Abstract

The relationship between historical culture and tourists’ perceptions is key to sustainable heritage tourism. Wulin Village, blending Chinese, Nanyang, and Western cultures, offers a unique case. This study employs social network analysis (SNA) to develop a three-dimensional “architecture space—auspicious culture—perceived image” network model, exploring their interconnections and impact on heritage conservation and tourism. Findings show tourists value architectural style and history but are aware auspicious cultural patterns, especially online. Offline tourists link Minnan culture with emotions; online tourists perceive it through architecture. The fusion of auspicious patterns with Western architectural elements reflects cultural diversity, boosting tourists’ cultural identity and emotional ties. The model identifies key heritage areas, guiding targeted protection and planning. As a novel quantitative framework, it offers broad international applicability for studying cultural heritage and tourism, providing new insights and promoting sustainable global heritage conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, the preservation and transmission of cultural heritage is receiving increasing attention1. Through initiatives like the World Heritage List, UNESCO is dedicated to safeguarding each country’s unique cultural and natural heritage, emphasizing the importance of cultural diversity to the global community2. Cultural heritage not only serves as a testament to history but also plays a crucial role in cultural identity and contemporary societal development. In this context, traditional villages, which embody unique social histories, ecological values, cultural landscapes, and architectural esthetics, have become a key focus of cultural heritage research. Minnan represents the southeastern region of China’s Fujian Province, which has a unique geographic and historical culture that blends the cultures of Southeast Asia, Taiwan, and northern China3. In China, the villages of Minnan represent a historical legacy shaped by a distinctly multicultural context. Since the Ming Dynasty, many people from Minnan migrated to Southeast Asia for economic reasons, bringing back diverse cultures, customs, and beliefs, a phenomenon known as “Going to the Nanyang”. This cultural exchange allowed Minnan to absorb Southeast Asian and Western influences, enriching its local traditions. In Minnan villages, traditional earthen buildings coexist with architectural styles influenced by Southeast Asian and Western designs. This blending of cultural elements creates a distinctive architectural diversity, particularly evident in the auspicious decorations on buildings. These structures feature carvings and patterns that integrate floral and animal patterns from Southeast Asia with traditional Chinese auspicious symbols. These decorations not only have esthetic value but also convey symbolic meanings from multiple cultures.

The rapid pace of globalization, combined with China’s swift urban and rural development, has posed significant challenges to the spatial structure and preservation of auspicious culture in Minnan villages. Rural tourism development, while driving economic growth, often disrupts traditional spatial layouts, architectural styles, and decorative elements due to industrialization and homogenization. Conflicts between tourism development and cultural heritage preservation have also emerged. Developers tend to prioritize the renovation and commercialization of cultural spaces, overlooking their role in transmitting intangible cultural heritage. This neglect weakens tourists’ cultural identity, making it harder for them to perceive the distinctiveness of local culture. Furthermore, cultural spaces tied to intangible heritage, such as ceremonial sites for traditional festivals, are disappearing, threatening the continuity of intangible heritage and creating a disconnect between the material and intangible aspects of these landscapes. In response, scholars are increasingly focused on revitalizing traditional village heritage through tourism development4. Research now addresses the maintenance and restoration of village spatial forms5, historic buildings6, and ecological landscapes7. Some scholars have also explored the relationship between village spatial development and socio-cultural factors, including indigenous social networks8, community participation9, and cultural beliefs10. However, most research on village culture still centers on cultural identification and assessment11, with limited quantitative studies examining the relationship between village architecture and cultural perception. This study, therefore, aims to explore whether a correlation exists between spatial structure, auspicious patterns, and tourists’ cultural perceptions and whether tourists can still discern distinctive cultural characteristics in the context of village development.

This study, combining social network analysis, innovatively constructs a three-dimensional network model of “architecture space—auspicious culture—perceived image” and explores the perceived characteristics of auspicious cultural elements and their interrelationships in the traditional architecture of Minnan. The study is organized into three main sections: First, it provides a comprehensive overview of the architectural styles, multicultural influences, and tourism development in traditional Minnan villages, highlighting the region’s unique cultural background and rich heritage resources. Second, it analyzes the structure of the three-dimensional network model of “architecture space–auspicious culture–perceived image”, exploring the interactions between the auspicious culture network, the architecture space network, and the perceived image network. This section reveals how these interconnections collectively shape tourists’ cultural cognition and emotional attachment to the villages. Lastly, from the perspective of tourists’ perceptions, it emphasizes the importance of preserving and inheriting the architectural spatial structure and auspicious patterns for heritage conservation and sustainable tourism development and proposes corresponding strategies and methods. This study aims to quantitatively assess the impact of factors such as architectural style and auspicious cultural patterns on tourists’ perceptions by constructing a three-dimensional network model, and to explore how these elements work together to shape tourists’ cultural perceptions and emotional connections to heritage villages, which provides new strategies and suggestions for heritage conservation and tourism development. In addition, the innovative model proposed by the study not only provides effective support for the quantitative assessment and planning of heritage tourism villages, but also provides a new methodology for cultural heritage conservation and tourism development around the world. Meanwhile, this model can help researchers and policymakers to be able to assess the heritage and development potential of cultural heritage more scientifically, promote the sustainable conservation and development of cultural heritage around the world, and provide a solid theoretical foundation and practical guidance for the construction of heritage tourism and cultural ecosystems in the future.

The concept of social networks originated from Radcliffe–Brown’s structural research, which focused on studying the interrelationships among actors in social activities, such as kinship, neighborhood, and tenancy, and uncovering underlying structures through relational data, images, and models12,13. Social network analysis has since expanded beyond human relations and is now widely applied in fields like human geography, tourism management14, and history. In recent years, social network research has expanded into fields like cultural tourism, urban planning15, and architecture, addressing both material and spiritual culture networks16,17. The study of physical space networks occurs at two levels: macro and micro. Macro-level research focuses on the spatial structure and organization of urban agglomerations, examining spatial interactions18, transportation systems19, and spatial effects20. For example, Zeng et al. applied social network analysis with remote sensing data to reveal the spatial network characteristics of eco-efficiency in urban agglomerations along the Yangtze River, highlighting the influence of node space on eco-efficiency21. Similarly, Hui et al. explored the relationship between economic growth and spatial structure in mega-city regions, emphasizing the role of transport infrastructure22. At the micro level, the research examines the street structure and morphology23, historic neighborhood preservation and renewal24, and the structural organization of villages and communities25. Porta et al. developed a network model of six urban streets, showing that higher-ranking roads typically connect to lower-ranking ones and that most street networks exhibit small-world characteristics26. Liu et al. in a study of eight urbanized villages, found that new-generation immigrants are less likely to engage with spatial boundary networks, increasing social distance27. Recent research increasingly focuses on the intersection of material networks and spiritual-cultural dynamics. Studies on spiritual–cultural networks examine kinship and neighborhood28, religious belief29, and cultural networks. Tian et al. demonstrated that village acquaintanceship, measured by node degree and node symmetry index (NSI), plays a key role in village reconstruction30. Qi et al. used the TF-IDF algorithm to classify traditional cultural elements, revealing a ring-shaped distribution of traditional Chinese culture31. In summary, social network studies have shifted from focusing solely on material spatial networks in cities, communities, and villages to incorporating spiritual-cultural networks, reflecting the growing integration of cultural elements into network analysis.

The concept of the tourist destination image originated from John Hunt’s research in the 1970s32. It refers to tourists’ comprehensive perceptions of a destination, including spatial environment, cultural background, and emotional evaluation33. This concept draws from fields such as social psychology, communication, and geography. Current research on tourist destination image focuses on three main aspects: perceived image, emotional image, and media-communicated image34,35. Research on perceived image emphasizes the objective existence of tourism resources and historical contexts36. For instance, Xiao et al. used a convolutional neural network (CNN) to analyze tourist photos, revealing spatial and temporal heterogeneity in tourist images37. McCartney’s study of airports in four cities found that tourists from different cultural backgrounds perceive destinations differently, which extends to social activities in these places38. Research on affective images examines emotional expectations and how emotional variability influences destination images39. Basaran et al., using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), showed that tourists’ emotions toward destinations are linked to their perceptions, allowing predictions of their likelihood to revisit40. Similarly, Kim et al. found a positive correlation between media webpage design and tourists’ emotional perceptions41. Research on media-communicated images focuses on how these images are conveyed through newspapers, magazines, online media, and personal sources. Pan et al. used a discrete model to show that the tourist destination image communicated through social networks significantly influences tourists’ behavior and intentions42. Choi et al., through content analysis, revealed discrepancies between the expected and perceived online image of Macau35.

