When art preparator Rich Houck showed up to his part-time job on April 17 at the Freedman Gallery at Albright College, in Reading, Pennsylvania, he found the storage space mostly emptied out, racks vacant, the room left in disarray. He knew that the college was planning to sell the collection to raise funds, but no one had notified him that the works would actually be moved. Which works had been taken? Where? By whom?

In the absence of any other staffers—the two full-time employees were no longer with the college—he felt it was down to him to file a report with security. Not to worry, he was told. Vice president of administration James Gaddy had ordered the move and said no one should file a report.

Houck wasn’t satisfied with that. But the problem would soon be out of his hands. Despite eight years of employment, with what he said were good performance reviews, he was fired on April 29, he said, supposedly for not upholding professional standards.

Indeed, the college was doing its best to keep quiet the fact that it is selling off the Freedman Gallery collection, which includes works by artists such as Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Salvador Dalí, Jasper Johns, Jacob Lawrence, and Robert Rauschenberg, to help meet a budget shortfall that was recently as high as $23 million. Many in the community are unhappy. Major donors were not informed.

Empty storage racks at the Freedman Gallery at Albright College. Photo: Rich Houck.

The sale is part of a much larger campaign to cut expenses and generate revenue. Over the course of 2024, the school cut 53 positions, canceled some academic majors, and considered selling some real estate in addition to the art holdings, reported WFMZ in January; insiders said dozens more have since been let go. The school also petitioned Orphans’ Court in December to approve an emergency appeal to borrow up to $25 million against the school’s endowment.

Former Freedman Gallery staffers—acting director/curator David Tanner, also dean of arts and cultural resources; and Kate Mishriki, registrar and collections manager—are no longer in their positions. College president Jacquelyn Fetrow resigned in May 2024 after campus protests over the school’s financial woes; she had been in the position since 2017.

From Alechinsky to Wilke, a Collection Rich in Distinguished Names

An Artstor directory of the Freedman Gallery collection lists 1,053 items. One source with direct knowledge of the collection said that number accounts for less than half the collection. The Artstor listing includes works by artists, in addition to those named above, such as Pierre Alechinsky, Eleanor Antin, Karel Appel, March Avery, Hans Bellmer, Chryssa, Chris Burden, Robert Colescott, Dalí (represented by some 65 works), Jim Dine, Rosalyn Drexler, Audrey Flack, Buckminster Fuller, Francoise Gilot, Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Red Grooms, Komar and Melamid, Roberto Matta, Henry Moore, Claes Oldenberg, Gordon Parks, Larry Rivers, James Rosenquist, Leonid Sokov (represented by some 112 works), Rafael Soto, Rufino Tamayo, Mark Tobey, Victor Vasarely, Esteban Vicente, Tom Wesselmann, Brett Weston (137 works), and Hannah Wilke.

The gallery was named for Doris C. Freedman, the first director of New York’s Public Art Fund (PAF), for whom the plaza at Central Park’s southeast corner, where PAF regularly displays artworks, is named. She also was president of the Municipal Art Society, served as New York’s first director of cultural affairs, and was instrumental in developing New York’s Percent for Art program. She graduated from Albright in 1950 and helped fund the creation of the gallery, whose mission is to focus on postwar American art, with a major gift in 1975.

Freedman’s three daughters were unaware of the pending sale.

