Today, the pair are rarely remembered. Hotchkis still retains something of a reputation in her native Scotland thanks to her involvement with the Kirkcudbright Artists’ Town community of the 1920s, whereas Mullikin is now almost totally overlooked.

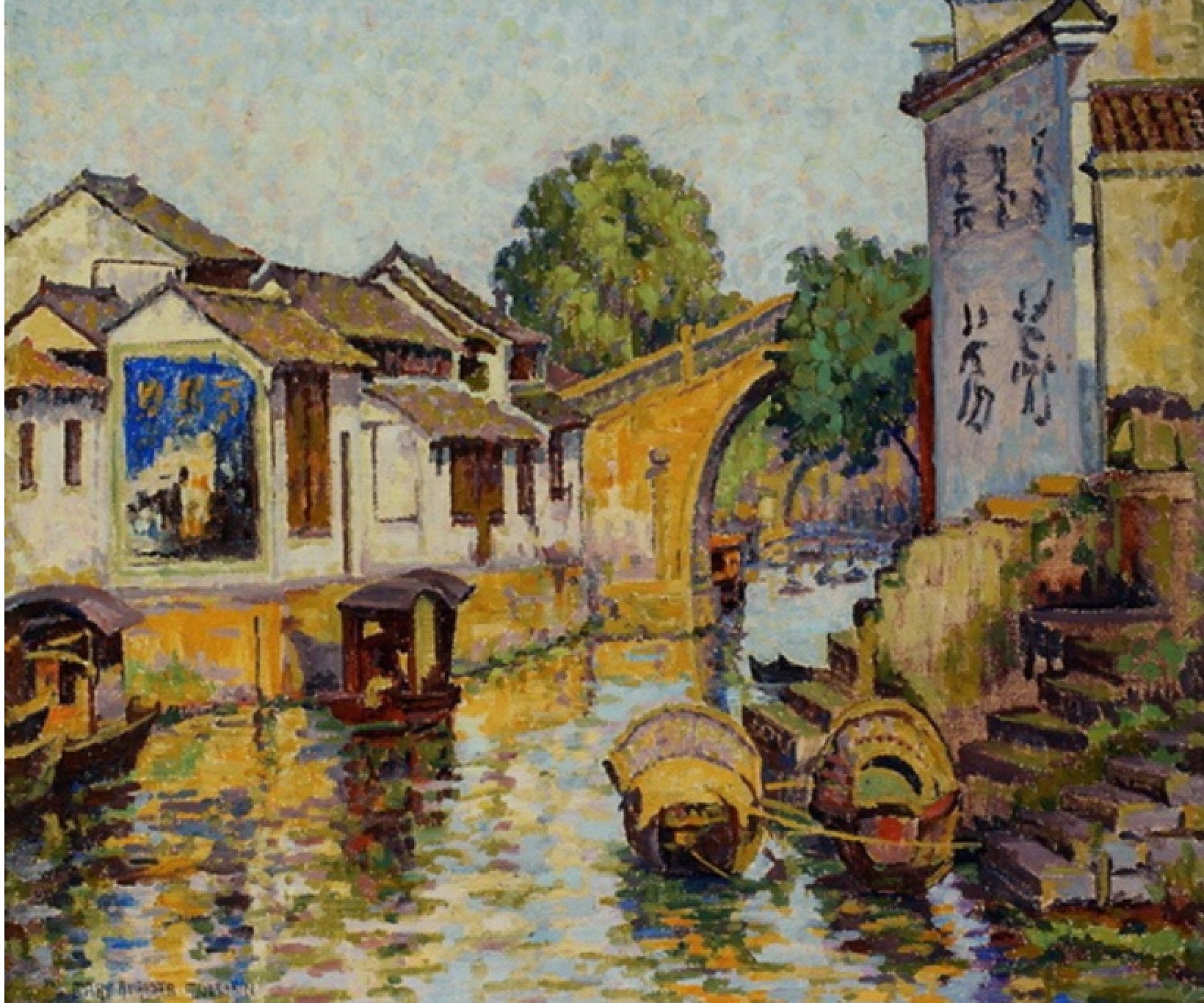

Yet whenever their often uncredited work appears on Instagram or Flickr, it is shared, admired and reposted by a younger generation unaware of who either Anna Hotchkis or Mary Mullikin were.

Those posting the paintings might be surprised by the incredible lives lived by what the art establishment critics of the time dubbed the two “lady artists”.

Between the two world wars their work was exhibited in galleries across China, Europe and North America.

It would seem that, at a distance from the often prejudiced and incestuous European and American art circles, these women not only found time to paint but managed to find a market for their work, first among their fellow expats and then with a wider public fascinated by images of China.

Anna Hotchkis was born in 1885 in Crookston, a southern suburb of Glasgow. The Hotchkis family was large – Anna had three sisters and six brothers (although only one of her brothers survived to adulthood).

She studied at the Glasgow School of Art and then, a year later, when the Hotchkis family moved to Edinburgh, she enrolled at the city’s College of Art, studying under Robert Burns, a proponent of the Arts and Crafts Movement that would so influence Hotchkis.

