Josh Anderson has been a Black Keys fan for over a decade. He fell in love with the band as a high schooler in 2007. But in April, when tickets for the blues-rock revivalists’ North American arena tour went on sale, Anderson realized he wouldn’t be attending. The prices were simply too high.

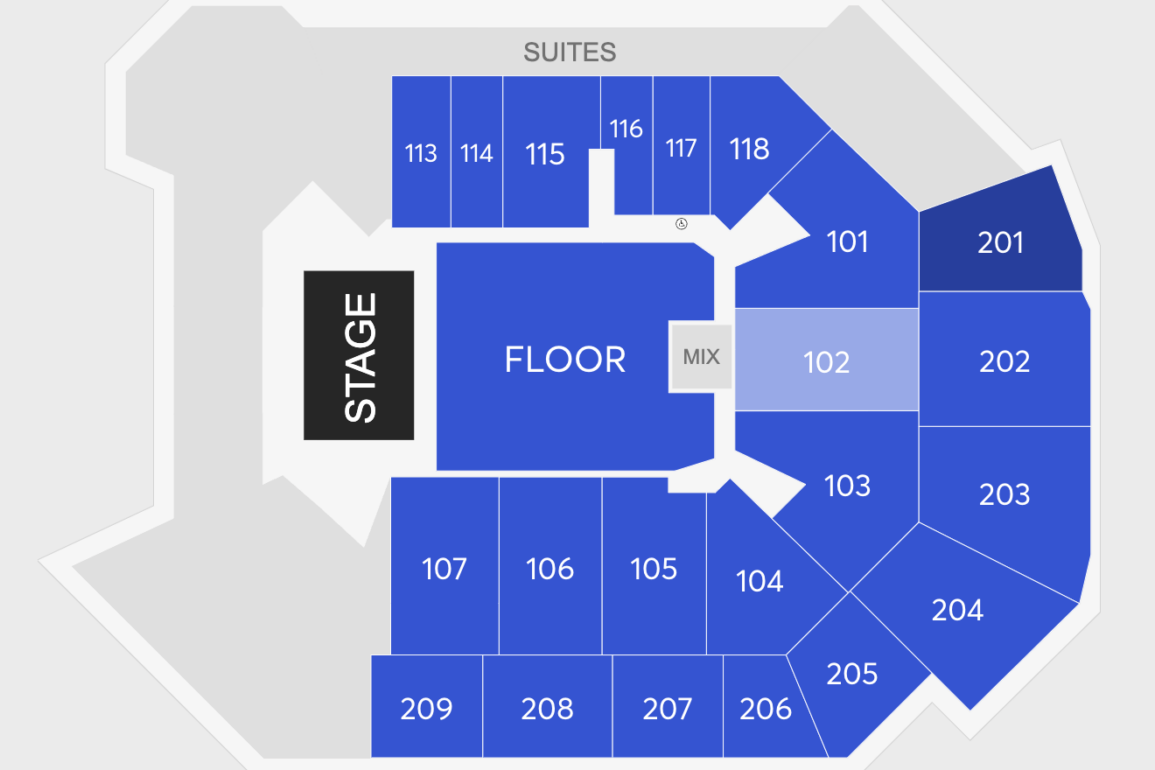

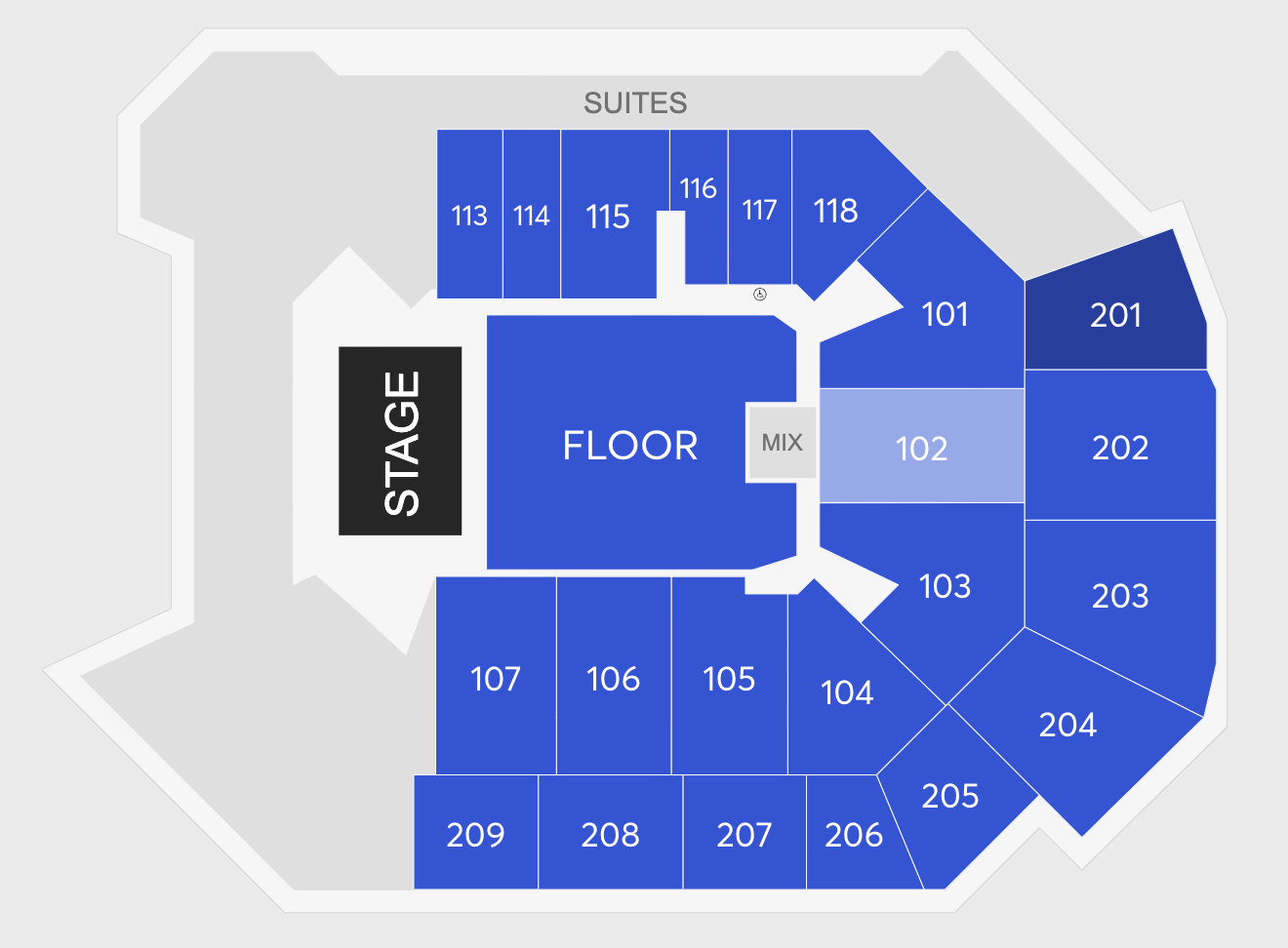

“I’m in Peoria, so St. Louis and Chicago, it’s not too big a drive,” says Anderson, who is 32 and works for a medical supply company. “But between that and pricing and parking, it’s hard to justify even if you love the band. I wasn’t seeing anything lower than like $100 for United Center. I just glanced and was like, ‘Oh, that’s a no.’”

Judging from anemic ticket sales and plenty of anecdotal accounts, Anderson isn’t the only fan who balked at three-figure prices. On May 24, the Black Keys quietly canceled their entire arena tour, leaving confused fans scrambling for answers. Days later, the band put out a euphemistic statement, saying they planned to announce revised tour dates “that will enable us to offer a similarly exciting, intimate experience for both fans and the band.” (In blunter terms: smaller venues.)

