The Year in Reading

The New Yorker’s editors and critics considered hundreds of new releases this year in order to select the Best Books of 2023. The magazine’s writers also came across many other new favorites—classics they resolved to finally tackle, memoirs and biographies they drew on in their writing, an art book that is a beautiful object in its own right, a centuries-old poetry collection, a guide to writing thrillers, and other overlooked gems. Their recommendations are below.

Spurred by the delightful documentary “Turn Every Page,” I decided that 2023 would be the year that I finally began to make my way through Robert Caro’s biography of Lyndon B. Johnson, the sort of book one wants to have read—and thus must, at some point, read. But what a pleasure the reading of it turned out to be! I had been warned about the lengthy description of the grass of the Texas Hill Country that opens “The Path to Power,” the biography’s first volume, as if Caro’s rigorous attention to the history of the landscape that made Johnson’s boyhood might put me off before I got to the good stuff. Actually, it reeled me right in. “To these men the grass was proof that their dreams would come true. In country where grass grew like that, cotton would surely grow tall, and cattle fat—and men rich. In country where grass grew like that, they thought, anything would grow,” Caro writes of Johnson’s forefathers, the white settlers who thought that the unspoiled Hill Country held the key to their fortunes. (Spoiler alert: they were wrong.) What I love here is Caro’s musical grasp of rhythm and repetition, and his use of short, blunt words; this is mythic writing used for the purpose of puncturing myth. His superb grasp of character, too, benefits from a certain mythic understanding of human nature. Caro is a believer in nature and nurture both; he shows us how Johnson was shaped by the place and the people he came from, and how he determined to shape himself in defiance of them, but he doesn’t discount the innate ambition that Johnson seems to have been born with. Count me among the legions rooting for Caro to finish his fifth and final volume.—Alexandra Schwartz

For the past several months, I have been reading to write an essay on marriage. My reading list was determined by friends whom I e-mailed to ask for their favorite “marriage stories”: “a story,” I wrote, “which tells a truth about marriage but—and this is important—does not foreground courtship, adultery, divorce, or death.” Almost everyone who responded observed that this was a surprisingly challenging question. Their answers, when they came, ranged from novels to stories to poems, but it is Phyllis Rose’s “Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages,” first published in 1983, and reissued in 2020, which remains the most companionate book on my list. Marriage, Rose writes, is “a struggle of imaginative dominance,” the smallest unit in which the freedom of fiction—the freedom to dream, to tell stories—is cramped by the unequal distribution of power. The uneasy union of art and politics yields two plots, the plot of the conquering male and the plot of the suffering female, which Rose threads through her investigation of the Dickenses, the Carlyles, the Ruskins, the Mills, and the happiest couple of them all, the unmarried George Eliot and George Henry Lewes. Rose speaks of her couples as one might speak of friends; she is, by turns, inquisitive, tender, skeptical, and animated by the high spirit of gossip, which she wants to redeem as “the beginning of moral inquiry.” Thinking of the friends whom I have gossiped with recently, I wonder if Rose’s two plots have been succeeded by a third: the marriage of the conquering female and the thwarted male, as seen in “Fleishman Is in Trouble,” “Fair Play,” and “Anatomy of a Fall”—all featuring couples who are aware of feminism’s lessons but incapable of inhabiting them peaceably or desirously.—Merve Emre

Symbols fade, but irritation is timeless. And so, while we can only guess at what “ground geckos” or a “brocade zither” meant to the ninth-century poet Li Shangyin—best known for cryptic verses about love—his inspired kvetching about everyday life in Tang-dynasty China feels as current as a text from your wittiest friend. “Derangements of My Contemporaries,” translated with sardonic simplicity by Chloe Garcia Roberts, is his masterpiece of misanthropy, a catalogue of follies, peeves, and misfortunes that doubles as a portrait of a society in decline. The poems take the form of deadpan lists. “Definitely Not Coming” begins with “A courtesan being called at by poor aspiring scholars,” while “Contradictions” invites us to imagine “A gaunt petty official” and “A butcher reciting Buddhist scripture.” The form is such a perfect container for annoyance that it burrows into the unconscious; once, driven to my desk by insomnia, I wrote an inadvertent homage called “Obstructions to Sleep.”

