Jenny Saville, the Body Artist

In March, an exhibition of works by Jenny Saville, the British artist known for her large-scale figurative paintings, went on display at the Albertina Museum, in Vienna. The day before the opening, Saville visited the galleries to inspect the completed hang. The show, titled “Gaze,” included several works in which Saville had sought to explore the fractured experience of life in the digital era. “I have had a fascination for quite a while now with how we live these different realities,” she explained. “If you sit on a bus or take the subway, everybody’s on a device. So you’ve got this sort of mundane, lived reality, and then this screened reality. If you’ve got twenty people on the subway train, those twenty people are probably all over the globe, or even in outer space. Those realities exist all the time. You just move in and out, seemingly seamlessly.”

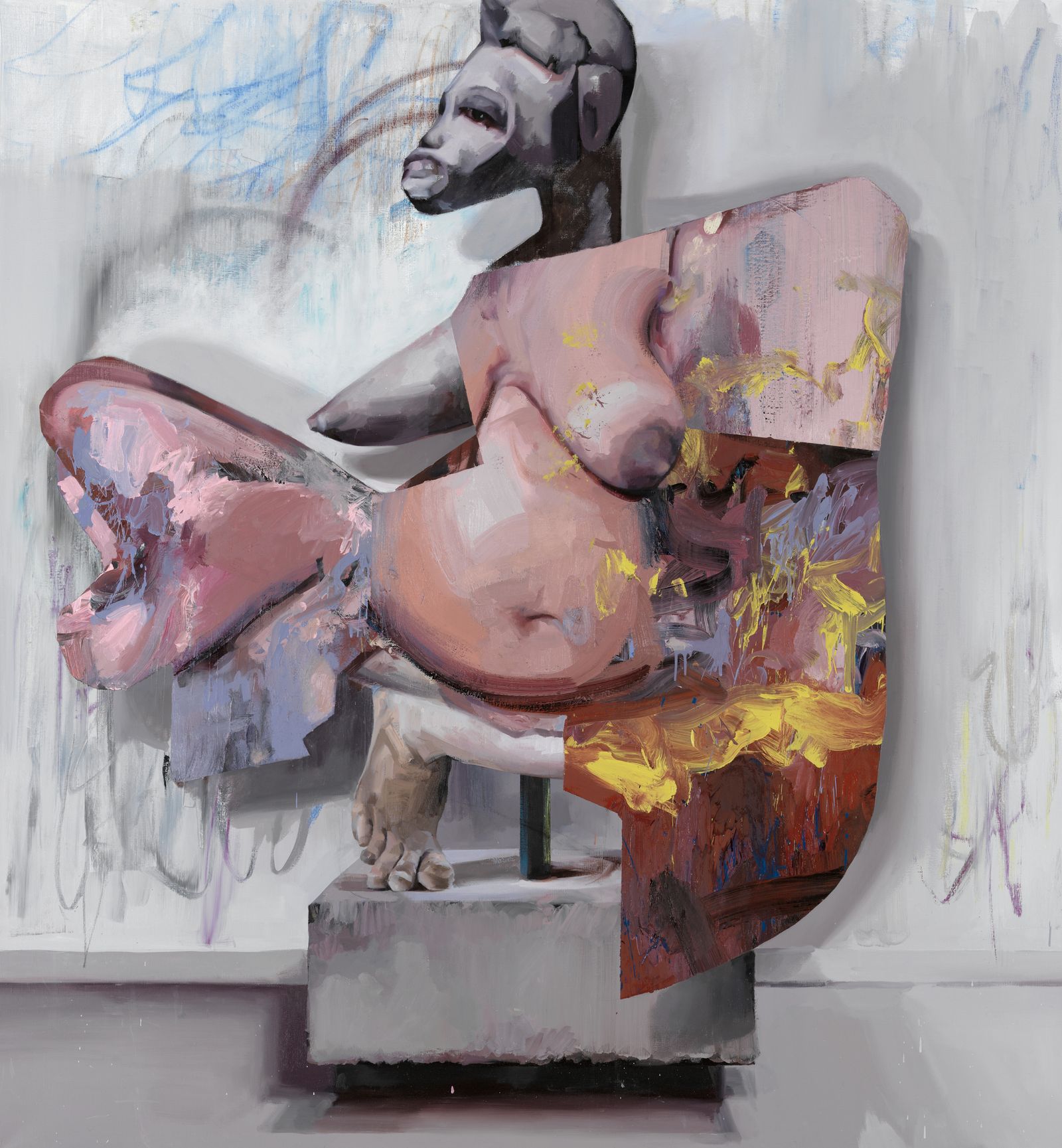

We looked at a series of three paintings, titled “Fates.” Each depicted a woman seated in a chair mounted on a stone plinth. They had been completed in 2018, and at the time, Saville told me, she “had been looking at images of ancient goddesses.” The figures had the monumentality of classical sculpture, but they lacked the corporal integrity expected from such forms. In “Fate 2,” the figure sat with her right leg cocked, her foot balanced on the opposite knee—but there was also a third leg, which hung over the arm of the chair. The figure’s midsection was scrambled into colored marks, a belly button indicated by a scrawl of black on pink. “Fate 3” also depicted a female body, but with a pregnant belly and pendulous breasts, her intimidating scale exaggerated by the viewer’s lowered vantage point. A pair of legs was tucked beneath her, while a third haunch and leg extended to her right. The surfeit of limbs suggested the temporal and spatial layering of experience which has become central to the way we see and live today. The “Fate” paintings conveyed an impulse toward motion, capturing the restlessness inherent in a human body—particularly a body that is building up the flesh and blood and bone of another body within its own. The paintings offered technically accomplished realism—Saville can paint a puckered nipple so lifelike that it makes you want to turn up the heat—combined with gestural abstraction. Her female figures were large in their art-historical scope as well as in their scale, evoking not just the classical tradition but also canonical modernist works by Pablo Picasso and Willem de Kooning.

