An Artist Flowering in Her Nineties

For more than two decades, Isabella Ducrot, an artist who was born in Naples in 1931, has lived in an apartment on the top floor of the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, in the center of Rome. When I knocked on her door for the first time, this past spring, she greeted me with an emphatic pronouncement in English: “I must tell you immediately that I have never been so happy in my life!”

It was a Tuesday evening in April, and I’d landed in Rome just a few hours earlier. Originally, Ducrot and I had arranged to meet for lunch the next day, but when she learned of my schedule she invited me to come over sooner, for a drink and a light dinner, noting in an e-mail that she “would be enchanted” to see me immediately. She opened the door to the apartment—where she lived with Vittorio (Vicky) Ducrot, her husband of fifty-eight years, until his death, in 2022—and I entered a spacious hallway densely hung with dark, dramatic Baroque paintings. Light shone on them from French doors that led to an expansive terrace. A side table held a vase of roses that were hovering on the edge between bloom and decay. Ducrot, who is tall and upright, grasped my hand more firmly than I would have expected, saying, “Please believe what I tell you. I adored my husband, and I am half a person now that he is not with me. But I am happy—happy.”

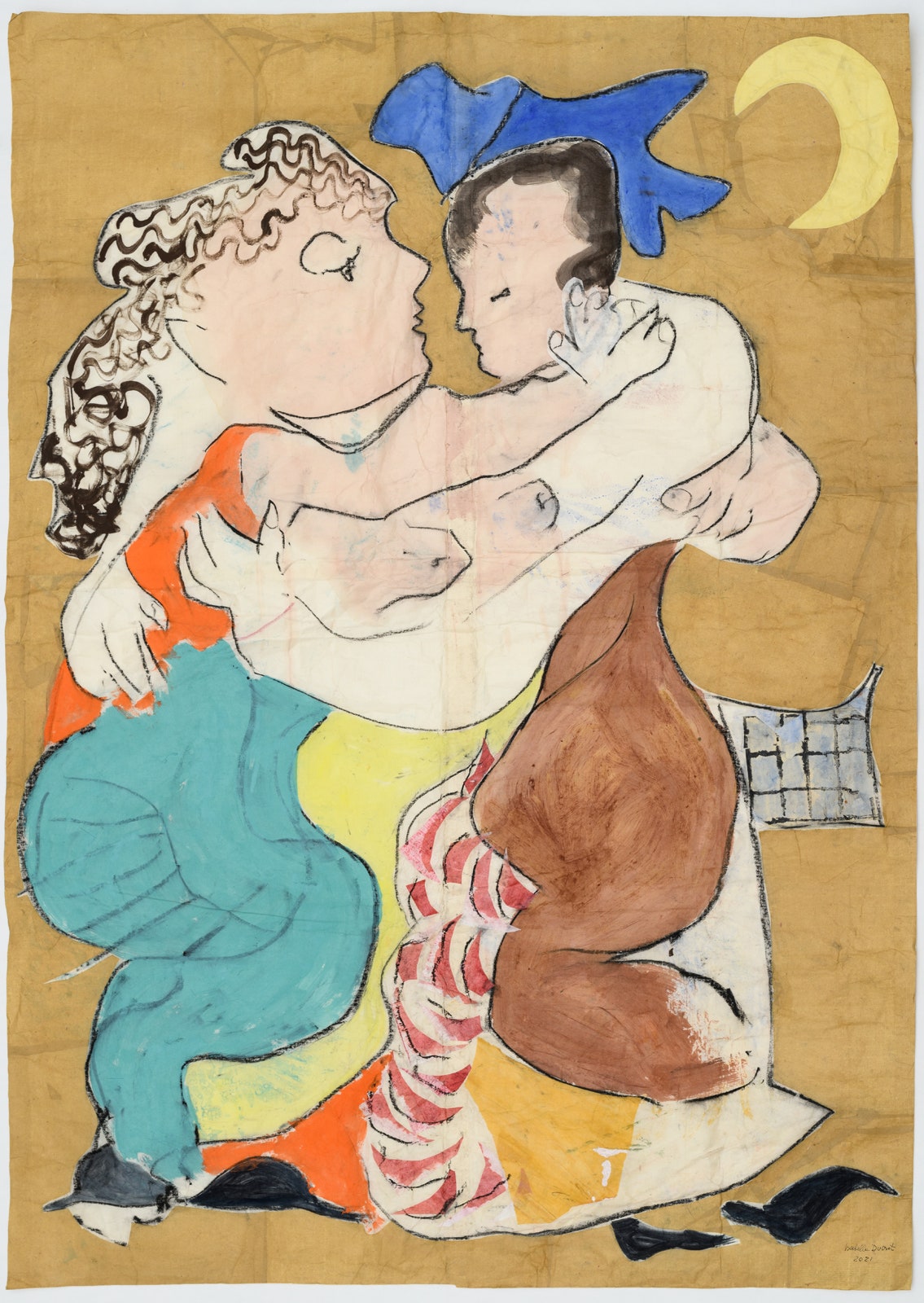

Only in the past five years has Ducrot, who turned ninety-three in June, become internationally recognized for her art, which she didn’t even begin making until she was in her fifties. When creating her works, she stands and uses a brush sometimes attached to a stick, sweeping loose arcs of ink or paint onto paper or fabric. She often later incorporates scraps of other papers or textiles. Her painted collages usually depict ecstatic figures and stylized landscapes; arrays of ovals or checkered patterns are a recurring feature. Typically made in series, her works are light, energetic, and uninhibitedly beautiful.

Ducrot’s œuvre has been admired in Italy for three decades: in 1993, a tapestry was included in the Venice Biennale, and in 2008 and 2014 she had solo shows at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, in Rome. But it wasn’t until 2019 that she was championed in earnest outside the country, when Gisela Capitain, a gallerist in Cologne, Germany, mounted a solo show of Ducrot’s work which featured iterative images of flowers in vases, along with several pieces from a series, “Bella Terra,” each of them depicting a tree and a flowing river. It was as if Ducrot, in her ripe ebullience, had leapt directly into a late-Matisse phase—full of color and shorn of fuss.

This summer, the Consortium Museum, in Dijon, France, is hosting Ducrot’s first international solo museum show, heralding her, counterintuitively, as “a young artist with a young career.” The exhibition includes eleven paintings, on paper, from a series that Ducrot calls “Tendernesses”; they show two figures exuberantly entangled amid a patchwork of patterned blocks. Secured to the gallery walls with pins, the paintings—like the blissful people depicted within them—seem to float unsupported.

Since Ducrot’s husband died, she has shared her apartment with her housekeeper and two cats. Apart from a daily excursion to her studio, on the palazzo’s ground floor, she only occasionally leaves home—a sharp contrast to her earlier life, which was uncommonly adventurous. Vicky Ducrot was the prosperous founder of a luxury-travel company, Viaggi dell’Elefante, and the Ducrots journeyed extensively to India, China, Laos, Myanmar, and many other countries, taking with them paying groups of well-heeled and cultured visitors—most of whom already were, or eventually became, their friends—to see architectural sites and to shop in markets. On those trips, Isabella bargained for rare and fragile textiles from merchants in places such as Kashmir and Isfahan, amassing a singular collection. Her treasures range from seventeenth-century Tibetan prayer shawls to fragments of Egyptian cotton dating possibly to the ninth century. Vicky collected Indian miniature paintings, becoming a self-taught expert. On their travels in Yemen, Uzbekistan, and elsewhere, the Ducrots gathered cuttings of wild roses—transporting damp stems in their suitcases before planting them at their country house, in Umbria, where they tended a garden exclusively dedicated to the genus. It still supplies flowers for Isabella’s apartment.

Despite her late start, and even later recognition, Ducrot’s artistic flowering has been immensely productive. Andrea Viliani, the director of the Museo delle Civiltà, in Rome, which will exhibit a selection of Ducrot’s works alongside examples of historical textiles from its own collection this summer, told me Ducrot is fortunate that her preferred technique and materials remain relatively easy for her to manage, compared with, say, sculpting metal or painting with oils on heavy canvases. “Her work is easy to hold, and easy to paint, and easy to store,” Viliani said. “It is very convenient that she chose something so soft.” Sadie Coles, a gallerist in London who presented a solo show of Ducrot’s work last year, and is currently hosting another, first encountered the paintings in a booth at Art Basel, in 2022. She bought one of Ducrot’s landscapes without knowing anything about the life of the artist. “My initial response was just how fresh it was,” Coles told me. “I would never have guessed it was made by a then ninety-one-year-old! There’s a sense of play, of texture, of discovery.” Ducrot’s works, Coles added, “feel so full of sex, intimacy, and erotic charge.”

In an introduction to a catalogue about the “Tendernesses” series, the Italian scholar Emanuele Dattilo writes that people are frequently amazed to discover that the creator of such explicitly sensual works is “a lady who is well over the age of eighty.” Of course, this reaction reveals as much about the limitations of the observer’s imagination as it does about the voluptuous reaches of Ducrot’s. We tend to assign to the elderly—and especially to elderly women—the vague, and often diminishing, attribute of wisdom, thereby suggesting that their own creative, intellectual, or erotic evolution has come to an end, and that their sole remaining role is to give advice to others. Ducrot’s work and life offer an alternative possibility: that an individual might remain wide-eyed and open to experience—in an enduring state of naïveté, and with a capacity to be joyfully surprised—until the very end.

The Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, which was constructed over several centuries and occupies most of a block, remains the home of the aristocratic family for whom it is named. The clan’s most prominent member, Pope Innocent X, was immortalized by Velázquez in a celebrated portrait painted around 1650. This masterpiece is still on display at the palazzo, in one of several splendidly ornate rooms downstairs that show off the family’s art collection.

On our first evening together, Ducrot welcomed me into her apartment’s unfolding series of cozy, inviting rooms, which were filled with overstuffed sofas, Art Deco armchairs, and modernist tables by Alvar Aalto. Choice ceramics and glassware were arranged on mantels and tables. There was a yellow ceramic dish by Picasso; a white glazed Ecce Homo made by Ducrot’s son Giuseppe, a sculptor who specializes in religious iconography; and a medieval Islamic dish showing a rider on horseback, a gift from her other child, Enrico, who now runs the travel business. Art works by friends hung on the walls. There was a portrait of Ducrot, from about forty years ago, by Maro Gorky, the daughter of Arshile Gorky, and a 1977 pastel drawing of a lotus flower by Cy Twombly, who, along with his aristocratic wife, Tatiana Franchetti, often travelled with the Ducrots. (The Twombly is inscribed “For Isabela.”) There were also dozens more Baroque paintings, many dating to the seventeenth century and acquired in the nineteen-eighties and nineties, when such works were unfashionable. A shadowy, thorn-crowned Christ being taunted by a muscled thug, attributed to Annibale Carracci, hung in Vicky Ducrot’s still intact bedroom. The prize of the collection—a pallid, recumbent, half-naked Cleopatra, by Artemisia Gentileschi—was on loan to a museum, leaving a ghostly rectangle of space on a wall near the kitchen, where a litter box was discreetly positioned.

Ducrot asked her housekeeper, Shanthi Wijesundara, to pour us glasses of champagne, and we settled side by side on a sofa. She wore an oversized olive-green sweater, wide-legged black satin pants, and chunky pale-pink sneakers; her hair was white and cut in a blunt, chin-length bob with a center part, and around her neck she wore a gold chain with a pendant of green glass. She was chic and easy in her manner, but life at her age is far from effortless, she said. Since Vicky’s death, Ducrot has been increasingly dependent upon Wijesundara, who has worked for her for forty years. “She washes me,” Ducrot told me at one point. “I am completely in her hands.” As we sipped our champagne, Ducrot explained that the happiness she felt was not unqualified. “I am terrified also, naturally, because friends of mine, old people, are dying,” she said. “But happiness is another thing. I think I am helped by the words that come to me—words are more generous with me now.”

Though Ducrot is best known for her paintings, she has also flourished, belatedly, as a writer of essays and short stories. In “The Checkered Cloth,” published in English translation in 2019, Ducrot analyzes a painting of the Annunciation by Simone Martini, the fourteenth-century Sienese artist. Ever a connoisseur of textiles, she focusses on the exposed lining of the angel Gabriel’s fluttering cloak, which has a checkered pattern—a design that, she argues, has long been associated with women, children, and the insane, rather than with heavenly visitation. In “Twenty-two Places of the Soul,” published in 2022, Ducrot dilates on the “triune” nature of fabric, describing the warp, the weft, and the empty space trapped between them as a metaphor for the Holy Trinity. Elsewhere, she compares weaving to the generative union of masculine and feminine. Every morning, between eight-thirty and ten-thirty, Ducrot writes before descending to her studio. “During the day, I am absolutely normal,” she said. “But in the morning I write very intelligent things.”

Dinner consisted of traditional Neapolitan food: lightly fried arancini with tomato sauce, followed by a savory pie. We ate around a coffee table instead of at her formal dining table, which is more frequently used for laying out her larger works of art. Ducrot keeps it covered with a canvas tablecloth that she has painted with red and white stripes; rather than cleaning it when it gets dirty, she simply adds another layer of paint.

The meal was the first of several that I shared with her that week. One visitor after another came by, creating an ever-evolving salon. I met her sons, both of whom live in Rome; her older brother, Paolo, who is ninety-six, and still walks to her apartment from his home near the Piazza Navona (their younger sister, Schatzy, who is ninety-one, lives in Naples); two of Ducrot’s four grandchildren; a tax-law adviser and friend of more than thirty years, who travelled with the Ducrots multiple times; and a new art-dealer friend whom Ducrot had warmly absorbed into her circle. All were greeted with porcelain cups of scented tea or chilled champagne in pretty colored glasses.

We also spent many hours alone, during which Ducrot was irreverent, confiding, and emotional, our conversation interrupted only by the occasional wailing of one of her cats, Evita—a diminutive, ancient creature who stiffly roamed the apartment as if lost. “She is the same age as me,” Ducrot said, in a low voice. The cat sometimes unleashed a penetrating yowl that reminded Ducrot of her husband’s final days. “He approached death furiously,” she said. Having witnessed that, she was bracing for similar anguish herself. “I will be more near to Vicky,” she said, explaining that she didn’t mean this in a supernatural way—although she was devoutly Catholic in her girlhood, she no longer believes in an afterlife. She meant that, after a long life with Vicky, she would feel a fitting sympathy with him at the end. “Love is productivo—love produces love,” she said.

It became clear that although Ducrot’s late-arriving fame has gratified her, it is also, in a way, meaningless. Adam Weinberg, a former director of the Whitney Museum, is planning a big exhibition of her work at the Madre, a museum of contemporary art in Naples, in collaboration with the Madre’s director, Eva Fabbris. This home-town retrospective—the honor of a lifetime for a younger artist—is scheduled for 2026, and is therefore not something that it makes sense for Ducrot to anticipate. “It is too far away,” she told me. Her words reminded me of the final paragraph in “Women’s Life,” a slim memoir that she published in 2021, which I had just reread on the flight to Rome:

When I reminded her of this passage, she said, “It’s very true. Yesterday, I said, ‘I hope that Rebecca is coming before I die.’ This is very logical! I live in a kind of metaphysical way. I am already in another dimensione.”

Ducrot grew up in Montedidio, a graceful district of Naples that is the site of the city’s ancient Greek settlement, in an apartment on an upper floor of a palazzo whose hereditary owner, the Principe Gerace, was a client of Ducrot’s father, a lawyer named Nino Mosca. Her mother, Maria Luisa Giordano, was descended from a noble but much reduced family. (It is family lore that when Ducrot’s parents met, in Capri in the nineteen-twenties, her mother may have been working as a courtesan.) Her father’s legal practice didn’t make the family rich, but they nonetheless inhabited bourgeois circles in Naples. Ducrot told me that although the city maintained “medieval” social norms in her youth, with young women requiring a male escort merely to venture outside, “people were fascinated by my mother, because she dressed in a way that was very elegant and very free.” In an act as spontaneous as Ducrot’s own work with textiles, her mother would fashion dresses for Ducrot and her sister by pinning together curtains.

Naples was heavily bombed during the Second World War, and the family left for the relative safety of Sorrento, a seaside retreat along the Bay of Naples, where they occupied the servants’ quarters of a villa belonging to an exiled Russian princess. In the evenings, Ducrot and her mother would have tea with the princess on the terrace and gaze at the city across the bay. “I remember my mother saying, ‘I see a fire—perhaps it is near our house,’ ” Ducrot said. “And our house was bombed, and we lost it.” When they returned, after the war, only one corner of the Palazzo Gerace remained standing, its ornate doorways splintered and its windows blown out. “My father asked the Principe, ‘Can I live here with my family?,’ and he said yes,” Ducrot recalled. “Nobody would think to live that way.” The family inhabited the ruin “as if it were the Palazzo Doria”; her mother created a bathroom in what had once been the library.

Ducrot was expected to make a suitable marriage upon graduating from high school. Paolo, her brother, told me, “Everybody looked for her at the beginning of parties and dances—she was known as one of the great beauties of Naples.” But when Ducrot was around seventeen, and having an aperitif at the Excelsior hotel, she began coughing up blood. “My mouth was invaded by warm liquid,” she writes in “Twenty-two Places of the Soul.” “I was able to slip into the next-door bathroom, let that unstoppable hot, flowing matter flop into the sink.” It was tuberculosis—an unspeakable disease in Naples, which had been blighted by the plague in the seventeenth century. Ducrot, fearful of being considered tainted, concealed her condition. Every two weeks, she sneaked off for a treatment that involved injecting oxygen via a syringe into her rib cage. It took fifteen years before she was declared cured.

Ducrot was around thirty when she fled the confines of Naples for the freedom of Rome, where “nobody knew anything about me.” (She still relishes the capital’s relative anonymity: “In this palazzo, I know about ten people. I never run into them. For me, it’s fantastic.”) She worked as a receptionist at I.B.M., at an office on the exclusive Via Veneto, and fell in with a group of intellectuals that overlapped with the likes of the novelist Alberto Moravia and the poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. “They were very chic, very elegant, and very leftist,” she said. “I was not on the right or the left—I was nothing. But I was happy with them.” It was the era of Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita,” and the women of Rome, married or otherwise, were bolder than those Ducrot had known in Naples. At least at first, she told me, “I was not a free woman. I did not have lovers.” When she finally became involved with a man, a leftist editor, she asked him one day to drive her to church so that she could confess her sins. Ducrot didn’t have money to spare, and was of necessity resourceful. When she was invited to a dance at the Palazzo Farnese, one of Rome’s grandest palaces, she improvised a dress from a length of fabric, just as her mother had done with curtains.

Vicky, who was working for the airline KLM, not far from Isabella’s office, began courting her. Vicky was also from the south of Italy—Palermo, in his case—but he was wealthy: his family owned a furniture company that made fittings for top hotels and luxury transatlantic liners. One day, Isabella joined him, his sister, Sandra, and several of their friends for a walk in the countryside. A man who had brought along his toddler son was flummoxed when the child soiled his pants and began to cry. Isabella swept the boy into her arms, hitched up her skirt, and waded into a nearby pond, washing him clean until he began laughing. Sandra, now a ceramicist who lives in Paris, told me, “She looked like a goddess, and she did the right thing, and so naturally. Vicky was looking at her, too. And I said, ‘You ought to marry this woman.’ ”

A few months later, Vicky proposed. “I was not in love, but I needed to be protected,” Ducrot recalled, adding that he promised her, “You can cry in my arms.” She told me, “This was really what I wanted. He didn’t say, ‘You are the best, you are a queen.’ He said, ‘You are. And it’s my joy.’ ” Her life changed dramatically, in scope and in resources. Vicky’s mother gave the newlyweds an apartment in Trastevere, a bohemian neighborhood in Rome, as a wedding gift, and took Ducrot shopping for couture in Paris and for jewels at Bulgari. Sixteen months after the couple’s wedding, Enrico was born, with Giuseppe arriving eighteen months after that.

Soon after Ducrot married Vicky, she showed him some autobiographical short stories that she had written, and textile designs that she had drawn. He was kindly but dismissive, she told me, and Ducrot set such projects aside for decades. “I was not offended,” she told me. “He had the feeling that he was protecting me. It was his way to show love.” Instead, she devoted herself to creating a gracious home and to sparking enthusiasms in Vicky, a serial autodidact. She recalled, “Once, I was alone in Florence, and I saw a small Baroque painting, and I called and said, ‘Vicky, I saw a beautiful, interesting painting,’ and he said, ‘Don’t buy it, we don’t need a Baroque painting.’ ” She bought it anyway, and he went on to acquire more than forty others, and to verse himself deeply in that period of art. Vicky’s introduction to a published catalogue of the Ducrot collection begins with a bracing confession: “To collect, and this can be applied to all kinds of collecting, whether match boxes, playing cards, narwhal teeth or pipes, implies a desire to own and accumulate property, and ultimately is an expression of egotism and vanity.”

Vicky was conservative in his politics, but in other ways he was more permissive than many Italian husbands. “He loved me, and he let me do what I wanted,” Ducrot told me. When she wanted to ride a bicycle around Rome, he told her that it was unsafe, but he turned a blind eye when it became her preferred mode of transportation. Marriage gave Ducrot both security and freedom. “I remember that I thought, Now that I am married, I can fall in love with other people,” she said. “It was very practical.” Once Ducrot entered élite Roman society, she found herself surrounded by other men of intelligence and cultivation. Her marriage was long and successful, but she told me that when her friends wax sentimental about how much she and Vicky must have loved each other she cuts them off—they are missing the point. “I always say, ‘Vicky gave me, for sixty years, every day, something to eat.’ ”

Throughout the Ducrots’ marriage, they spent weeks at a stretch travelling. Isabella estimates that she has been to India sixty times, and also to numerous places now essentially off limits to tourists, including Syria. In Afghanistan, she visited the imperial hilltop retreat of Istalif—“Positano-on-Hindu-Kush,” Vicky once described it in a photo album—and the Buddhas of Bamiyan, whose sandstone robes looked to Isabella “like vortices of lines.” (The Taliban destroyed the Buddhas in 2001.) During these expeditions, it fell to Isabella to insure that tour-group members were satisfied with their hotel rooms, and to supply whiskey sours after a long day of sightseeing. In the course of her travels, she said, “I learned many things, and I developed my sensibility.”

Enrico and Giuseppe occasionally came on these trips, but more typically they were left behind with babysitters. Ducrot told me that she enjoyed her children, but also cherished her life apart from them. “The reality is that I preferred to be with my friends than with them,” she explained. “It was not my maximum amusement to be with them.” If someone wonders aloud to her if the embrace in a “Tendernesses” painting represents a mother and a child, she quickly disabuses them. She told me, “I always thought that Proust, when the mother went after giving him the good-night kiss, cried not because he was so sad that the mother left but because he understood that she was preparing to amuse herself with much more interesting people than himself.”

Among her close friends was Patrizia Cavalli, the poet, who died two years ago. Cavalli once composed a poem for Ducrot titled, in English, “To Weave Is Human,” in which the warp is personified as male and the weft as female. (“She meets him just to leave him, / and leaving him she meets him; / he suffers her, he’s blameless, / and stands firm in his place.”) Tatiana Franchetti, the wife of Cy Twombly and an artist herself, who died in 2010, was the first person to encourage Ducrot to resume a creative life. The very first painting Ducrot made, in the eighties—which, with a few strokes of ink on Chinese paper, depicts two reclining lovers—hangs in her living room. Another female friend who encouraged Ducrot’s nascent vocation was Cristina Bomba, a clothing designer and the owner of a boutique near the Piazza del Popolo. Bomba told me that she was visiting Ducrot’s home to peruse her textile collection when she saw a patchwork children’s blanket that Ducrot had crafted. “I couldn’t sleep that night because I was thinking about this blanket,” she recalled. “Every little piece of fabric was so beautiful, and I was saying to myself, ‘My God, she’s so good, she’s a genius.’ ” Bomba gave Ducrot one of her first artistic commissions: to fabricate a screen for her boutique. The object, for which Ducrot patched scraps of silk and rough linen into abstract geometries, remains in service. “She started to do exhibitions in Italy, but it was very difficult for years,” Bomba went on. “In Italy, you have to be poor and unhappy to be an artist. But she was beautiful, and she was one of the luckiest people in Rome, because she had everything she wanted—so people didn’t believe in her as an artist.”

Ducrot’s studio is a bright, high-ceilinged space behind a door that opens onto a colonnaded courtyard. All day long, visitors to the Doria Pamphilj gallery, which is open to the public, walk past it unaware. When I visited the studio, a half-completed “Tendernesses” painting, on Japanese gampi paper, lay on the studio’s floor. The breasts of a female figure were exposed; a male figure had a peacock-like crest. Her studio assistant of twenty years, Veronica Della Porta, had added a black-and-white checkered background. For the next stage, Ducrot was filling the outlines of the figures with brilliant color: pea green for the woman’s skirt and carmine for the man’s lanky legs, as though he were wearing the hose of a medieval jester. “Little by little, we go on,” Ducrot told me. “And the tenderness comes out.” On a worktable lay a smaller painting that looked closer to completion: on paper washed in rose-pink pigment, Ducrot had drawn a couple in a snatched embrace, one with yellow cascading hair, the other with turquoise fronds that radiated outward.

Elsewhere in the studio, cabinets were filled with textiles folded like stacks of laundry. In addition to using scraps from her collection, Ducrot sometimes affixes larger, garment-size pieces to a background, creating imposing shapes suggestive of kimonos or of a sultan’s robes. Nora Iosia, Ducrot’s studio manager, who has worked with her since 1996, unfolded one such work, which was taller than her. Two pieces of blue-and-white striped Japanese cotton had been placed in bold juxtaposition. Iosia told me that it had taken time for Ducrot to become comfortable with such experiments. “When I met Isabella, she was very fragile and insecure,” she said. At the time, Iosia herself had recently graduated from college, with a degree in literature and philosophy; her mother, a curator, was familiar with Ducrot and her work. “My mother told me, ