Ken Kiff was a brilliant odd one out in post-second world war British painting. In works that sing with colour and texture, he crafted wibbly-wobbly fables in which eyes and noses slide around faces, animals tower over mountains and dreaming, desiring, questing men are rendered poignantly goofy. Looking to modernist greats such as Klee and Miró, Kiff made colour a defining principle, mixing abstraction with recurring symbols culled from a private mythology that included birds, salamanders, mountains, water, goddess-like women and the “Little Man”, a diminutive chap with a bendy body vulnerable as plasticine, who walks a lonely path. His was a bombast-free take on life’s agony and ecstasy, as idiosyncratic as it is relatable and human.

When Kiff died aged 65 in 2001, his reputation was that of a bygone artist’s artist, whose heartfelt dedication to his medium and the creative process was far removed from the arch, brash conceptual output of the then-dominant YBAs. Now, though, appreciation of his prolifically produced, personal work is growing afresh. “He speaks to a younger generation, partly in terms of his mix of abstraction and figuration,” says Ella-Rose Harrison, the director of Hales Gallery, where a new exhibition looks back to his 18 months from 1992 to 1993 as “associate artist” in residence at London’s National Gallery. “There’s also a different engagement with his themes,” she adds, “bringing the mythical into the everyday, or psychologically charged space.”

Kiff was the second artist the National Gallery invited to respond to its art historical giants and it was a prestigious gig. Paula Rego was the first and Kiff was followed by Peter Blake. Yet he had reservations. “He wasn’t pro-institutions,” says Kiff’s daughter, Anna. “He was acutely aware it was a very masculine environment. He was from a working-class background and it wasn’t his comfort zone.” For an artist who gloried in colour, the National Gallery’s collection was also very brown.

Working on site in a basement studio with his huge collection of cassettes playing everything from baroque harpsichord to jazz, Kiff went in search of what he called “the essence” of paintings. He didn’t make many sketches there, but rather “looked intensely at paintings over and over and over”, Anna explains. What drew him to work by artists including Rubens, Van Gogh, Rembrandt, Pisanello or Giovanni di Paolo is always fresh and surprising. He had a particular thing for Rubens’ trees. He paid attention to art’s physicality, be it the wood something was painted on or a touch of gold pigment. A splash of colour from a muddy Renaissance landscape might inspire the dominant element in his own work.

At times, his paintings adhere closely to the originals, adapting themes and figures that chimed with his own mythologies. John the Baptist, the hunter Saint Eustace or the hermit Saint Jerome might be loftier cousins of Kiff’s lonely traveller. At others, his paintings seem to upend the assumptions of the past, as with Woman Watching a Murder, inspired by Bellini’s brutal all-male scene The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr. Kiff takes the blue from a scrap of sky in Bellini’s otherwise washed-out woodland setting to create an azure vision, where a tiny tussling couple are watched by a giant woman, sad and resigned.

Kiff later wrote that he approached the National Gallery project as he did all his work, as “many interlocking thoughts” which were visual not verbal. “A painting doesn’t become a painting because it conforms to rules of what a painting should be,” he continued, “but because the ‘thought’ or ‘understanding’ has happened.”

Ken Kiff: The National Gallery Project is at Hales Gallery, London, to 24 May

Driven to abstraction: five works from the exhibition

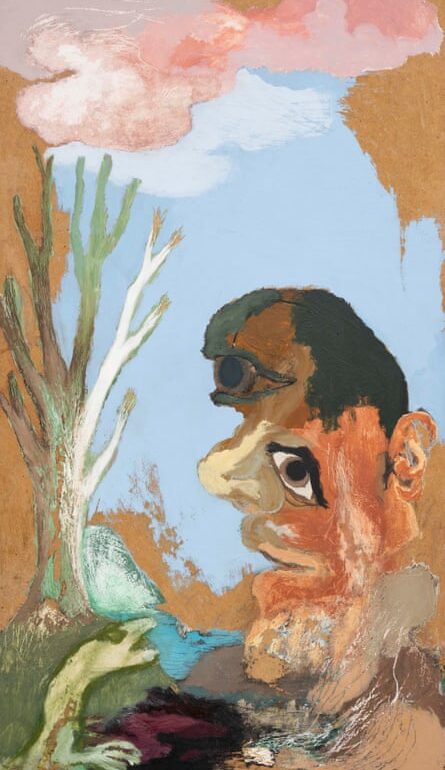

White Tree, Large Face, 1990-1996

Kiff has left the hardboard he painted on visible here. Anna recalls that he found it in keeping with “the quality of darkness, the browns you find in a lot of old master painting”. The tree was inspired by Rubens but the face – literally falling apart – belongs to the modern world.