“Obviously, they made a decision that it wasn’t going to be a good experience for anybody,” says Jordan Kurland, founding partner at Brilliant Corners Artist Management, who manages acts like New Pornographers and Death Cab For Cutie. “Look, it’s a bummer that it was such a public thing. But that’s the world we live in. Seating charts are available online.”

Kurland adds, “I would also commend them for hearing the fans and saying, ‘This is not where the fans want to see us. We thought it might be. It’s not. We have the opportunity to reset.’”

The Ohio-bred duo isn’t the only major act facing these questions. Despite the outlier success of unicorns like Taylor Swift, the post-lockdown touring boom has cooled, and a surprising number of big-tent artists are struggling to sell their 2024 arena tours. Fans have shared screenshots of wildly undersold sections for dates on Charli XCX’s joint fall tour with Troye Sivan, though a rep for Charli says multiple dates have sold out and sales are at 70% across the board. Porter Robinson’s “5-continent world tour” is faring even worse, with dates in cities like Orlando displaying pretty much entire sections of available inventory.

And a week after the Black Keys debacle, Jennifer Lopez, who had already canceled seven dates of her summer tour and renamed it “This Is Me… Live | The Greatest Hits” to redirect the focus from her new album to her back catalog, scrapped her entire tour. “I am completely heartsick and devastated about letting you down,” JLo wrote in a statement to fans.

