In this article:

In 2017, when Patrick Nolan joined Opera Queensland (OQ) as Artistic Director, after five years leading the pioneering physical theatre company Legs On The Wall, part of his brief was to shake things up.

Little did anyone know that within his first two years at OQ, he would take the company into completely uncharted territory, and enter into what was then seen as a risky partnership with contemporary circus arts company Circa to produce the companies’ first ever opera/circus arts collaboration.

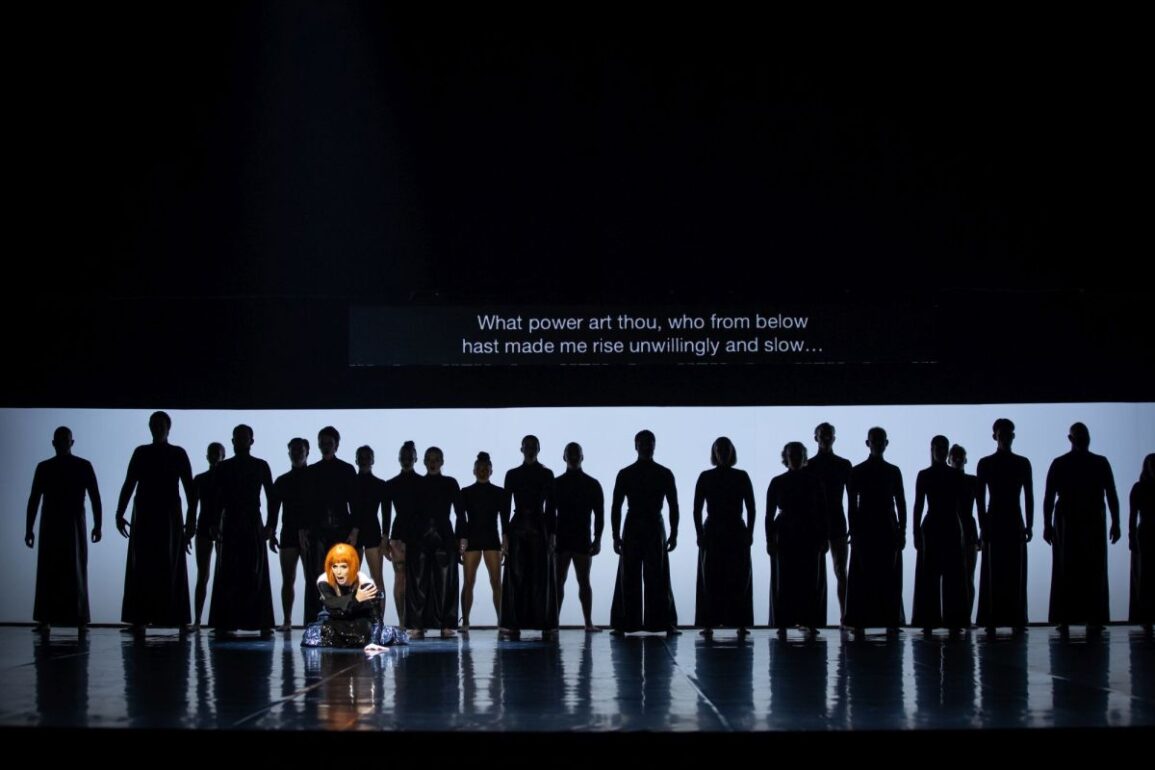

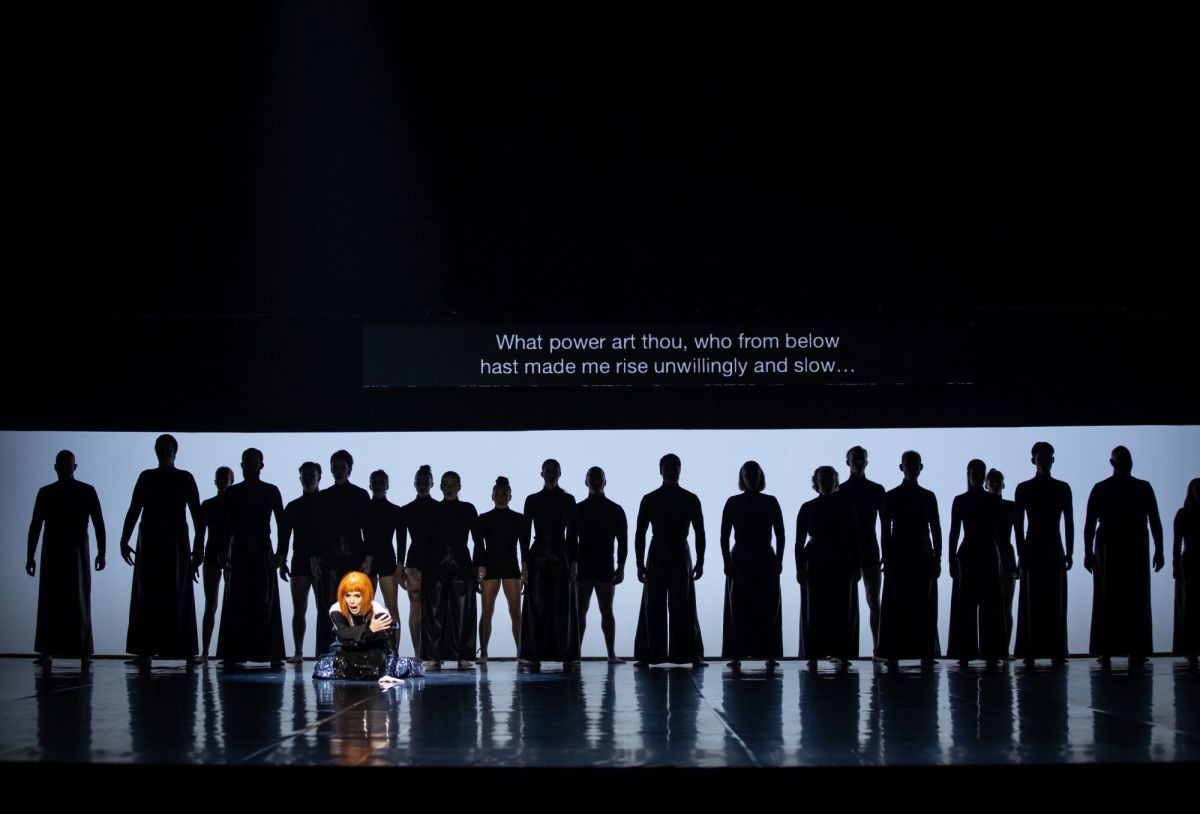

The resulting work, Orpheus and Eurydice, was directed by Circa’s Artistic Director Yaron Lifschitz, and proved an unexpected runaway success, setting its Queensland audiences on fire before dazzling Sydney crowds earlier this year when it was presented by Opera Australia at Sydney Opera House to great acclaim.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, and in an art form that is arguably a million miles away from opera, Spare Parts Puppet Theatre is currently basking in the success of its own novel cross art form production, with its first ever “puppet musical” recently returning from a successful national tour.

The landmark Spare Parts production, The One Who Planted Trees, was written by theatre makers Nick Pages-Oliver and Amberly Cull, with songs and musical arrangements by composers Melanie Robinson and Carmel Dean.

After premiering in 2021, where it drew standing ovations from its audiences, the production won the 2022 PAWA (Performing Arts Western Australia Award) for Most Outstanding New Work.

Read: Puppet theatre knows no bounds