In summary, research on tourist destination images has shifted from analyzing objective resources to exploring tourists’ perceptions, with increasing attention to cultural factors. Interest is also growing in the relationship between spatial information and culturally perceived destination images. While some studies have examined cultural elements in social networks and destination images, the mechanisms through which cultural factors influence these areas remain underexplored. In particular, the impact of cultural differences on network structures and image perception in multicultural contexts requires further investigation. Moreover, there is a lack of research in rural heritage studies examining the relationship between village spatial structure and auspicious culture from a cultural perception perspective. This study aims to explore the relationships between the auspicious cultural network, architecture space network, and perceived image network in Minnan village, revealing interactions between spatial structure, decorative patterns, and tourist perceptions, and identifying key influencing factors. The findings will offer new insights and provide theoretical support for future research.

Methods

Research area and sample selection

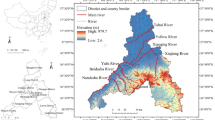

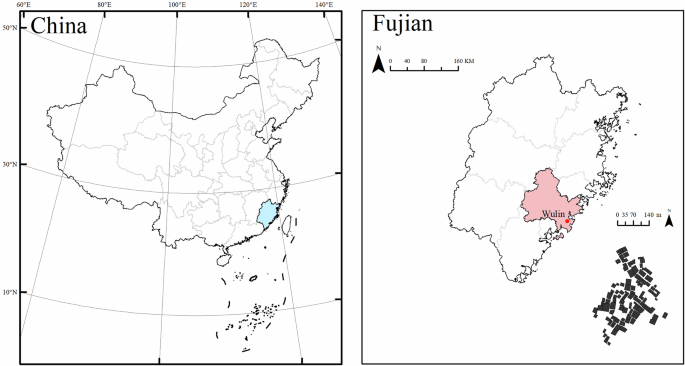

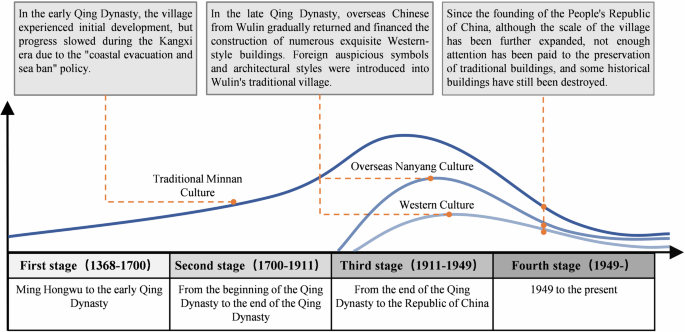

The study area is located in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, Southeast China (N 24°30′44”–24°54′21”, E 118°24′56”~118° 41′10”). With its unique geography and rich history, Quanzhou has become a significant center for cultural exchange, particularly along the Maritime Silk Road. Historically, Quanzhou served as a cultural hub and was designated a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site in 2012 under the title “Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China”. Wulin Village, in southern Quanzhou, is the focus of this study. Historically known as the “Three-Legged Basket”, Wulin Village is a typical Minnan village (see Fig. 1). Established during the Hongwu period of the Ming Dynasty, the village developed through the Qing Dynasty, flourished in the late Qing and early Republic of China periods, and stabilized after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Its history spans over 600 years (see Fig. 2). Wulin Village’s architectural heritage is well-preserved, diverse, and concentrated, featuring Minnan traditional houses, Fanzai buildings, and Western-style houses, including Romanesque, Gothic, and Spanish designs. The village also has a rich array of architectural decorations, such as gray sculptures, wood and brick carvings, and colorful paintings. These decorations incorporate themes of flora, birds, auspicious symbols, and human figures, often reflecting foreign influences from Nanyang. Wulin Village exemplifies the distinctiveness, cultural significance, and diversity of heritage in its geography, cultural lineage, architecture, and decorative traditions. This multicultural blend provides valuable insights into tourists’ perceptions of destination image, highlighting their experiences and emotional responses in diverse cultural settings.

Location of Wulin Village in China and Fujian Province. The legend for the map on the left provides the following information: The “International boundary” is represented by a solid line. The “Boundary of province” is depicted using a gray line. Fujian province is highlighted in light blue on the map. The legend for the map on the right provides the following information: The “Municipal boundary” is represented by a gray line. The “Study area” is indicated by a red dot. Quanzhou is highlighted in light pink on the map. The “Boundary of province” is depicted using a solid line.

Since Wulin Village was designated as a Chinese traditional village in 2016 and the Quanzhou government launched the “Minnan Overseas Chinese Cultural Resort Project”, its tourism development has grown significantly. By 2021, it was upgraded to a national 4A-level tourist attraction and has become increasingly popular. Wulin Village has effectively used marketing channels, including social media and tourism websites, to promote its unique features. Tourists are especially attracted to its “unique Overseas Chinese architecture”, a key highlight. However, several issues need attention. First, tourists have a limited understanding of the village’s architectural style and multicultural heritage. While the architecture is distinctive, many tourists are unaware of its historical and cultural significance, hindering their full appreciation of its diverse cultural elements. Second, the homogenization of tourism products is a growing concern. As idle land around the village is developed for homestay tourism, many newly constructed imitation buildings lack originality and distinctiveness. This proliferation of mass-produced buildings and tourism products diminishes tourists’ satisfaction and cultural engagement. Additionally, these trends constrain the creative development and dissemination of rural heritage, limiting its potential in cultural tourism. This study focuses on Wulin Village to explore the integration of auspicious architectural culture with tourists’ perceptions. It aims to enhance understanding of the village’s unique multicultural charm while identifying the challenges facing rural heritage. The findings will support the sustainable development of rural heritage tourism.

According to the Wulin Village Protection and Development Plan of Xintang Street, Jinjiang City (2017), Wulin Village is divided into three areas: the core conservation area, the construction control area, and the environmental coordination area. The core conservation area contains the best-preserved and most historically significant parts of the village. The construction control area strictly regulates new buildings and alterations, while the environmental coordination area ensures harmony between the village and its surroundings. In the core conservation area, street patterns and spatial textures are well-preserved. This area also features traditional buildings, landscape systems, and fortifications, exemplifying the originality of Minnan Village style and preserving the historical atmosphere of Wulin Village. The core conservation area receives the highest number of tourists, who are drawn to its strong representation of Minnan and overseas Chinese culture. Due to its rich historical and cultural heritage, the core conservation area was selected as the research sample for the study of Wulin Village. Table 1 lists the types of cultural heritage found in the village.

Data sources and processing

The village base data includes the history of the village of Wulin Village and the base information from the Chinese Traditional Villages Archives (Wulin Community), Detailed Construction Planning Design of Wulin Community in Jinjiang (2017), and the Wulin Village Conservation and Development Planning Instruction of Xintang Street in Jinjiang City. These records provide comprehensive information on the village’s environment, cultural significance, architectural layout, styles, and construction craftsmanship.

Data sources and processing of auspicious cultural, in January 2024, a site visit to Wulin Village was conducted to document and photograph the auspicious cultural elements of traditional buildings in the Core Reserve. These elements were categorized into three groups: traditional Minnan culture, overseas Nanyang culture, and Western culture. Ucinet 6.0 software was used to construct a network model of these auspicious cultural elements.

Architecture space and Node Data: Fieldwork in January 2024 documented Wulin Village’s current conditions, including the street structure, architectural styles, and natural landscape. Each building was treated as a “node” and roads as “lines” connecting them. AutoCAD was used to create floor plans based on aerial satellite maps, which were then imported into ArcGIS to process connection relationships. Ucinet 6.0 software was used to build the architecture space network model.

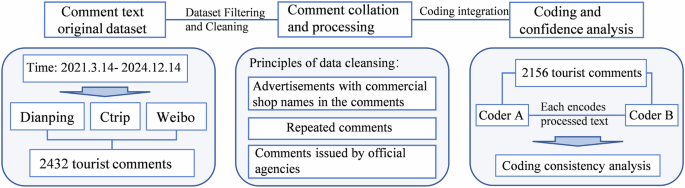

Data sources and processing of the perceived image, in this study, perceived image data are mainly derived from tourists’ comments posted on three open platforms, namely, Dianping.com (http://www.dianping.com), Weibo.com (https://weibo.com), and Ctrip.com (http://www.ctrip.com). These platforms are independent third-party consumer comment sites in China, similar to Yelp, that provide users with various services including travel business information, consumer comments, and promotional content43. As an open platform, consumers can share real-time comments and reflections on various aspects of the destination such as environment, dining, architecture, and culture. For in-depth analysis, we used Python 3.12.3 to collect 2432 publicly posted comment texts and their corresponding posting times between 14 March 2021 and 14 December 2024 on Dianping.com, Weibo.com, and Ctrip.com. To ensure the accuracy of the research data and the scientific validity of the research results, we cleaned the raw data appropriately44, with the following procedures: Firstly, exclusion of promotional content. We removed comments that appeared to be promotional or advertisements. This included comments with excessive references to shop names or posts that seemed to solicit tourists, as these could skew the authenticity of the perceptions shared by general tourists. Secondly, the removal of duplicates. Given the influence of online communication mechanisms, individual tourists sometimes post highly overlapping comments. To avoid redundancy and overrepresentation, we removed duplicate comments to ensure the dataset reflected unique user experiences. Thirdly, the exclusion of official or promotional posts. Comments posted by official organizations or media outlets, often featuring promotional content or marketing material, were excluded from the dataset. These comments were not reflective of general tourist perceptions and could distort the analysis of genuine tourist experiences. Finally, after applying these principles, we retained 2156 valid tourist comments for analysis. We then used Nvivo 11 and ROST CM 6.0 software to process the data, focusing on lexicon analysis and high-frequency words. Finally, we constructed a social network model using Ucinet 6.0 software to study tourist-perceived images. This process not only deepened our understanding of tourists’ perceptions of specific attractions but also laid the groundwork for further exploration of the factors influencing tourists’ experiences (see Fig. 3).