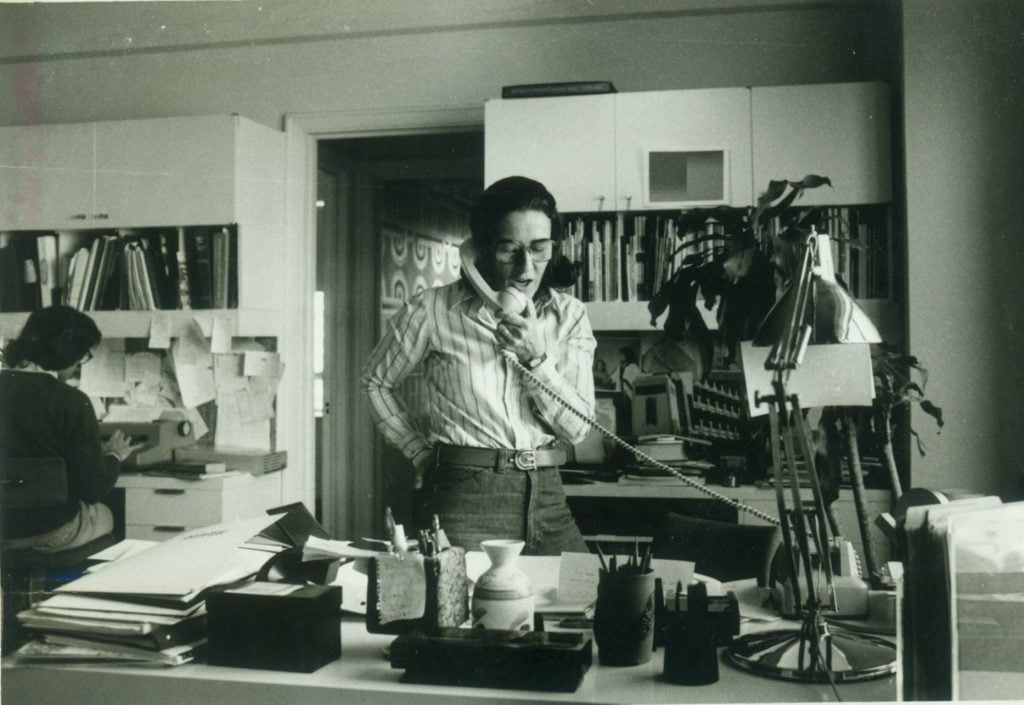

Doris Chanin Freedman on the phone at the Public Art Fund office. Courtesy Public Art Fund.

“We believe that Albright College’s decision to monetize the art collection of the Freedman Gallery is both shortsighted and counterproductive,” said Karen J. Freedman, Nina P. Freedman, and Susan K. Freedman in a statement to Artnet News. “When our parents donated funds to Albright to create the Doris C. Freedman Gallery, the donation had two purposes. The first was to honor our mother, the first Director of Cultural Affairs for New York City, the founder of the Public Art Fund in NYC, and an Albright alumna. The second was to create a space where the arts would flourish—a space for students and the Reading, Pennsylvania community to engage with the arts.

“Our family was never notified of the plan to sell key elements of the Freedman Gallery’s art collection to repay outstanding debt, and we are shocked that, absent notice provided by Artnet, we would not have any knowledge of the intention to gut the art collection, essentially alter the intent of the donation to Albright, and transform the Freedman Gallery from a thriving draw to the school into what will now become little more than a hallway,” they said.

“Based on legal precedent set by other educational institutions that have attempted to raise revenue by selling their art collections, we have serious doubts as to the legality of this decision,” the sisters added. “We look forward to the possibility of a dialogue with Albright to resolve this issue.”

Susan K. Freedman is president of the board for the Public Art Fund. Attorney Karen J. Freedman heads up New York’s Silverweed Foundation, which has been a major supporter of the gallery. Nina P. Freedman worked in the administration of mayor Michael Bloomberg before joining Bloomberg LP as a member of its global philanthropy and engagement team.

Much of the collection—one insider said perhaps as much as half—was donated by Alex Rosenberg, a New York art dealer and alumnus. His daughter, Carole Rosenberg, was taken by surprise by news of the sale, conveyed in a phone conversation.

Informing the Freedman and Rosenberg families of the pending sales, said college president Debra Townsley in a phone interview, “is something we probably should have done up front.”

Do Professional Standards Apply to Unaccredited Institutions?

A representative of the school brushed off any concerns in a May 19 email.

“Albright College is no longer a collecting institution and is not, nor has it ever been, accredited by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM),” said press officer William E. Martinko, adding that for that reason, “there are no restrictions or accreditation-related issues with dispersing the current collection. We’re incredibly excited to be working with local partners to allow these works to find new homes where they can continue to inspire and be appreciated.”

Artworks on display at the Freedman Gallery at Albright College. Photo: Rich Houck.

The college had developed a collections management policy in 2013 governing the sale of artworks (known as deaccessioning in museum lingo), reviewed by Artnet News. It stated: “De-accessioning will be conducted according to the rules and regulations of the American Alliance of Museums’ standards. The Gallery may, as a courtesy, but is not required to (unless as a condition of the gift), notify donors, descendants, relatives, etc. of the College’s intent to de-accession the object.” The document outlines several conditions that must be met to sell artworks.

But, in an October 18, 2024 email, Gaddy informed Gallery staff: “The board has made the difficult decision to rescind Albright College’s collection policy and dissolve the Visual Arts Committee. Additionally, we will be moving forward with the sale of the Albright Art Collection.”