Li, a scholar-official whose ambitions were thwarted, gives vent to frustrations by turns relatable and comically élitist, heaping ridicule on bullies, hypocrites, and poseurs but also “vulgar” common folk who commit such faux pas as “casting divination blocks” or playing the flute while riding an ox. (“Cannot Abide” begins with “A fat man in summer months / Entering the residence of a hateful wife.”) Often, though, snobbish pique yields to a more rueful and ruminative mode, as Li reflects on the waste and futility around him. In the title poem, he sketches a haunting tableau of disordered responses to adversity: “Drunkenly calling on ghosts and spirits . . . Enemies reminiscing / Grown men flying kites.” Behind the scorner and the mourner is a poet who delights in the absurd, observing that “nuns, like weasels, enter the profound,” or that “a capital bureaucrat, like a winter melon, grows in gloom.” His world is long gone, but its petty derangements—and the secret joy of noticing them—are still with us.—Julian Lucas

In 1984, a filmmaker and activist named Ben Caldwell established a community art and media center, in Leimert Park, in South Central Los Angeles, that would become known as KAOS Network. His dream was to create a place for young African Americans to build sustainable, self-reliant systems for producing and distributing their art. In the nineteen-seventies, Caldwell had been part of a community of young Black filmmakers in Los Angeles—a movement, which included Charles Burnett and Julie Dash, later dubbed the L.A. Rebellion—and he hoped to empower the next generation of kids to fashion their own alternatives to traditional media. He opened KAOS Network to all: a group of young rappers who would later become known as Project Blowed; videographers and aspiring journalists; Afrofuturist thinkers and writers; drag-ball performers; and also Yoruba Christian congregations, theatre companies, dancers, and artists. Today, collaborators working out of KAOS Network are making games, augmented reality, even autonomous vehicles. “KAOS Theory: The Afrokosmic Ark of Ben Caldwell,” by Caldwell and Robeson Taj Frazier, a professor at U.S.C., is a spellbinding book documenting the filmmaker’s life and work. Caldwell’s restlessness of spirit is mimicked in the book’s elaborate, frenetic design. It is one of the most beautiful objects I held in my hands this year, a coffee-table book as much as a rigorous monograph, full of archival images, photographs, flyers, and documents telling the story of Caldwell’s life, from his New Mexico childhood, to his military service in Southeast Asia (where he first became seriously interested in photography), to his arrival in Los Angeles, in the seventies, all of it culminating in KAOS Network, and the worlds Caldwell has helped manifest.—Hua Hsu

Claire Keegan’s “Small Things Like These” is a slender novel that can be read in one sitting. Since reading it this summer, I haven’t stopped thinking about the book, both because of Keegan’s luminous prose and because of the crisis of conscience that unspools within its pages. Set in a working-class town in Ireland in 1985, the novel’s protagonist is Bill Furlong, a coal and timber merchant whose customers include a local convent that takes in “girls of low character” and puts them to work in a laundry. Rumors have circulated that the girls in the laundry are cruelly exploited. There is even talk that the convent turns a profit by arranging for wealthy foreigners to adopt the girls’ “illegitimates” (babies born out of wedlock). Furlong is not inclined to believe such talk—he is determined “to keep his head down and stay on the right side of people,” not least to provide for his wife and five daughters, who might wish to attend St. Margaret’s, a school affiliated with the convent, at some point. But a few days before Christmas, he visits the convent to deliver a load of logs and finds a girl locked inside a coal shed. Her fourteen-week-old baby has been taken away from her, she tells him.

As Keegan notes in an afterword, such scenarios were hardly uncommon in Ireland’s Magdalene laundries, where tens of thousands of “fallen women” were forced to labor under squalid conditions and babies died routinely. (The historian Catherine Corless revealed that, in one Mother and Baby Home in County Galway, seven hundred and ninety-six children died.) Furlong’s own mother might well have shared the fate of these women, had a Protestant widow with a large house not agreed to take her in after she gave birth to him, at the age of sixteen. After he discovers the girl in the shed, the drama in Keegan’s book unfolds mainly in Furlong’s mind, as he wrestles with whether to do nothing—the prudent course—or to follow his moral compass and rescue her. I can’t recall a novel that captures this predicament more forcefully, attuned both to the price of silence about a shameful public secret and to the chance encounters that can spark the flicker of conscience and lead a cautious, seemingly risk-averse person to refuse to be complicit in it.—Eyal Press

Earlier this year, I posted a picture on Instagram that I took while rewatching my favorite Bravo reality show, “Vanderpump Rules.” The image was taken from a scene in Season 2, in which Kristen Doute, a restaurant server who had split with her bartender boyfriend, Tom Sandoval, goes over to an apartment they used to share and where he still lives, supposedly to pick up some mail, though her low-cut dress and carefully curled hair tell a different story. Tom, who has moved on with another bartender, reacts frostily, and Kristen is gutted by his uninterest, which the viewers already anticipated. “Kristen coming to pick up her mail all dolled up from an apathetic Sandoval has deep annie ernaux self-abasement vibes,” I wrote in the caption. Yes, like many of my peers, I had been reading Ernaux’s autofiction, and I couldn’t get enough, especially of books like “Getting Lost” and “A Girl’s Story,” which deal with exactly the kind of humiliating lows a woman might fall to when experiencing Kristen-style heartache. And so, when the writer Lucinda Rosenfeld commented on the post, and suggested that I try another novel in a similar vein (“Speaking of deep self-abasement vibes,” she wrote, “have you read Willful Disregard by Lena Andersson?”), I jumped.

