the actual demand for these digital assets in the current market landscape’: about 95 per cent of nfts are now considered dead, only 0.2 per cent of 2024 nfts profitable. Astonishingly, less than 1 per cent of these nfts boast a price tag over $6,000, indicating the rarity of high-value assets even within the cream of the crop.footnote39

Despite its phenomenal early success, the market for nfts has quickly begun to show some of the same symptoms as the traditional art market: chronic overproduction, massive unsold inventory, and poor returns on all but a fraction of products. In 2024, the Artprice Contemporary Index tracked 205,000 artworks by artists born after 1945 at auction worldwide, of which 132,000 sold, 57 per cent for under $1,000 and 82 per cent for under $5,000.footnote40 However, this data skims off the top of the market, including the work of only 33,000 artists globally, a minuscule fraction, given that the number of people claiming to be artists is 2.67 million in the us alone. Were artworks to be assessed by the same criteria as nfts, it is likely that almost all would be considered dead.footnote41

Rather than mirroring the resurgence of Bitcoin and some other cryptocurrencies, nfts seem to be slumping into the pattern of art because they have adopted only parts of Nakamoto’s trust architecture. In particular, the nft market may have misjudged the relative importance of the blockchain (which functions in the same way for both Bitcoin and nfts) and the mining process. Unlike Bitcoin, which has a limit internal to the algorithm and a mining process that demands proof of work, unlimited nfts can be minted (a much easier technical process), without either proof of work or stake, so the market quickly becomes flooded. By 2023 it was already apparent to some observers that ‘as a consequence of the high speed and the relative lack of curatorial control over artwork publishing [i.e., nft minting], a significant current challenge for crypto artists is “artwork hyperinflation” . . . or “over-tokenization”’.footnote42

The ambiguous fate of nfts illustrates the sensitivity of the product to the trust architecture of the market. Both art and crypto may rely on trust, but unlike crypto, which creates trust in an ocean of distrust, the artworld relies on trust intermediaries and generates just enough mistrust to demonstrate the continuing need for them. The size of the artworld is determined by this dynamic—poised between creating too much mistrust, thus undermining the demand for art, and creating so much security that there is no further need for an artworld at all. Rather than being as resilient as Bitcoin, nfts have become increasingly unsuccessful because they are very much like art in their potential for limitless overproduction, but without the benefit of the structures of intermediary trust that allow the art market to function smoothly, albeit on a more limited scale.

One way to remedy this situation would be to introduce curators and other trust intermediaries into the nft market. Some commentators note that ‘potential investors are becoming more discerning, carefully evaluating the style, uniqueness and potential value of nfts before making a purchase’, with the result that smaller lines, curated collections, provenance, gifts to museums and so on are becoming more important.footnote43 Others have suggested that ‘a possible step forward could be to propose curated experiences, provided either directly by third parties and processes or using Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (daos) and Token-Curated Registries (tcrs)’.footnote44 If this sounds like a return to the artworld, then nfts are perhaps sufficiently like art to require the same trust architecture after all.

Bananas again

As if to illustrate the point, the purchaser of Cattelan’s Comedian was Justin Sun, the Singaporean founder of the cryptocurrency Tron, and the vendor of a line of Bored Ape nfts known as Bored Ape Yacht Club Tron. According to Sun, Comedian ‘represents a cultural phenomenon that bridges the worlds of art, memes and the cryptocurrency community’.footnote45 What this means in practice is that Tron, with an unsold inventory of thousands of unminted Mutant Apes, will use Sun’s highly publicized purchase of the banana as part of a rebrand. Having launched the Tron Bored Apes with the purchase (possibly from himself) of a Bored Ape for the equivalent of $15 million, Sun is now using the same strategy with Cattelan’s banana as Tron moves towards a banana-based rebrand ‘with a signature design that truly represents Ape community’.footnote46

Purchasing Comedian may be an overt attempt to import the trust architecture of the artworld into the world of nfts, but it is important to note that the banana is now meant to function in precisely the opposite way. If the banana originally served as an injection of distrust into the art market, demonstrating the need for trust intermediaries, it is seemingly intended to function as an injection of trust into the nft market that will potentially justify the minting of thousands of nft bananas.footnote47 It is unclear whether this will work.footnote48

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content