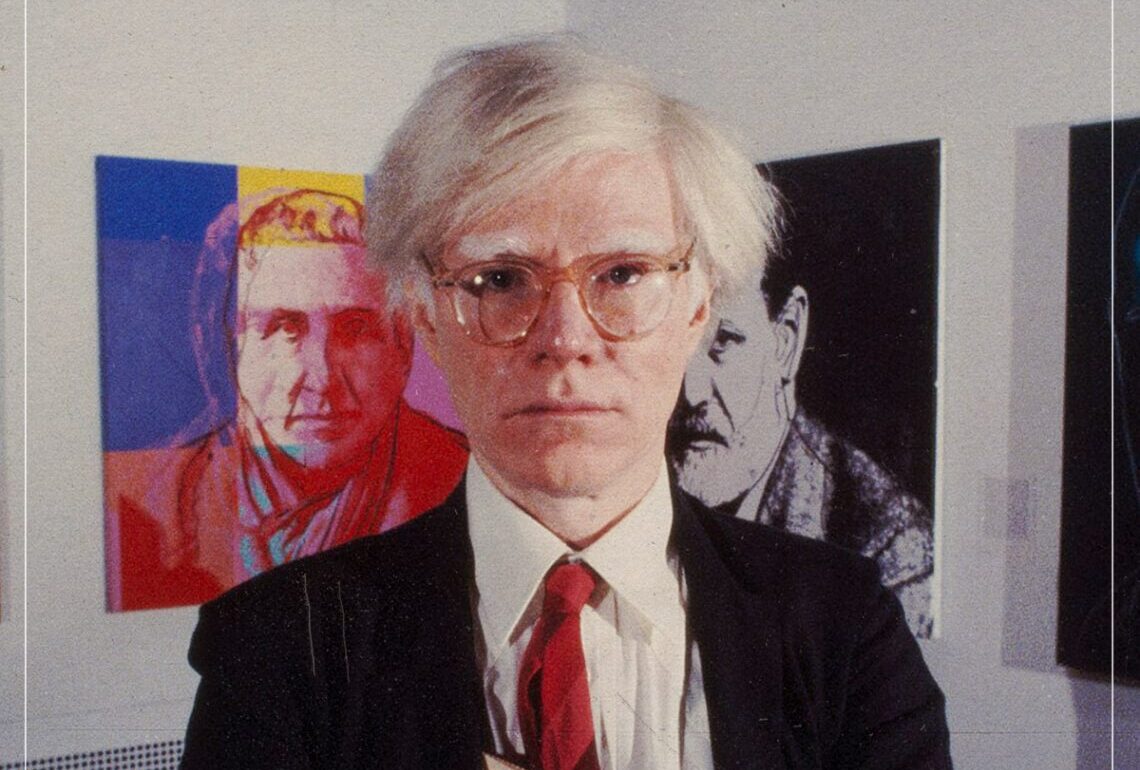

(Credits: Far Out / United States Library of Congress)

“I always thought I’d like my own tombstone to be blank. No epitaph, and no name. Well, actually, I’d like it to say ‘figment’.” That was Andy Warhol’s thought on death—at least what he made public. A myth of a man in every sense, art historians have wondered forever if anyone actually truly knew who Warhol was or whether any insight we could possibly get was merely another veiled layer or some persona. And after his brush with death in 1968, that veil became metal, it seemed. Andy Warhol wanted only to be a machine.

It could be argued that Warhol was a machine even before. There’s a reason why he called his office, The Factory. In that building, he was doing it all—painting, photography, and making movies. But it was a bustling room, packed with celebrities and superstars and mostly with other artists who made up his team. Warhol had always, to a degree, been a production line simply due to the nature of his medium. He made silkscreen prints, meaning that once he made his first, he could entrust the making of others to a team. That’s the reason why Warhols are visible around the world. He made a lot, and he had a lot of hands to help.

But there was heart, and the nature of pop art proves that. Warhol’s work was plugged into the world and the culture in which he existed. In short, the work felt alive. It felt reflective of being alive, young and fun. It also just happened to make him money and a star out of him.

Then, June 3rd, 1968, happened. Valerie Solanas, a radical feminist who felt scorned by Warhol, entered The Factory, had an argument with the artist, drew a gun and shot him. The bullet damaged his lungs, oesophagus, liver, spleen, and stomach. Warhol was briefly pronounced medically dead, but he survived.

There was “no new Warhol”, the artist said after the ordeal. “Don’t be silly”, he said dismissively before stating, “Before I thought it would be fun to be dead. Now I know it’s fun to be alive.” But as with everything Warhol said, it was veil after veil. Here we have a man who spent a whole life presenting himself as flippant about death when reality was the exact opposite following a traumatic childhood experience and now this. Warhol was terrified, and while he told the world he was fine, his true feelings always found a way to come out in his art.

In this case, they came out in his whole new ethos towards art. Warhol was now interested in ‘business art’. Pop art was dead. The man was now a machine, a money-maker, a cold, corporate, commercial figure.

“Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art”.

Andy Warhol

So what was Andy Warhol’s idea of business art?

“The new art is really a business,” Warhol said in 1969, “We want to sell shares of our company on the Wall Street stock market.” Later, he said, “I’m a commercial person”. He’d then bare it all, his new manifesto: “Business art is the step that comes after art. I started as a commercial artist, and I want to finish as a business artist. Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art.”

The figure was on a mission to be a businessman. Going completely against the typical attitude of an artist, Warhol was being upfront that his new and sole mission was to make money, be a brand, be a ‘figment’—perhaps all to avoid being a person.

He made more commissions for increasingly random people if they paid well. He upped the production of his prints, stopped making movies—they were a waste—and would put his name on anything, writing in an ad in The Village Voice, “I’ll endorse with my name any of the following; clothing AC-DC, cigarettes small tapes, sound equipment, ROCK ‘N’ ROLL RECORDS, anything, film, and film equipment, food, helium, whips, MONEY!! love and kisses ANDY WARHOL, EL 5-9941.” Hence, the huge number of Warhol collaborations that exist to this day with various brands. He got to work on a new series of prints, obsessively painting dollar signs. He closed the doors to The Factory, not because he was scared, no, he’d never admit that, but to focus—this was an office, a place of work.

“You’re a killer of art, you’re a killer of beauty, and you’re even a killer of laughter,” artist Willem de Kooning drunkenly yelled at Warhol at a party at the end of the 1960s. The artistic community was outraged, holding onto typical beliefs about an artist ‘selling out’, but Warhol’s move, as always, was more complex than that and more complex than he’d ever get into.

Maybe he’s right. Maybe business ar’ was the new frontier as Warhol truly broached new ground for what popularity, celebrity, and money-making mean to an artist. But there’s a humanness to Warhol’s desire to not be human. “I never understood why when you died, you didn’t just vanish; everything could just keep going on the way it was, only you just wouldn’t be there,” he once said, trying to deliver a signature Warholian quip but exposing a real anxiety there.

Warhol, in the wake of his assassination attempt, was reeling with what it would mean to die, what legacy would be left behind, how he wanted to be remembered and how he would ensure that happened, given the second chance at life he was thrown. But mostly, there was the question of how he would survive and process the trauma of it. Business art appears as a somewhat protective move. Warhol couldn’t be hurt again if he wasn’t a man, but just a name, a brand, a cold, untouchable thing, not the vulnerable human he was before.

Related Topics

Subscribe To The Far Out Newsletter

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content