Woman Watching a Murder, 1996 (pictured at top of article)

This meditation in blue shows how Kiff used colour as a structuring principle, with its echoing forms and aqua shades. It also underlines his interest in the bleed between representation and abstraction, with the inky midnight morass in the background suggesting a cave or intangible dark thoughts.

after newsletter promotion

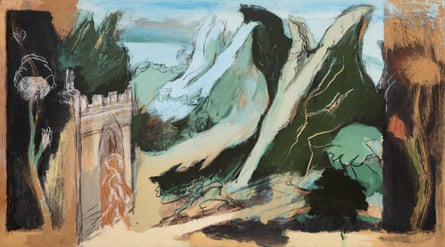

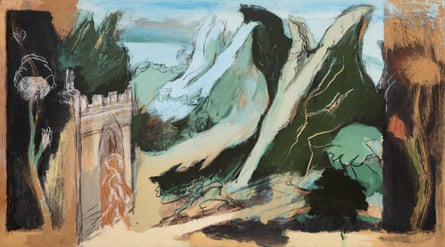

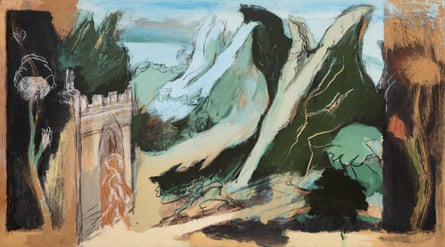

After Giovanni di Paolo, 1992-1993

This is one of Kiff’s paintings that sticks closely to its source inspiration, Giovanni di Paolo’s Saint John the Baptist Retiring to the Desert. Its elements are close to those he was already exploring in his work, from the giant flowers or huge mountains dwarfing the isolated traveller to jarring shifts in scale.

Master of St Giles, 1994

In addition to paintings, Kiff also produced prints inspired by his time at the National Gallery, such as this woodcut teeming with earthy life that looked to works by an anonymous 16th-century artist known for depicting Saint Giles’s friendship with a deer. “This print encompasses so many things he found important,” says Anna, “including our relationship to the environment.”

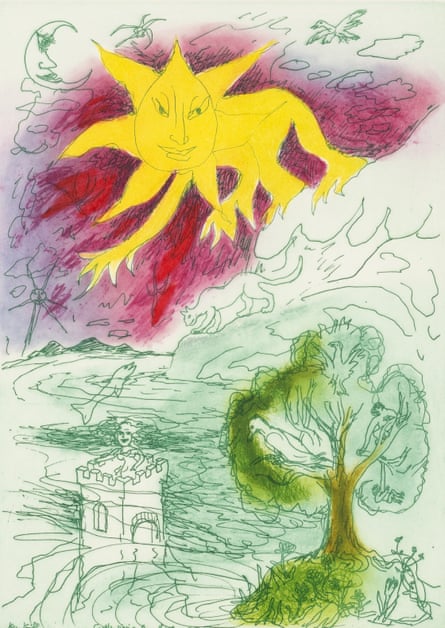

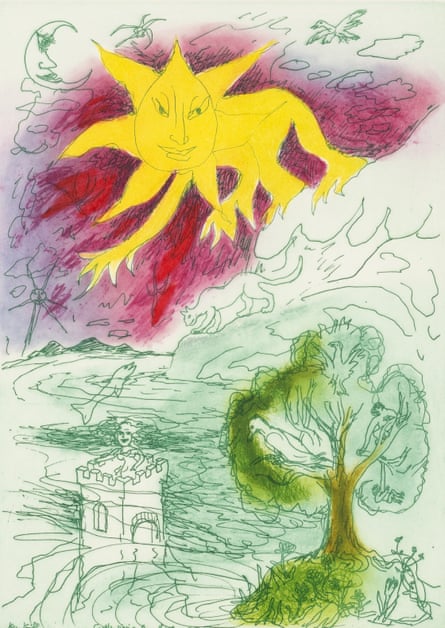

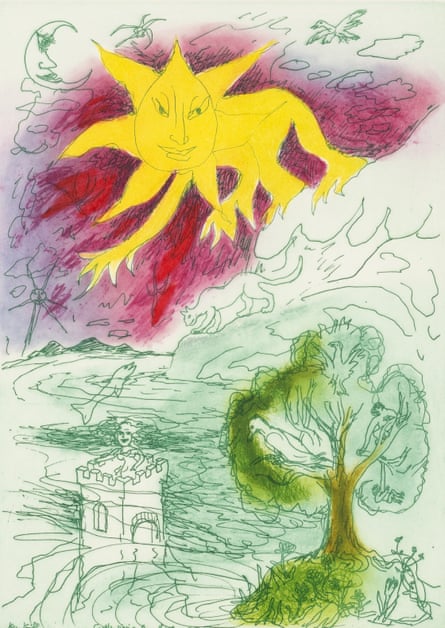

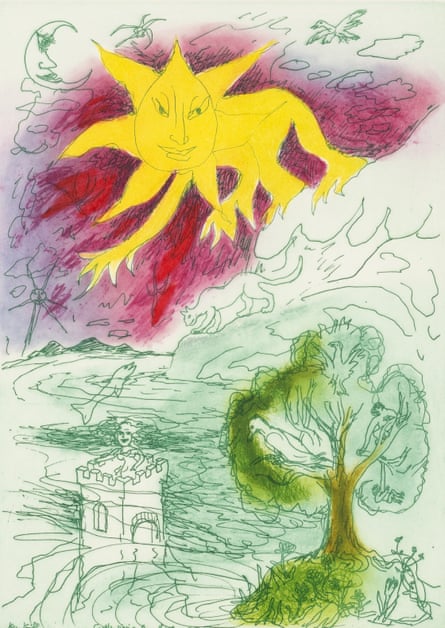

Castle Rising from the Sea, 1993

This etching showcases Kiff’s renowned vivid palette, and speaks to the creative process, with its castle born from the waters of the sea. The sun is a recurring symbol in his work with connotations of enlightenment or inspiration. This one’s no Apollo, though; it crawls along recalling one of Kiff’s other favourite tropes: the salamander.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content