Model construction

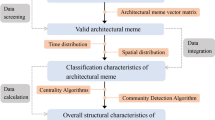

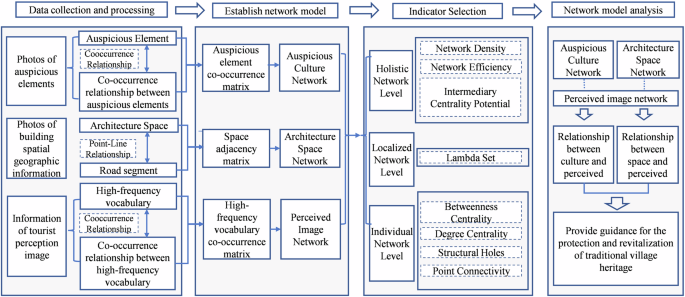

This study employs the questionnaire survey method and social network analysis. The research framework of the social network analysis method is divided into several key steps, including data collection and processing, network model construction, model index selection, and network model analysis (see Fig. 4).

Stept1 was a questionnaire survey method and data collection. A questionnaire was used to increase the diversity and accuracy of the data. We went to Wulin Village from 15 January 2025 to 20 January 2025 to conduct a questionnaire survey. During the study, 79 questionnaires were distributed, with 69 valid responses collected from tourists in Wulin Village. Participants’ personal information was kept confidential, and informed consent was obtained by ethical guidelines for human subjects. To assess tourists’ perception and experience of auspicious cultural elements, we used an evaluation scale of 0–5, with 0 indicating no perception and 5 indicating very much perception, to analyze the three dimensions of auspicious cultural perception, visual perception, and cultural experience (please see Supplementary Data A).

Stept2 was establishing a network of auspicious culture. The architectural decorative patterns in Wulin Village are rooted in traditional culture, and the various auspicious cultural elements collectively form the village’s auspicious cultural network. These patterns not only serve as physical representations of auspicious culture but also act as material carriers of traditional culture. The construction of the auspicious cultural network follows three steps. First, the architectural auspicious patterns are treated as nodes, and their co-occurrence indicates a direct link between these nodes. Second, if two nodes appear simultaneously, the co-occurrence is recorded as 1; if not, it is recorded as 045. Finally, a co-occurrence matrix of the auspicious cultural elements is established, and Ucinet 6.0 software is used to construct the auspicious cultural network model.

Stept3 was establishing a network of architecture space. Broadly, architecture defines spatial structure as the functional attributes, organization, and interrelationships of buildings, while spatial form represents the physical manifestation of this structure. In traditional villages, architectural spatial structure refers to the layout and intricate organization of building clusters, which are shaped by unique regional cultures, historical periods, and natural environments. From a network perspective, the architecture space of traditional villages can be viewed as nodes, with the network model reflecting the spatial organization46. The construction of the architecture space network model involves three steps. First, each architecture space is treated as a node (J), and roads connecting these spaces are considered edges. Second, if a node is directly connected to another or via an adjacent road, the connection is recorded as 1; if no direct road connection exists, it is recorded as 0, establishing the relationship matrix. Given the complexity of the village’s spaces and roads, architectural spaces are defined as enclosed areas, such as courtyards in front of and behind buildings, while roads are defined as segments uninterrupted by intersections. Finally, Ucinet 6.0 software was used to construct the architecture space topology model.

Stept4 was establishing a network of perceived images. In the perceived image network, high-frequency words related to tourists’ perceptions are processed using Nvivo11 and ROST CM 6.0 software. These high-frequency words serve as nodes, and their co-occurrence represents a relationship between them. By analyzing the frequency of co-occurring words, changes in popular topics can be identified. If two nodes co-occur, it is recorded as 1; otherwise, it is recorded as 047. Synonymous keywords are merged to account for variations in tourists’ descriptions. Finally, a co-occurrence matrix of high-frequency words was created, and the perceived image network model was built using Ucinet 6.0 software.

Stept5 was the network model index selection. The analysis of the auspicious culture network, architecture space network, and perceived image network is conducted at three levels: holistic network, localized network, and individual network. At the holistic network level, metrics include network density, network efficiency, and intermediate centrality. At the localized network level, lambda sets are used. At the individual network level, metrics such as betweenness centrality, degree centrality, structural holes, and connectivity are selected, as shown in Table 2.

Results

Connotation of auspicious cultural elements in Wulin Village

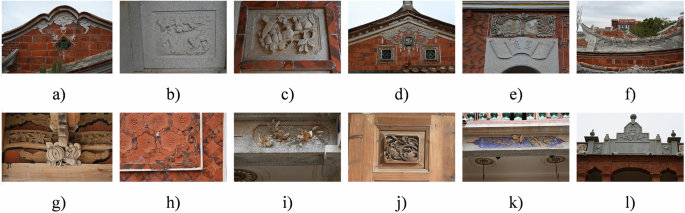

Wulin Village has seamlessly integrated traditional Minnan culture with foreign influences, forming a distinctive Minnan Overseas Chinese culture. The architectural decorations of Wulin Village’s traditional residences incorporate a variety of harmonious themes, fables, and symbols, enriching the auspicious cultural elements with deep cultural significance. For example, the pairing of the magpie and plum blossom symbolizes “joyfulness”, the combination of the dragon and phoenix represents “good fortune”, and the octopus signifies “returning home with abundance”. These auspicious cultural elements not only reflect the aspirations of the Minnan people for a better life but also serve as key carriers for the development and dissemination of Minnan culture. Through these symbolic decorations, the buildings possess not only esthetic value but also embody rich cultural traditions, highlighting the uniqueness and continuity of Minnan culture (see Table 3 and Fig. 5).

Online comments text content analysis

In tourists’ online evaluations of Wulin Village, frequently mentioned words highlight the most perceived aspects. Analyzing these high-frequency words identifies key topics. Using Nvivo11 and ROST CM 6.0 software, we conducted a word frequency analysis of 2156 text entries, identifying 40 high-frequency words related to Wulin Village’s perceived image (see Table 4). From this, 12 sub-themes emerged: “architectural style”, “architectural decoration”, “historical buildings”, “cleanliness”, “spatial openness”, “spatial accessibility”, “traditional Minnan culture”, “overseas Nanyang culture”, “western culture”, “natural resources”, “social resources”, and “tourism services”. These were grouped into four core themes: “esthetic characteristics”, “spatial vitality”, “history and culture”, and “tourism resources”.

Given the large number of online comment texts and the subjective differences in lexical thematic categorization between researchers, the identified analytical categories were analyzed inductively qualitatively and tested for reliability. The analysis consisted of two steps; firstly, the online comment texts were independently coded by two coders based on the analyzed categories identified for high-frequency words. Secondly, the consistency between the codes of the two coders was tested using the Kappa coefficient, a statistical method for assessing inter-observer agreement, which is widely used in content analysis48,49. Kappa values between 0.6 and 0.8 indicate good categorical consistency, and kappa values greater than 0.8 indicate excellent categorical consistency50. The Cohen’s Kappa (K = 0.726) obtained in this study indicates that there is sufficient reliability among the different coders that the variability of the coding results under the established analyzed categories is small and the reliability is within a manageable range. This indicates a consensus among coders, validating the use of the established analytical categories.

Online high-frequency words were classified according to the analyzed categories above. The analysis shows that tourists’ perception of Wulin Village’s history and culture is stronger than other themes. This reflects the village’s rich cultural elements, including historical buildings, folk festivals, and traditional crafts, offering tourists insight into its historical development. Tourists also highly regard the village’s architectural esthetics, particularly its preserved Minnan styles, such as red brick walls, swallow-tail ridges, and carved windows, which add visual appeal. The preservation of historical buildings enhances tourists’ appreciation of the village’s architectural heritage, with its blend of historical and cultural values leaving a lasting impression, especially in terms of esthetics (see Table 5).

Comparison analysis of online comment photos and offline comment photos

According to the statistical results of the questionnaire survey. The results showed mean scores of 3.79 for cultural cognition, 3.57 for visual perception, and 3.67 for cultural experience, indicating a medium-high level of recognition and engagement with auspicious culture. Notably, the mean score for tourists’ attention to and identification of traditional Minnan auspicious cultural elements was 4.0, demonstrating strong recognition of these elements, which stood out due to their quantity and diversity. The preservation of architectural heritage in Wulin Village further enhances tourists’ positive perceptions of these cultural elements.

