You could tell Göksu Kunak’s performance was beginning because blue light started flickering against the faces of a shadowy mass of guests pulling out their phones. Soon after, the Turkish performance artist was flitting back and forth under pouring strobes of white light on the steps of Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, performing their work VENUS. We craned our necks to peek between the backs of heads and illuminated screens.

On social media, fragments were viewable at close range: Kunak, in shimmery red stiletto-footed leggings, side-by-side with a bodybuilder; Kunak posing in a surfer stance atop the car with another performer; the artist hanging outside the window of a BMW. It was an enthralling succession of edits; the bodybuilder’s oil-slicked body coruscated in the vehicle’s headlights as the car began to move. Through this score of Instagram reels, one could believe they had stitched together an impression of the piece, but they would be wrong.

“VENUS looks good—I know,” the Berlin-based artist wrote to their followers on Instagram some time after the performance. “…But there’s more to it.” The artist noted a moment many observers—or, better stated, those filming—may have missed: “At one point … I read a text almost no one talks about,” a transgressive “collage of Islamophobic, racist, and xenophobic sentences” used by “public figures.”

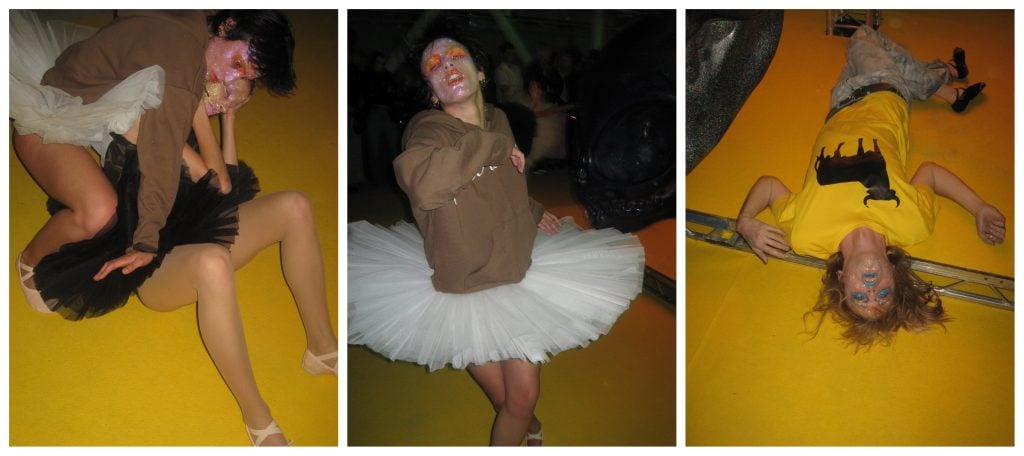

Göksu Kunak’s work VENUS by Jiri Abendt

That part of the work lent a whole other aura to VENUS, which, if you went only by the edits on Instagram, was an intentionally hyberbolic, cliche-loaded series of tableaux, as the artist called it, a soap opera. As the visual elements of the performance waned, Kunak’s political outro went unnoticed by many who hastened to stow their phones away. Was it cut from coverage also because there was “nothing” to film?

Meta’s Instagram has become the place for connecting and succeeding in the art industry, our very own LinkedIn for artists and all the curators who find them and show them, the dealers who represent them, and the collectors who buy them. By now, the art world is well into its DM-era, and it is also growing into its reel-era. But as the UX of the program has evolved, the image-loving platform has tipped its hand in favor of video content. And while this is showing itself to be boom time for performance art, it comes at a cost as our view and collective memory of dynamic pieces are increasingly fragmented by shorts and edits, and the artwork is also beginning to change.

Img Jae Kim YBDG with Dusty, Madison Wada, Nica Roses, Maria Metsalu, Manu Anima, Rhizome, NYC 2024

Performing the Feed

We are in a feedback loop in which social media edifies and dictates taste. In a time of strained attention, where every next post in the feed threatens to be a succession plan for what came before it, content makers (in the case of the art world, artists, the places that host them, and the professionals that orbit them) are looking to land on the grid and stick there. Instagram, an image-forward platform, has suited visual art well since its inception; with the casual network vibes reminiscent of a social potluck, off-hours identity and professionalism merge in a way that suits art industry codes very well; vacation pictures from Hydra can be as on-brand as in-depth reviews about work, checking in online to spaces of the art world can be a measure of your relevance.

