Bryan Rindfuss

Salvadorian artist Lorena Molina (center) hired cumbia band Chulada to perform at the opening of her garden-like Artpace exhibition “Cuando el Regreso es la Cosecha (When the Return Is the Harvest).”

Twice a year, Artpace’s International Artist-in-Residence program invites a trio of artists — one from Texas, one from elsewhere in the U.S. and one from abroad — to live and work in San Antonio for a period of two months.

Supported by a $6,000 stipend and a production budget of up to $10,000, the resident artists are encouraged to experiment freely while creating new projects befitting what late Artpace founder Linda Pace dubbed her “laboratory of dreams.” All selected by guest curators, these artists might have little in common — and the site-specific exhibitions they create might be devoid of connective threads.

However, when synergism does occur, the takeaways become more resonant and holistic — as is the case with the recently unveiled exhibitions created by Laura Veles Drey (Houston), Anita Fields (Stillwater, Oklahoma) and Lorena Molina (San Francisco, California via El Salvador).

During an opening reception and artists’ talk held on March 20, New Hampshire-based guest curator Jami Powell highlighted some of the parallel themes trickling through Drey’s “Nothing Grows in a Straight Line,” Fields’ “Where the Light Shines Through” and Molina’s “Cuando el Regreso es la Cosecha (When the Return Is the Harvest)” — exhibition titles that could easily double as chapters of the same book.

For starters, there’s an abundance of greenery throughout — which runs the gamut from implied vegetation to actual plants growing in the galleries.

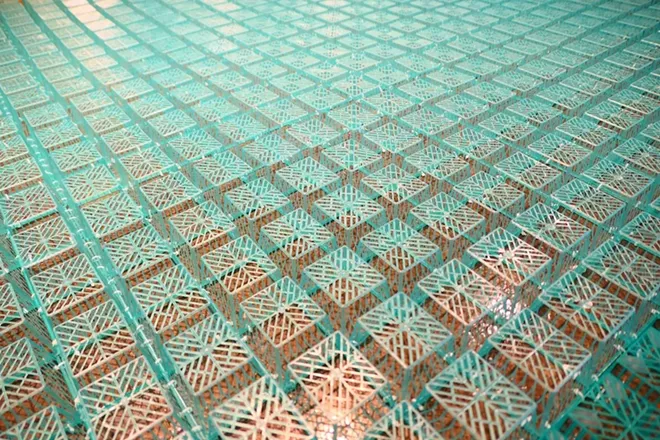

Drey took on the tedious task of stitching green plastic produce baskets into her Meadow — a 15-foot long grid she paired with pollinators and native plants. Curiously, she likened the piece to such contemplative landmarks as the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool.

“We have all these great memorials,” she mused. “So I thought, why don’t I take something like this and highlight the labor [involved] but also [celebrate] the life [it has]. So there is color in the work. And the idea [was] to lay out a field that has the potential to be what you want it to be as you sit in front of it and think about it. And that’s a meadow — where things grow wildly. And it gives you permission to do whatever it is that you need to move forward.”

Fields referenced her own identity as a citizen of the Osage Nation in The Memory of the Sun and The Earth Carries a Memory — mixed media-wall hangings that combine indigenous weaving techniques and verdant photographs of the Cahokia and Sugarloaf ceremonial mounds.

“This is our original homeland,” Fields said of Missouri’s Sugarloaf Mound. “And so I connect this to identity as who we are as people today, and use elements from our Osage clothing to pair that with that land.”

Additionally, Molina transformed her exhibition space into a conceptual greenhouse by presenting symbolic crops — including corn, bean, coffee and banana plants representative of her native El Salvador — as nourishing works of art.

“El Salvador fought for like 12 years in a civil war,” Molina explained. “And it lasted that long because the U.S. helped fund it. … I’m always thinking about the what if. What if the U.S. hadn’t intervened? What if we would have had a chance to stay? … We’re witnessing these violent mass deportations right now, [and] I’m constantly thinking about agency. What does it mean for us to have a say [about] where we stay and where we go? This garden has different things that are tied to ideas of return for me. A lot of [my] work is related to land and access to land — and who benefits from it.”