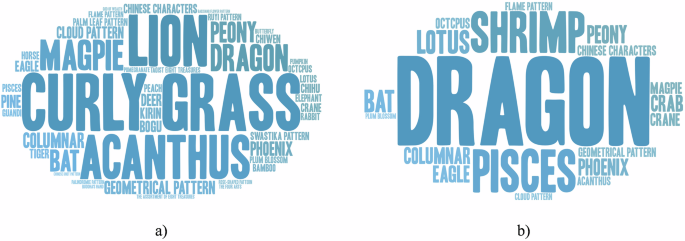

Additionally, open-ended interviews in the questionnaire and online comments revealed the frequency of tourists’ mentions of various auspicious cultural elements in both the offline photos and online comment photos. In offline comments, tourists were particularly impressed by “dragon”, “shrimp”, and “fish”, which represent Minnan traditional auspicious symbols and Nanyang auspicious elements. In the online comment photos, tourists focused on the widespread curly grasses across the village, with higher frequencies of terms like “lion”, “acanthus”, “geometrical pattern”, and “magpie”, which appeared frequently in photos of the Moral House (Western-style house), National Pride House (Fanzai buildings), and Chaodong’s Curtilage. Similarly, the “dragon”, a key auspicious cultural element, appeared most frequently in both online comments and unpublished research, reflecting its special status and symbolic significance in traditional Chinese culture (see Fig. 6).

a Pictures of auspicious elements in online comments. b Pictures of auspicious elements in offline comments. The word cloud visualizes the most frequently mentioned auspicious elements in online (left) and offline (right) tourist comments, highlighting curly grass, lion, acanthus, dragon, shrimp, and Pisces as key elements shaping tourists’ perceptions.

Wulin Village social network analysis

In terms of holistic network structure characteristics, Table 6 shows high network density and completeness in the auspicious culture, architecture space, and perceived image networks in Wulin Village. The auspicious culture network has a moderate density (0.444), reflecting the value and protection of auspicious elements. The architecture space network has a higher density (0.491), indicating a well-preserved street layout and spatial continuity. The perceived image network has the highest density (0.881), suggesting highly interconnected tourist perceptions and a comprehensive village image. Network efficiency differs: the architecture space network is the most efficient, with shorter paths and concentrated distribution supporting heritage preservation. The perceived image network is less efficient, indicating dispersed perceptions. Intermediary centrality potential values are low: architecture space (15.40%), auspicious culture (5.07%), and perceived image (0.23%) showing no clear central tendency. The auspicious culture network has a balanced distribution without dominant elements, and the architecture space network equally emphasizes buildings with well-distributed connections. The perceived image network lacks clustering around specific words, reflecting diverse perceptions. In summary, all three networks show high completeness and connectivity. The architecture space and auspicious culture networks display strong connectivity, reflecting preservation efforts. Although the perceived image network is less efficient, its diversity allows tourists to experience Wulin Village’s culture and architecture from multiple perspectives, contributing to a rich, multifaceted perception.

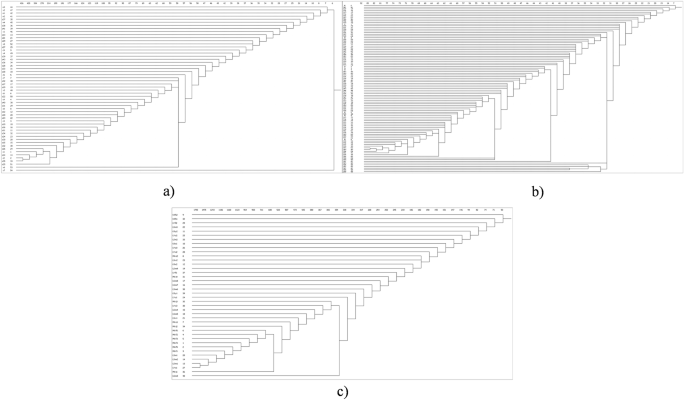

In terms of localized network structure characteristics. As shown in Fig. 7, the auspicious culture network has 47 levels of edge association, with a maximum value of 426 and a minimum of 6. This reflects stronger associations between elements of the same cultural origin, while elements from different origins co-occur less frequently. The largest cluster includes c2 (magpie) and c35 (peony), symbolizing joy and wealth, while x7 (flame pattern) appears more often alone, likely due to its Western origins. Overall, Wulin Village’s auspicious culture integrates multiple cultural elements, connecting foreign and traditional aspects. The architecture space network has 50 levels of edge correlation, with a maximum of 92 and a minimum of 7. The largest cluster includes J53 (Fanzai Buildings) and J40 (Minnan traditional house), while J6 (Minnan traditional house) forms the smallest. Minnan traditional houses, Fanzai buildings, and Western-style houses are well-integrated, though some buildings show weaker spatial connections. The perceived image network has 38 levels of edge association, with a maximum of 1793 and a minimum of 53. The largest cluster, YL-s1 (Architecture) and YS-m1 (Minnan) shows tourists most frequently associate architecture with Minnan culture. Minnan houses are the primary medium through which tourists experience the region’s culture. While “clean and tidy” influences impressions, cultural and architectural elements have a stronger impact. In conclusion, architecture in Wulin Village functions as both a physical structure and a medium for cultural transmission. Auspicious patterns, spatial design, and construction techniques shape tourists’ perceptions.

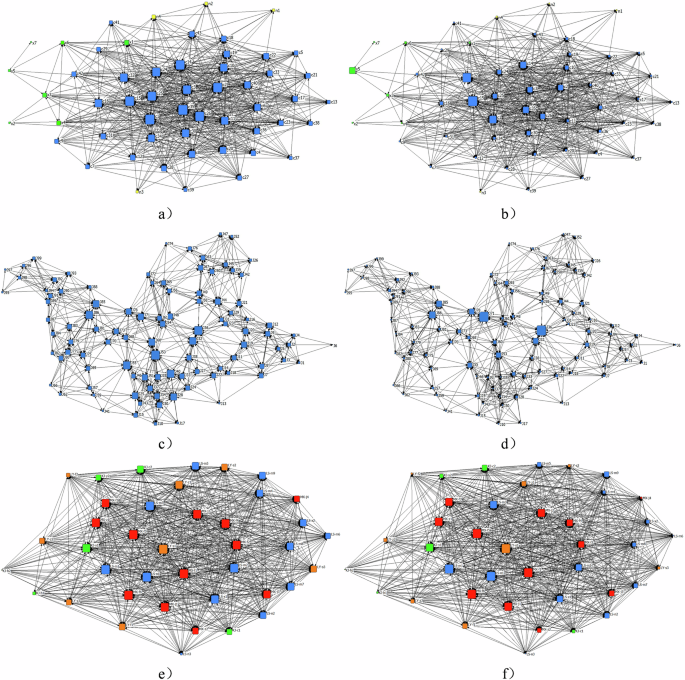

In terms of individual network structure characteristics, Fig. 8 illustrates the degree of centrality and betweenness centrality of the three networks at the individual structural level. The most influential nodes in the auspicious culture network belong primarily to traditional Minnan culture, including elements such as peony, curly grass, and plum blossom, with more controlling nodes being the Taoist eight treasures and Chinese characters. This indicates that traditional Minnan culture acts as a key intermediary in the village, facilitating the integration of foreign cultural elements. In the architecture space network, the most influential nodes are concentrated at street intersections, areas of high accessibility, and tourist gathering spots. These include traditional Minnan houses, Western-style houses, and Fanzai buildings, such as Moral House and Nanyang Cafe. In the perceived image network, nodes related to historical culture and aesthetics are highly influential. Key nodes include “traditional Minnan culture”, “overseas Nanyang culture”, and “architectural style”, underscoring the dominant role of culture and architecture in shaping tourists’ perceptions of the village. In conclusion, while Wulin Village features diverse auspicious culture and architectural styles, the most significant and influential nodes are characterized by traditional Minnan elements. This suggests that Minnan culture and traditional houses play a central role in shaping the village’s atmosphere.

a Auspicious culture betweenness centrality. b Auspicious culture degree centrality. c Architecture space betweenness centrality. d Architecture space degree centrality. e Perceived image betweenness centrality. f Perceived image degree centrality. a and b With yellow representing overseas Nanyang culture, green representing Western culture, and blue representing traditional Minnan culture. e and f Red represents esthetic characteristics, yellow represents spatial vitality, blue represents history and culture, and orange represents tourism resources. This figure presents the betweenness and degree of centrality of the auspicious culture, architecture space, and perceived image networks, identifying the most influential nodes within each network.

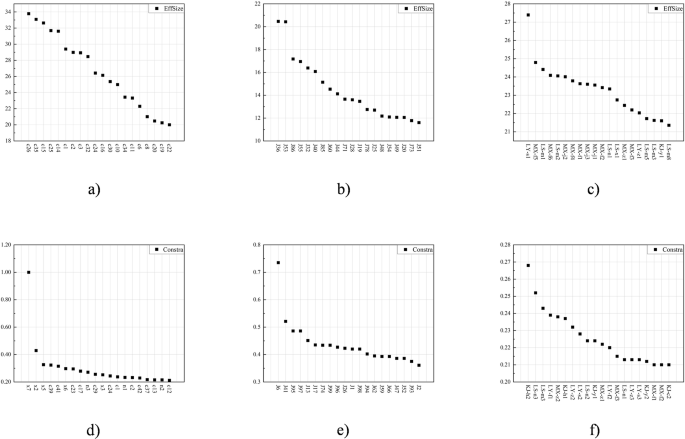

Figure 9 shows the top 20 nodes for effective size and constraint values in the auspicious culture, architecture space, and perceived image networks. Structural holes vary across the networks but are interrelated. In the auspicious culture network, the top 20 nodes with the highest effective size are all linked to traditional Minnan culture, underscoring its dominant role in cultural transmission and integration, especially with foreign cultures. In contrast, the highest constraint values are tied to Western culture, indicating fewer connections and exchanges with other cultural elements. In the architecture space network, the largest effective size nodes are J36 (Moral House) and J53 (Nanyang Cafe), located at key intersections near the village entrance with high traffic flow. Buildings with higher constraint values are in more remote areas with lower accessibility. In the perceived image network, “architectural esthetics” and “history and culture” have the largest effective size, showing that tourists’ perceptions are primarily shaped by architecture and cultural features. The highest constraint value for “cleanliness” related to the general impression of the building indicates that tourists are not particularly concerned about the village environment. Overall, while Wulin Village’s culture and architecture are diverse, traditional Minnan culture and architectural styles act as bridges for integrating foreign elements, helping tourists accept these influences while reinforcing Minnan’s cultural identity and promoting integration.

a Auspicious culture structure hole -EffSize. b Architecture space structure hole -EffSize. c Perceived image structure hole -EffSize. d Auspicious culture structure hole—Constra. e Architecture space structure hole—Constra. f Perceived image structure hole—Constra. The figure depicts structural hole analysis in auspicious culture, architecture space, and perceived image networks, illustrating effective size and constraint values that highlight key bridging elements.

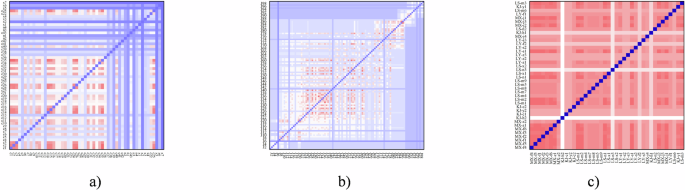

Figure 10 shows connectivity differences among the auspicious culture, architecture space, and perceived image networks in Wulin Village, revealing their structural characteristics. In the auspicious culture network, traditional Minnan culture has high connectivity, while overseas Nanyang and Western cultures show lower connectivity, suggesting traditional elements are prioritized, while foreign influences are peripheral. The architecture space network shows connectivity ranging from 4 to 8, reflecting building interdependence and spatial clustering, particularly in the core conservation area. J36 (Moral House) stands out with high connectivity, emphasizing its central role. The perceived image network shows high connectivity, particularly in the sub-themes of “architectural style” and “Minnan culture” and in the theme of “architectural style”, indicating these are key focus areas for tourists. While auspicious culture is important, its architectural decorations are perceived less strongly compared to style and color, likely due to their less prominent visual presence. Improving the presentation of auspicious culture can enhance tourist engagement and understanding of traditional cultural elements.

a Auspicious culture point connectivity. The image displays a color scale for “Point Connectivity,” with the following range of values: The highest value, 43.00, is represented by a deep red color. The values gradually decrease, transitioning through shades of pink to light blue. The lowest value, 0.000, is represented by a deep blue color. b Architecture space point connectivity. The image displays a color scale for “Point Connectivity,” with the following range of values: The highest value, 21.00, is represented by a deep red color. The values gradually decrease, transitioning through shades of pink to light blue. The lowest value, 0.000, is represented by a deep blue color. c Perceived image point connectivity. The image displays a color scale for “Point Connectivity,” with the following range of values: The highest value, 39.00, is represented by a deep red color. The values gradually decrease, transitioning through shades of pink to light blue. The lowest value, 3.00, is represented by a deep blue color.

Correlation between auspicious culture, architecture space, and perceived image of Wulin Village

Table 7 demonstrates a significant correlation between auspicious culture, architecture space, and perceived image. The significant correlation between auspicious culture and architectural space. Most of the auspicious patterns on Wulin Village’s traditional alcoves originate from traditional Minnan culture, while the Fanzai buildings integrate elements of both Minnan and overseas Nanyang culture, and the auspicious patterns on Western-style houses are primarily derived from Western culture. Additionally, in nodes with high centrality in both the auspicious cultural network and the architecture space network, traditional Minnan culture occupies a central position, and the Minnan traditional houses are located in core areas. This alignment underscores the strong correspondence and high correlation between the auspicious cultural network and the architecture space network in Wulin Village. Together, the architectural spatial structure and auspicious culture shape tourists’ perceptual experience, emphasizing the importance of both cultural heritage and village identity.

There is a significant correlation between auspicious culture and perceived image, highlighting the importance of protecting and promoting auspicious culture to shape tourists’ perceptions. While tourists’ perception of auspicious cultural elements in online texts is limited, a combination of online comment photos and offline comment photos reveals that tourists do have notable perceptions, particularly of traditional Minnan auspicious elements. According to the statistics of photos uploaded by tourists’ online comments, the top 5 photos of auspicious cultural elements taken by tourists are Curly grass (53.03%), Lion (31.27%), Acanthus (31.15%), Geometrical pattern (25.96%) and Magpie (24.72%) (see Fig. 11). However, the auspicious cultural elements of the dragon (23.61%) should not be overlooked. This connection is rooted in the historical symbolism of the dragon, a central figure in Chinese culture. For local tourists, the dragon symbolizes wealth, enhancing their cultural identity and pride. For tourists from other regions of China, its mystery and auspiciousness attract attention and deepen their understanding of Wulin Village’s unique culture Furthermore, tourists’ impressions of Minnan culture are significantly stronger than those of foreign Nanyang and Western cultures in online comments, underscoring the connection between auspicious culture and perceived image. However, certain auspicious cultural elements, such as exotic Nanyang and Western-style auspicious patterns, are still inadequately preserved and inherited. This highlights the need to strengthen the revitalization of these auspicious patterns to better protect and enhance the multicultural heritage (see Fig. 11).

A significant correlation exists between architectural space and perceived image. The centrality, scale, and high-connectivity nodes of the architecture space network align closely with tourists’ perceptions. Key nodes, such as Moral House and Nanyang Cafe, along with nearby traditional residential areas, enhance tourists’ understanding of architectural functions, styles, and history. Located at key intersections and along main tour routes, these nodes hold importance in both the spatial structure and tourists’ perceived image due to their cultural and historical significance. This suggests that prominent architectural nodes not only define physical space but also play a crucial role in shaping the cultural experience of tourists, highlighting the strong influence of architectural space on perceived image. Understanding this relationship provides a scientific basis for utilizing these spatial nodes to enrich tourists’ cultural experiences in future village planning and heritage promotion.

Discussion

There is an interactive mechanism present in the architectural space, auspicious culture, and perceived image of Wulin Village. The sociology of space posits that space is shaped by social relations and significantly influences behavior and perception51. In Wulin Village, the design and layout of architectural spaces reflect the signs and symbolism of auspicious culture, which in turn affects tourists’ emotional and cognitive responses through visual and sensory stimuli52. Cultural semiotics further highlight that the presentation of auspicious cultural elements through architecture evokes emotional resonance in tourists, enhancing their sense of identity and satisfaction with the area53. Specifically, elements such as color, pattern, and spatial form in architecture trigger associations with auspicious culture, influencing tourists’ emotional reactions and cognitive evaluations of the site. These mechanisms collectively shape the overall perception and experience of the scenic spot.

