As a young art student at Melbourne’s RMIT at the end of the 1950s, Lesley Dumbrell was among a cohort of mostly women, contemplating a profession that was dominated by men. Even so, she was shocked when the head of the painting department blithely told her that he was happy to have women in his class “because no doubt they’ll get married, and if they marry well they will become very good collectors of art”.

“That was enough to get me going,” she recalls. “I thought: right, I’ll show you guys.”

That comment kickstarted a career that is now in its seventh decade, and which hit a high-water mark this week with the opening of a major solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) – her first survey in a state art museum, arriving at the age of 82.

Dumbrell is not finished, either: recent forays into sculpture have resulted in an ambitious laser-cut metal work created specially for the new exhibition, and ahead of the opening on Friday her brain was sparking with fresh ideas. “Already, I can see there’s a thread here from what I’ve been doing that I could take further,” she said.

Being “endlessly curious” is fundamental to Dumbrell’s endurance, says curator Anne Ryan. Curiosity is also what led Dumbrell to abstract art – a genre that was “forbidden” when she was at art school: “And once you shut a door like that, you know, I’m the one that will always say, ‘Well, I want to find out about it!’”

She pursued extracurricular lines of inquiry, studying Piet Mondrian reproductions and reading Kandinsky’s treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which argued for the transcendent power of abstract art. Something clicked.

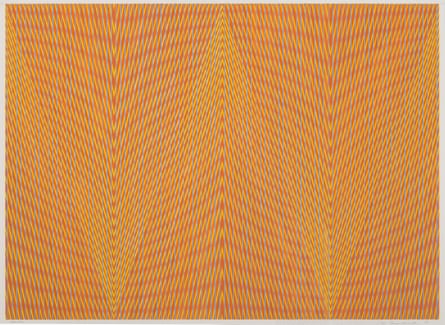

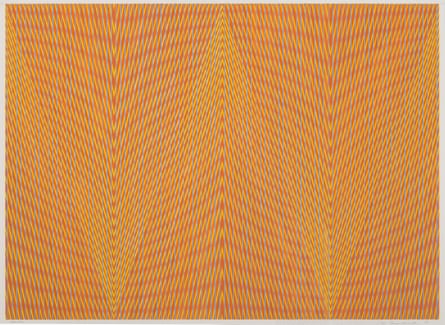

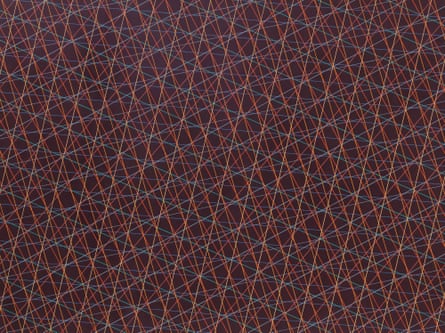

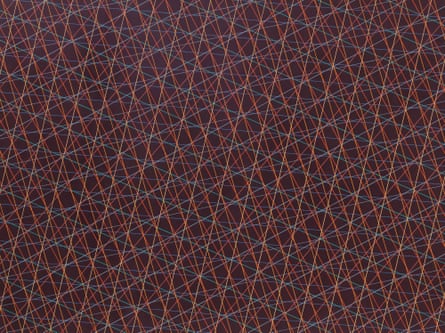

Her second big revelation came while teaching art at the Prahran College of Advanced Education in the 1960s, when she discovered the optical paintings of Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely, among others. “I found [them] absolutely intriguing,” Dumbrell says. She started to experiment, using precise geometric systems developed via trial and error on grid paper with pencil (many of which are on display in the AGNSW exhibition).