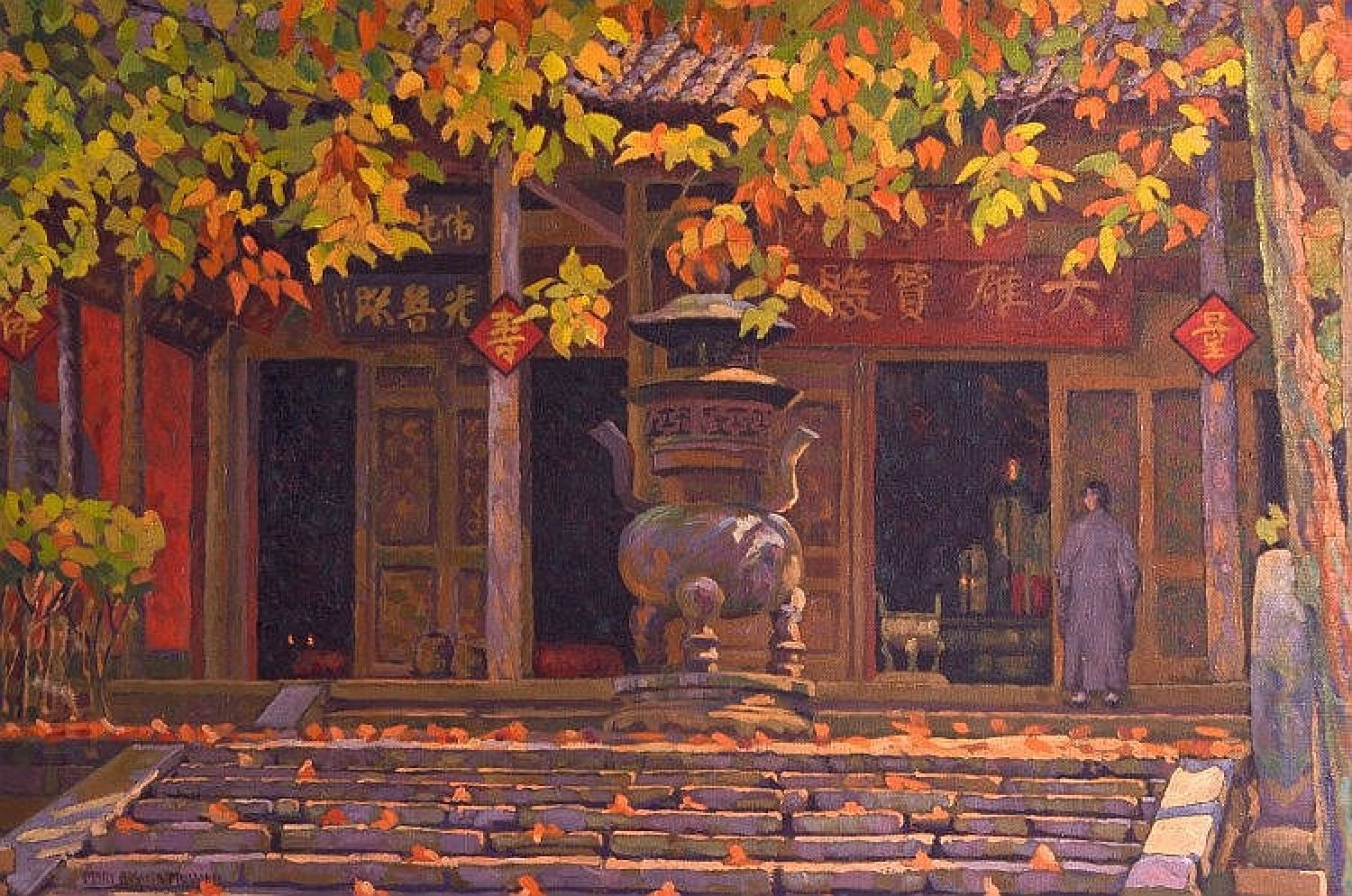

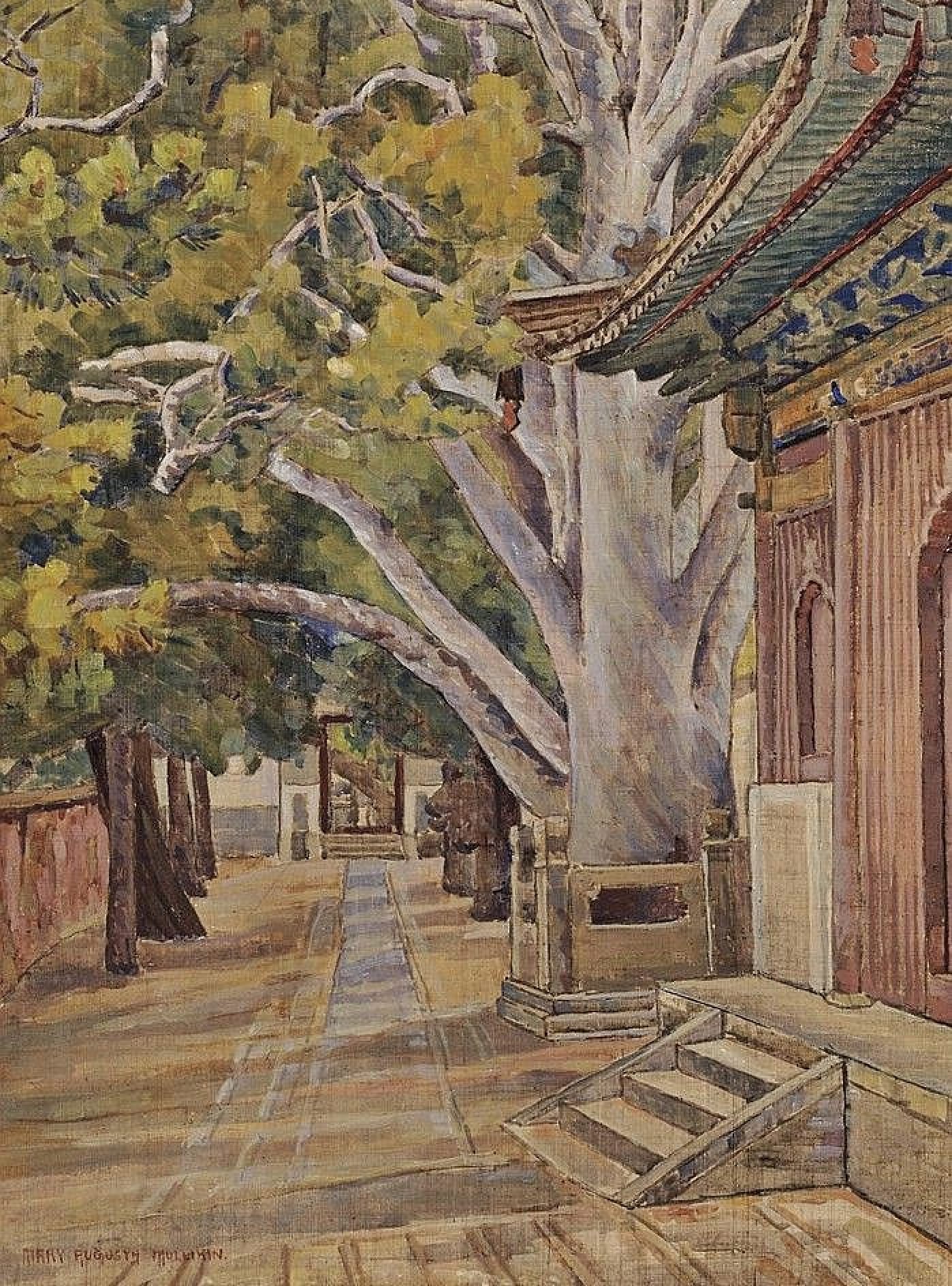

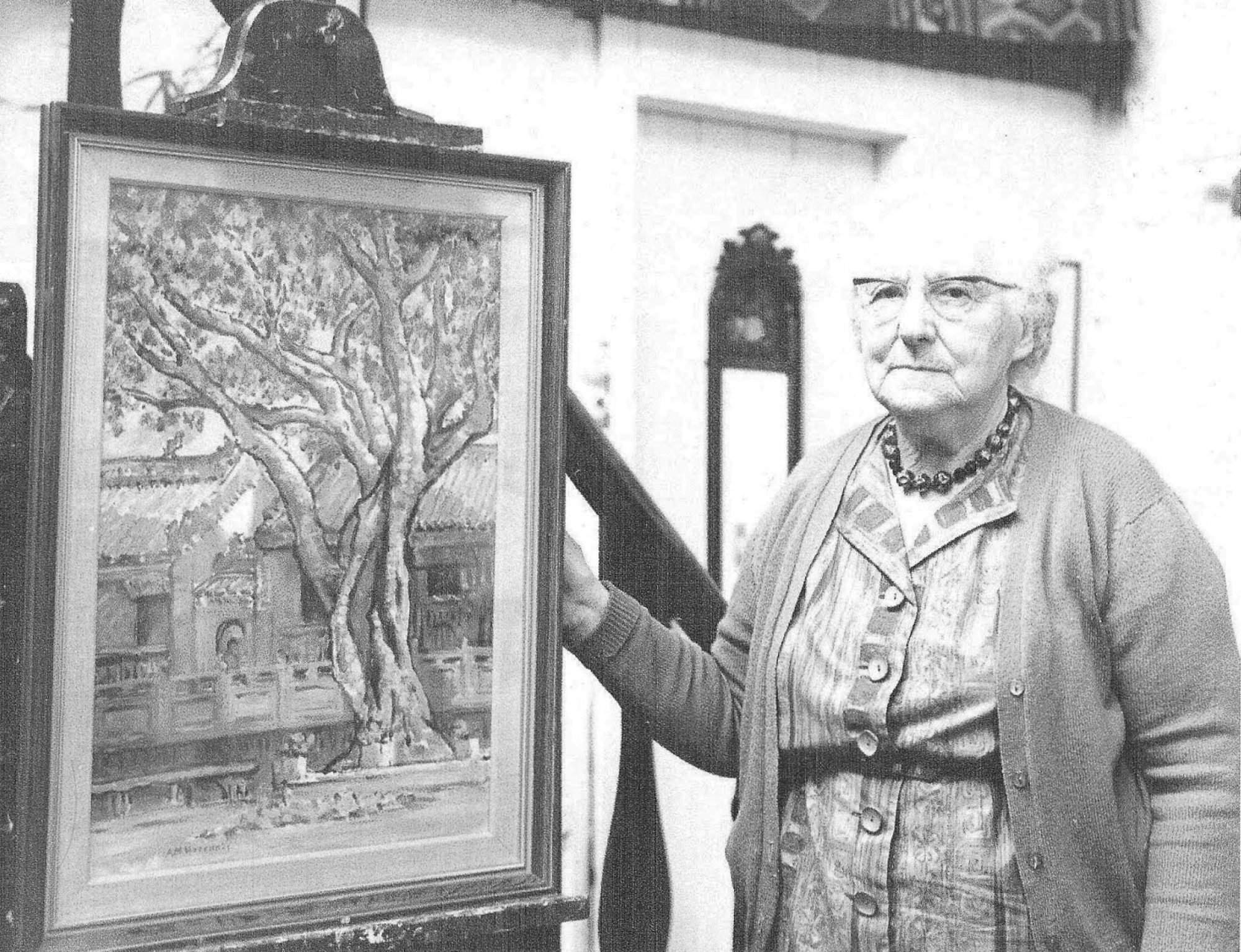

Under Burns’ tutelage, her landscapes appear almost like embroidered textiles of vivid, juxtaposed colours. Painting ran in the family – Hotchkis had been encouraged to study art, as had her three sisters, who all preceded her to both Glasgow and Edinburgh art schools.

After graduating, Hotchkis, at the suggestion of Burns, established her first studio in the charming town of Kirkcudbright, in Dumfries and Galloway, where there was an emergent colony of Scottish artists already living and appreciating the local landscapes, and cheap rents.

Hotchkis paid a peppercorn rent on a cottage and painted local scenes. She exhibited in Glasgow, Edinburgh and London.

But, after a decade in Kirkcudbright, she developed a touch of wanderlust.

Anna Hotchkis’ sister Catherine had moved to China in 1920 to work for the YWCA in Shenyang. Hotchkis visited in 1922 and found the country fascinating. She moved to Shanghai, where she continued to paint.

In a departure from her Kirkcudbright landscapes, she became interested in painting social scenes, depicting the often harsh life of the Chinese around her.