In exploring the characteristics and interaction mechanisms among architectural space, auspicious culture, and perceived image in Wulin Village, the study finds that the auspicious cultural network demonstrates moderate network efficiency and a balanced distribution of nodes at the overall structural level. From the perspective of individual structural features, traditional Minnan auspicious cultural elements exhibit the highest connectivity. This structural characteristic indicates that both residents and outside tourists predominantly perceive culture through traditional Minnan culture. At the same time, foreign cultural elements play a supplementary role, enriching tourists’ cultural experiences and expanding their understanding. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of Pennington and colleagues in their study of Florida, USA, where they noted that tourists are more likely to accept cultural symbols and markers aligned with their cultural backgrounds54. At the same time, the integration of foreign cultural elements can help broaden cultural understanding and enhance overall perception. Similarly, Vinnikov’s study on the perception of architectural decorations in Roman churches found that tourists tend to pay greater attention to symbolic cultural elements closely related to the specific environment in which they are situated, highlighting the influence of cultural proximity on perception55. Deng and colleagues, through a study of visual characteristics in architectural cultural elements in Xiamen, China, also found that tourists from various cultural backgrounds can generally recognize and interpret traditional patterns and cultural symbols through visual means56. Notably, local tourists demonstrate a deeper perception of traditional culture. In summary, the culturally networked structure of Wulin Village—dominated by local culture and supplemented by foreign elements—not only strengthens the foundation of the village’s cultural identity but also provides strong support for enriching tourists’ multicultural perceptions.

In the context of architecture space networks, research has shown that tourists’ perception of space is influenced by multiple factors, including socio-cultural background, spatial organization, and architectural functions. Golledge pointed out that people’s spatial perception is closely related to their cultural environment and the intended use of buildings, a phenomenon that is particularly evident in the architectural space network of Wulin Village57. This network demonstrates strong overall integrity and stability, with well-connected nodes. The study finds that the Moral House, due to its high connectivity and accessibility, emerges as a key node within the network and is also one of the most memorable areas for tourists. Moreover, as a primary venue for residents to hold public activities and traditional festivals, the Moral House has naturally become a core gathering space for the local community. Sun and colleagues, in their study of three representative villages in Shanxi Province, China, found that public cultural spaces with higher accessibility serve as key sites for frequent interaction between residents and tourists58. Additionally, the cultural attributes of these spaces significantly enhance individuals’ perception of the village’s spatial and traditional cultural characteristics. This finding is further supported by Askarizad et al., whose empirical study of historical and cultural districts in Iran reveals that tourists are more likely to form deep impressions of iconic architectural spaces that possess historical significance and local cultural features-especially when these spaces are highly accessible, leading to stronger collective perception59. Tuncer and Ramadier through their respective studies in Turkey and France, further demonstrate that tourists’ architectural perception is not only shaped by their familial and ethnic backgrounds but also enhanced by exposure to buildings with multicultural characteristics60,61. Moreover, architectural nodes located in areas of high accessibility and centrality significantly improve the clarity of tourists’ spatial understanding.

In the perceived image network, the Wulin Village has the strongest integrity of the perceptual image network and has a wide distribution of nodes. At the same time, studies have shown that tourists perceive culture and architectural styles through various means, among which visual observation of buildings and recognition of their styles serve as the primary approach to enhancing cultural understanding. Nguyen’s research pointed out that in Hong Kong, China, tourists can perceive local cultural information embodied in architectural styles and construction techniques by observing local architectural heritage sites62. Zhang and colleagues, in an empirical study on Korean heritage villages, found that tourists primarily gain an understanding of village architecture through on-site visits and visual experiences63. In doing so, they not only perceive the historical traditions and architectural landscapes but also deepen their appreciation of traditional cultural values. Similarly, Kusno, in his research on architectural spaces in Southeast Asia, noted that the interaction between architectural style and local historical context collectively shapes tourists’ cultural memory of the overall spatial environment64.

Previous studies have primarily focused on the relationships between auspicious culture and perceived image, auspicious culture and architectural space, as well as architectural space and perceived image, while relatively little attention has been paid to the integrated relationship among architectural space, auspicious culture, and perceived image65,66,67,68. This study explores how architectural space and auspicious culture shape tourists’ perceptions within the context of traditional village heritage. Our findings indicate that architectural style is the primary factor influencing tourists’ impressions, while auspicious culture enhances the perception of tourists through its integration with architectural space45,69. Among various landscape elements, architectural style exhibits characteristics such as coherence, fascination, and hominess. Compared with auspicious patterns that embody deep cultural meanings, tourists in unfamiliar environments are more likely to focus on architectural style70. Although Auspicious cultural elements carry significant symbolic meaning; they are generally smaller in size and exhibit diverse forms, often attached to architectural structures, whereas architectural styles tend to present a consistent overall appearance71. In the global tourism market, cultural experience and emotional engagement are key drivers in attracting tourists. The three-dimensional model developed in this study integrates material, cultural, and perceptual dimensions, offering a comprehensive understanding of Wulin Village’s cultural heritage from both objective and subjective perspectives. This model provides a scientific framework for evaluating how cultural factors are communicated and holds significant implications for the sustainable development of heritage and tourism in culturally and historically rich regions worldwide. Not only does this model play an important role in the cultural heritage preservation and tourism development of Wulin Village, but it also possesses strong potential for international application. As global demand for cultural experiences continues to grow, this model offers a theoretical framework that can guide cultural heritage management and tourism development in other culturally rich regions, thereby promoting the sustainable development of global cultural tourism.

In terms of the strategies for the revitalization and inheritance of the cultural heritage of Wulin Village, the study reveals a significant correlation between auspicious culture and the perceived image of Wulin Village, which has a positive effect on the revitalization and inheritance strategy of Wulin Village cultural heritage72,73. Tourists’ perception of auspicious cultural elements is affected by personal background and cultural attributes, and those regional and typical cultural elements are not only easy for tourists to identify but also stimulate their associations and memories, thus enhancing their sense of identity and belonging74. Therefore, corresponding heritage protection and tourism strategies can be formulated according to tourists’ perceived preferences. Although tourists often overlook architectural decorations and auspicious patterns, their sense of identity and belonging is strengthened by symbolic cultural elements. Current development strategies fail to adequately protect and highlight these non-renewable cultural heritages, which are esthetically, culturally, and socially significant, reflecting the diverse traditions of Minnan. Future strategies should prioritize the preservation and promotion of auspicious culture. First, key cultural elements such as the “dragon”, “shrimp”, and “magpie” should be highlighted at road intersections. A central cultural gallery could showcase auspicious patterns, symbols, and craftsmanship to enhance cultural confidence and visibility. Second, auspicious culture should be integrated into tourism route design. Developing four thematic cultural routes-“Minnan Traditional Auspicious Culture”, “Overseas Nanyang Auspicious Culture”, “Western Auspicious Culture”, and “Diversified Auspicious Culture”-would deepen tourists’ understanding and appreciation of Wulin Village’s cultural heritage. Revitalizing Wulin Village’s cultural heritage requires an integrated approach to architectural and cultural preservation, respecting regional differences. A diverse strategy for heritage revitalization is key to ensuring sustainable development (see Fig. 12).

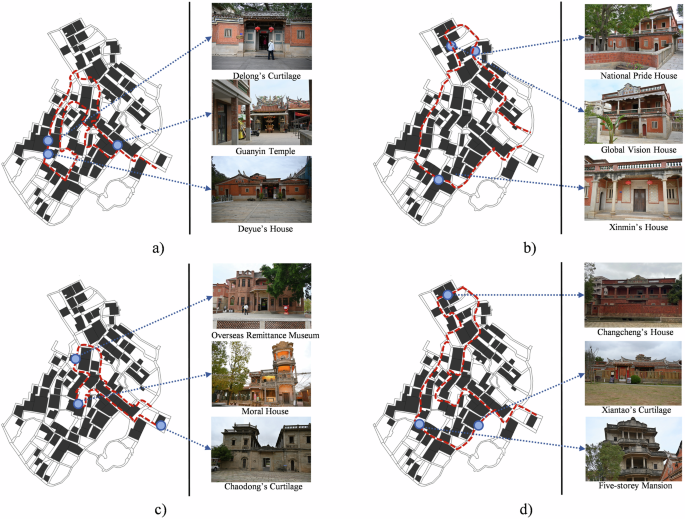

a Traditional Minnan auspicious culture route. b Overseas Nanyang auspicious culture route. c Western Auspicious Culture route. d Diversified Auspicious Culture route. The figure illustrates four thematic cultural heritage routes in Wulin Village, highlighting Traditional Minnan, Overseas Nanyang, Western, and Diversified Auspicious Culture routes, with key landmarks along each path.