At the same time, the paintings reached back visually into Saville’s own catalogue. Now fifty-five, she achieved acclaim when she was in her early twenties for another series of paintings focussing on the female body, some of which she made while still an undergraduate, at the Glasgow School of Art. She had been precocious in her painterly virtuosity, particularly in the depiction of human flesh, with its mottled colors and variable textures, the swell of muscle and the yielding dimples of fat. Among these early works was “Propped” (1992), a seven-foot-by-six-foot canvas on which Saville had depicted a towering female nude perched atop a stool, her legs wrapped around a pedestal-like base. The figure’s ample bosom poured forth, but it was not the painting’s focal point; the viewer’s eye was drawn instead to meaty, jutting knees and sturdy thighs, into which were dug tensed, strong fingers. “Propped” had been the centerpiece of Saville’s graduation exhibition, where it was displayed opposite a mirror. In the reflection, an onlooker could read words by Luce Irigaray, the French feminist philosopher, which Saville had etched, in reverse, into the oil paint with the tip of a brush: “If we continue to speak in this sameness—speak as men have spoken for centuries, we will fail each other.”

Not long after Saville’s student show, the London Times Saturday Review published an article about emerging British artists and included a photograph of “Propped,” before which stood its comparatively diminutive creator. (Her work was characterized as “breathtakingly accomplished,” with “a fierce feminist message.”) The painting caught the eye of Charles Saatchi, at the time the most prominent collector of contemporary art in Britain. He swiftly acquired it, along with several of Saville’s other student works, and also provided funding to support her for a year and a half while she made paintings for her first solo gallery show, in January, 1994.

In these and many subsequent works, Saville took on one of the principal themes of Western art since the Renaissance: the naked female form. But she represented it in a manner that had never quite been seen before. Unlike the works of Rubens or Rembrandt or Lucian Freud, all of whose influences on Saville were clear, her paintings showed what it was like to occupy a female body, rather than to appraise it from an easel. Saville was her own model for “Propped,” and early interviewers were surprised to discover that she was, and remains, a compactly built woman—the imposing scale of the painting was a trick of perspective.

Some critics found Saville’s approach off-putting: a male interviewer for the Independent questioned why her depictions of women seemed intent on “making them look so horrible.” “I’m not painting disgusting, big women. I’m painting women who’ve been made to think they are big and disgusting,” Saville told him, her point having been proved. Others were more nuanced in their reactions. In 1994, the critic Sarah Kent wrote an assessment of “Branded” (1992), in which a large female nude grasps a roll of belly fat in what Kent notes could be a gesture of defiance, or of self-loathing. Across the figure’s flesh, Saville had scrawled various words, including “supportive,” “decorative,” and “irrational.” The figure, Kent wrote, “is occupied by an intelligence that makes us ashamed at our responses, and dismayed at our shame.” Kent’s judgment of the significance of Saville’s work prevailed: in 2018, “Propped” went up for auction at Sotheby’s in London, and it sold for the equivalent of $12.4 million—at the time, the record price paid at auction for a work by a living female artist.

At the Albertina, Saville acknowledged that the “Fates” paintings were excursions in deconstructing the robust figurative tradition in which she had so definitively inserted herself with “Propped.” She sounded slightly unsure of her success in the endeavor. “I don’t really like postmodernism,” she told me. “I’ve never made work that analyzes painting in itself too much.” She mused, “It’s not that I don’t like these pictures, it’s just that they are a slight experimentation.” Still, in their allusion to the art of venerable precursors, the “Fates” series was as fearless in its ambition as her undergraduate efforts had been. When I mentioned that the trio of paintings brought to mind Francis Bacon’s smeary triptychs of seated figures—these include his celebrated “Three Studies of Lucian Freud”—Saville said, “Yeah, I love Francis Bacon. I definitely feel I’ve got a kind of crew of artists that I go around with, and belong in the conversation with, hopefully.”

Later this month, museumgoers in London will have the opportunity to assess the artist’s œuvre with “Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting,” a major exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. It is, somewhat surprisingly, the first time that a museum in the British capital has dedicated a solo show to Saville. Nicholas Cullinan, the former director of the gallery, who is now the director of the British Museum, told me, “She’s produced, since the early nineties, an extraordinary body of work that keeps developing and growing and maturing, and in some ways has been overlooked, from a museum perspective.” In October, the show will travel to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

The National Portrait Gallery is not an obvious institution to mount a Saville retrospective, given that it was established, in the mid-nineteenth century, to collect pictures of “the most eminent persons in British history,” with a bigger emphasis on the subject of a work than on its creator. Although Saville often paints closeups of heads, she rarely paints portraits, in the sense of making images of named, recognizable people. At the outset of her career, she decided that she didn’t want to be associated with conventional portraiture, which seemed old-fashioned. She focussed on the human head and face and body, rather than on the individual. Many of her paintings have been self-portraits, in a manner of speaking—her own rounded cheeks, full lips, and big eyes have been discernible in her work for decades. But she speaks of lending her face and body to herself as a matter of convenience; her subjectivity is not her subject.

