Recently, the Langmatt Museum in Switzerland sold three paintings by Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne to save itself from being permanently shut down. The announcement of the auction at Christie’s reopened a debate (or perhaps it has never been closed in the first place) in the art world that combines solemn concepts like protecting artistic heritage, saving the jobs of perhaps hundreds of people, guaranteeing the survival of an art center, allowing museums to sell artworks to expand or renew their collections and the role of states in this whole affair.

“It was the end of the line,” Markus Stegmann, the director of the Langmatt Museum in Baden, Switzerland, tells this newspaper. His museum contains one of the most important Impressionist art collections in Europe. He goes on to explain that “the foundation that manages the museum no longer had capital. We needed 40 million Swiss francs [about $47 million] and after years of trying to find another solution we came up with this one: selling three paintings from a collection of about 50.″ In the end, they got even more, €48 million (or $52.6 million) for the three canvases sold at auction at Christie’s last September. The museum was saved.

But that is only the end of this story.

Chapter 1: The Goldsmith family’s painting

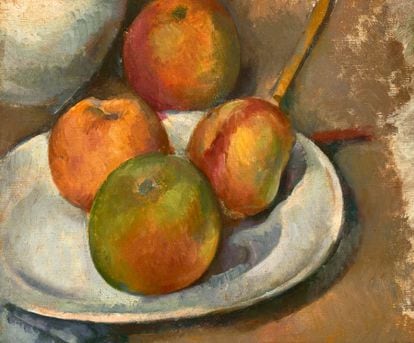

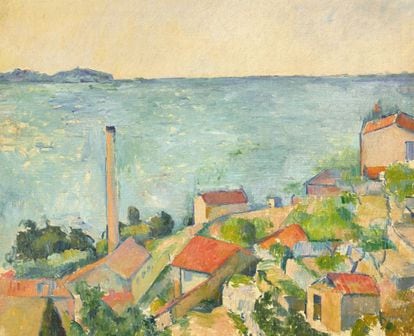

The Langmatt Museum chose to sell Quatre pommes et un couteau, La mer à l’Estaque and Fruits et pot de gingembre, the painting for which they had the highest hopes; those hopes were confirmed when Christie’s charged an estimated price of between $35 and $55 million (it ultimately sold for almost $39 million), fetching the highest price of the three pieces.

In 1933, Sidney and Jenny Brown, the couple who founded the Langmatt, bought Fruits et pot de gingembre in Lucerne, Switzerland, from the German-Jewish Goldsmith family of art dealers for 57,750 Swiss francs. Stegmann considers that sum to be within the market price at the time, but he says that he does not know what percentage the original owners took. So much for what appears to be a normal commercial transaction between two art galleries.

But once the Cézanne painting was in Christie’s possession, the auction house discovered that the Goldsmith family had not escaped the initial Nazi persecution, and that Jacob, the work’s first owner, had been coerced into disposing of part of his collection. “In January 2022, we began an investigation with specialists outside the museum on 13 works that had been acquired between 1933 and 1941, the year of Sidney Brown’s death,” explains the Langmatt’s director. “In the case of this painting, we did not find clear evidence until the auction was announced.”

For that reason, Stegmann says, they contacted the Goldsmiths’ current heirs immediately after securing this evidence. Mara Wantuch-Thole, one of the lawyers representing the Jewish art dealer’s grandson, explained to The New York Times that he was unaware that his grandfather had owned the Cézanne painting until the museum foundation contacted him. “We have reached an agreement,” the lawyer told the Times. The director of the Langmatt declined to share any further details about the agreement but calls it “a fair and equitable solution.” He added that “it’s confidential.”

Chapter 2: Selling three paintings to pay the bills

The sale of Cézanne’s paintings in Europe opened a debate about an issue that is more common in countries like the United States, where the management of major art galleries is guaranteed by private capital and philanthropy (essentially another way of saying private ownership) and there’s little government involvement; that is, they don’t receive much public funding.

The Swiss International Council of Museums (ICOM) representative Tobia Bezzola was the first to warn of the danger that, as he put it, this “scandalous and short-sighted” art sale posed. He went on to allege that it violated the organization’s code of ethics. “Bequests and donations come to museums because people believe they will be safe,” Bezzola told the Swiss press, demanding that the auction not take place. “All of Switzerland’s important collections come from private donations and bequests; it sends a terrible signal.”

“These criticisms are based on a code that needs to be revised and adapted to our times,” the Langmatt director says bluntly. “It does not foresee an existential emergency in a museum. Forty years ago, it was another time,” Stegmann emphasizes. He adds that in Europe, “museums receive less and less public money.”

Several similar recent cases in the United States come to mind. During the pandemic and the first months after the strictest lockdown, the Brooklyn Museum in New York put 12 paintings up for auction at Christie’s, including works by important names like Lucas Cranach the Elder and Gustave Courbet. They did so to try to raise $40 million to cushion the economic crisis resulting from the plummeting number of visitors due to the collapse of tourism. This example prompted the Association of American Museum Directors (AAMD) to approve a measure “not to penalize sales that serve to pay expenses associated with the care of [museum] collections” through April 2022.

In other words, new red lines were established to allow some commercial transactions. “No precedent of any kind was established because this decision ended in 2022,″ the AAMD tells this newspaper. “In fact, only a few museums sold work to address financial needs.” How many? “We don’t have that information,” they say.

Chapter 3: “Museums are not supermarkets”

In September, when the auctioneer at Christie’s banged the gavel, those at the Langmatt breathed a sigh of relief. It was the most extreme solution they could find. Its director emphasizes that “this does not mean that museums have to sell their objects. That would be extremely dangerous; museums are not supermarkets!”

Stegmann denies that his decision sets a precedent in Europe. “It is absolutely unique and should be regarded as such,” he says. “The Langmatt’s existence was threatened. This museum was able to rescue itself without destroying its collection and identity.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content