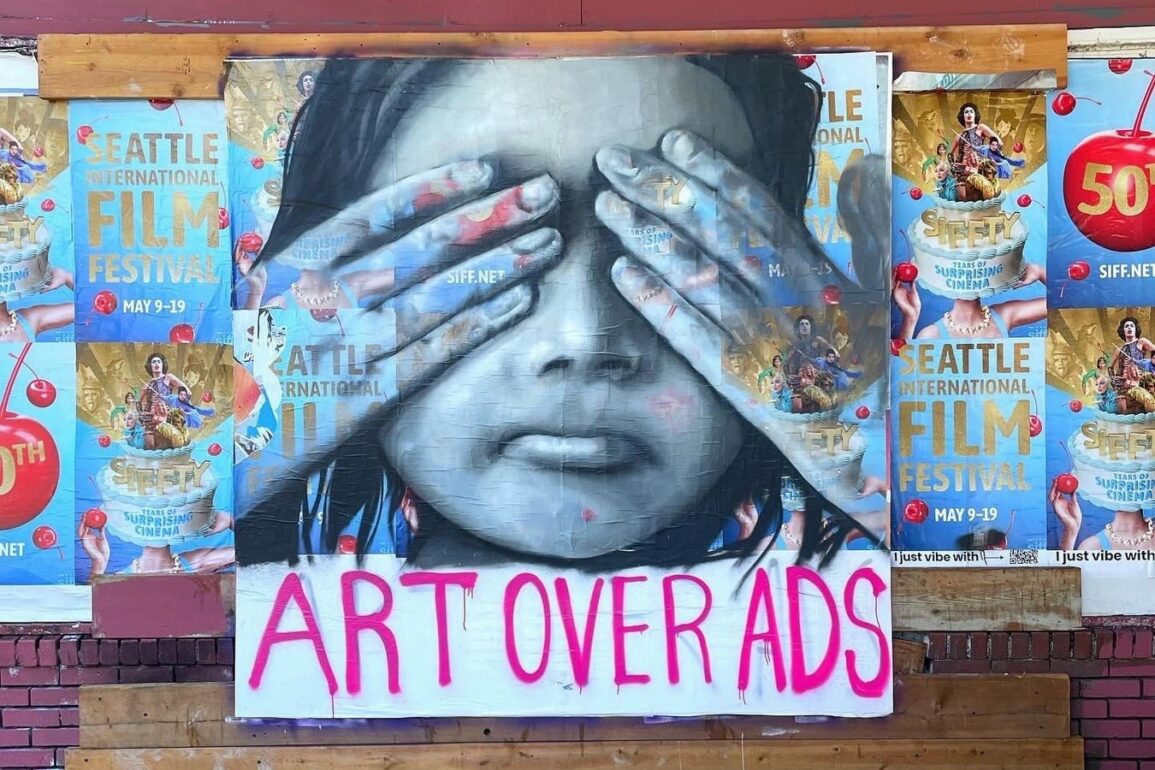

On an early summer evening last week, a group of 30 artists gathered in downtown Seattle to create public art on top of advertisements. This community-organized movement served as a social commentary on the tension and asymmetrical dynamics between art and advertising in public spaces.

Artist Brady Black brought the group together after observing the use of public space throughout his career as a muralist. “It astounds me how we allow advertisements to do pretty much whatever they want, but any public art is under massive scrutiny,” he shared.

Because the eyes – and thus perspectives – of a community are influenced by what they see around them, there are real implications to having this exposure available to the highest bidder. This decides who gets to make their mark on our public spaces and who gets left out, highlighting the economic and social inequities at play.

Art is gatekept from all angles. Art that makes it into museums and galleries is filtered in ways that have historically kept diverse representation to a minimum – with artists shown in US museums being 85% white and 87% male – as well as only reaching the subset of the population that frequents those spaces. Public art projects are carefully curated, edited and compromised by the organizations that have sponsored the projects, often resulting in diluted messages. And unsanctioned street art may be quickly covered, erased or even penalized.

Art Over Ads artist

“It’s so hard to get art up in the city,” Black reflected. “You have to have a permit, have a listening session. The community association has to see your thing and make sure that your colors match. If anyone’s offended by any elements of the design, you have to change the whole thing, or they could even shut the entire project down.”

In contrast, the limits on public advertisements are mainly financial, with a forecasted $9.34 billion to be spent in 2024 in the US alone.

Greg Morrison, the co-founder of MXML Creative, explained: “Typically, the challenge a brand faces when they want to create out-of-home (OOH) advertising is not limited by regulations specific to that one city or state, but instead what is allowable by the company that controls the billboard, bus shelter, park bench, etc.”

Laura Mai, Marketing Director at Grit Blueprint & freelance consultant, recounted her time helping clients advertise in public spaces. “Regulations about ads in public spaces are mostly around consumer goods and political ads,” she shared. “You can’t make false claims in consumer goods – they must accurately represent prices, testimonials and the product itself – but technically you can in political ads as long as you state who is paying for the ad.”

“It astounds me how we allow advertisements to do pretty much whatever they want, but any public art is under massive scrutiny,” Black reflected. “Wouldn’t it be better if the advertisors had to beg and plead for their right to exist and be accepted in our public spaces?”

The tension between public art and advertisements is not limited to the US. Aislan Douglas, a multi-disciplinary artist from Paraíba, Brazil, has observed this dynamic as well. “Economic inequality places corporate advertisements in visual dominance due to their virtually unlimited budgets, making them ubiquitous. In contrast, public art relies on limited public funds that rarely cover the total costs of projects,” he shared. “This economic imbalance contributes to the predominance of commercial messages over community artistic expressions.”

The imbalance of advertisements over public art has a tangible impact on communities.

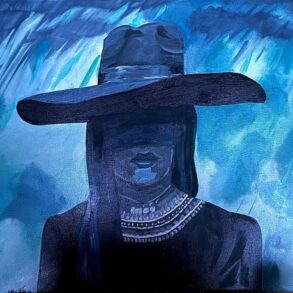

London Shoreditch street art

“I think relentless advertising in public spaces is harmful to people psychologically, financially, and physically,” shared Andre Decolife, a Brazilian street artist living and painting in London. “It offers no respite to their eyes, and deprives them of their own ideas or thoughts as they are inundated with storms of products they’re supposed to have.”

“I’m the one that’s being sold. My attention is being sold,” Black exclaimed. “Look at all the billboards and signs and sides of buses – they have no artistic value at all. Art cares for you. Even if it’s trying to challenge you, it actually cares for you. All the advertisements are just selling you.”

Douglas agreed. “While advertisements aim to capture the public’s attention unilaterally, public art seeks to engage the community, providing a platform for reflection and dialogue.”

Black recounted how he first started doing street art. “I was having a show at a gallery and a guy said to me, ‘the people who need to see this won’t see it, because they won’t go to a gallery.’” Then recently, when one of his pieces was covered in advertisements, he re-created the piece on top with the words “Art over ads.” That led to this latest movement of artists pushing back on the advertisements that surround them.

Art Over Ads project in Seattle

Black intentionally kept the Art Over Ads project uncurated, as a contrast to the rigorous applications that go into gallery exhibits and residencies. He wanted to bring together artists who hadn’t ventured into public art before. “Public spaces are for the public, but they don’t feel that way anymore. This project is busting through all the gatekeeping, and doing it together. This is a noncompetitive space. If you show up, you’re part of the team.”

Douglas sees hope for a world where we shift the scales between advertisements to art. “By balancing the presence of corporate advertisements with community artistic expressions, it is possible to create urban spaces that reflect the diversity and cultural richness of our communities.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content