It started in early 2018 with a special New York Times series of articles, “Overlooked,” obituaries about notable people whose deaths had gone unreported in the newspaper, which first began publishing obits in 1851.

Leverett printmaker and collage artist Julie Lapping Rivera was intrigued by the series, especially since all of them, at first, were portraits of remarkable women.

“It was fascinating,” Rivera said recently. “I had never heard of so many of these women, even though they’d had these incredibly accomplished or dramatic lives.”

Later that year, Rivera found herself “really agitated” as she followed the hearings for Supreme Court Justice nominee Brett Kavanaugh, at which Christine Blasey Ford testified that Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her years earlier, when both were teenagers in Washington, D.C. (Kavanaugh vehemently denied the charges.)

“I felt like I needed to do something,” said Rivera. “I needed to counter all the negativity and do something positive.”

The result is Rivera’s new exhibit, “Look Again: Portraits of Daring Women,” at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts at the Springfield Museums, a collection of finely wrought, hand-carved woodcut prints of notable women from the past.

Taking some of her cues from the Times’ “Overlooked” series of obits, and adding images of other pioneering women whose stories she’s studied, Rivera has created a striking series of portraits — there are 17 in the exhibit — that can engage viewers as art and history.

Some of her subjects are quite well known, such as Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who received an extensive Times obit when she died in Sept. 2020; and poet Sylvia Plath, who became famous after her death in 1963 but at that moment was not recognized by the Times.

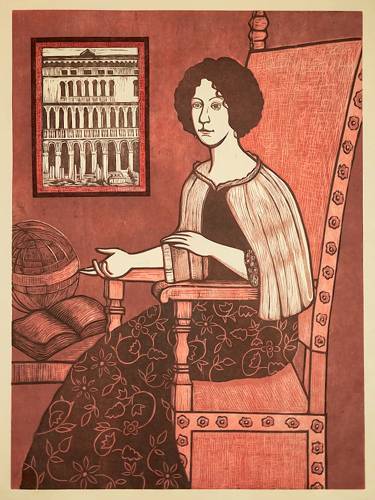

Other portraits highlight lesser-known figures: Bessie Coleman, the first African American and Native American pilot; Caroline Dormon, a U.S. naturalist, writer and environmental educator; and Elena Cornaro Piscopia, one of the first women to receive an academic degree from a university and the first to receive a doctor of philosophy degree — in the 1670s in Venice.

“[Piscopia] was a prodigy — she was brilliant,” said Rivera. “She was celebrated at a time when the idea of women as intellectuals and scholars was unheard of.”

Rivera says her woodcut project is also a response to what she feels is a growing climate of discrimination toward women and marginalized communities in general.

In that sense, her portraits dovetailed with the general thrust of the Times’ “Overlooked” project, which was created to take a fresh look at who and what is valued in society.

“Obituary writing is more about life than death: the last word, a testament to a human contribution,” Amisha Padnani and Jessica Bennett, the New York Times editors of “Overlooked,” wrote in introducing the series in March 2018.

“Yet who gets remembered — and how — inherently involves judgment,” they noted. “To look back at the obituary archives can, therefore, be a stark lesson in how society valued various achievements and achievers.”

From an artistic standpoint, Rivera used some basic reference materials, such as photos, for her portraits but has greatly expanded on those points in her work, using collage, stenciling, and colors to enhance some of her prints.

Though she studied printmaking as an undergraduate, her art for years was focused more on painting and drawing. But she “fell in love” with printmaking about 20 years ago after taking a woodcut class at Zea Mays Printmaking in Florence, and that work is now the center of her art.

“It’s a very slow and unforgiving medium,” she says of woodblock carving. “But that also makes it a very contemplative exercise, almost meditative … I felt it was a really good means for connecting with these women, to get a sense of their lives.”

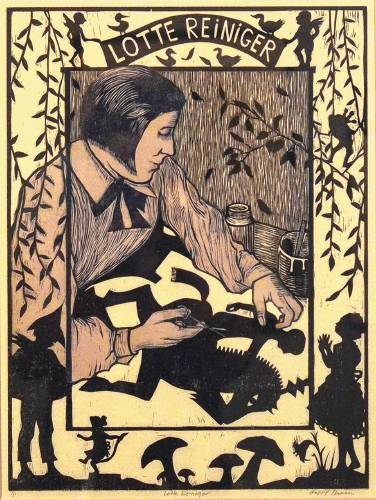

Rivera has used small details in some cases to capture her subjects. Her portrait of Lotte Reiniger, a German-born film director who also pioneered the field of silhouette animation, is framed by the kinds of images the artist might have created: silhouettes of small human figures, toadstools, animals and flora.