Andersson, who is Swedish (“Willful Disregard” was translated by Sarah Death), has created a much more cerebral heroine than Ernaux’s, and yet, as the book shows, the pain caused by love’s lament is no less pointed for the rational language it is couched in. Ester Nilsson is a critic who is asked to give a lecture on the work of an older, well-known artist, Hugo Rask, and almost immediately falls in love with him. Hugo and Ester sleep together, but while she enters, heart-first, into an all-encompassing passion, he remains emotionally detached, a fact that Ester is unable to accept, certain that in the end, he will be hers. What follows is a stunning study in self-delusion and obsession, all the more sympathetic because it is so familiar. “It could not be the case, she argued, that feelings for another person evaporated from one day to the next, and he must have had feelings, otherwise he would not have invested all that time in spending those hours with her,” Andersson writes. “The clear logic of this made it very easy to mobilize hope.”—Naomi Fry

Balzac walks into an art opening. He stands before a painting of a cottage on a winter day. He turns to a painter and asks, “How many people live in that cottage?” The painter doesn’t know. Balzac asks, “What’s the typical dowry?” The painter doesn’t know. Balzac asks, “What’s the going rate for grain? How was the harvest?” The painter doesn’t know. Cue Balzacian righteous huff: “If you cannot answer such questions,” he tells the painter, “What right do you have to paint even that wisp of smoke leaving the chimney?”

My memory is hazy, and the story possibly apocryphal. But it cuts to the heart of the questions animating so many of my favorite recent books, particularly Christina Sharpe’s “Ordinary Notes,” and Selby Wynn Schwartz’s “After Sappho.” What do I know, what can I know, and who sets the terms of my knowledge? I found a companion in an older work, Arlette Farge’s 1981 “The Allure of the Archives,” translated from the French by Thomas Scott-Railton. Farge is a historian of the nineteenth century, and her book, born out of her research in the Archives of the Bastille, reconstructing the lives of poor women in pre-Revolutionary France, is about what it means to work with such records in practical and philosophical terms: how to handle the papers and keep them from handling you, how to think with an ocean of information that is always too much and never enough, and how to pose the questions the archive can answer and those it can’t. Farge’s challenges are nagging and sound, and her mood—her ardor, impatience, mischief—will run through your thinking, leaving its traces everywhere, its own wisp of smoke.—Parul Sehgal

I’ve long harbored a secret desire to write a thriller. Sadly, the will-I-or-won’t-I of writing it is as far as I’ve got in terms of charting a suspenseful narrative. I decided to get serious this year, so I picked up a copy of “Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction” (1966, revised 1981), by Patricia Highsmith. Who better to teach me how to do it? I thought. The first line reads, “This is not a how-to-do-it handbook.” Indeed, Highsmith has not assembled a writing manual precisely. Rather, the book is a guide to living for writers who want to specialize in untimely demises. There are tips on socializing. To remain attuned to your own unconscious, she advises, spend time with people who are not too “stimulating,” and rather “dull-witted, lazy, mediocre in every way.” Other writers are like witnesses, and to be avoided: “Their invisible antennae are out for the same vibrations in the air—or to use a greedier metaphor, they swim along at the same depth, teeth bared for the same kind of drifting plankton.”

Highsmith cycles through various scientific metaphors to make the point that writers are receptors. To possess “awareness of life, is an artist’s ideal, and takes precedence over all his activities and attitudes,” she writes. This is especially true when writing suspense. Your senses must be as sharp as a dagger. (Highsmith reveals that she opens all her letters with one, a gift from the Crime Writers’ Association, in England.) Any “germ” of a story could become a great suspense novel; without warning, it could whack you in the head like the oar Tom Ripley used to kill Dickie Greenleaf. And details in this line of work can mean the difference between a successful frame job or the electric chair. A husband who wants to kill his wife and frame her lover by placing a cocktail glass with his fingerprints on a terrace will not consider that it might rain, because he is a novice to murder. The writer can overlook nothing. In preparation for death, you must look widely for life, Highsmith cautions—good advice, for writers and non-writers alike.—Jennifer Wilson