Sources say Lopez made the decision for personal reasons (her marriage to Ben Affleck is rumored to be in trouble), though weak ticket sales probably didn’t help. As one booking agent, who is not affiliated with JLo, puts it, “If every venue was selling out, I think it’d be more likely that the tour would still be happening.”

“Some of the tours aren’t really doing so hot right now,” says Tony, a music fan in the midwest who runs the Twitter account @UnderFaceValue, helping fans find cheap tickets for undersold concerts. “Jennifer Lopez. The second round of Justin Timberlake, in the fall. Kacey Musgraves. AJR. It’s market to market, but in a lot of cities, those shows have great availability.”

Welcome to the Summer of the Mysteriously Flopping Arena Tours. Why are so many tours struggling to sell seats? How is this kind of large-scale misjudgment possible with so much data available?

Experts say… well, it’s complicated.

Live Nation Entertainment says, in a statement provided to Stereogum: “Overall market data shows demand is strong—sales are up from last year with over 100 million tickets sold, even with fewer large stadium shows touring in 2024. Plus ticket sales for shows in arenas, amphitheaters, theaters, and clubs are up double digits year-over-year. Every year some events naturally fall off for various reasons, and in 2024 across all venue types we’ve seen a 4 percent cancellation rate—which is flat to last year.”

Black Keys drummer Patrick Carney put it more concisely in a cryptic early-morning tweet: “We got fucked.”

“The last great arena rock band”

Let’s start with the Black Keys situation. (The band’s reps did not respond to a request for comment for this piece.) After spending the early aughts working their way up the club circuit, the band has been a major touring attraction for nearly 15 years—since the crossover success of 2010’s Brothers (featuring surprise hit “Tighten Up”) and 2011’s El Camino, the latter of which had them headlining arenas for the first time.

Given the scarcity of rock bands formed after Y2K at that level, the duo holds a rarefied place in the industry.

“In a lot of ways, the Black Keys feel like almost the last great arena rock band,” says Eric Renner Brown, a senior editor at Billboard who previously reported on live music for the trade publication Pollstar. “This is perhaps a case where people across the industry feel especially invested in this band succeeding.”

The band’s would-be 31-date tour was produced by Live Nation, which has a vested interest in getting big artists into the biggest possible venues. As ever, the capitalist dream of unending growth bumps up against reality.

“Black Keys kind of took the fall for a lot of people that aren’t selling well,” Tony, who prefers to be identified by first name only because he works in the ticketing industry, adds. “But Black Keys were really, really poor. They were playing the Louisville Cardinals basketball arena, which is one of the biggest basketball arenas in North America in a relatively small market. It was just so poorly sold.”

Why would they book such oversized venues? To some extent, “it’s just pure greed,” says a booking agent with many years of experience, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Live Nation needs to fill these big rooms, so they make aggressive offers and then the agents and managers take them. Some of it is, it’s hard to go backwards. If you’ve ever done arena tours before, it’s very difficult to take a step back and make less money on a smaller tour. No one wants to present that to a manager or band.

“There’s certain agents that have a track record of just kinda killing bands,” the agent adds. “They fire the agents at a smaller agency, it goes to a bigger agency, and they just cram it down the throat of these promoters, and there’s a frenzy in the promoter game. Everyone wants a piece of it, and the tour deals get more and more aggressive. Then they price the tickets too high and they just don’t sell.”

Though he stresses that he doesn’t know all the specifics of the Black Keys’ situation, Kurland tells Stereogum, “The reality is that when a big promoter has a deal with a venue, they need to put shows in that venue and they make money on a lot of the ancillaries. Did Live Nation do a tour deal with the Black Keys for this tour? If so, these are probably the venues that they recommended. Did they pressure them? I have no idea. Was it more profitable to go into these rooms vs. smaller rooms? I’m sure that was the case.”

So why did the tour struggle to sell? Theories abound. For one thing, the band falls into an in-between space: no longer in their career peak, but not enough of a legacy act to mount a big nostalgia tour. Their fanbase is aging — and busy parenting, in many cases — and without a recent hit like “Lonely Boy,” the retro-fueled band may not be bringing in younger fans. (You’re telling me Gen Z isn’t going crazy for an album of hill country blues covers??) Their new record, Ohio Players — which peaked at #26 on the Billboard 200 — also underwhelmed commercial expectations.