In Vienna, the exhibition included several depictions of heads as giant as those in a Chuck Close painting. But the images were much less clinical. Saville explained, “I work to have as much empathy in those heads as I can. They are particular to this person. The paintings are not usually using a person for other ideas—they are not as dissociated as that.” In the “Fates” canvases, or in various other works in which multiple bodies are layered and limbs are repeated, Saville’s purpose is not to induce estrangement. “I don’t have an intention of saying, ‘Right, I am going to make a piece where somebody has three legs,’ ” she said. “But, if you look at the Titian painting in the Met of Venus and Adonis, and the way he’s composed it, it’s like there’s a triangle of legs. That’s a really amazing rhythm. I’m not doing it to create a monstrous setup, or to disturb a sense of order. It’s really to put more humanity into it.”

Saville lives in Oxford, where she has three studios: one devoted to drawing, another to painting, and a warehouse in which she can undertake very large-scale works. She divides her time between Oxford and a home in London, and she has also acquired an apartment in New York City.

I visited Saville in her painting studio earlier this year. Tucked down a side road, the building was anonymous, without a doorbell or a knocker, its purpose betrayed only by a slight smear of reddish paint on the front door. Saville is intensely private about her spaces, and about works in progress; Stefan Ratibor, the director of the London branch of Gagosian, the gallery that has represented her for nearly three decades, told me that he’d visited her studio on just two occasions. The photographer Sally Mann, who has spent time there, documenting Saville at work, told me, “She reminds me in a certain way of how Cy Twombly would work—he was sort of a magpie, picking up a stain on a newspaper, or whatever inspired him. She’s a lot like that—she goes from oil sticks to oil paints to watercolors.”

Saville led me through a small office area, where a desk was piled with books: collections of Greek myths, a volume about death and resurrection in art, a catalogue from a recent Jean-Michel Basquiat show at Gagosian. On the wall above the desk, a ripped-out page showing Velázquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X had been taped above an image of four Warhol silk screens of Elizabeth Taylor—these were reference materials for past or present works. Just outside the office was a courtyard garden, equipped with a table and chairs, where Saville and I sat in bright spring sunlight to talk.

As Saville’s near-contemporary, I first became aware of her work in the nineties, and her presentation of the female body struck me as a bracing challenge to normative standards of feminine beauty and behavior. Like Saville, I’d been simultaneously reading feminist critical theory and magazines that recommended dieting or liposuction. Before meeting her, I’d looked back at early interviews she’d given, and I’d been struck by the confidence with which she had articulated the critique her work offered. “The history of art has been dominated by men,” she told one male interlocutor. “I paint women as most women see themselves. I try to catch their identity, their skin, their hair, their heat, their leakiness.” Her paintings, she said at the time, were not intended to be didactic. They were intended to provoke discussion: “What is beauty? Beauty is usually the male image of the female body. My women are beautiful in their individuality.”

These days, Saville is less eager—or, perhaps, less obliged—to offer declarative interpretations of her work. In our conversations, she was friendly but a little guarded, and occasionally she appeared braced to be misunderstood. She mentioned more than once that she felt her work had sometimes been subjected to wayward analysis: its anatomical verity had been interpreted as a form of violence, and that had never been her intention. Of her early paintings, she told me, “I remember being shocked at the hyperbolic language that was attached to them, in terms of the fatness—‘blubbernauts,’ or whatever,” she said. “I didn’t have ‘fat is a feminist issue’ in my head. I didn’t want to make narrative paintings, so any narrative had to be in the flesh, or in the body. And a bigger body has a narrative of getting to that size, so that narrative in itself was quite interesting. But I can’t say it was necessarily from a feminist standpoint.”

Saville became most animated while talking about paint itself. Her early command of the medium has matured into a self-assured mastery. In the studio, several canvases were in varying stages of completion. There was a large image of a swan-necked young woman with a snub nose and a fleshy mouth, her lower lip sagging slightly on one side, as if she’d just wiped it with the back of her hand. A pair of portraits leaned side by side against a wall. Both heads featured the brownish-pink and ruddy purple brushstrokes that Saville often uses to depict flesh, but she’d also used oil sticks, made of solidified paint, to vigorously mark the heads with lines as vividly yellow and blue and orange as in a Warhol print. The bright colors were actually underpainting, she explained, and would be layered over with more realistic flesh tones; but some of the underpainting would remain exposed, imbuing the work with an almost hidden energy and light. This method, she said, had been influenced by her research into the Greek myth in which the princess Danaë is impregnated by Zeus, who takes the form of a shower of gold. The myth had inspired many works by Old Masters, including several paintings by Titian. Saville had been exploring ways to visually capture the moment of conception. “How do you find the painterly language to depict that myth from a female perspective?” she said.