But the big question is whether these recent cross art form success stories are rare anomalies in the wider picture of equally bold collaborations that have failed to make strong impacts, or that have failed to get off the ground at all because their stakeholders were too nervous to back them in the first place.

It turns out that there are a number of specific strategies underpinning these two cross art form projects that have allowed each partner to minimise their risk of failure, and have instead brought two different audience demographics together for increased engagement and wider reach.

So, how exactly did these two companies do this? Read on for some of their directors’ top tips.

Strategy 1: Know thyself and thy partner

According to Circa’s Artistic Director Yaron Lifschitz, successful cross art form projects rely on two main factors: an appetite for risk and a capacity to trust.

As Lifshitz tells ArtsHub, ‘One of the defining things about these [cross art form] collaborations is that you have to give away a lot of your safety nets because you are doing something with people outside your core team.

‘So, when there’s already a sense of trust between the collaborators, that’s good,’ he says.

Opera Queensland Artistic Director Patrick Nolan agrees that a trusting professional relationship with cross art form partners is vital. In fact, his decision to invite Circa’s Artistic Director to work with his company in 2019 was made far easier because of the pair’s established bond.

‘I’ve known Yaron since we did the Directors’ course at NIDA together,’ Nolan says. ‘And I’ve watched him transform what was formerly Rock n’ Roll Circus into Circa Contemporary Circus – now one of the world’s leading contemporary circus companies.