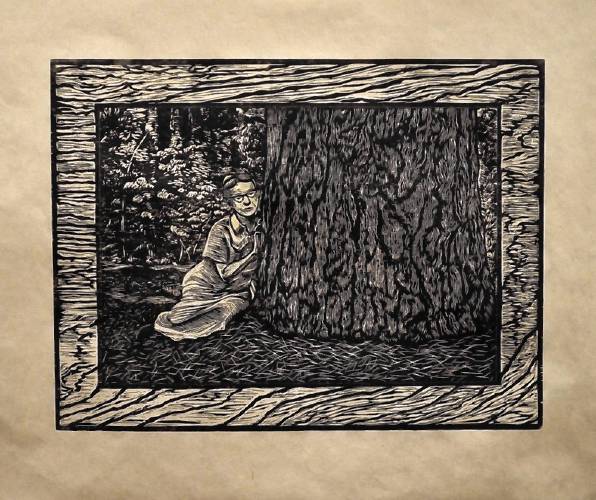

For her profile of Dormon, the 20th-century naturalist, Rivera has created a deeply textured work, with multiple lines and marks that depict Dormon sitting next to the trunk of a huge tree, with a forest behind her and pine needles at her feet. That image is framed within an outlying background of veined wood, like a cross-section of a tree.

“I was worried it might look too busy, but in the end I think it worked,” said Rivera, who teaches printmaking at Smith College and at Zea Mays.

Her portrait of Bessie Coleman is a multi-colored work that shows the pilot standing next to an early biplane. Born in 1892 to a family of sharecroppers in the Jim Crow South, Coleman had to get flight training in France because African Americans, Native Americans, and women had no such opportunities in the U.S. at the time, Rivera said.

“She overcame a lot and then became very successful” as a stunt pilot in the U.S. in the 1920s, Rivera says, while also using her visibility to fight racism. Coleman tragically died in 1926 at age 34 when she fell from a two-seat plane in which she was riding as a passenger.

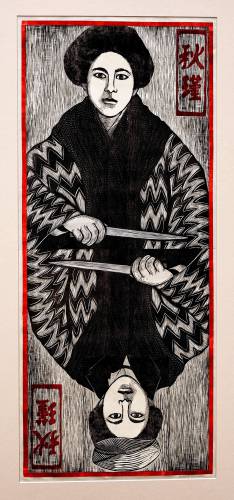

Perhaps Rivera’s most striking portrait is of Qiu Jin, a Chinese woman born in the mid-1870s who became a poet, revolutionary, and outspoken feminist in a very patriarchal society. Known today as “China’s Joan of Arc,” she was beheaded in 1907 by Chinese authorities.

Rivera has posed her like a playing card, with a modified mirror image of her upside down, both figures clutching a large knife.

“That one was so hard,” she said with a laugh. “I felt I must have redone her face 1,000 times.”

There’s more in “Look Again”: The portraits are all accompanied by poems, written by area poets and some further afield who Rivera has gotten to know, that offer further perspectives on the women. Sharon Tracey, for one, celebrates Bessie Coleman in her work “Queen Bess”:

“Built for flight, for soaring, she who / always checked her wings, the weather— // aviatrix, wing-walker, barnstormer, first black woman pilot in the U.S.”

The poems can be accessed via a QR code at the exhibit and are also posted on Rivera’s website, lappingriver.com.

Rivera has created several other woodcut portraits that are not part of the D’Amour Museum show, which is located in the museum’s Albert Gallery. “This is an ongoing project for me,” she said. “I plan to keep adding to it.”

An artist’s reception for the exhibit takes place at the museum on May 31 from 5 to 7 p.m.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

More Arts for you

By using this site, you agree with our use of cookies to personalize your experience, measure ads and monitor how our site works to improve it for our users

Copyright © 2016 to 2024 by H.S. Gere & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content