Some of Saville’s experiments with bright underpainting were on display at the Albertina. Under the influence of religious imagery from the early Renaissance, she had incorporated cerulean and gold lines into depictions of several female figures. In one such work, the gold underpainting recalled Byzantine iconography, and a blue line piercing the subject’s cheekbone and emerging from her nostril evoked the way that, in some devotional paintings of the Annunciation from the fifteenth century, the Virgin is struck by a heavenly beam of light that enters through her window or doorway. “I use this technique a lot now—of going through heads with yellow or gold and then rebuilding over the top,” she explained. “There’s a sort of force, or tension, that gets embedded within the painting.” Flourishes of this type, she said, “kind of creep in, even from looking at graffiti marks with rhythms—or calligraphy. Shapes wrapping around.”

For palettes, Saville uses a pair of long, glass-topped trolleys on wheels, onto which she squeezes deposits of oil paint. When she is working, she stands between the trolleys, a setup that she adopted after visiting de Kooning’s studio, on Long Island, a few years after the painter’s death, in 1997. “I spent hours there, and that was a really formative experience,” she told me. She added that, when she first saw his work, at MoMA, she experienced a sense of recognition, seeing her own passion for manipulating paint reflected in his: “The twists and turns, the reverses, the scrape-offs.” In the Long Island studio, she could see how de Kooning made recipes for his paint-color mixes, and how he used house-painters’ brushes to achieve certain sweeping effects on the canvas. “I thought, Oh, that’s how you got the paint to behave that way—because you had that bowl, with that mixing.” She added, “Many things about the way he worked absolutely changed the way I worked. I think I was able to shortcut a lot of development.”

Saville never met de Kooning, but she did develop a friendship with his peer Cy Twombly, and she considers the freedom of line developed by Abstract Expressionists in America to be as much of an influence on her work as the more obvious precursors of British twentieth-century portraiture: Freud, Bacon, Frank Auerbach. Twombly also shaped Saville’s approach to living. “I went to a lot of Cy’s shows, and watched the way he was, and the way he lived, and the way he travelled,” she told me. “They showed a very international way of being an artist which was very different from a kitchen-sink, British, gray way of being a painter—like Frank Auerbach taking a sandwich in a bag down to the studio every day. Cy would be taking a boat down the Nile.”

Unlike many artists of her professional stature, Saville does not use assistants other than her partner, the artist Paul McPhail, whom she met at art school in Glasgow, where he also made fleshy, figurative paintings and portraits. “He’s washed a lot of brushes,” Saville told me appreciatively. She paints very slowly, sometimes setting works aside for months or years before returning to them. Ratibor, her London gallerist, said, “She’s incredibly precise about her process, and there’s handsome demand with limited supply.”

Even though Saville’s artistic practice is focussed on the human body, she does not use live sitters, preferring to work from photographs. In this, she has some distinguished antecedents: Bacon used photographs when painting portraits of people familiar to him, because, he told the critic David Sylvester, “I don’t want to practise before them the injury that I do to them in my work.” Freud, however, regarded the making of his portraits as a kind of collaboration, albeit one in which he was the dominant partner, and he required his sitters to attend sessions in his studio for months on end. “The subject must be kept under closest observation,” he once explained. “If this is done, day and night, the subject—he, she, or it—will eventually reveal the all without which selection itself is not possible.”

This dictum has never resonated with Saville; indeed, she told me, photography allows her to see what a studio encounter cannot. She explained, “You can capture things about the way the body moves, or the interaction of different bodies, that you just couldn’t get if you said, ‘Can you hold this pose for two hours?’ ” Earlier in her career, she used a Hasselblad film camera to capture the raw visual material from which to construct a painting. In the past decade or so, she has embraced digital photography. Subjects come to her studio for photography sessions that can last several hours; during that time, she told me, their physicality unfolds. “The way bodies naturally move—you have to learn to go with it, because they literally take up shapes that you couldn’t even imagine,” she said. “I just sit there, and speak to them, or let them speak, and they will put arms and knees in forms that you just couldn’t get close to. If you said, ‘Hold still,’ and you wanted to make a painting directly from life, you would never get that specific level of humanity.”

Saville also feels that the presence of a sitter would get in the way of what she is trying to put down on a canvas, which often dwells closer to abstraction than to realism. On another work under way in her studio, the figure was barely visible: a lurid ear, parted lips, a nostril. The shape of the head was obscured by energetic sweeps of the brush in black and blue, with a splash of yellow bursting from the area where a jawbone had been, and might be again. “This one is more in its abstract incarnation,” Saville said. “It’s got really nice areas and elements, but there are two disparate languages, and they are too far apart. There’s not enough human there yet, so I have to keep going until I bring that out.” Her ambition, she said, was to fuse the languages of realism and abstraction—“to get to the realism of our human nature.” She continued, “I have never been able to give up the figure, really. I feel like I’d be throwing the towel in if I did that. That’s not against abstract painting—I love abstract painting. But I think what makes my painting is the tension between those things. That’s a powerful space to work in, between those two elements. If I can get that right, it feels good, and it’s worth the journey.”