“With this album, they had some songs co-written with Beck. They were maybe trying to reclaim some radio glory from 10 or 15 years ago,” says Brown. “When they were booking this tour, they hadn’t started rolling out the singles or the album yet. Maybe they were thinking they would be coming into that tour announcement from a position of strength.” (Similarly, JLo’s tour was booked ahead of her new album, This Is Me… Now. The album has gotten middling reviews and debuted at #38 on the Billboard 200, her first studio effort to miss the Top 20.)

Brown adds, “I do think they’re an artist that can fill those rooms still. I think the demand is there in terms of people who want to see Black Keys. But perhaps at that price point, the demand was not there.”

Ostensibly, agents and promoters should have access to data that can give them a better sense of demand. But they often place outsized importance on raw streaming numbers.

“The data is very confusing,” says the anonymous booking agent. “There’s a lot of passive listeners for data. You can have millions upon millions of streams, but that doesn’t mean it’s gonna turn into tickets. The opposite is, there are some artists who don’t have many streams at all and they can sell like 2,000, 3,000 tickets.”

Streaming numbers may be part of the reason Porter Robinson is headlining undersold arenas and amphitheaters, the biggest venues he’s played to date as a headliner. The DJ-slash-electronic pop guru boasts hundreds of millions of Spotify streams, but EDM festivals play such a big role in his touring ecosystem that it’s unclear if he can translate that energy to traditional venues. His tickets are currently going as low as $25 on the secondary market.

“Revenge spending is over”

It’s worth noting that the Black Keys have released four albums since returning from hiatus in 2019, and toured arenas as recently as 2022. This may be a case of oversaturating the market.

The band’s 2019 and 2022 arena runs weren’t exactly sold out. In between, the band left their longtime manager in 2021, signing with Irving Azoff and Steve Moir at Full Stop Management. Some sources speculate that Azoff, a former CEO of Ticketmaster, may have encouraged ambitious touring plans. On Thursday, Billboard reported that the group has now parted ways with Azoff and Moir. (The management company did not respond to a request for comment.)

“Essentially, you have some very big managers that are out of touch with the granular finesse and nuance of ticketing,” says another anonymous booking agent. “And they have these large expectations and they tell their agents what they want. And the agents are probably texting each other on the side, going, ‘This man is out of his fucking mind.’ But they do it anyway because, in the case of Black Keys, they’re not gonna challenge Irving Azoff.”

Which brings us to the question of timing. Two years ago, both demand and pricing were through the roof as fans rushed to return to live events after the lockdown blues. Today, “revenge spending is over,” Kurland says. “People [were] just spending money on experiences because we didn’t have that for two years. I think people are having to be more cautious with their money.”

“Coming out of COVID, there was so much pent-up demand for live concerts of any type,” says Brown. “I think a lot of decisions have been based on that demand. Now, things are starting to stabilize after that post-COVID touring bump. [In] 2022, there were people really excited to be going to concerts again. Maybe thought they wouldn’t be able to see their favorite band the Black Keys for many years. That might have given their team a sense that demand was a little bit higher than it was.”

Setting aside classic-rock dinosaurs with massive intergenerational appeal, the rock tours that are succeeding on the arena and/or stadium level these days tend to have clearly stated hooks—or “news pegs,” in the media parlance—to get fans excited.

The “reunion” peg, for instance, is big right now. Jane’s Addiction’s best-known lineup, Dave Navarro and all, is reuniting for their first tour in 14 years. Blink-182 made nice with Tom DeLonge and the band’s “classic lineup” enjoyed a successful comeback tour last year.

The “farewell tour” is also a tried-and-true approach — see: Elton John, Eagles, Jeff Lynne’s ELO, Cyndi Lauper — though it carries risks, like when the aging bad boys bidding adieu to rock are so old that they have to keep postponing their farewell tour due to injury and wind up trapped in some mid-farewell purgatory.

But legacy bands not quite ready to hang up their hats gravitate towards anniversary-driven nostalgia tours. Cognizant of round-number anniversaries, Green Day vowed to play Dookie and American Idiot in full on their current tour with Smashing Pumpkins and Rancid. Of course, Dookie wasn’t the only watershed pop-punk breakout of 1994; enter Weezer and their impending Blue Album 30th anniversary tour. As Stereogum’s own Chris DeVille put it, “Resistance is futile, elder millennials!”

“Nostalgia is in right now,” says Kurland, and he would know; he oversaw last year’s elder millennial nostalgia tour of the season, the Death Cab For Cutie/Postal Service double-header.

“It was 100 percent sold out,” Kurland says. “I think, if anything, we undershot it. But we were really cautious, based on what we saw in 2013, which is: people didn’t want to see the Postal Service in arenas on that tour. So we took that in mind on this tour and I think undershot it in some markets. It felt for us like, yeah, we didn’t do TD Garden in Boston and should have. Instead, we did two 5,000-cap shows that blew out. That would have been better than doing TD Garden and selling 6,000 tickets. You just don’t know.”