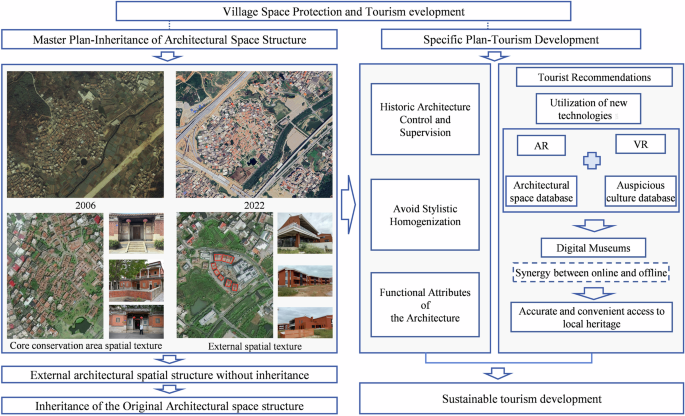

In terms of the spatial conservation and tourism development strategy of Wulin Village, the association of tourists’ perceived image and architecture networks has important applications for village spatial conservation and tourism development. The current study reveals that Wulin Village follows a “natural growth” spatial pattern, reflecting the ancient Minnan people’s wisdom in balancing yin and yang and harmonizing with the landscape. Combining these findings with tourist feedback from the questionnaire, we observe that while the core conservation area retains well-preserved traditional buildings, the external area suffers from a lack of planning due to self-construction and relocation. This disconnect has led to functional homogenization and reduced decorative diversity, undermining the continuity of the traditional Minnan layout and auspicious culture. To address these issues, new buildings should harmonize with the core area, and tourism development must be carefully managed to maintain balance within the protected zone. Additionally, leveraging new technologies such as VR and AR, along with a comprehensive architecture space and auspicious culture database, can facilitate the creation of a digital museum. (1) A virtual model of Wulin Village is created, allowing tourists to explore architectural relics, auspicious elements, street spaces, and other cultural heritage in a panoramic view, all without visiting the site. (2) During the on-site tour, tourists can use an AR application to view auspicious patterns (e.g., dragons, bats, shrimps) on the buildings and learn about their historical and cultural significance. (3) An online digital museum focuses on the village’s traditional architecture, decorative patterns, and folk culture. It features interactive displays and a database, allowing tourists to explore detailed information by touching or clicking the screen, thereby deepening their understanding and engagement with local culture. This would allow both Chinese and international tourists to quickly and accurately explore the architectural styles and auspicious cultural elements online. In conclusion, combining traditional preservation methods with advanced technologies will enhance the dissemination and promotion of Wulin Village’s cultural heritage, supporting its revitalization and offering a richer tourism experience (see Fig. 13). In many regions, particularly those undergoing rapid urbanization or experiencing significant foreign cultural influences, reinforcing cultural perceptions has become a critical issue for heritage conservation and development. By applying the innovative method of social network analysis, this study quantitatively examines the spatial structure and cultural elements, revealing the deep-rooted connections between spatial texture and auspicious culture. This approach not only helps strengthen residents’ sense of belonging and cultural identity but also enhances their cultural confidence and the competitiveness of heritage tourism in the context of globalization.

This framework outlines village space protection, architectural heritage conservation, and tourism development strategies, integrating digital technology (AR/VR), architectural databases, and digital museums to enhance cultural sustainability. Questionnaire on Perception of Auspicious Cultural Elements in Wulin Village.

In conclusion, this study analyzes the interactive relationships among auspicious culture, architectural space, and tourists’ perceived image of Wulin Village, and proposes a series of strategies to promote the sustainable development of heritage. The main findings are as follows: (1) In the auspicious culture network, although there are numerous auspicious elements, tourists show stronger perceptions of tangible, traditional Minnan auspicious symbols. This suggests that tourists possess a strong emotional connection and cognitive foundation toward traditional Chinese culture. Elements such as the “dragon”, “bat”, and “plum blossom”, which carry clear symbolic meanings and rich cultural connotations, help shape tourists’ initial impressions of Wulin Village’s auspicious culture. (2) In the architectural space network, the structure is stable and balanced, with core nodes that hold both transportation and cultural value. As a result, tourists tend to spend more time and engage more frequently in these areas, allowing them to efficiently access and perceive the cultural significance embedded in architectural space, which in turn influences their overall perception of the village. (3) In the perceived image network, the network exhibits the highest density but the lowest efficiency. This reflects the need for better organization of tour routes in Wulin Village. Although tourists’ perceptions are diverse, architecture and culture remain dominant themes. This indicates that Wulin Village has notable strengths in cultural preservation and architectural heritage, and highlights the need to further emphasize these elements when optimizing tourist routes and enhancing the tourist experience. (4) There are significant pairwise correlations among the auspicious culture, architectural space, and perceived image networks, indicating strong interrelationships and mutual influences among these factors. Specifically: (a) The significant correlation between auspicious culture and architectural space reveals a deep level of integration. Architectural spaces serve as important carriers of auspicious culture by incorporating symbolic elements into design and decoration, enabling tourists to experience the charm and meaning of auspicious culture while engaging with the built environment. (b) The significant correlation between auspicious culture and perceived image reflects the important role that auspicious elements play in shaping tourists’ perceptions of Wulin Village. These elements evoke emotional resonance and cultural identity, thereby influencing how tourists perceive and evaluate the village as a whole. (c) The significant correlation between architectural space and perceived image suggests that tourists’ overall impressions and perception evaluations of Wulin Village are largely influenced by the layout and organization of its architectural spaces. These spaces not only function as physical environments but also carry rich cultural and historical significance, jointly shaping the perceived image of the village. This interrelated structure demonstrates that auspicious culture, architectural space, and perceived image form an organic whole, influencing and reinforcing each other to collectively shape tourists’ experiences and perceptions in Wulin Village.

The innovation of this study lies in the construction of a three-dimensional network model of “Architectural Space–Auspicious Culture–Perceived Image”, which breaks through the limitations of traditional tourism perception assessment methods. By quantifying the interrelationships among space, culture, and perception, this model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding tourists’ multidimensional perceptual experiences. It not only identifies priority areas for the conservation and planning of Wulin Village but also offers valuable insights into the dynamic protection of historical heritage. Moreover, the differences in tourists’ online and offline perceptions of auspicious cultural elements provide a practical reference for the preservation of these elements in the village. Firstly, symbolic elements that attract strong tourist interest, such as the “dragon” and “bat, “ can be prioritized in preservation efforts or incorporated into cultural heritage projects to enhance cultural education and dissemination. Through online platforms, social media, and cultural exchange activities targeting international audiences, the visibility and recognition of Wulin Village’s auspicious culture can be further promoted. Secondly, cultural events and exhibitions can be organized to deepen tourists’ participation, allowing them to gain a more immersive understanding of auspicious culture and enhancing their sense of cultural identity and engagement. Lastly, based on the spatial distribution of architectural features and auspicious cultural elements, themed cultural tourism routes can be designed. Each route may highlight architectural characteristics, cultural activities, or historical narratives to help tourists explore the cultural background in depth. Furthermore, this three-dimensional model possesses strong international relevance and cross-cultural applicability, offering a novel methodology for global research in cultural heritage and tourism. By applying this framework, researchers and heritage managers can analyze the transmission paths of cultural symbols, thereby promoting effective protection and sustainable development of cultural heritage worldwide.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample is limited to Wulin Village. Future research should expand to include other tourist destinations, compare different types of cultures, and take into account tourists’ social backgrounds, age preferences, gender, and occupations to better understand “cultural perception” in traditional villages with diverse historical and ethnic contexts. Secondly, due to the lack of historical data on traditional villages, this study provides only a current-period analysis and lacks a dynamic perspective on the village network. Future research should build on this data foundation to explore tourists’ dynamic spatial preferences, emotional tendencies, and perceptual changes, to further uncover the factors influencing cultural perception. Finally, since the preservation and development of auspicious patterns in Wulin Village is an ongoing process, the current data analysis may contain certain biases. Future studies should address this issue through continuous monitoring to achieve greater accuracy and scientific validity.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

-

Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: from the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 11, 321–324 (2010).

-

Bak, S., Min, C.-K. & Roh, T.-S. Impacts of UNESCO-listed tangible and intangible heritages on tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 36, 917–927 (2019).

-

Porretta, P., Pallottino, E. & Colafranceschi, E. Minnan and Hakka Tulou. Functional, typological and construction features of the rammed earth dwellings of Fujian (China). Int. J. Archit. Herit. 16, 899–922 (2022).

-

Zhang, S., Liang, J., Su, X., Chen, Y. & Wei, Q. Research on global cultural heritage tourism based on bibliometric analysis. Herit. Sci. 11, 139 (2023).

-

Qu, Y. et al. Geographic identification, spatial differentiation, and formation mechanism of multifunction of rural settlements: a case study of 804 typical villages in Shandong Province, China. J. Clean. Prod. 166, 1202–1215 (2017).

-

Qiu, H. et al. Research on intelligent monitoring technology for roof damage of traditional Chinese residential buildings based on improved YOLOv8: taking ancient villages in southern Fujian as an example. Herit. Sci. 12, 231 (2024).

-

Kamada, M. & Nakagoshi, N. Influence of cultural factors on landscapes of mountainous farm villages in western Japan. Landsc. Urban Plan. 37, 85–90 (1997).

-

Cassidy, L. & Barnes GD. Understanding household connectivity and resilience in marginal rural communities through social network analysis in the village of Habu, Botswana. Ecol. Soc. 17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269205 (2012).

-

Dai, L., Sheng, X. & Gupta, R. Socio-spatial features of neighbourhoods supporting social interaction between locals and migrants in peri-urban China. J. Urban Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2024.07.006 (2024).