Saville was born in Cambridge, England. The second of four children, she had a peripatetic childhood; her father was a school administrator, and the family later moved from the south of the country to Yorkshire, in the north. Her mother was an elementary-school teacher, a job that gave Saville easy access to arts-and-crafts materials. An important early influence was an uncle, Paul Saville, an artist who also taught at a private school in Oxford. He provided Jenny with her first set of paints, and gave her tasks that cultivated her technical skills and powers of observation, such as making a drawing of a hedge in the family garden every day for a year. He also took her abroad to look at art—to Italy, where she visited Florence, Venice, and Mantua, and to Amsterdam, where she was exposed not just to the art of Rembrandt but to his studio, which was restored as a museum in the early twentieth century. Saville learned how the position of a canvas between a window and a hearth had informed Rembrandt’s depiction of light, with the coldness of the daylight contrasting with the incandescent warmth of the fire. Today, she can identify more complexity in the muddy background of a Rembrandt canvas than most people could articulate about the faces of his subjects. The studio museum showed Saville “the nuts and bolts of an artist’s life,” she told me. “It made me feel like the things I was doing, making paintings in my room, was a way I could live.”

Paul Saville had gone to art school in Glasgow, and, in 1988, Jenny followed in his footsteps, drawn by the institution’s strong commitment to painting. Lucian Freud had recently had a show at the Southbank Centre, in London, and Saville recalled to me that “everybody had a Freud catalogue at their feet when they were painting.” Even so, young British artists in those years were principally concentrated on other forms of art, such as video and performance. Saville said, “You almost had to apologize to be a painter at that time”—painting was seen as belonging to an outmoded, hierarchical, and patriarchal tradition. “If you were doing anything interesting, you were almost always not making a painting, and certainly not a figurative painting,” she said.

While in college, Saville spent a semester abroad at the University of Cincinnati, where, in contrast to her curriculum in Glasgow, she was able to take classes in other disciplines, including in the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies department. Saville became hooked on feminist critical theory, familiarizing herself with the work of Julia Kristeva, Hélène Cixous, and Luce Irigaray, among others. The criticism that she read was much more concerned with analyzing literature than it was with interrogating the visual arts, however, and when she returned to Glasgow she set about finding a visual language to express some of that theory. One of the results was “Propped.” Saville said, “I liked painting a nude body, which was very frowned on in feminist studies—‘Where’s the gaze?,’ all that kind of debate. That conflict is what made that painting work.”

Some Saville nudes from this period seemed to resist the boundaries of the canvas. “Trace,” which Saville made under the early support of Saatchi, is filled to the edges with a bulky, mottled body seen from behind, imprinted with the lingering marks of a too-tight bra and panties. “Plan,” from 1993, plays a different visual game: it turns a woman’s flesh into a vast landscape marked with contour lines, like those on a topographical map. The image was suggested, Saville has explained, by the markings that plastic surgeons make before performing liposuction. “I had friends who were drawing on the edges of their body, of where they wanted the boundary of the body to be—they wanted to diet until they reached that line,” she told me. “I thought that was a fascinating desire—what’s making especially women feel like this?” Saville did not herself have body-image issues or an obsession with weight loss: “Actually, I thought it was a bit of a waste of time—all the books you could read, all the things you could do.”

In 1997, both “Trace” and “Plan” were included in the “Sensation” show, at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, which presented Saatchi’s collection of art by young British artists. The show, displaying many works that contained sexual imagery, was a scandalous success. Compared with the Chapman Brothers’ perverse child mannequins, which had penises for noses, or Tracey Emin’s “Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995”—a tent embroidered and appliquéd with the names of dozens of lovers—Saville’s skillfully modelled figures spoke more quietly, large and naked though they were. Some critics praised Saville’s aesthetic distance from her “Sensation” peers. The critic Brian Sewell, writing in the Evening Standard, excoriated the show’s “assemblage of freaks, frauds and feeble failures,” reserving his sole compliment for Saville, who, he said, “avoids the childish pornographic trap, and sustains her promise as a serious painter of female flesh.”

By the time the “Sensation” show came to the Brooklyn Museum, in 1999, Saville had already been taken on by Larry Gagosian, who became her dealer when she was twenty-six. “There was something new in her work that I hadn’t seen before from any other artist,” Gagosian told me. “For a young painter, it was kind of audacious.” He went on, “You look at the scale of the work, and this kind of small woman—it made it kind of amazing, in a way, that she painted on that scale, with that confidence, and with that power.” For his own collection, Gagosian bought a large painting called “Hyphen,” which was a double portrait. He has sometimes displayed the canvas in one of his homes. “It needs a big room,” he told me.

Saville demurred when asked about her fearlessness in making grand-scale paintings while so young. “It was an era when you’d hear about Anselm Kiefer putting a wing of an airplane on a canvas, so my nine-foot-by-seven-foot canvas was not so big compared to that,” she told me, dryly. “I don’t think I am courageous to make large-scale paintings. I just make them the scale I think they need to be.”

Much in the way that earlier artists, including Rembrandt, attended autopsies to learn more about human anatomy, Saville visited a New York clinic to observe a plastic surgeon transforming patients’ bodies. This led to a 1999 work in which at least three different images of a head and torso are painted on top of one another. It is named for a plastic-surgery technique called the Rubens flap, used in breast reconstruction; the term is a reference to the voluptuous figures in Rubens’s work. Saville said, “The language of plastic surgery was really interesting, because people had a fictional idea of what their normality was, which was not what they were. ‘If only I could get this chin done like this, or my nose like this, I would be more of myself.’ ”

Her interest, she insists, was less political than anthropological; her paintings were intended neither to excoriate nor to endorse the kinds of bodies they represented, nor to validate or condemn the choices made by their inhabitants. In the late nineties, Saville met Del LaGrace Volcano, a queer visual artist who is intersex. Saville made a painting of Volcano, called “Matrix,” that mirrors the composition of Gustave Courbet’s homage to the vagina, “L’Origine du Monde.” But, unlike Courbet’s work, which does not include the model’s head, Saville’s canvas extends beyond a sprawled nude torso and exposed pudendum to include Volcano’s goateed, mustachioed visage. In the early two-thousands, Saville made a portrait of a Colombian trans sex worker named Carla. “It challenged my judgment on every single level to see a penis and breasts in the same body,” Saville told me in Vienna, where the Albertina show includes one of the resulting works, “Transvestite Paint Study.” (“Transvestite,” Saville noted to me, was Carla’s term of choice.)

At the time, trans identity and trans bodies were little acknowledged by mainstream culture. “When I first showed those paintings, people were saying, ‘Did you make that up? That’s actually a real body?’ ” Saville recalled. The works are not voyeuristic, nor are they pious celebrations of a marginalized identity; Saville insists that, as with her paintings of full-bodied women, she didn’t mean these images to be polemical. “I’ve never made these paintings saying, ‘This is a good way to live,’ or ‘This isn’t,’ ” she told me. (Reached by e-mail, Volcano said that “Matrix” participates in “the pathologization of intersex and non-binary bodies by focusing on the ‘discovery’ of mixed sex characteristics by doctors. Regardless of Jenny’s good intentions, ‘Matrix’ reproduces the intersex body as a public spectacle and thereby reinforces the status quo.”) In 2005, in an interview with the historian Simon Schama, Saville acknowledged that she had been “searching for a body that was between genders,” adding, “I wanted to paint a visual passage through gender—a kind of gender landscape.” Her recollection of painting Carla was still fresh, and she used charged, almost erotic language to explain how she had applied intense color in the genital area, then run together several tones on the thigh. “I got them all really oily,” she said. She felt that she had only “one shot” with her brush to “keep the color clean but slide them together and create the thrusting dynamic of this leg lifting up.” Some white paint dripped across the thigh; rather than clean it up, she realized that it contributed a useful tension. “In that thigh, I had more about sex than the whole penis put together,” she told Schama. The story was in the paint.

About a decade after Saville became an internationally recognized artist, almost on a whim she bought a huge apartment in a crumbling eighteenth-century palazzo in Palermo, Sicily. She immersed herself in that city’s multilayered history, with its legacy of Byzantine, Arabic, and Norman art and culture. “Here I can be as close to Rubens as I am to Tracey Emin,” she told the Guardian in 2005. A monograph, published by Rizzoli, documents some of her source material during this period: pages torn from dental textbooks on oral lesions, photographs from medical reference books about elephantiasis, faces bruised or bloodied from violence or surgery, Velázquez’s vermillion-clad Pope. The paintings she was making at this time often had a brutal frankness, approaching the boundary where human flesh is revealed to be animal meat. She even painted animal meat: a work called “Suspension,” which at first sight appears to be of a mass of human flesh, is on closer examination the carcass of a headless pig lying on its side, with a trotter limply extended. The image is part odalisque, part massacre, and as red as a Pope’s vestments. “When you see the inside of the body, the half-inch thickness of flesh, there’s a realization that it’s a tangible substance, so paint mixed a flesh color suddenly becomes a kind of human paste,” Saville said in an interview published in the book. She also approvingly cited a famous quote from de Kooning: “Flesh was the reason why oil painting was invented.”

In the late two-thousands, Saville gained a knowledge of flesh unavailable to de Kooning—or to Rubens or Velázquez or Rembrandt or Bacon or Freud—when she became pregnant. In 2007, she gave birth to a son, Arturo. The next year, her daughter, Iris, was born. Shortly before Iris’s arrival, the director of the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, a Baroque chapel in Palermo’s historic center, suggested that Saville make a work to fit inside an empty frame above the altar, previously the site of a Caravaggio painting of the Nativity that had been stolen in 1969 and never recovered. Saville had a friend photograph Iris’s birth and used the images to guide her work. A preparatory sketch showed a bloodied infant in the moment immediately after delivery, being held aloft by a midwife, umbilical cord still attached. The image embodied the convulsive drama of childbirth that is occluded in a traditionally peaceable Nativity scene—“Giving birth is like being in a Francis Bacon painting,” Saville once said. The infant’s suspended posture hinted at the forthcoming violence of the Crucifixion. The painting was never realized; a replica of the lost work was commissioned instead.

By the time Arturo was a toddler and Iris an infant, the family had settled full time in Oxford. After years of being consumed by her art (“My life is subservient to painting—I can’t find a substitute for it in the world,” she’d told the Guardian), Saville became absorbed in motherhood. “I remember going in the studio and having a few hours, and I almost couldn’t do anything,” she told me. “When your children feel pain, you feel pain. That shocked me. If they cried, you almost feel it inside—you actually are physically linked with them. It’s incredibly animalistic.” But she soon discovered that being a parent didn’t diminish her creativity; rather, it offered a tremendous stimulus. For an artist who had spent decades studying and painting the human body, the opportunity to observe the evolving bodies of her children was fascinating, all the more so because their flesh had been generated by her own. “Just watching them grow was so exciting, watching them jump in the bath, or the way they moved around, or the way their bodies were constantly changing,” she said. “They were these human beings that were very mobile, running around, and that became very visually exciting. And the level of love was so beautiful—I felt all these things were circulating in me.”

