It is rare that I go see an exhibition (or act at all, really) out of spite. Where and how we invest our time says a lot about what we value, so I don’t seek to spend my time visiting or writing about shows that are not successful or of interest to me. When I first heard the title of the Dallas Museum of Art’s exhibition featuring contemporary women artists, He Said/She Said: Contemporary Women Artists Interject, I was shocked at the flippant and thoughtlessness of the title, and was immediately put off from seeing the show.

I imagine whoever came up with the title felt it had a cheeky, playful appeal, but the phrase, which on the surface speaks to a situation in which two people have contradictory claims, is also closely associated with violence and sexual assault; it is often used to undermine or outright dismiss a woman’s experience. In addition to the phrase’s broader connotations, the fact that seven years ago the DMA’s Senior Curator Gavin Delahunty resigned from his position in response to allegations of “inappropriate behavior” even more so calls into question the museum’s naming decision. Though details were never officially released about Delahunty’s behavior, an ArtNews essay published around the same time by artist Natalie Frank alludes to a curator with the nickname “Grabbin” who made unwanted sexual comments and advances during and following a studio visit.

Problematic title aside, the exhibition, which opened in December 2023, stuck in my mind. I was compelled to see how and why the museum would choose to curate an exhibition of women artists that specifically related their work to their male counterparts, rather than allowing them to stand on their own. The title alludes to women artists adding their voice to a larger dialogue (it is worth noting that art history is overwhelmingly male), which is the entry point for the show.

The introductory text notes that the women artists in the exhibition “call into question the myth of the sole male genius and create space for new, more inclusive narratives.” Works in the first gallery are by women who make direct references to specific artworks by male artists. This includes Deborah Kass’ Making Men #3, which incorporates a long ruler used to scrape paint in a circular motion, à la Jasper Johns’ Device. The wall text also points out Kass’ other references to forms in Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic, 108 and figures painted in the style of David Salle. Additionally, this gallery includes works by Sarah Charlesworth and Carolee Schneeman that speak to Jackson Pollock’s iconic drip painting style.

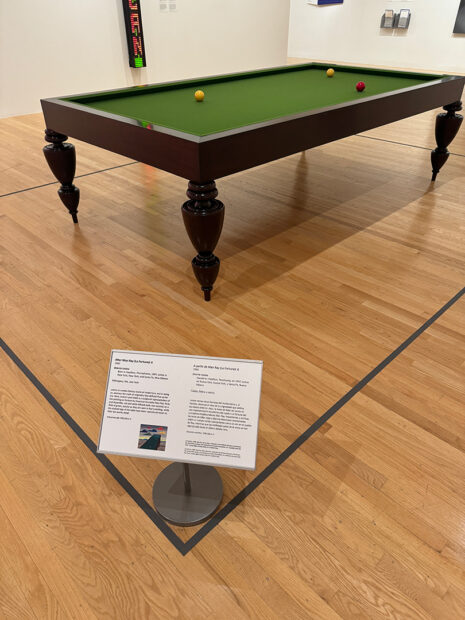

Stepping down into a larger gallery space the show gets a bit messy, mostly because the room is big and open, and as a visitor it is hard to determine where to go next and which pieces are associated with which wall texts. Sherrie Levine’s After Man Ray (La Fortune): 6 seems like it belongs in the first gallery as it is a direct reference to a painting by Man Ray that is printed on Levine’s label. But what about Rachel Hecker’s Parboiled and Joyce Pensato’s Felix, which are installed on the wall behind Levine’s sculpture? Is there a direct reference here to the work of male artists? If not, what are Hecker and Pensato interjecting? Isn’t all new art an interjection of sorts?

Other walls of this gallery showcase works by Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Lorna Simpson, and more. Heavy hitters? Yes. Important women artists? One hundred percent. Was I excited to see their work? Unquestionably. But, the “why” of it all — why these women, why these works in conversation with each other, why works from this specific era — still wasn’t coming together beyond this being a show featuring women artists. Two section text panels in this gallery were titled Women and Appropriation and “Black Female Subjectivity.” The appropriation panel discusses how Postmodernism “opened the art world to women,” and that women artists using appropriation were questioning “the validity of male genius and critiques of the images of women as objects of sexual desire…” Both of these strange statements, namely because they immediately brought to mind pre-postmodern women artists who were wildly productive and also successful in their time, such as Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Cassatt, Suzanna Valadon, and so many others.

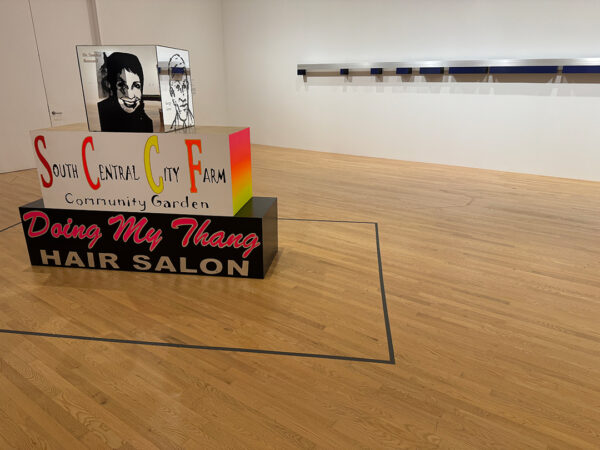

The “Black Female Subjectivity” panel is a deeper dive into appropriation, specifically considering how Black women artists have appropriated imagery by white male artists. With the wall label for Simpson’s Blue Turned Temporal, I couldn’t help but feel that her work was being put too much in the context (out of sheer visual similarity) of Frederic Edwin Church’s The Icebergs, a painting which she is not directly referencing but happens to be in the museum’s collection. Similarly, I found myself questioning the label on Lauren Halsey’s South Central City Farm / Doing My Thang, which speaks about her work in reference to the minimalist cubes and rectangles of Donald Judd. It feels like more is lost than gained with this comparison; as a museum visitor, I’d much rather know more about Halsey’s community work and inspiration drawn from Parliament Funkadelic.

