One of Australia’s most internationally renowned artists recast Aboriginal kitsch as the stuff of high art

No one inconsequential was ever called Destiny. For the past three decades until her death last month at the age of sixty-eight, Destiny Deacon plied her trade as an urban Indigenous Australian contemporary artist with no precedent or female role model in her generation. Nor were there any precursors for her work, which creatively reused the mass-produced, borderline racist ephemera she called ‘Koori kitsch’ or Aboriginalia, discarded in charity shops in the inner cities by nervous owners in the 1980s. At the height of these objects’ production in the 1950s and 60s, a range of utilitarian household items including ceramics and tableware were imprinted with visons of the Other – dusky maidens, plump bush babies and variations of the iconic One Pound Jimmy, the quintessential ‘noble savage’. At once popular representations of Australia’s first people – indeed, the only representations in wide circulation – and the artefacts of racism, Destiny collected them assiduously – perversely, at the start – and later upcycled them as art.

Having inherited a keen sense of justice from her activist mother Eleanor Harding, Destiny was politicised in the foment of the Aboriginal rights movement during the 1960s and 70s. She came to art in her thirties, after studying political science at the University of Melbourne and later stints as a teacher and public servant. It’s evident that in the arts she found something of a refuge for her political activism – which never waned – and which might have been stifled elsewhere. With characteristic humour and a highly developed sense of the ridiculous, Destiny talked back to power, institutional racism, patriarchy and the nation state through her art, but also mined universal themes which spoke more broadly to an international public. “I like to think there’s a laugh and a tear in each picture”, she said about her exhibition Walk & Don’t Look Blak at MCA Sydney in 2004.

Destiny was single-minded and sometimes obsessive when an idea took hold. In another 2004 interview she described the challenge of being an artist, one that confronted her every day on waking, breaking it down to its simplest terms: ‘I think to myself: you’ve gotta make an image that no one’s done before’. Indeed, nobody had conceived of the things she dreamed up, of using unwanted black dolls to enact racial and gender politics, exposing the power differential and structural inequality that exists in Australia. Black dolls were cast as actors in scenarios she, the puppetmaster, staged and plotted on the floor of her lounge in the inner suburb of Brunswick. That she regarded the unwanted black dolls as human – or at least metaphorically Aboriginal – is obvious; she frequently spoke of ‘rescuing’ or saving the ‘dollies’, as she called them. The scenes or vignettes she directed, occasionally with live subjects – her family and friends – captured the joy and the melancholy of the everyday.

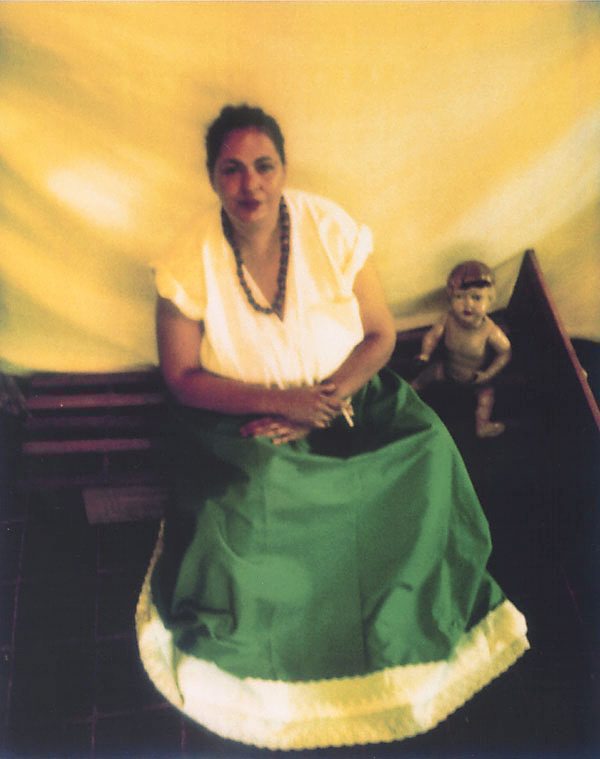

I smile involuntarily when I see her artwork in a gallery collection, and not simply because I knew and loved her (as many, many people did). I feel as if I am in a dialogue, part of a conversation, because her work speaks so clearly to me, and to other blackfellas. Often, her work makes you laugh. But then meaning in her work is encrypted; what seems simple or plain, is nothing of the sort. The only self-portrait Destiny ever produced – or made public – is one of a sequence of images she produced that draw on the history of art. In it, she recreates the pose and mise-en-scene of Frida Kahlo’s 1937 self-portrait Me and My Doll, in which the iconic Mexican artist sits on the frame of her bed, coldly distant from what would seem the natural object of her affection: a doll, onto which Kahlo is said to have displaced her anguish at not being able to carry a child full-term (she suffered three miscarriages). In hommage, Me and Virginia’s doll (Me and Carol) (1997), Destiny does not reproduce the gravity and existential longing of Kahlo’s image. The spooky (white) doll alongside Destiny is identified in the title as belonging to her partner, Virginia Fraser, a collaborator and fellow artist who, until her death three years ago, was deeply enmeshed in Destiny’s process. Instead, Destiny smiles wryly, almost conspiratorially, as if pre-empting the viewer’s presumably heteronormative assumptions about women and the reproductive choices they make – or don’t (as the case may be). It’s a game she’s fixed, and she holds all the cards.

Destiny steadfastly refused to be shamed for her lived experience of Aboriginality. She was raised in the working-class Melbourne suburbs of Port Melbourne and Fitzroy, the latter both a hub for the local Aboriginal community and, as such, a beacon for Indigenous people from all over Australia. She felt no compulsion to perform Aboriginality, and no affection for the bush – the inland of this vast continent and an imaginary where we are said to belong. It was Destiny who originated the inclusive, now widely used term blak to describe urban Aboriginal identities. In an act of self-definition, she inverted a term of racist abuse once in wide circulation, ‘black’, by literally taking the ‘c’ out. Devoid of those connotations, blak expressed something new but is also a neat, four-letter word, with the same power and declamatory effect as a profanity. Destiny used it in the titles of her exhibitions and artworks, including the last major commission for the 2024 Biennale of Sydney, Blak Bay. Unsurprisingly, blak entered the vernacular. Ellen van Neerven acknowledged Destiny’s cultural impact in the laudatory poem ‘Portrait of Destiny’ (2020):

Throughout much of her extraordinary 30-year career, Destiny had to make it up as she went along – one of the occupational hazards of being an artist who possesses a singular vision. She was also an out lesbian who lived openly at a time when homophobic abuse and violence was rampant. Destiny prepared the way for those who would follow, and did so consciously. Every Indigenous artist working in an urban context today and particularly those who identify as blak and queer benefit from what Destiny had to do. She made art that challenged those who patrol its outer limits (until she could win them over) and whose idiosyncratic sense of humour and hypercritical eye – which she trained on the tragicomic aspects of everyday life – found her work an international audience. It sounds trite, but I am utterly convinced there will never be another like her.

Daniel Browning is a First Nations journalist, radio broadcaster and sound artist

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content