There seems to be a link here with the increasing frequency of highly film-able live events, growing ever more popular in museum and gallery programming. Artists, as a result, may feel encouraged to fold in a live aspect to their practice; the audience is keen to check in and show their attendance at it. And in that mix, something is happening to aesthetics.

Performance artists, for whom live moments are at the core of their work, are being pushed to the top of this virtual atmosphere, which is an exciting sea-change. Yet, more and more, their content finds traction if it makes sense to us in under ten seconds; what gets buried and seen is tightly bound up in what fits into the rules of virality. In Contagious, Why Things Catch On, SEO marketing pro Jonah Berger states the recipe for viral content: social currency, triggers, and emotion are among them. In other words, what is highly evocative (even if just formally), what hits on buzzy keywords, and what has strong abilities to speak fluently to a large social group, is marked to succeed. And in a world where time and attention are broken up into piecemeal, art institutions appear to be more inclined than ever to have art activations that follow this recipe of success.

As such, a new scenario has emerged where a certain form or edit of performance art has become synonymous with art events. It is no small wonder that so many rising stars lean on rawness, body candor, and codes of intense intimacy. It is one way to push back at the flattening logic of algorithm and a sense of virtually dictated sepia-toned consumerism. The shape-shifting art collective Young Boy Dancing Group, whose performances have involved candles inserted in their asses or wax dripping on bare chests, let us witness crucial amounts of kinship and trust. Improvisation is like an authenticity test, and the way it is ephemeral and carnal defies machine-generated content. But it doesn’t mean that it escapes the logic of feeds as their duration performances get spliced into the most sensational bits. Seen one way, we are witnessing (and participating in) our own version of what happened in the music industry, where new songs are reduced to the hook as they get picked up by TikTok users.

In the 2024 book Filterworld, author Kyle Chayka discusses a pervasive sense of “ambience” in the culture of the moment. What “thrives in Filterworld,” as he dubs our cultural zeitgeist, “tends to be accessible, replicable, participatory… It can be shared across wide audiences and retain its meaning across different groups who tweak it slightly to their own ends. … This is the culture of presets, established patterns that get repeated again and again. The technology limits us to certain modes of consumption; you can’t stray outside the lines.”

Michele Rizzo, REACHING, 2021. Performance at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, in collaboration with Julia Stoschek Collection. Courtesy the artist; Photo: Frank Sperling

Drawing inside the lines up until recently meant making things on canvas or variants of that. Paintings bloomed as a dominant online form for art—an easy fit to the space of a JPEG. Chayka notes how the format was ideal for the platform, easily able to be recommended, reshared, and, ultimately communicated (and sold) frictionlessly on Instagram. As a result, the Instagram pressure chamber baked a cohort of artists who rose to our attention with what was dubbed “zombie formalism” before “zombie figuration” succeeded it on our feeds. In spite of what I believe were meaningful intentions from painters, each of these styles soon became a gimmick. Chayka writes about the anxiety that underpins all of it, and namely “the fear [that] algorithmically driven art is the obviation of the artist.”

Social media has, at the same time, made a lot of artists a lot of money and brought the art world new levels of attention. But it is worth asking if it is pushing forward the medium. If we look at painting, by and large, its bubble era has led it to hit a stasis, and now, fully capture by the internet and the market, treads water between figuration and abstraction, with few new forms happening. It may be a cautionary tale for performance art, which is increasingly becoming optimized for social media, consciously or subconsciously, as a concept or by accident. As more performances are designed to be visually striking and easily consumable in short video clips, the risk is that the more nuanced, challenging, or less immediately gratifying aspects of the work may be neglected or even sacrificed altogether.

Installation and performance view of performance art by Anna Uddenberg, PREMIUM ECONOMY, Kunsthalle Mannheim, 2023

Courtesy the artist; Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.

Photo: Jens Gerber © Kunsthalle Mannheim / Jens Gerber

Reality Chasers

In the reel era, painting was bound to lose, at least in terms of social media hype (performance art is far, far behind when it comes to art market hype). From what I see on my feed, painting is losing a certain amount of viral clout, especially as compared with ascendant stars of performance art. You don’t quite get “media moments” at a painting opening that you can post about with quite the same frenzy, for one thing. At Art Basel last year, VIPs swirled around with their arms extended, filming Čiurlionis Gym by Augustas Serapinas. This year at Unlimited, Anna Uddenberg’s visually striking Premium Economy took its place as the reel moment of the night.

Many works of performance art that captivate the art world’s attention right now share a similar quality of being all variously themed and styled tableaux vivants. Stay for a long while or a little, post once or a lot, the kernel of the piece is apparent, even though these works are often time-intensive acts of endurance. For viewers, however, it is a different story: they ease the pressure on us in a time of strained attention.