The back gallery had one section titled Friendship and Collaboration, as if it was necessary to point out that sometimes men and women are friends and collaborate. While artist friend relationships are interesting and can shed light on the ways they influence each other, this section felt disjointed when considered after the front gallery. The section includes a pairing of Calida Rawles’ In His Image, a portrait of artist Diedrick Brackens, alongside a textile piece by Brackens. The similarly arranged adjacent wall features a work by Toyin Ojih Odutola depicting Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in front of Sigmar Polke’s Clouds (Wolken), as well as works by Yiadom-Boakye and Polke. But also included in this section are several decorative arts pieces. I appreciate the range that highlights the institution’s varied collection, but it contributes to the haphazardness of the display.

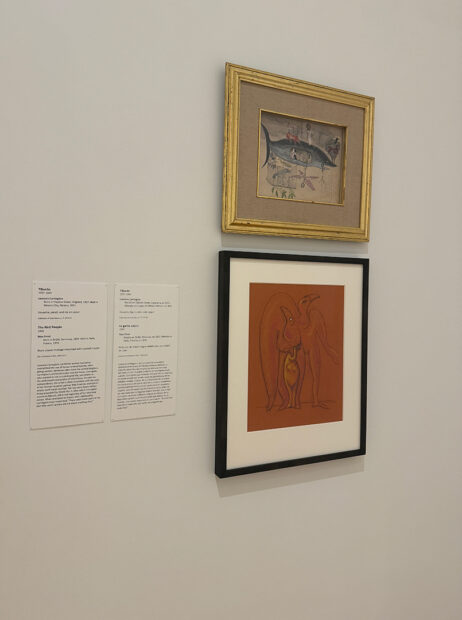

The other section of the back gallery is titled Women in Surrealism and includes works by Myrna Báez González, Julie Curtiss, Ivy Haldeman, Emily Mae Smith, and Leonora Carrington. It was perhaps ironic that the label for Carrington’s work pointed out that “despite her independence, the artist is often associated with the work of her former romantic partner Max Ernst,” whose work is then shown alongside hers.

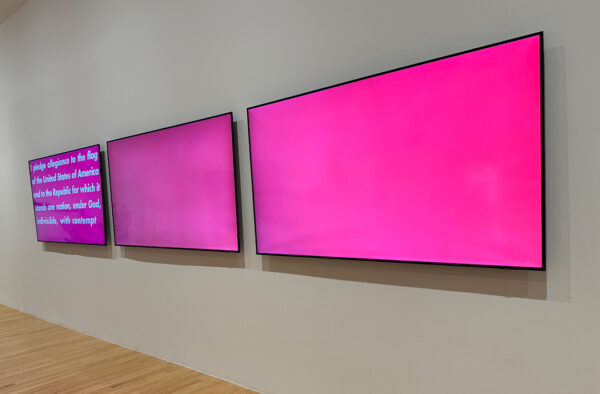

Barbara Kruger, “Pledge, Will, Vow,” 1988/2020, three-channel video installation of three LED flatscreen monitors, sound, 5:35 minutes.

Reflecting on the exhibition over the last few weeks, I’ve had a quote from The Office stuck in my head. Michael Scott is emceeing a typically insensitive “teaching moment” while dressed in a fat suit. Jim says, “You’re always saying there’s something wrong with society, but maybe there’s something wrong with you.” Michael retorts, “If it’s me, then society made me that way.” On this note, I feel the DMA is not totally to blame for this exhibition’s failings. Museums and art institutions are a part of the fabric of the art world and despite the changes they are striving to make, because their collections are shaped by the systemic and systematic exclusion of women they can only reflect the art canon as it is.

Zooming out even more, these institutions and the art world at large is merely a reflection of society. For centuries we have seen how society has valued and treated women as lesser than men. It was only in 1900 that every state had legislation allowing married women the right to keep their wages and own property in their name. Another twenty years later women were granted the right to vote. It took until 1974 for women to be allowed to apply for a credit card in their own name. And even with decades of progress, today we see women’s rights slipping away. How can we expect institutions that emerge from a society that views women as less important or less deserving, to provide justice for women in a field such as visual art?

But then I also think of other successful exhibitions platforming women artists such as Women Painting Women at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas Women: A New History of Abstract Art at the San Antonio Museum of Art, and Commanding Space: Women Sculptors of Texas at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Not to mention the books that have been actively attempting to revise the canon through real scholarship, like Katy Hessel’s The Story of Art Without Men and Mary Gabriel’s 9th Street Women.

He Said/She Said displays significant works by women artists, some of which I had never seen in person before. However, I wanted it to do better. I wanted more women artists; I wanted a deeper history of women artists; I wanted more work by each of the women artists on view. Yes, some of the artists in the show were directly referencing the work of male artists and it was good to see those pieces side-by-side, but the rest of the exhibition felt loosely strung together. Both the women artists on view, who are only now getting the recognition they have deserved for years, and visitors to the exhibition deserve better.