Molina added that she also loves growing food.

“It’s very much ingrained in me, [and] I think I’m pretty good at it,” she said with a laugh. “I think it’s a very ancestral desire.”

Bryan Rindfuss

Oklahoma-based Anita Fields referenced the Osage creation story in the sculptural installation When the Elk Created the Earth.

Fittingly, the artists became familiar with one another over a shared meal at a pizza joint near Artpace.

“When I met these beautiful ladies, we hit it off over pizza one night,” Fields recalled. “[It was] like two or three hours after we met and we just saw the threads kind of immediately.”

Upon hearing this factoid during the artists’ talk, one guest was determined to find out exactly which pizzeria they’d visited.

“Leo’s Hideout,” curator Jami Powell confirmed.

“I’ve been in restaurants my whole life, [and] I believe there’s something sacred about hospitality and good food,” the guest said. “And to hear y’all talk about how your relationship was sort of awakened and galvanized by pizza, it’s kind of inspiring to me.”

Shared meals continued throughout the residency, with the artists taking turns as providers.

“We were cooking for each other,” Drey said. “Lorena would bring things from her family’s garden to help feed us. And then one of us would rotate and cook something and share. We fed each other and cared for each other. And we kind of made our own Artpace garden where we tended to it with our love and our hard work.”

Family ties also emerged as a common theme. Drey’s piece Passerby: Americana entails a large-scale photograph of a familiar-looking field in the Rio Grande Valley that she snapped from a moving car during a road trip with her mother and her daughter.

Fields referenced the archival tags her grandmother made while working at the Osage Museum in her piece The Sun Leads You Home — a translucent house-like sculpture suspended from the ceiling and hovering above a pair of clay moccasins she modeled after traditional Osage footwear. She also collaborated with her son on a soundscape that adds depth to her exhibition.

“I know nothing about music,” Fields said. “I don’t know how [my son] became a fiddler … but I think it’s really beautiful. My whole family is involved in the arts, and so I bounced ideas with him. I don’t know quite how to explain it, but it’s very meaningful for me to be able to have his sound in there.”

Molina also collaborated with family members on a soundscape — one comprised of whistles and hums that bubble up from plastic water-collection barrels.

“I was thinking a lot about whistling and humming,” Molina said. “It’s something [we do] when we’re waiting. [And] this work is about waiting. This work is about wishing. But also, in the Civil War, [people] would use whistling as a secret language. So it’s almost like a call and response.”

Bryan Rindfuss

Houston-based Laura Veles Drey stitched together plastic produce bins to create her Artpace installation Meadow.

Furthering the familial involvement, Molina worked with her aunt, who lives in San Antonio, borrowing plants from her garden and using her kitchen to make jars of Salvadorian curtido (fermented vegetables) she presented like edible time capsules.

“I wanted to create an archive of the bacteria in her kitchen,” Molina said. “I think fermentation is pretty cool … and this is food that could potentially be used for the future.”

Touching on the growth, greenery and other common ground in all three exhibitions, Jami Powell recited Greek poet Dinos Christianopoulos’ oft-quoted couplet, “They tried to bury us, they didn’t know we were seeds.” Introduced in 1978, that refrain has evolved into a powerful message of resistance that’s very much in keeping with the collected works Powell helped bring to fruition.

But the curator’s key takeaway was the artists’ shared practice of “monumentalizing the mundane.” In addition to the unexpected applications of produce bins, plants and plastic barrels, those everyday elements of surprise included an American flag-inspired curtain Drey crafted from 8,000 twisty-ties, milk crates that Molina used as pedestals to uplift her work and a plastic elk that Fields spray-painted metallic gold.

“We all bounced ideas off of each other … [and] I was dreaming about this elk for two or three weeks … [and] it’s gotta be gold,” Fields said of her piece When the Elk Created the Earth, which references a legend about an elk that sacrificed itself to grant the Osage people fertile land. “[I decided] I’m going to do that — because the elk is really important in our Osage creation story. He created the earth.”

Reflecting on the Artpace residency, Fields summed it all up poetically, thanking Powell for “pulling the thread” that connected them all.

Subscribe to SA Current newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter| Or sign up for our RSS Feed

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content