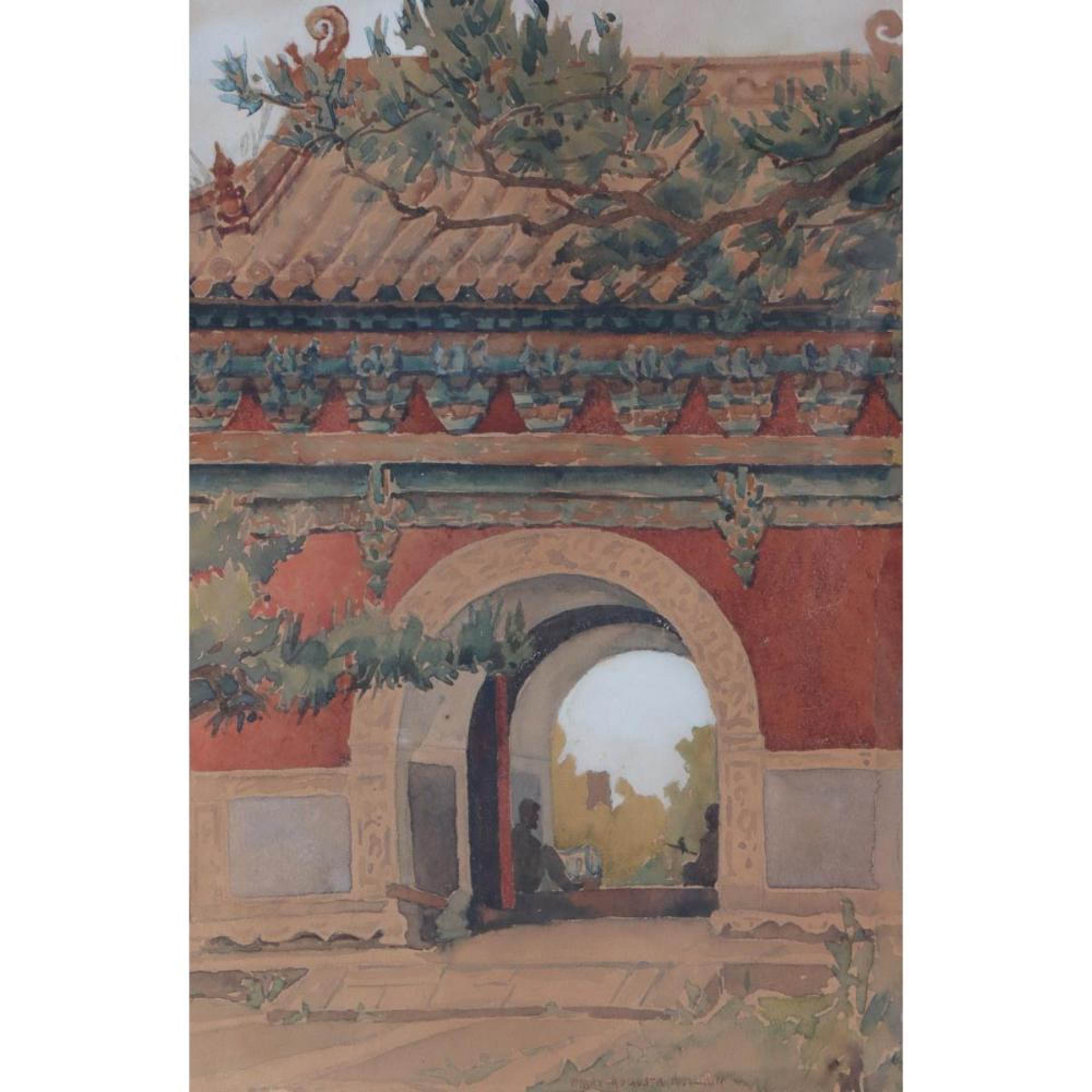

While painting child workers at a Shanghai cotton factory – where conditions were notoriously poor and horrific industrial injuries frequent – she caught a severe lung infection. Seeking drier air, she moved north to Beijing and got a job teaching art at Yenching University.

Her lung infection proved stubbornly persistent and, in the summer of 1924 Hotchkis was sent to convalesce in the popular seaside resort of Beidaihe, on China’s northeast coast.

In the summer, foreign Beijing essentially relocated to Beidaihe. The big Beijing and Tianjin department stores opened summer pop-up shops to keep the Foreign Colony supplied with everything from swimsuits to new gramophone records.

Milk was sourced from the nearby farms; the Greek-run Galatis Tobacconists opened a beachfront stall; the Tianjin Bakery ensured supplies of bread and pastries.

Fresh copies of the Peking and Tientsin Times arrived daily. And there was a lively cultural scene – chamber orchestras, light operettas, amateur dramatics and impromptu art exhibitions.

One such exhibition was organised by the Peking Institute of Fine Arts and included work by a Tianjin-based American artist. Hotchkis visited, was intrigued, and sought out the artist. And so she met Mary Mullikin, originally from Ohio and about 10 years older than Hotchkis. They were to be constant companions for the next 15 years.

Mullikin had studied with an impressive range of tutors. After a spell at the Art Academy of Cincinnati she left for Paris to study at the Académie Carmen under James Whistler, a great painter but reputedly poor teacher.

She then moved to London to study under Walter Crane, the celebrated English artist and illustrator. She returned to America and a teaching post at the Lasell Seminary for Young Women, near Boston.

Once there, she decided to stay and become a full-time artist.

In Beidaihe that summer, Hotchkis and Mullikin hit it off straight away: both unmarried women who wanted to be professional artists, both with tales to tell of the internationally renowned artists who had influenced them – Burns, Whistler, Crane – and who both shared a love of China.

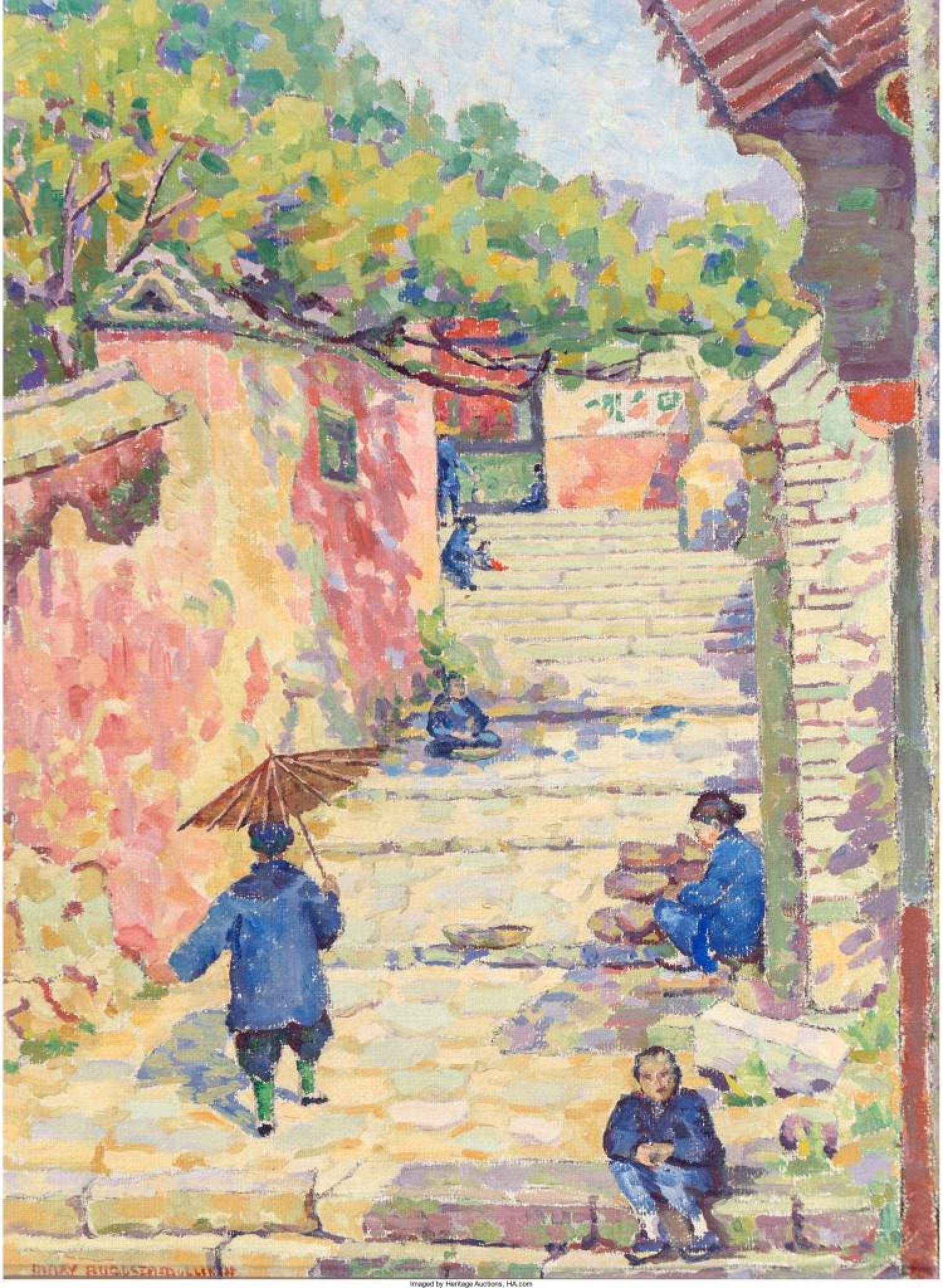

For more than a decade, Hotchkis and Mullikin travelled extensively together. In 1927 the pair visited Japan and Korea.