-

Fang, S., Zhao, Y., Liu, X. & Yang, Y. Quantitative characteristics and influencing factors of Tibetan Buddhist religious space with monasteries as the carrier: a case study of U-Tsang, China. Herit. Sci. 12, 93 (2024).

-

Nancarrow, J.-H., Yang, C. & Yang, J. An emotions-informed approach for digital documentation of rural heritage landscapes: Baojiatun, a traditional tunpu village in Guizhou, China. Built Herit. 5, 11 (2021).

-

Mitchell JC. Social networks. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 3, 279–99. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2949292 (1974).

-

Freeman, L. The development of social network analysis. A Study Sociol Sci 1, 159–167 (2004).

-

Wang, Y., Li, X. & Lai, K. A meeting of the minds: exploring the core–periphery structure and retrieval paths of destination image using social network analysis. J. Travel Res. 57, 612–626 (2018).

-

Dempwolf, C. S. & Lyles, L. W. The uses of social network analysis in planning: a review of the literature. J. Plan. Lit. 27, 3–21 (2012).

-

Wei, D., Wang, Z. & Zhang, B. Traditional village landscape integration based on social network analysis: a case study of the Yuan river basin in south-western China. Sustainability 13, 13319 (2021).

-

Bennett, T. Making culture, changing society: the perspective of ‘culture studies. Cult. Stud. 21, 610–629 (2007).

-

Zhong, C., Arisona, S. M., Huang, X., Batty, M. & Schmitt, G. Detecting the dynamics of urban structure through spatial network analysis. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 28, 2178–2199 (2014).

-

Zhang, P. et al. Spatial structure of urban agglomeration under the impact of high-speed railway construction: based on the social network analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 62, 102404 (2020).

-

Huang, Y., Li, L. & Yu, Y. Do urban agglomerations outperform non-agglomerations? A new perspective on exploring the eco-efficiency of Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. J. Clean. Prod. 202, 1056–1067 (2018).

-

Zeng, X., Ma, Y., Ren, J. & He, B. Assessing the network characteristics and structural effects of eco-efficiency: a case study in the urban agglomerations in the middle reaches of Yangtze River, China. Ecol. Indic. 150, 110169 (2023).

-

Hui, E. C., Li, X., Chen, T. & Lang, W. Deciphering the spatial structure of China’s megacity region: a new bay area—the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area in the making. Cities 105, 102168 (2020).

-

Jiang, B., Duan, Y., Lu, F., Yang, T. & Zhao, J. Topological structure of urban street networks from the perspective of degree correlations. Environ. Plan. B: Plan. Des. 41, 813–828 (2014).

-

Zhang, B., Fan, J., Zhang, P., Shen, S. & Ren, Y. The Changsha historic urban area: a study on the evolution characteristics and influencing factors of the connectivity of construction land. Herit. Sci. 12, 287 (2024).

-

Daraganova, G. et al. Networks and geography: modelling community network structures as the outcome of both spatial and network processes. Soc. Netw. 34, 6–17 (2012).

-

Porta, S., Crucitti, P. & Latora, V. The network analysis of urban streets: a dual approach. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 369, 853–866 (2006).

-

Liu, Y., Li, Z. & Breitung, W. The social networks of new-generation migrants in China’s urbanized villages: a case study of Guangzhou. Habitat Int. 36, 192–200 (2012).

-

Verdery, A. M., Entwisle, B., Faust, K. & Rindfuss, R. R. Social and spatial networks: Kinship distance and dwelling unit proximity in rural Thailand. Soc. Netw. 34, 112–127 (2012).

-

Todd, N. R., Blevins, E. J. & Yi, J. A social network analysis of friendship and spiritual support in a religious congregation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 65, 107–124 (2020).

-

Tian, Y., Kong, X., Liu, Y. & Wang, H. Restructuring rural settlements based on an analysis of inter-village social connections: a case in Hubei Province, Central China. Habitat Int. 57, 121–131 (2016).

-

Qi, L., Wang, Y., Chen, J., Liao, M. & Zhang, J. Culture under complex perspective: a classification for traditional Chinese cultural elements based on NLP and complex networks. Complexity 2021, 6693753 (2021).

-

Stepchenkova, S., Kim, H. & Kirilenko, A. Cultural differences in pictorial destination images: Russia through the camera lenses of American and Korean tourists. J. Travel Res. 54, 758–773 (2015).

-

Beerli, A. & Martin, J. D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 31, 657–681 (2004).

-

Baloglu, S. & McCleary, K. W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 26, 868–897 (1999).

-

Choi, S., Lehto, X. Y. & Morrison, A. M. Destination image representation on the web: content analysis of Macau travel related websites. Tour. Manag. 28, 118–129 (2007).

-

Gartner W. Tourism Development: Principles, Processes, and Policies (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996).

-

Xiao, X., Fang, C. & Lin, H. Characterizing tourism destination image using photos’ visual content. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 9, 730 (2020).

-

McCartney, G. Does one culture all think the same? An investigation of destination image perceptions from several origins. Tour. Rev. 63, 13–26 (2008).

-

Lin, C.-H., Morais, D. B., Kerstetter, D. L. & Hou, J.-S. Examining the role of cognitive and affective image in predicting choice across natural, developed, and theme-park destinations. J. Travel Res. 46, 183–194 (2007).

-

Basaran, U. Examining the relationships of cognitive, affective, and conative destination image: a research on Safranbolu, Turkey. Int. Bus. Res. 9, 164–179 (2016).

-

Kim, S.-E., Lee, K. Y., Shin, S. I. & Yang, S.-B. Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: the case of Sina Weibo. Inf. Manag. 54, 687–702 (2017).

-

Pan, X., Rasouli, S. & Timmermans, H. Investigating tourist destination choice: Effect of destination image from social network members. Tour. Manag. 83, 104217 (2021).

-

Kang, N. & Liu, C. Assessment of visual quality and social perception of cultural landscapes: application to Anyi traditional villages, China. Herit. Sci. 12, 235 (2024).

-

Taecharungroj, V. & Mathayomchan, B. Analysing TripAdvisor reviews of tourist attractions in Phuket, Thailand. Tour. Manag. 75, 550–568 (2019).

-

Zhao, H., Huang, Z., Deng, C. & Ren, Y. The decorative auspicious elements of traditional Bai Architecture in Shaxi Ancient Town, China. Sustainability 15, 1918 (2023).

-

Hillier, B. Space is the Machine: a Configurational Theory of Architecture: Space Syntax (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2007).

-

Li, H., An, H., Wang, Y., Huang, J. & Gao, X. Evolutionary features of academic articles co-keyword network and keywords co-occurrence network: based on two-mode affiliation network. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 450, 657–669 (2016).

-

Liu, R. & Xiao, J. Factors affecting users’ satisfaction with urban parks through online comments data: evidence from Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 253 (2021).

-

Kirilenko, A. P. & Stepchenkova, S. Inter-coder agreement in one-to-many classification: fuzzy kappa. PLoS ONE 11, e0149787 (2016).

-

Carletta, J. Assessing agreement on classification tasks: the kappa statistic. Comput Linguist. 22, 249–54 (1996).

-

Lefebvre H. From the production of space. In Theatre and Performance Design (eds Davey J & Chamier J) 81–84 (Routledge, 2012).

-

King A. Spaces of Global Cultures: Architecture, Urbanism, Identity (Routledge, 2004).

-

Umiker-Sebeok, D. J. Semiotics of culture: Great Britain and North America. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 6, 121–135 (1977).

-

Pennington, J. W. & Thomsen, R. C. A semiotic model of destination representations applied to cultural and heritage tourism marketing. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 10, 33–53 (2010).

-

Vinnikov, M., Motahari, K., Hamilton, L. I. & Altin, B. O. (eds) Understanding Urban Devotion through the Eyes of an Observer. ACM Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications (ACM, 2021).

-

Deng, J., Chen, J. & Lei, Y. A study on the visual perception of cultural value characteristics of traditional southern Fujian architecture based on eye tracking. Buildings 14, 3529 (2024).

-

Golledge, R. G. Geographical perspectives on spatial cognition. In Advances in Psychology Vol. 96, 16–46 (Elsevier, 1993).

-

Sun, C. & Lee, I. Cognitive recognition of space and social connections of traditional villages in Shanxi Province: a case study of Ding, Shijiagou, and Yanjing Villages. Sustainability 16, 9695 (2024).

-

Askarizad, R. & He, J. Perception of spatial legibility and its association with human mobility patterns: an empirical assessment of the historical districts in rasht, iran. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 15258 (2022).

-

Tuncer, E. editor Perception and intelligibility in the context of spatial syntax and spatial cognition. In Proc. of the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium, İstanbul (eds Kubat, A. S., Ertekin, O., Guney. Y. l, Eyuboglu, E. E.,) (Istanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, 2007).

-

Ramadier, T. & Moser, G. Social legibility, the cognitive map and urban behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 18, 307–319 (1998).

-