Artists who are also mothers have sometimes found inspiration in their children: Berthe Morisot, the Impressionist, made many tender paintings and drawings of her daughter, Julie, reading or sewing or gazing out a window; Sally Mann took photographs of her children for a decade. But, in the Old Master paintings in which Saville had steeped herself, representations of children, especially in religious imagery, often missed something essential about their nature, and about the ways in which maternal care taxes even the most devoted. (Raphael’s “Madonna del Prato,” which hangs in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, a short distance from the Albertina, shows a mother of Christ who is remarkably serene given that she is in charge of two toddlers, one of whom is holding a skinny cross sharp enough to take someone’s eye out.) The only image Saville could think of that captured anything close to her experience of the unpredictable movement of childish bodies was a pen-and-ink drawing by Rembrandt which shows a mother struggling to control the wailing toddler in her arms, his shift risen up and a kicked-off shoe flying through the air.

Saville started drawing her son soon after he was born, in an effort to portray what she has called the “unsentimental truth” of early childhood. “He was this whirlwind of limbs and slipping torso as I carried him, which was so exciting,” she told Mann in a 2018 interview. “A drawing of a singular body just didn’t seem enough to communicate this torrent of human movement.” Saville made works that not only alluded to Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and Child but also referenced imagery from drawings by Leonardo and Michelangelo. Saville, using photographs of herself holding her son, layered images onto one another to depict the ceaselessly evolving experience of mothering.

Initially, Saville wasn’t sure she wanted to exhibit these works. Having put so much effort into being taken as seriously as her male precursors, she was fearful of a perceived diminishment. “I had other artists telling me, ‘Wow, if you show these, you are really saying, “Mother,” ’ ” she said. “I thought, if I don’t do that, what does it say about the legitimacy of being female, or being a mother? That’s part of our whole human story. Or what does it mean about me, if I resist it? Yes, I still take myself seriously as an artist, but I have had this whole other bit of life.”

Some critics were indeed harsh. The psychoanalytic art critic Donald Kuspit, reviewing one show of Saville’s mother-and-child drawings and paintings in Artforum, spent less time evaluating her brushstrokes than judging her maternal competence, writing of the depicted mother-child dyad that “their bond is precarious and uncertain” and suggesting that “the mothers in her paintings have profound ambivalence toward their children.” Saville still bristles at the interpretation. “If there’s a crying child, that had beauty, too, in terms of acceptance of them in all their forms,” she told me. “I said to myself, ‘I can’t see that anywhere in art history—that acceptance of the way a child can be sleepy or crying. Why don’t we see that?’ But I’ve seen that read as I don’t like my kids.”

Included in the Albertina show was a large-scale drawing of a mother and child rendered in charcoal on canvas; the composition was based on multiple images that Saville had made of herself and her son. As we looked at the drawing together, Saville explained, “If I land the foot here and then another foot there and there’s a hand here—all of a sudden it starts to create an anchored kind of balance.” The work was titled “Chapter (for Linda Nochlin).” Nochlin, who died in 2017, was a pioneering feminist art critic. In 1971, she wrote an article provocatively titled “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” She argued that feminists, rather than fetishizing exceptions to the masculine dominance of art history—Artemisia Gentileschi, Angelica Kauffman—should acknowledge the deficit induced by historic exclusion of women from art academies and museums, and focus instead on bringing about structural change. “What is important is that women face up to the reality of their history and of their present situation, without making excuses or puffing mediocrity,” Nochlin wrote. Nochlin had been an early champion of Saville’s work, writing in 2000 in Art in America of her “brilliant and relentless embodiment of our worst anxieties about our own corporeality and gender,” and arguing that “no other artist in recent memory has combined empathy and distance with such visual and emotional impact.” In subsequent years, Saville and Nochlin became friends. “She was a multifaceted character,” Saville told me. “She loved ballet, Manet, as well as feminism.”

In the charcoal drawing at the Albertina, the child was not a baby but a boy of about twelve, with heavy dangling limbs and a drooping head. To my mind—the mind of a mother whose son, like Saville’s, is now a young adult—the image offered a poignant evocation of parenting a boy through the transition from unself-conscious childhood to early adolescence, the body of a onetime babe in arms now easily outspanning that of his mother. The drawing referred not just to imagery of the Madonna and her infant but also to Michelangelo’s Pietà, with its grown male body lying dead across his mother’s lap. Saville’s palimpsests of charcoal offered a concentrated representation of the maternal journey, with the rewards of nurture and the pain of sacrifice present in the same instant. “I try to combine love, tragedy, different emotions in the same picture,” Saville said. “That’s when they become like human maps. Can you have multiple emotions in the same picture, where when you look over here you feel this, and when you look over here you feel another way? And can you span that trajectory of life in the same image?” She went on, “There’s a sense that the whole composition cannot exist in real life. But, when you first look at it, is there a sort of believability, a suspended reality that is more real?”