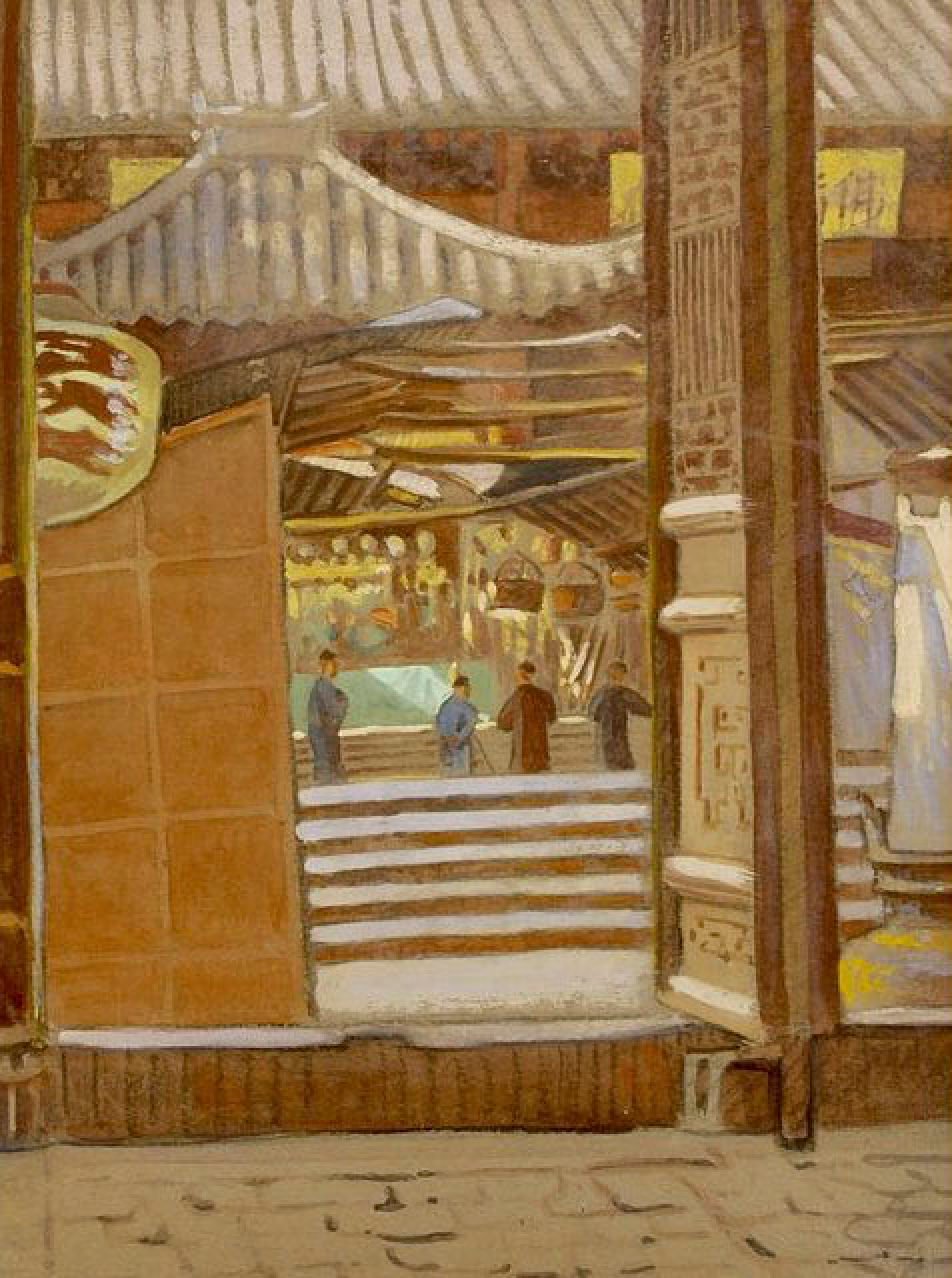

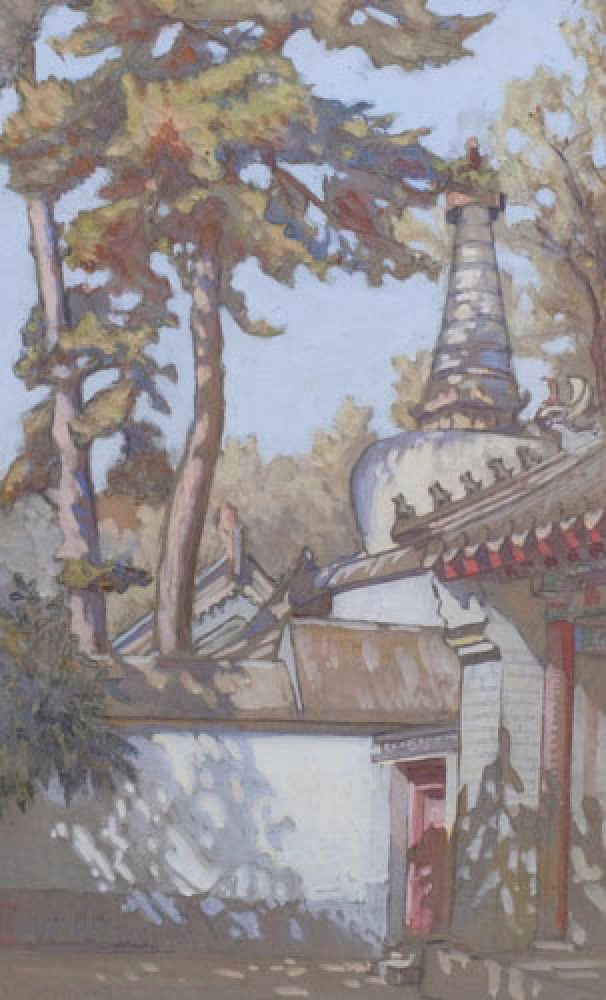

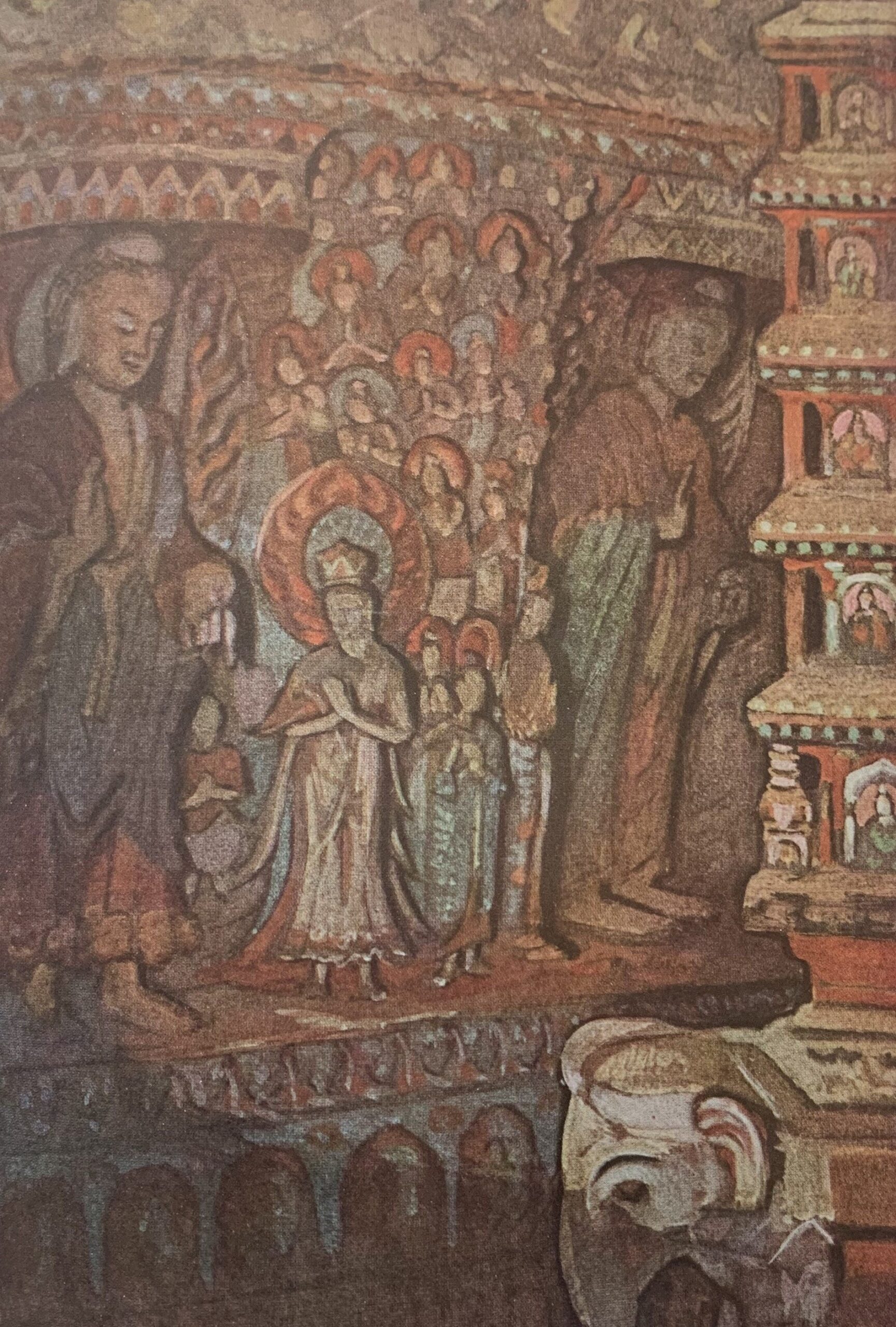

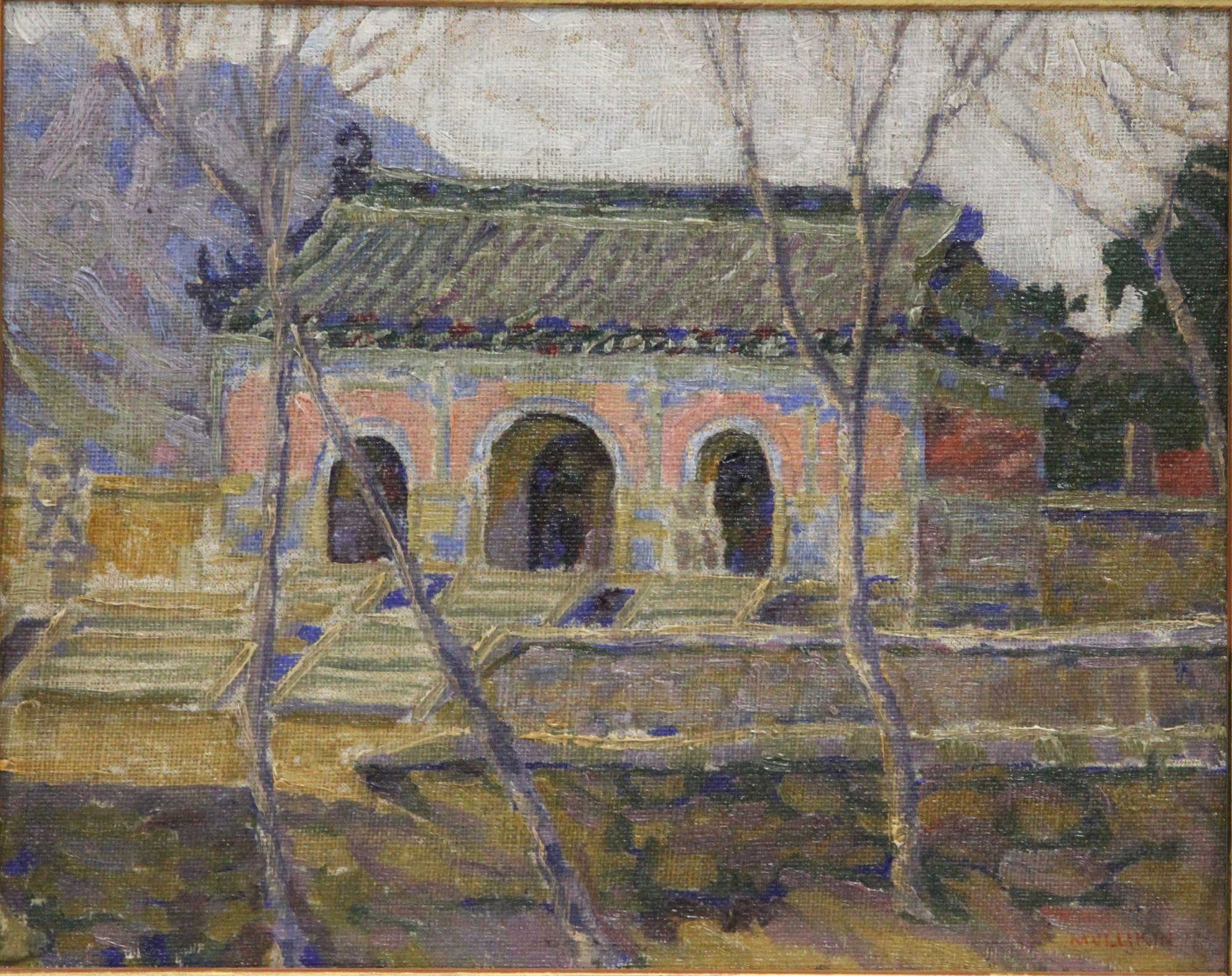

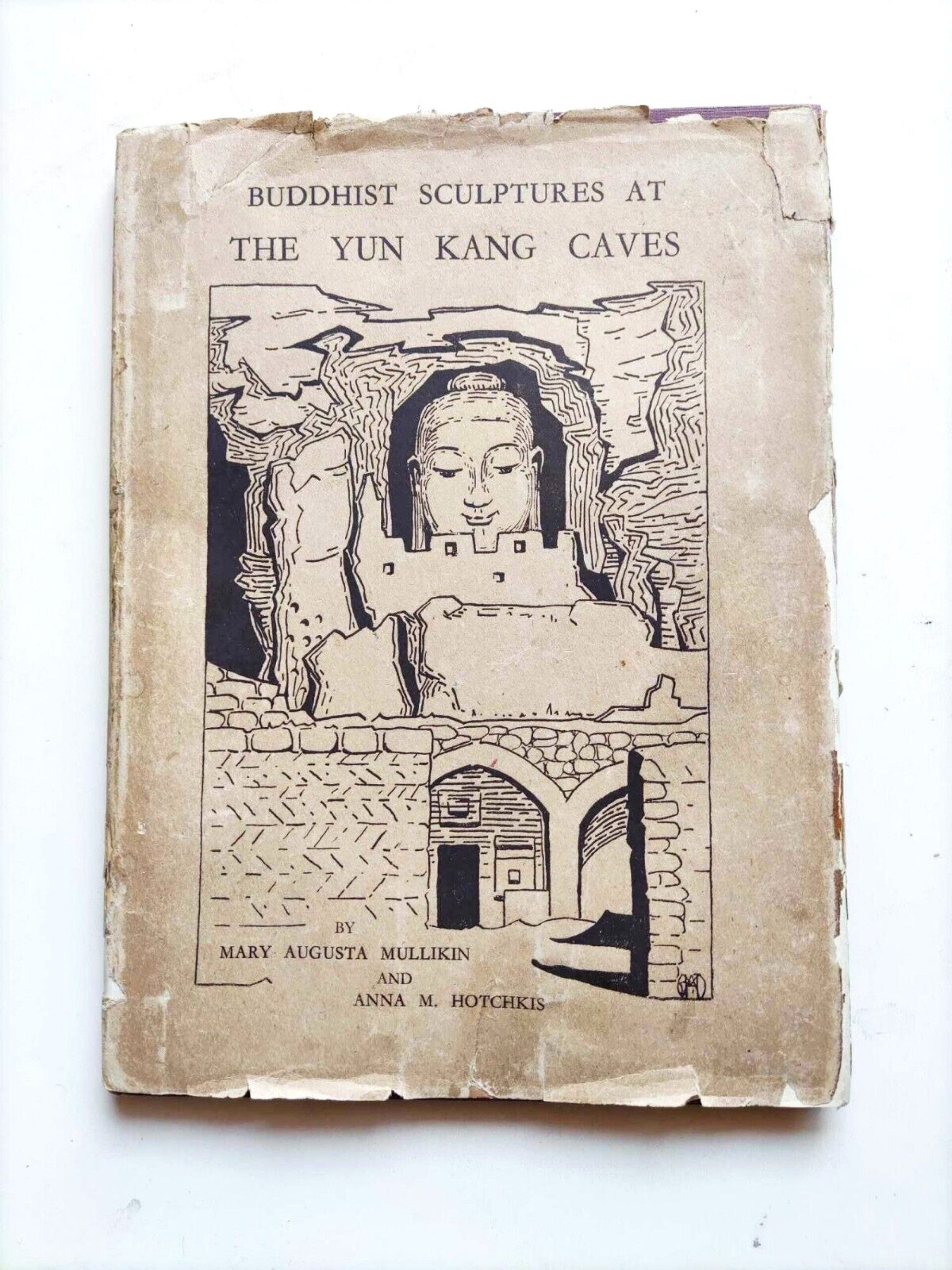

A few years later, they took what would be the first of several trips to the Yungang Grottoes, ancient Buddhist temples built during the Northern Wei dynasty (AD386-535) near Datong, in Shanxi province. They spent their time painting and sketching.

