Eamonn Forde Meets… – each month, the veteran music business journalist speaks to a senior industry figure about the topics that really matter – and gets the opinions of the people who make the decisions that count.

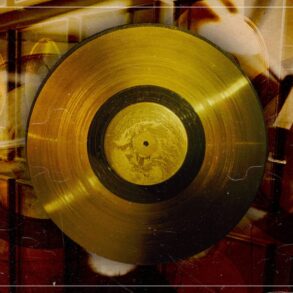

June 2025: Alan Wallis, CEO of Dynamite Songs. The price of rights: blockbuster catalogue sales became a core characteristic of the rights business half a decade ago where some of the biggest songwriters and music stars started cashing out with the kinds of deals that made their lifetime earnings to that point seem like chicken feed. Wallis, when at Ernst & Young a quarter of a century ago, was both spectator and cartographer of such deals in the early days as they started to gather speed.

He talks about the early days of catalogue valuation, the companies and deals that put a rocket under prices alongside the financial conditions that exacerbated it all, how the basket of rights has had to expand to keep pace with the money being sought, why the market hype might now be in retreat as deals become more sensible (or certainly less cavalier), how we got here in the first place and what happens next.

Queen, Pink Floyd, David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, Sting, Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, Kiss and Michael Jackson are merely the headline-grabbing names in the phenomenal catalogue sales boom in recent years.

This is where deals reported to be in the hundreds of millions (and now, with Queen, over a billion) are apparently the norm. The shape and scale of these deals are the new part here, with the jaw-dropping sums being tabled helping to smoke out acts of a certain age who feel this is their ultimate pay day and expediting their desire to sell before the bubble bursts.

Buying huge catalogues, of course, is nothing new, but in the past they were definitely rare and often caused the writers and artists behind the hits tremendous anguish if their songs were sold out from under them.

A useful historical example: This artist anguish is nowhere more apparent than in the selling and reselling of the John Lennon/Paul McCartney songbook. Northern Songs was set up in 1963 by publisher Dick James and Beatles manager Brian Epstein (who were majority owners). It became a public company in 1965, but James sold his stake to ATV Music in 1969 and it caused a domino effect whereby ATV acquired the whole catalogue (but Lennon & McCartney kept their own songwriting shares).

ATV’s 4,000-song catalogue was later bought by Robert Holmes à Court in 1982 and he sold it again in 1985 to Michael Jackson; but a decade later, due to financial problems, Jackson had to sell half to Sony, thereby creating Sony/ATV. By 2006, amid yet more financial problems for Jackson, Sony secured an option to buy the other 50%, triggering this in 2016, seven years after Jackson’s death.

Having watched it change hands several times and having been unable to lead a winning bid, McCartney has voiced his enormous displeasure at this state of affairs numerous times.

The ossified narrative holds that catalogues only became blockbuster events in the 21st century when streaming proved to the record business that it had a viable future and could claw its way out of the wreckage caused by piracy and cratering CD sales. That is true – to a point; but deals were happening in the dark days when label trade bodies were reporting face-clasping declines.

Alan Wallis was running the music transactions practice at Ernst & Young in the late 1990s and early 2000s and says demand for catalogues was always there, even if the wider industry prognosis was becoming bleak. “This was when private equity started coming into the music market,” he says. “It was mostly publishing in those days. Masters came along a bit later on.”

Wallis has valued enormous catalogues, including at EMI before its sale to Terra Firma in 2007, as well as for Paul McCartney (during his divorce from Heather Mills in 2008) and for the Michael Jackson estate (for estate tax purposes). “At Ernst & Young, I did the Three Ds – debt, divorce and death,” he says with gallows humour.

Streaming pushed catalogue prices up

He asserts the interest in music catalogue predates the 2008 financial crash when debt was cheap, interest rates were low and downloads were offering a glimmer of hope for the music business. It accelerated, however, when subscription streaming started to take off. “Everyone was then raising $200 million to go and buy catalogues around 2015.”

Recent years had seen the snowballing of a bidding war culture as major labels and new entrants fought to get the biggest names and catalogues; but even in the bleak days there was assertive bidding.

“There was always one buyer out there and where prices got a little bit hot and then they cooled down again,” he explains. “But there was always a market – until 2008 to 2012 when there was no market. There was always one buyer out there, who was probably doing most of the deals. Imagem was probably the first.”

“All the majors did those big deals […] it’s about ego and market share.”

Alan Wallis

The relaunch of BMG (after Sony Music bought out Bertelsmann’s 50% stake in Sony BMG) in 2008 and a subsequent major investment in it by KKR in 2009 was, Wallis argues, another key moment here as it looked to build market share swiftly by buying catalogues. Then the arrival of Hipgnosis in 2018 saw the market rapidly move up several gears. Although it was to run into all manner of problems later, Hipgnosis dramatically changed the temperature and contours of deals here.

“Hipgnosis certainly had a reputation where, if they wanted it, they’d go and do the deal – but there were lots of deals they never did,” says Wallis. “We bought catalogues at reasonable prices, where they’d been promised higher prices by Hipgnosis, but then they lost interest.”

This raised the stakes for the majors who could not afford to let mega-catalogues slip out of their control. “All the majors did those big deals,” notes Wallis. “It’s [about] market share. Sorry, when I say ‘market share’, it’s ego and market share.”

The changing rights market

As deals get bigger, and as competition increases, the basket of rights being put up for sale is changing. From publishing rights to master writers to image, name and likeness rights, it has become a rights arms race.

“In the old days, you never sold your writer’s share,” says Wallis of the old system. “You sold your publishing but you kept your writer’s share as that was your pension.”

He says, due to their size, the majors are built only to do “$25 million deals”, but this is leaving a very healthy space were more sensible and modest deals – in the hundreds of thousands of dollars – can be done.

Wallis feels the frantic land grab of a decade ago is increasingly anachronistic. It is becoming less about the headlines and more about the bottom lines.

The focus is [now] on assets, both publishing and masters, you can control.”

Alan Wallis

“It’s probably a bit softer at the moment,” says Wallis of the current state of the acquisitions market. “More sensible deals and a drive to quality. So it’s not people buying all this ancillary income and neighbouring rights. The focus is on assets, both publishing and masters, you can control.”

There are very few mega-catalogues left to buy – and therefore to skew the market by dominating media coverage of this sector of the market – and they may never even be for sale. Things are now recalibrating towards something approaching normal. It also means the end of, let’s say, optimistic self-valuations where songwriters and artists (or publishers and labels) are asking for hyped-up multiples.

“Someone saying they’ve got this little country catalogue, with the writer’s share, but they say they are worth the same as Bruce Springsteen so they want 25x?” says Wallis. “That’s gone.”

The market as a whole should benefit long term from the death of the era where reality was slipping its moorings and top-tier prices were being asked for mid-tier catalogues.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content