Saville is close to her children, who are now in their mid- to late teens, and she has continued to draw and paint them with their supportive assent. In 2020-21, she made a large painting of Iris’s head, her full lips parted and one side of her face bathed in a wash of prismatic color. “When I have depicted them, I feel a level of beauty that I haven’t experienced to the same depth with other picture-making I did before I had them,” Saville said. “They gave me a lot of permission for beauty.” If Saville’s early work challenged the viewer to reconsider received ideas of what makes an attractive body, or even an acceptable one—and if her investigation into how flesh works led her to use medical textbooks and sometimes lurid images as the starting place for her pictures—her recent paintings of large heads ravish the onlooker. “I have learned that, when you work with very dramatic imagery and you’re making a painting of that, the paint can’t get beyond the image,” she told me when I visited her studio. “ And so I have learned that working with a more simple portrait means the paint can be more visually exciting, and can be a more joyful thing to do.”

In late May, a few weeks before the opening of the show at the National Portrait Gallery, I met Saville around the corner, at the National Gallery, to look at some of the work that has informed her artistic practice. We began with Leonardo, whose Burlington House Cartoon—a charcoal-on-paper drawing of the Virgin and Child along with St. Anne and the toddler John the Baptist—hangs in its own small room, dimly lit in order to insure the work’s preservation. When Saville was a child, her parents inherited a small reproduction of the image, and it had always fascinated her. “I liked how you couldn’t really tell whose leg belonged to whom, and how it became a kind of collective image,” she said. As our eyes adjusted to the darkness, Saville’s commentary illuminated the artist’s technical accomplishment: the way Leonardo had made a knee appear to come forward from the flat surface of the paper; how the rhythms of certain gestures led the eye around the composition; how, within a monochrome palette, he had achieved emotional effects with differentiated tone. “If you look up close, it’s very warm on the eyelid, because he uses the inner glow of the paper as the warmth of the eye, and then on the cheek he uses this white, which gives the translucence of the flesh,” Saville said, adding, “There’s such an act of love in the making, too. It is so cared for, in the bringing out of that form. The depiction of the knee—there has to be love embodied in the process of doing that.”

We moved on to a spacious gallery devoted to the work of Titian, and stopped before three large canvases based on tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. At the center was “The Death of Actaeon,” in which Actaeon, having disturbed the goddess Diana while she is bathing, is killed by his own hounds. Titian was in his eighties when he began the painting, and it remained unfinished at his death. Saville pointed to places where Titian was harnessing long-developed methods: the light falling on Diana’s forearm, the negative space between the trees in the background. “Look at the way the dog is depicted,” Saville said. “He delineates the underbelly with just one dark stroke. He’s painted that cloth in carmine, and that water, and the transition of different aspects of fauna, or flesh, so much in his life that he’s developed a kind of shorthand way of doing it. You take more liberties. It becomes more playful. You know what works, and what doesn’t.”

In a nearby gallery, Saville stopped before a portrait of Philip IV of Spain, by Velázquez, and remarked at the skill with which the artist had made a curl of light-brown hair lift from the monarch’s brow. “All his flesh is one,” Saville observed. “When you are making a portrait, you have to make sure everything joins together, even though we’ve socially named these parts of the head separately, like eyebrows, for example,” she said. “That’s what makes Velázquez’s paintings so poignant, because he’s able to bring that flesh together.”

We sat down on a bench before the Velázquez portraits. “There are rules when you make a picture, if you want it to have three dimensions,” Saville said. “There’s definitely a rational way of working if you want a chin to go out, for example, or you want a neck to sit behind a chin.” She went on, “There’s a level of rationalism required in order to do that. But you can also have a sort of suggestive poetic nature within it.”

Around us, other museumgoers paused before the paintings; sometimes a visitor took a photograph of a canvas before moving on. Until recently, Saville was an avid user of an iPhone camera, documenting shapes or colors or shadows that she came across, with a mind toward incorporating them into her work. The classical plinths on which the figures in her “Fates” paintings sat were derived from images of blocks that she had seen on a vacation to the Greek island of Delos. Lately, though, she has tried to keep her iPhone in her pocket. “Instead of taking a photo of something, I just stop and look,” she told me at her studio. “Because we are on screens all the time, it’s quite an enriching thing to do to stop and hold that memory. It’s almost like an experience is not complete now unless you take a photograph of it. And I told myself, ‘Maybe there’s something missing in that.’ ”

Saville explained that seeing the pink of a flower against the green of a leaf in her garden will sometimes inform which oils she mixes onto her glass palettes, or which pastel she selects from the box. “The way a lemon sits on a marble table with a shadow—why is that so beautiful? As I have got older, the more beautiful things are what I have become attracted to,” she said. “If you’d asked me when I was twenty-five, ‘Are you interested in flowers?,’ I would have laughed, because it would seem such a cliché. But, in fact, they are so powerfully beautiful.”

Saville doesn’t rule out where these new interests might lead her. In Greece, she painted sunsets to study the transition of light to use for portraiture; she might yet try painting still-lifes. Nevertheless, she always goes back to the birth of her own fascination with flesh. “I’m very committed as a figurative painter that paints portraits and bodies,” she said. “That’s a lot, just that subject. That’s a lifetime’s work.” ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content