‘So, when I arrived at OQ, I was excited about seeing how he would respond to directing an opera. It was just a matter of finding a work that would suit his sensibility and to allow his acrobats to shine alongside the singers.’

Opera Queensland and Circa have now undertaken two successful collaborations – Orpheus and Eurydice (2019) and, more recently, Dido and Aeneas (2024), both of which have relied on Lifschitz’s multifaceted abilities as a director to interpret opera’s nuances while bringing the energies of circus to the opera stage.

‘Yaron’s sensitive direction of both productions has been another crucial element in their success,’ Nolan adds.

Strategy 2: Think strategically about what each company will gain

Another good way to ensure all parties in cross art form collaborations reap sufficient rewards is to acknowledge from the start that the benefits each partner is likely to receive will almost certainly be very different (and that’s OK!).

In Opera Queensland and Circa’s case, you’ve got one artistic partner whose genre is steeped in history, and whose audience is rather posh. Yet the other art form is more populist and fun, and has far younger fans.

Thus, what their partnership has allowed them to do, is address the gaps that each has in their own audience reach in fairly equal measure.

As Lifschitz explains, ‘You may say that Circa suffers from a bit of an image problem at the posh end of the performing arts.

‘So what these Opera Queensland collaborations have done is to help us shift our image, so we are less distant from that “truffle” end of the arts,’ he continues.

‘And while these co-productions may not have converted huge numbers of opera audiences to our regular circus shows, they have brought a few opera fans into our circle. And these new audience members are so important to the future of our company in terms of helping us expand our networks and attract new financial support.’

Read: The power of creative collaboration

Conversely, on the Opera Queensland side of the equation, the collaborations have helped OQ improve in an entirely different (one may say opposite) area – allowing the company to attract record numbers of younger audiences, which they would not normally be able to do.

‘It was exciting to see how young audiences embraced Orpheus and Eurydice,’ says Nolan.

‘There were significantly higher numbers of younger people in those audiences than usual.’

So, what is the moral of this story? Answer: if you can identify the areas where your company is falling down and seek partners to lift you up in those weak areas, while you use your own company’s strengths to plug your partner’s weak spots, your cross-arts collaboration is likely to be a mutually beneficial match made in heaven.

Strategy 3: Harness audiences’ appetite for delight (especially right now)

The final factor that all three directors recognised as being part of their cross art form success stories is linked to the current zeitgeist, and is perhaps a harbinger of where performing arts audiences are heading.

For Philip Mitchell, Artistic Director at Spare Parts Puppet Theatre, the contemporary defining mood is one that’s pulling audiences towards highly energised and uplifting arts experiences.

‘I feel there is a move away from passive consumption of theatre towards art forms like circus and musicals and puppetry,’ he explains.

‘I think this is because they elicit strong emotional responses and transport you to somewhere magical. And in a post-COVID world, that’s what audiences are looking for.’

He adds that in developing Spare Parts’ first musical theatre cross art form show, The One Who Planted Trees, he realised audiences felt elevated by the combined energies of the puppetry and musical theatre genres, even though the subject matter within the work is no laughing matter.

‘The One Who Planted Trees is a puppet show that uses music as its language, and I think in doing that we have framed a potentially confronting subject – of climate change and environmental collapse – in a very hopeful way.

‘Our audiences leave the theatre with a sense of hope and joy, because it is essentially a very joyful, delightful show.’

Similarly, both Opera Queensland’s and Circa’s directors noticed the combustible energies generated by opera singers and circus artists working together, and harnessed those powers to great effect.

As Nolan explains, ‘On the face of it, opera singers and acrobats appear to be entirely different kinds of artists, but the physicality involved in both art forms is remarkably similar.

‘So, the artists fed off the energies of each other onstage, because they could recognise the level of physical virtuosity involved in each other’s processes. Audiences were drawn to that energy, too.’

Read: The performing arts company breaking every convention in the book

Nolan says the audiences’ connection to these collaborative energies was especially noticeable during the premiere season of Orpheus and Eurydice.

‘One thing I love sharing about that first Orpheus and Eurydice season is that, by the final performance, when there were no tickets left, a group of people who missed out were so desperate to see it they bought seats in the Crying Room, which is a windowed-off space.

‘It seems extraordinary that people were willing to watch the show from those seats, but that’s how excited people were about the show. And I think that [excitement] has a lot to do with the way we combined the two art forms, both of which take audiences beyond the spoken word and beyond the rational. It’s a combination that creates a truly thrilling experience.’

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content