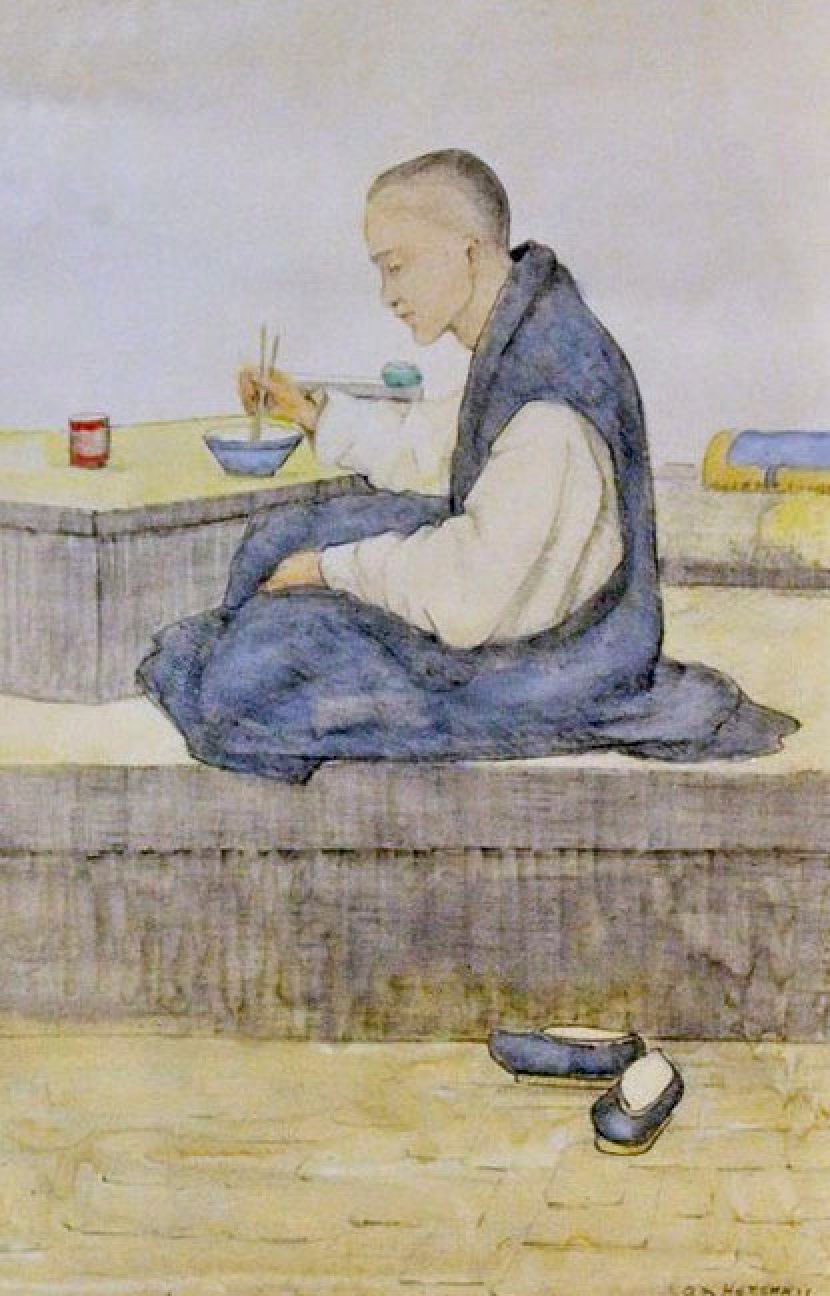

They stayed in a temple that had been turned into a hastily improvised hotel, but that still had a hall full of constantly chanting monks. Hotchkis told The Guardian newspaper that the lady artists and the devout monks studiously ignored each other’s presence.

Mullikin was always keen to do illustrated texts having studied under the master of book illustration, Walter Crane, in London. And so their trips to the Yungang Grottoes led to a book with text and sketches by Mullikin and artwork by Hotchkis – Buddhist Sculptures at the Yun Kang Caves.

Vetch’s Librairie Française was patronised by everyone in the Foreign Colony and his shelves of locally published and imported books and journals were seen as a lifeline for serious students of China in Beijing.

One critic for Parnassus, a major journal for the arts and aesthetics between the wars, noted that the book would be most “serviceable to the many visitors who come to these great monuments of early Buddhism”.

These newly adventurous tourists exploring China’s hinterland were just the market Hotchkis and Mullikin (as well as Vetch’s bookshop) were targeting, from whom they might earn a decent income, selling their landscapes and attracting portraiture clients.