Italian artist Michele Rizzo whose choreography, at first glance, seems to emulate a digital glitch, made waves with his intoxicating piece Higher at Stedelijk in 2022; it only happened for 30 minutes, but it was everywhere in my art world feed, a near-permanent fixture, at least as a snippet of a few seconds. This kind of piece, which sees dancers move through a circuitous pattern of dance moves, is brilliant because it functions as an edit and is fluent in the long form—that mutability is key to its life online. Seen only virtually, though, Rizzo’s practice may seem to be largely about club culture codifications, but when you watch a piece in situ, like I did at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, where Rizzo’s work Reaching was presented, a more interesting aspect emerged—human bodies were set against choreography as algorithm. Over a much longer breadth of time, what becomes apparent is how the dancers beat back against machination, their humanness emerges in their flaws, in their syncopation.

Esben Weile Kjær, I Want to Believe (2023) at 180 Strand on Friday October 6, 2023. Photo: Freja Wewer, courtesy Albion Jeune and the artist.

Artists have taken the phone in hand, literally. Using club culture within a wider bag of cultural references, like his peers Rizzo, the Danish artist Esben Weile Kjær folds rave culture into his practice, where performers dance at the edge of a prescribed kind of chaos. Like Kunak, Weile Kjær has worked the audience in as a participant; the performers film one another and their movements ask to be filmed. People draw out their phones and these pieces seem only finished as a social media spectacle, a rash of videos with many filming arms outstretched. The audience becomes an extension of the artist.

The secondary benefit is that artists have then created high-impact imagery that fluently communicate online, even though it is far from the entire story of the piece. The sensationalist tendencies to get each other to pay attention is a paradoxical gesture, and works that let you stare without shame or watch on loop is a pharmakon for the virtual desire machine.

There may be other ways; performance artist Anne Imhof’s career is an interesting one to consider as an example—and also a foil. The German artist rose alongside social media and worked with and against its changing rapids, dealing with its physics in artistically strategic ways. I think back often to the first performance I saw of hers, in 2014, which was profoundly different from the later works that would bring her worldwide fame. Back in 2014, when she was shortlisted for the Preis der Nationalgalerie, Germany’s answer to the Turner Prize, we were a relatively small audience that had been sat in the room, on the ground, for about two hours as turtles and performers moved at about the same pace; phones were not out and instead a narrative emerged in a way that was tantalizingly languid.

A few years later it was very different; in Venice in 2019, Imhof’s performers were armed with their own cellphones at the German pavilion, filming back at the titillated viewers who pushed into the Giardini to check-in at Faust. By the time I saw her show “Youth” at Stedelijk in 2023, Imhof had removed every in situ performer from that installation. Everyone was gone.

Installation view of Anne Imhof’s “Youth.” Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam co-presented with Hartwig Art Foundation. Photo: Peter Tijhuis

The Edit

Göksu Kunak, like many performance artists, works with an editor to ensure that the narratives they meant to infuse into the work remain present in the documentation. The work becomes a living thing, held by the hands of others who film.

Still, that is only part of a wider story of aesthetic drift. If the edits we all collectively make push performance art towards the logic of a pop hit, with slices of edits working like melodic hooks that become memorable, a new style of work is locked in. When the bracketed edit is what matters, and the nuances of a performance piece are lost when a work is edited down by users to the most salient bits, artists may start thinking about that end point as they are making the work.

Many younger artists may not feel able to afford to tack the way of Imhof, or even of Tino Seghal (Seghal famously denies the filming or documentation of his work, though even that rule seems to have been broken at the Beyeler Foundation’s summer show this spring), and still opt to embrace the spectacle-loving masses on the feeds. Yet, if we follow Chayka’s diagnosis, and if performance art follows the push of the algorithms and is formed and made anew under virtual logic, then it can risk, like painting did, to become equalized and rendered average in the face of the flattened feed, to fade into ambient buzz. While artists may feel like they are in control when they are harnessing the spectacle, a more complex and problematic situation is emerging as performance art, at its core, is being optimized to fit into our viral-loving world.

In the digital distraction, what platform logic favors and what it rejects, what gets left in and what gets edited become decisive factors in what happens in the world of art and aesthetics. So we better stop filming and ask ourselves what is losing out. What didn’t stick? What did not adhere to the math of a performance pop hit? And how will we find it anymore, if we were not there to upload it?

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content