Townsley pointed out in our interview that Albright is one of many colleges facing a financial crunch, especially after enrollment numbers dropped during the pandemic. Having led five struggling colleges, she said, she specializes in “turnarounds.” She’s confident she can right the ship, and speaks proudly about Albright’s record in helping students climb the socioeconomic ladder. Whereas the school had been facing a $23 million deficit, she said, this year the school should run a $2 or $3 million profit.

Albright College president Debra Townsley. Courtesy Albright College.

“When it came to the artwork, we are not a museum, that is not our business, and we don’t have the talent or the controlled environment for artwork,” she said in an interview. “It’s outside of our mission. So my feeling is, look, we should sell the artwork to people where it is their mission. They can take care of the artworks and do it right.” The college is working with area institutions that can preserve regionally significant artworks, she said, so she’s unable to say how much of the collection will be offered for sale.

But she guesses that the sale will likely only net a few hundred thousand dollars. This sale, she acknowledged, “isn’t going to save the school.”

Pennsylvania auctioneer Pook and Pook is handling the auction over two days in July; the contents of the sale will be published in early July, said the house in an email, adding that the auction will include “hundreds of lots of modern art, prints, and posters.”

Courtesy Albright College.

Asked about whether Pook and Pook is the house that can deliver the best value, Townsley said, “We did go to several auction houses and had them look over [the collection], and Pook and Pook seemed to be the best for what we had.”

Professional guidelines set by organizations such as AAM, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), and the Association of Academic Museums and Galleries prohibit member museums from selling artworks to raise funds for purposes other than purchasing more artworks; museums cannot sell artworks to raise general operating funds without being subjected to official sanctions. Those associations, along with the Association of Art Museum Curators, condemned, for example, the recent sale by Indiana’s Valparaiso University of works by Frederic Church, Childe Hassam, and Georgia O’Keeffe to raise funds to renovate freshman dormitories.

The Freedman Gallery was not accredited by the AAM, as AAM confirmed in an email, but, according to two insiders, former staffers had worked for years toward meeting the organization’s requirements for accreditation.

A larger problem is that, according to two people with knowledge of the situation, substantial parts of the collection may not have clear title, since record-keeping was not consistent over much of the gallery’s lifetime. Townsley said records for each piece will be reviewed to ensure the donor’s wishes are honored.

Artwork on view in an office at Albright College. Photo: Rich Houck.

WFMZ reported that the school was in contact with the Reading Public Museum about the possibility of displaying or purchasing some works from the collection; according to a statement from Reading, nothing has been decided on that front.

“For some time, the Reading Public Museum has been engaging with our counterparts at Albright concerning the future of their institutional collection and the possibility of acquiring a portion of their holdings,” said director and CEO Geoffrey K. Fleming in an email. “While we have not yet made any formal decisions, those discussions are ongoing and we hope they may lead to a positive outcome for Albright and the greater Reading community.”

An Administrator with a Cloudy Past Spearheads a Sale

Executing the plan to sell the collection on orders of president Townsley is vice president Gaddy, who has something of a checkered history in higher education. He resigned in 2020 as deputy director at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University after a months-long investigation into a toxic work culture. Previous to that, he was vice president of human resources and Title IX coordinator at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia when two students said they were raped by a fellow student and got little satisfaction after filing complaints.

Albright apparently tested the waters by selling Alice Baber’s painting The Light of the River (1979), which it offered in November at Freeman’s | Hindman as lot 1 in a postwar and contemporary art sale; it fell short of its $30,000 low estimate, fetching $25,400.

One insider estimated that under the best circumstances, selling the collection will net the college less than $1 million. But, ethical concerns aside, it is not the most auspicious moment for an art collection to come to the block. The auction market has contracted strongly in each of the past two years. In 2024, sales dropped 27.3 percent, to $10.2 billion, continuing a downward trend that started in 2023, per Artnet’s Intelligence Report: The Year Ahead 2025.

“There are members of the community who are very, very opposed to this,” said Jaap van Liere, a graduate who headed the Visual Arts Committee that was dissolved in 2024, in a phone interview. “There are others who understand the school is in dire financial straits, and an asset is an asset.

“But they’re not going to get a lot of money for it,” he said, “and so why take the grief?”

Townsley, in the end, stands by the school’s decision.

“We’re not just putting it out at a flea market,” she said.” It’s important to treat it with the respect it deserves and we’re trying to do that to the best of our ability. Those are the kind of tough decisions you make in a turnaround.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content