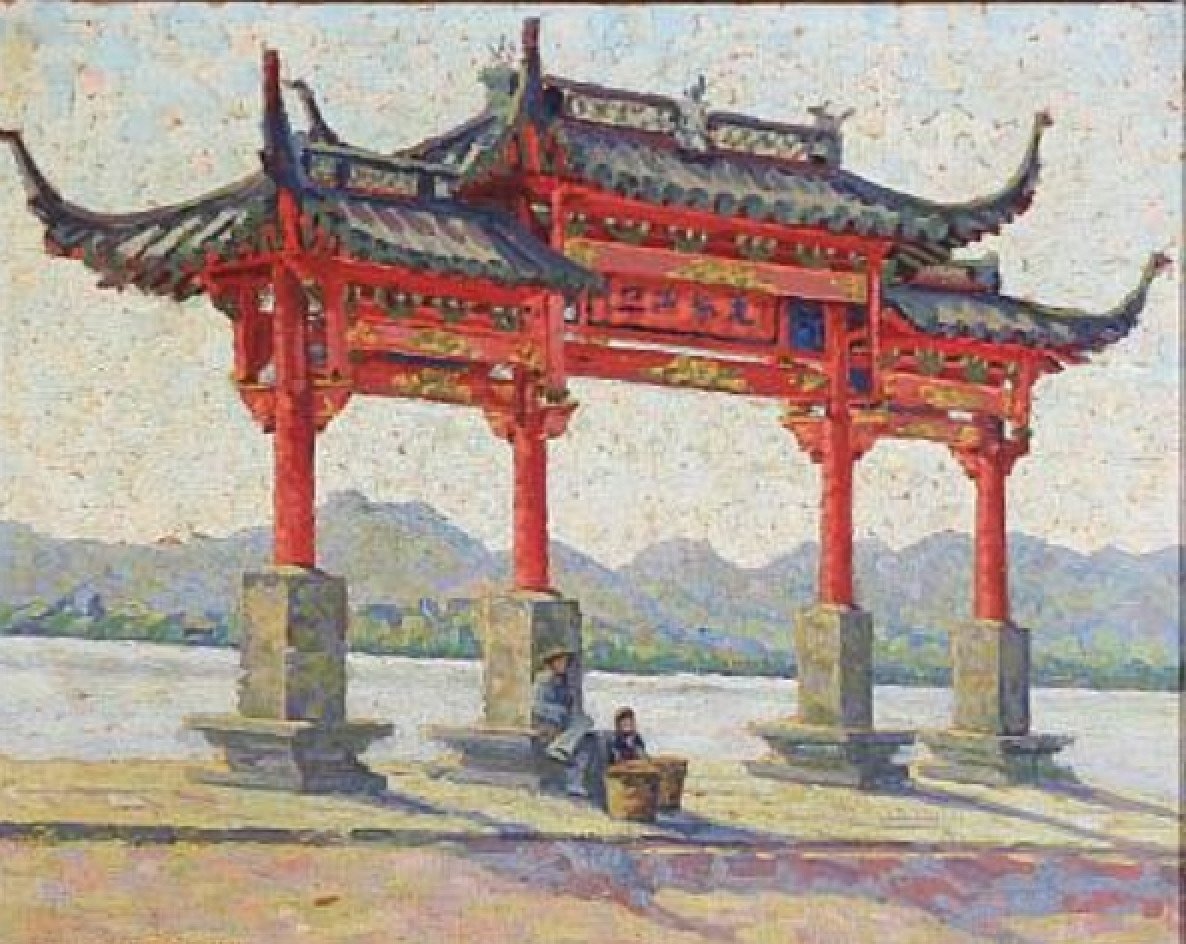

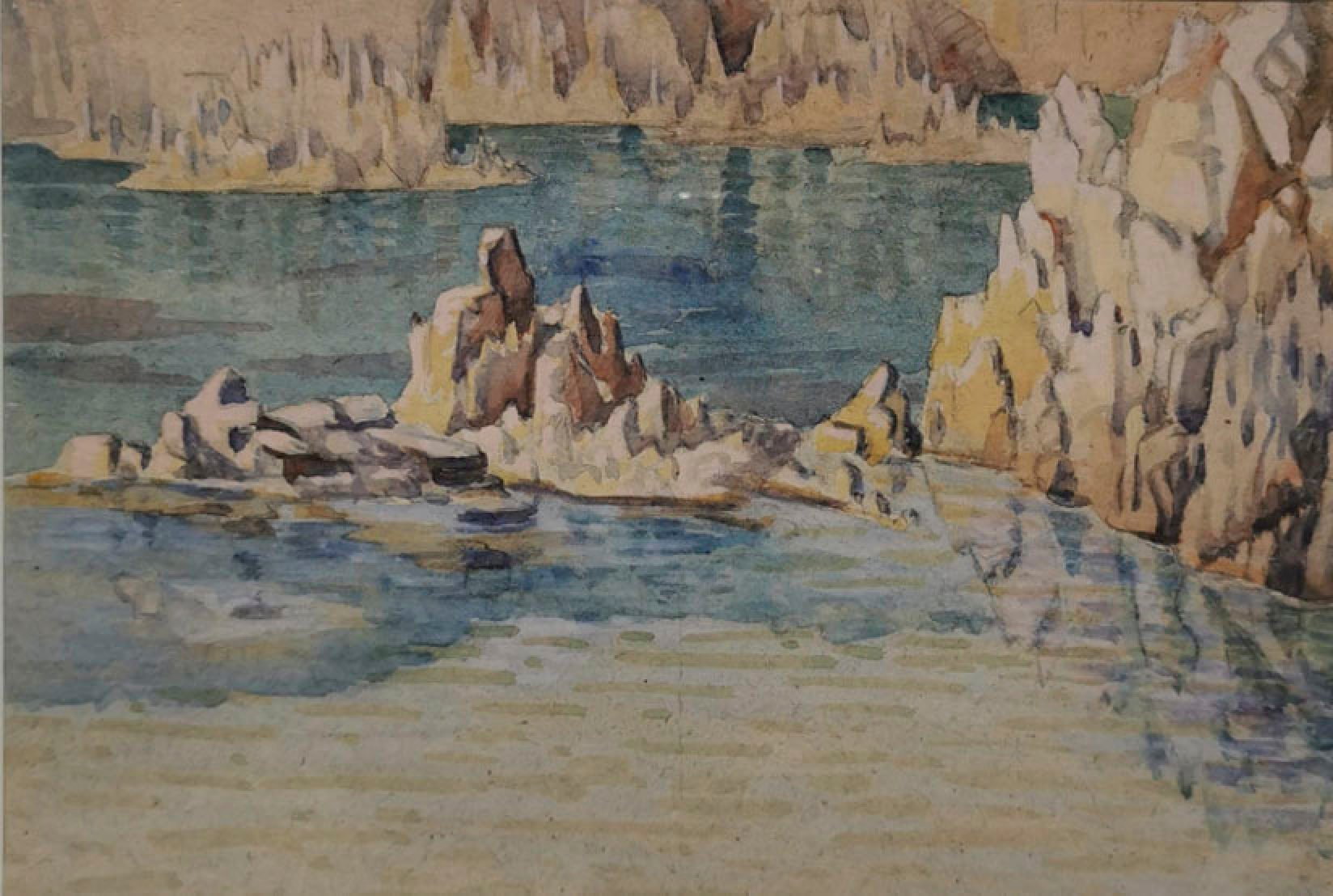

The pair continued to travel, taking painting trips to Hangzhou and the famed West Lake, as well as to Putuoshan, an island in Zhejiang province and a noted site of Chinese Buddhism.

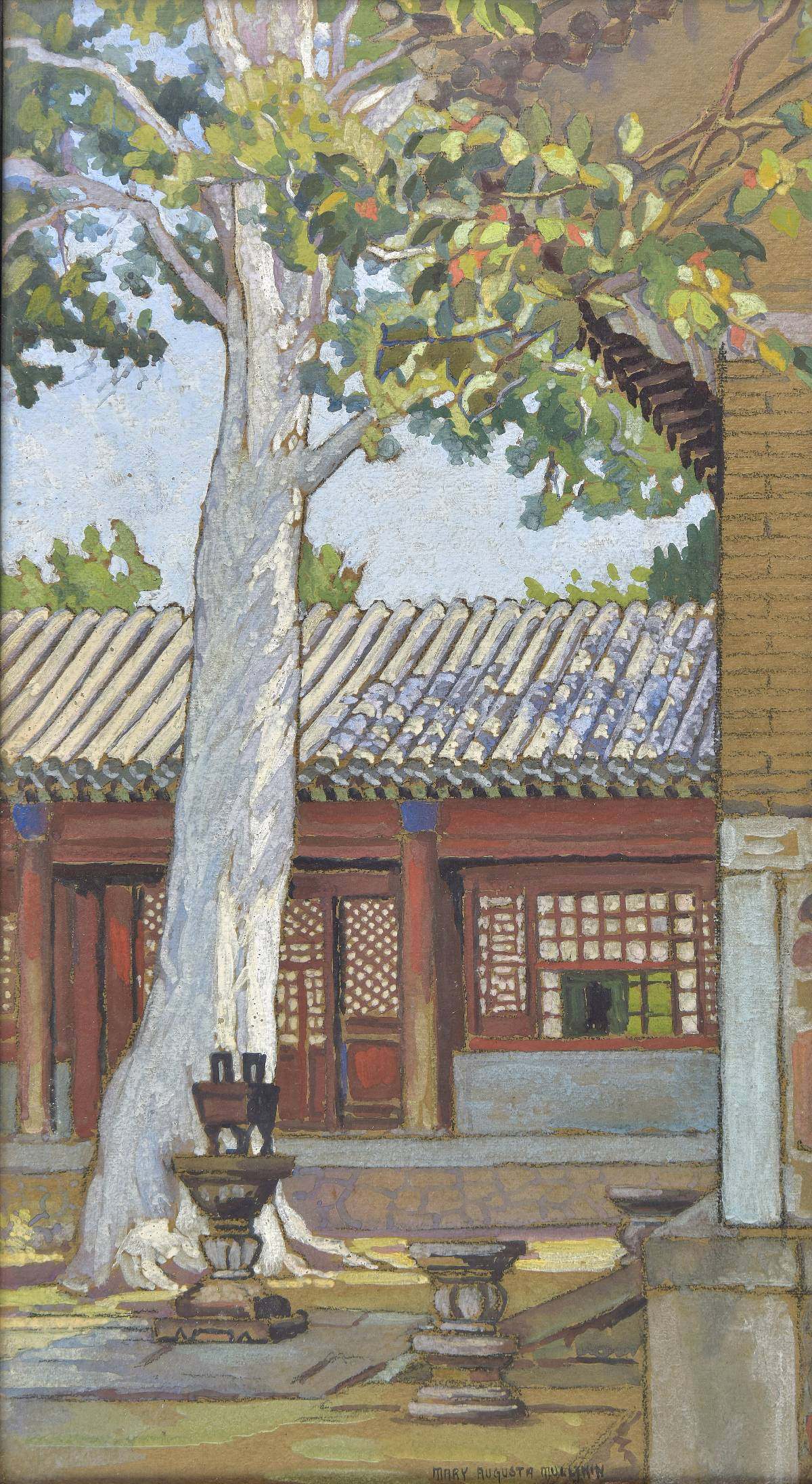

Painting scenes of Beijing, selling to tourists and local members of the Foreign Colony, as well as book sales, meant Hotchkis and Mullikin could establish themselves.

Light and airy with high ceilings and an internal courtyard in which to work in summer, her Xiehe Hutong space became workshop, gallery, salesroom, art salon and home. Mullikin moved in and the two artists shared the space.

They soon began to attract a wider clientele – tourists on the Grand Eastern Tour and even soldiers stationed in the foreign legations nearby looking for portraits in uniform.

They also started to be noticed by galleries in Europe and North America. Hotchkis exhibited in London’s Brook Street Gallery, which at that time specialised in images of China and the Far East. Mullikin exhibited regularly in Tianjin, where she was well known, and in various New York and East Coast galleries.

The success of one seemed to spur interest in the other – Hotchkis exhibited in Los Angeles and Washington’s Corcoran Gallery, while Mullikin had her own shows in London at the Brook Street Gallery.

This involved travelling over pretty much all of China at a time of bandit rampages as well as various epidemics. Shandong, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Sichuan, Zhejiang, Anhui, Hunan and Henan provinces all had to be covered.

The trip took its toll – travel options were often little more than donkeys or carts and accommodation was usually basic, with banditry constantly rumbling in the background.

Hotchkis, 50, suffered heart strain. Mullikin, now in her sixties, suffered illnesses that would plague her for the rest of her life. But they persisted and visited all nine sites.

And then Japan invaded.

The chaos of war separated Hotchkis and Mullikin. In July 1937, the Japanese attacked Beijing and Tianjin simultaneously. Mullikin wrote in her diary: “Friday June 15, 1938. Last night for two hours awful sounds of raging heathens filled the air […] Some estimated there were 50,000 voices, ‘Kill the Foreign Devil! Kill, kill, kill!’ They yelled till it seemed hell was let loose.”

Mullikin was stranded in Japanese-occupied Tianjin caring for her sick sister. Life became worse when their home was commandeered by the Japanese army. They were forced to move in with Swiss friends. Most of Mullikin’s collection of paintings was lost in the tumult.

Mullikin made some money painting portraits of local Tianjin residents’ Chinese ancestors from old photographs. The sisters remained trapped in Tianjin until the end of the war.