The eternal lesson: sometimes underestimating popular demand is less embarrassing than overestimating.

“Everyone wants to see those flashing lights”

One contributing factor to instability in the touring industry is the rising cost of… well, everything. It’s part of why ticket prices are so high; it’s also part of the reason some acts are backing out of touring commitments.

Bands at all levels have been sounding the alarm about this for years. In 2022, for instance, Animal Collective canceled European tour dates and explained, “We simply could not make a budget for this tour that did not lose money even if everything went as well as it could.”

Industry insiders say that’s not uncommon. “Everything is ridiculously expensive,” says a tour manager who works with major acts and asked not to be named. “There’s not enough gear for everyone to share, so the vendors are having to pay high amounts for equipment. A single bus for a six-week tour can cost $100,000. Multiple that by multiple buses, and then trucks, and then crews are at a minimum, so they’re getting top rate right now because there’s not enough crews.”

COVID, of course, exacerbated this crunch. “What happened after the pandemic is, everyone was ready to tour at once,” the tour manager says. “There’s not enough gear to cover all of that. A lot of bands have had to cancel tours because they don’t have gear or they couldn’t afford the gear,” the tour manager continued. “I was on a tour with somebody last year where we had to book a private jet because there were no buses available. For the first week of the tour, we had to charter planes.”

Acts are thus incentivized to book bigger venues to recoup the costs of touring. The catch-22 is that bigger venues necessitate more elaborate stage production, which makes for a more expensive tour.

“There’s the expectation to have that production,” says the tour manager. “If people went back to having just two trusses of lights and a P.A. and no frills, it was just about the music, they can afford to tour. But everyone wants to see those flashing lights. Everyone wants to see that video.”

“So much of the economics of these big tours is completely invisible to fans and consumers,” says Kevin Erickson, director of Future of Music Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group. “You can sell out a tour and come back in the red if there was a cost overrun or a miscalculation.”

For mid-level acts with sizable followings, these frustrations are compounded by a lack of suitable mid-sized venues.

“For a band that maybe has assessed its demand in the market to be in the 8K range or something for capacity, where are they going to go if that sort of venue doesn’t exist?” says Brown. “And if, say, the local theater that seats 3K or 4K can’t accommodate two or three nights, it can only put them for one night on the tour routing. That’s a real concern.”

“It’s capitalism at its best”

At the end of the day, it all comes back to price. The average ticket price for one of the top 100 tours rose from $91.86 to $122.84 between 2019 and 2023. Concerts are too damn expensive, and there’s a growing sense of consumer frustration with shows that cost as much as airline tickets.

Last year, this frustration boiled over after price tags for top tours like Beyoncé and Bruce Springsteen sometimes entered the thousands thanks to “dynamic pricing.” A bitter rift tore apart the Bruce fan community; some stans turned their backs on the Boss for betraying his working-class bonafides. Of course, Bruce and Beyoncé are big enough to shake off that backlash while mid-level acts suffer from their fans’ price sensitivity.

“Who can afford to go to multiple shows?” says the anonymous tour manager. “Two tickets to a show, you’re talking probably about $200 with fees and everything. You go to a meal around the show, you’re talking at least $100 or $200 for a nice dinner. Then you got parking and babysitters, then you add the VIP stuff to that and you want to make it a special night, you’re talking $500 to $1,000 a night for a couple to go out. It’s capitalism at its best.”

The result is a dynamic in which the rich shell out top dollar to see major acts while working-class fans grow increasingly disillusioned with the music industry.

“To justify going to a concert is unfortunately a pretty big decision for somebody like me,” says Josh Anderson, the Black Keys fan in Illinois. “It definitely hurts your heart a little bit when your favorite band is pricing you out, so to speak.”

Could the impending Department of Justice antitrust lawsuit to break up Ticketmaster and Live Nation help with prices? Maybe. “I’m worried that if it breaks apart, the loss in revenue that the venues are facing will be taken out of artists’ end,” says the anonymous booking agent.

Robert Smith of the Cure took a stand last year, publicly fighting with Ticketmaster to keep concert prices and fees reasonable, but few musicians have that kind of power and sway when it comes to pricing. Crucially, Smith not only kept Cure prices low but also took extreme measures to crack down on scalped tickets.

“If an artist who didn’t have access to the fan-to-fan resale system tried to do what Robert Smith did in terms of keeping tickets affordable, it would be millions and millions of additional dollars going to the resellers,” says Kevin Erickson.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content