GREENVILLE — What is art worth and who gets to decide?

In a recent discussion, Christopher Rico was told his work — which currently sells for thousands of dollars — was too expensive.

“That is an arbitrary statement, that implies knowledge of value,” Rico said. “What you really mean is, either it’s not within your budget, or it’s not within the project’s budget.”

Rico is an abstract painter whose work appears in galleries across the country and on the walls of his studio space in Greenville’s North Main neighborhood.

His career spans nearly 25 years, but his work has only turned a profit in the last 10.

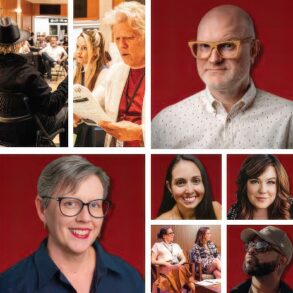

Christopher Rico is an abstract painter based in Greenville, S.C. Emily Garcia/Staff

Despite the seemingly steep price tag attached to his pieces, Rico pays more than $1,000 per month to cover basic costs. These include rent for his studio, the cost of his storage space, web domain and some materials.

The wood panels he paints on are custom made and cost more than $100 each. His paintbrush is the size of a baseball bat and made of horsehair. It cost more than $500.

All of these costs are factored into the price he charges, as well as the length of his career.

It’s an unspoken rule in the art world that the longer and more established an artist’s sales history, the more they can charge. Prices should increase gradually — so as not to out-price the market — and never decrease.

“Once you go up in price, it is really detrimental to your career to go back,” Rico said, because it’s unfair to customers who paid a higher price.

The price of art is also determined by the galleries that sell it. Galleries usually split profits with artists 50-50. In bigger cities, there’s an incentive to only hang high-priced items on the walls to offset the higher cost of doing business.

Even if people in New York were willing to pay $3,000 for one of Kent Ambler’s woodcut prints, it’d ruin his market everywhere else.

Ambler charges a few hundred dollars for one of his prints. It’s relatively inexpensive but Ambler still makes a profit. With a few carved wooden blocks covered in paint, he can make 20 or 30 of the same print.

He also doesn’t pay studio fees because he works in a space he built in his backyard. He’s out there about 12 hours a day, every day of the week.

For him, there’s a tension between making the art he wants to make and making the art that will sell easily. He wants to start painting more, but he’s probably best known for his woodcut prints.

Some galleries are reluctant to carry both his woodcuts and his paintings, so he’s considering listing them himself on ArtCloud — a website service for artists.

Ambler’s work currently is for sale in several galleries. He also gets a good amount of his sales at festivals.

Before the pandemic he was traveling to 10 or 12 festivals a year, setting up a tent and introducing people in new cities to his work. He’s been trying to cut back to four festivals per year, but last year he attended six.

As an artist, meeting people is one of the best ways to market pieces outside of galleries and social media.

Jessica Leitko Fields sort of dabbles in everything. Her color-saturated work hangs in two galleries, and she sells it herself online. This year she hosted her first booth at Artisphere.

Jessica Leitko Fields sort of dabbles in everything. Her color saturated work hangs in two galleries, and she sells it herself online. This year she hosted her first booth at Artisphere. Emily Garcia/Staff

“Streamlining would make sense but that’s just not who I am,” Fields said. “I’m gonna be scattered all over the place.”

As Fields has grown in her career, she’s raised her prices. She cares about getting fair compensation, but it’s difficult to charge more because she wants her work to be affordable.

“I want people to have art, but I can’t afford art,” Leitko said. “I’m so lucky to trade (with other artists), so that’s where I get most of my stuff.”

Jessica Leitko Fields is an artist in Greenville. Emily Garcia/Staff

Her paintings usually sell for a few hundred dollars. She also makes small pieces and prices them at less than $100.

When selling paintings on her own, Fields handles everything from taxes to shipping.

She finds the business part of being an artist, “brain numbing, and confusing.”

“I’m always questioning myself and my choices,” she said. “But the painting part is … like getting to meditate daily.”

On the whole, she loves what she does and wouldn’t change careers.

“I’m forever lucky, like the luckiest person alive,” Fields said.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content