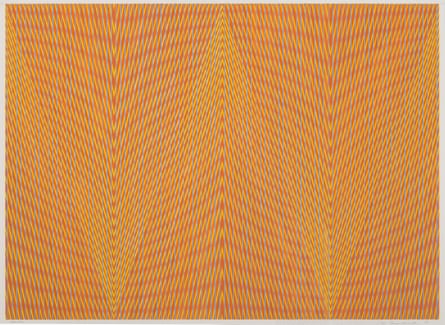

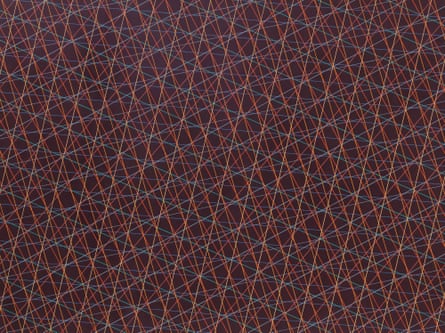

Walking through the loosely chronological exhibition, you can follow that thread of curiosity, from her hard-edged geometric abstraction in the late 60s to her optical paintings in the 70s, then the explosion of colour and form in the 80s as her style flourished into looser arrangements of seemingly organic forms.

The constant throughline is nature. “I just love the landscape,” Dumbrell says. “I love the whole wind, the sun, the shadows.” Her paintings often sought to capture her sensory experiences: the sensation of a breeze, the effect of rippling water, the colours of autumn, the texture of light through eucalyptus branches. The exhibition’s title, Thrum, tilts at the vibratory, energetic quality of these works.

Many of the paintings are huge. “I was surprised at how big some of them are. I forgot,” Dumbrell admits as we walk through the exhibition before the opening. Her ambition paid off: a triptych of gargantuan canvases titled February, made in 1976 when Dumbrell was just 34, was acquired by the National Gallery of Australia – an auspicious sign for a young artist.

She smiles: “I was young and bold, and I wanted to do something big – so I did it.”

Ryan sees both fearlessness and focus in Dumbrell’s approach. “She’s always done exactly what she’s wanted to do artistically; she’s never been fearful or asked for permission … She was never trying to meet a market.”

As she followed an individual path artistically, Dumbrell was thinking collectively, spurred by a growing political consciousness and her involvement with the feminist Women’s Art Movement (WAM). A 1975 visit to Melbourne by the US critic and activist Lucy Lippard was a turning point: Dumbrell’s friend, the gallery director Kiffy Rubbo, asked her to drive Lippard around Melbourne as she sought out work by local female artists.

The two had a frank discussion. “She said, ‘Don’t you women get together? Why aren’t you visiting each other’s studios?’” Dumbrell recounts. “I said, ‘It’s just not something that we do’, and she said, ‘Well, you’re stupid. This is a business. Get on with it. You girls have got some power – you’ve gotta put it together.’”

Lippard’s visit sparked something in her: the following year she and Rubbo established the Women’s Art Register, a record of living female artists that became an invaluable archive and remains active almost 50 years later. In 1981, Dumbrell joined the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, where she advocated for redressing the gender imbalance within that board and in the industry more broadly.

In 1989, Dumbrell reconnected with her first husband – after an intermission of almost two decades – and the two moved to Bangkok, where she remains predominantly based, though the two have a home in Victoria’s Strathbogie Ranges.

The move to Thailand resulted in what Ryan describes as a “creative drift”, as Dumbrell adjusted to a new environment and way of life. In the exhibition, her return to form is represented via a series of large red and yellow canvases in which she reignited her love affair with colour, taking Bangkok’s palette as inspiration. Elsewhere on the walls, rhizomatic patterns reflect a breakthrough in the 2010s, when she pushed the boundaries of her previous work with grids.

Looking back at her practice across the exhibition’s four rooms and 90-plus works, Dumbrell says she feels “overwhelmed”.

“It’s like all my children are being herded together in a room, and they’re all going to talk to each other,” she says.

Despite her advocacy for female artists – or perhaps because of it – she says she never expected to receive this level of recognition. “I didn’t even know it would be possible,” she says.

“The women just had to fight for their place more than the men – always – and just hope that [recognition] came along; shut up and get on with it and see what happens – which is what I did.” She pauses, and looks briefly amazed. “And here I am.”

-

Lesley Dumbrell: Thrum is on at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until 13 October.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content