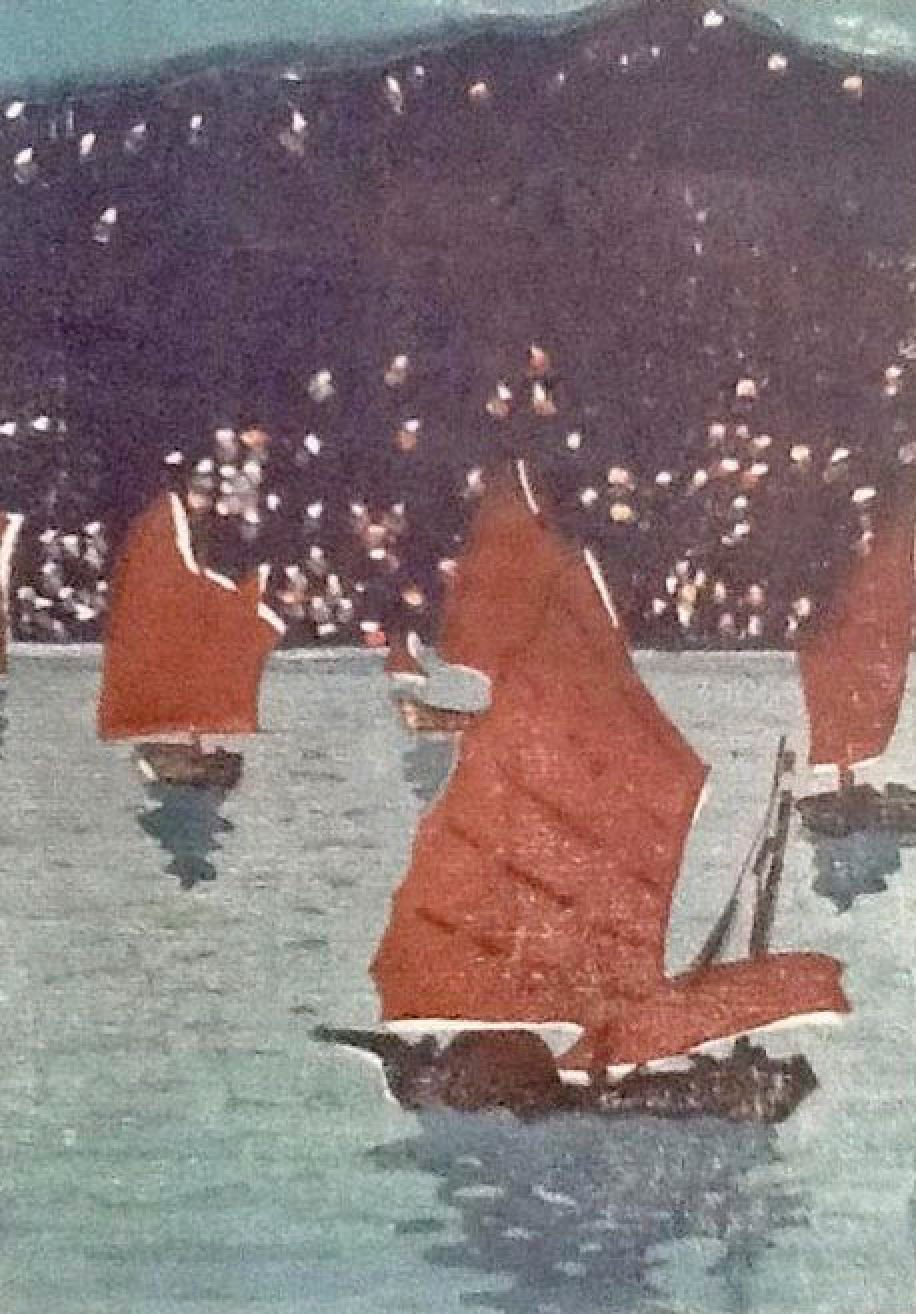

Hotchkis had managed to leave occupied Beijing around Christmas 1937 and get back to Kirkcudbright. It was a five-month trip via Hong Kong, Sri Lanka, India and Iraq to Greece.

There, she managed to find a passenger ship to Istanbul, then a cargo ship to Venice, standing all the way on the night train to Paris, then boat train to London and finally a long, war-disrupted train north to Scotland.

Like Mullikin, Hotchkis lost many paintings in the scramble to evacuate, but she did manage to hide their manuscript and artwork for their planned book on China’s nine sacred mountains.

Anna Hotchkis and Mary Mullikin never met again.

After the war, Mullikin accompanied a niece in the diplomatic service to Nairobi, Kenya, where she continued to paint well into her seventies.

Hotchkis also began to travel again after the war, in Europe and to the US. She made two trips to Hong Kong where, in the 1950s, Vetch was running Hong Kong University Press and, after retiring, became a partner in a small Hong Kong publishing company, Vetch and Lee, with offices on Queen’s Road Central.

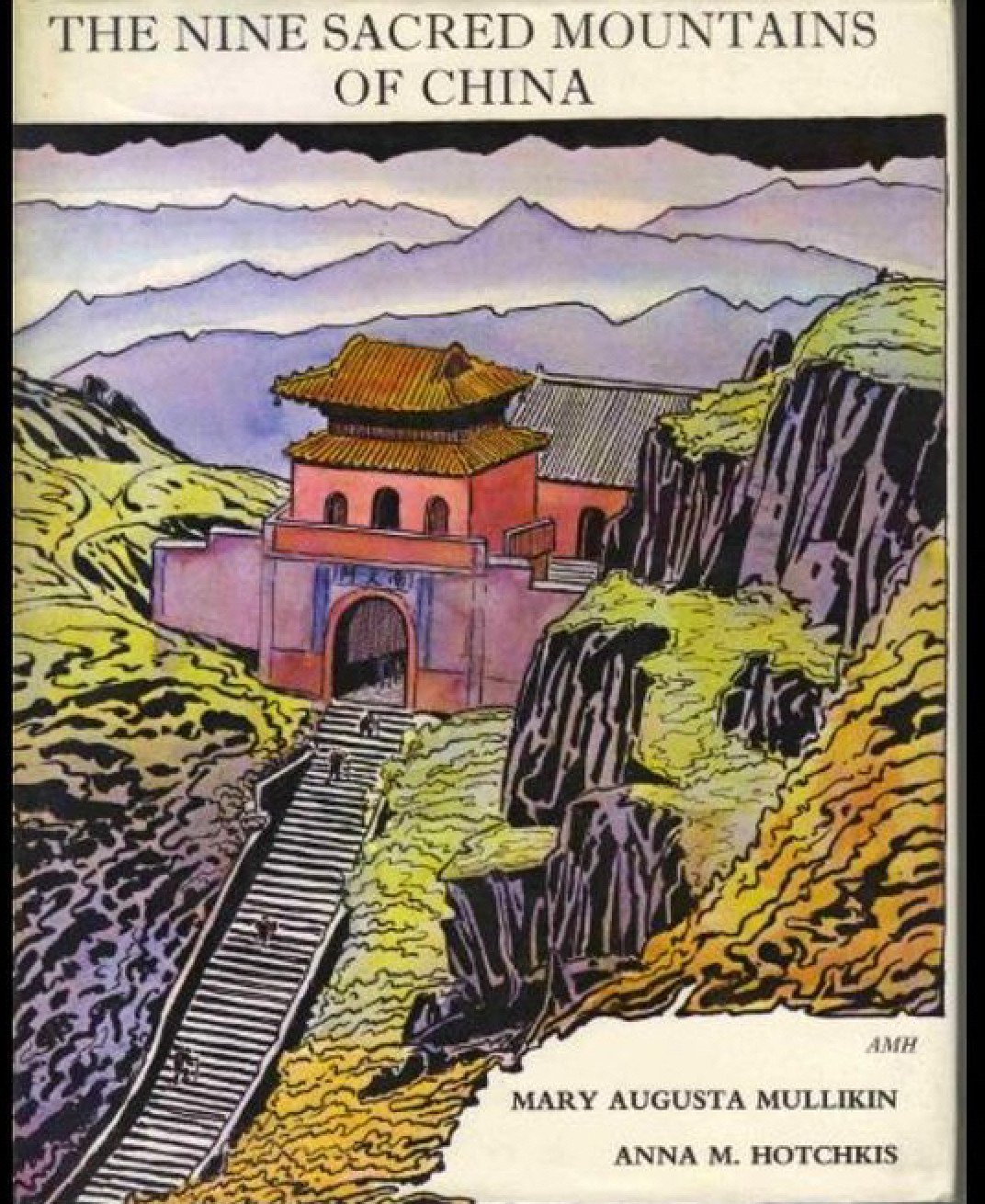

Hotchkis, visiting the city, could think of nobody else except Vetch who she would want to publish The Nine Sacred Mountains of China: An Illustrated Record of Pilgrimages Made in the Years 1935-1936.

And so in 1973, the book was finally published, 37 years after the two women had traversed China to visit, record and paint all of the country’s most sacred mountains.

Mullikin never saw the book completed. Having returned to the US, she died in Texas, in 1964, aged 89.

Hotchkis died in Kirkcudbright in 1984, having lived to 99 and still being a member in good standing of the Dumfries and Galloway Fine Art Society.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content