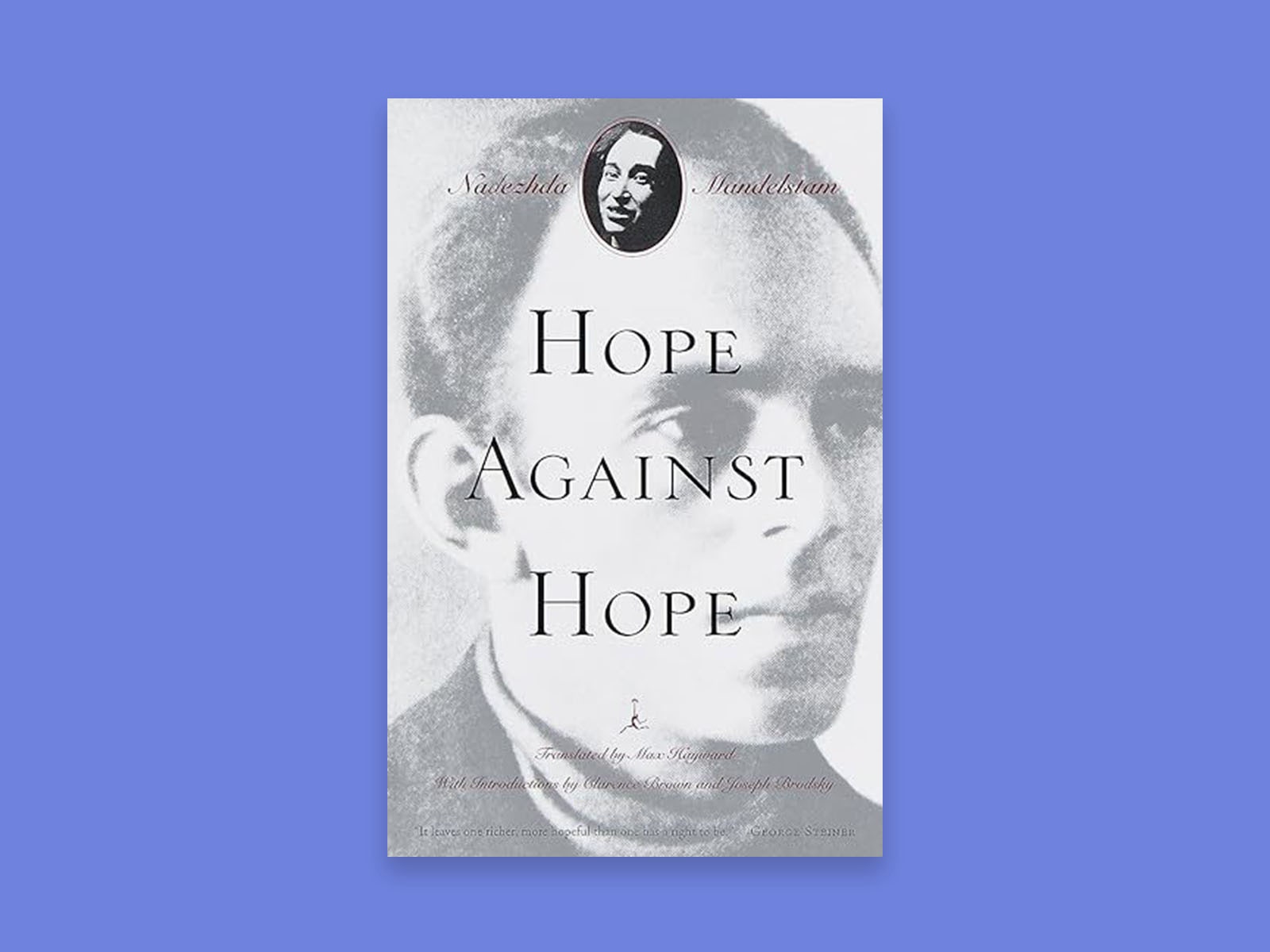

“Hope Against Hope,” written by Nadezhda Mandelstam, the wife of the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, three decades after his death, narrates her husband’s life after he was arrested and exiled during the Stalinist purges of the nineteen-thirties. Initially, the book read to me as almost diary-like, so meticulous and vivid were the descriptions of the couple’s daily life under persecution and surveillance. But it is exactly through this unsparing accretion of details that the memoir achieves its emotional power. There is something unnerving about the forthrightness with which it recounts the pervasive paranoia, delusion, and resignation of a totalitarian police state. “Fate is not a mysterious external force, but the sum of a man’s natural makeup and the basic trend of the times he lives in,” Osip Mandelstam once wrote. Of course, the declaration is true not only of individual existence in a Soviet dictatorship a century earlier but of the relationship between the individual and state through any time in history. Still, it is astonishing to me that Mandelstam and his wife were able to preserve their humanity in an era that so terrifyingly dehumanized an entire populace. More astonishing still is that Nadezhda Mandelstam, whose first name means “hope,” possessed the stamina and resilience to transform into narrative a remarkable life lived out in a society that annihilates both the body and the soul.—Jiayang Fan ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content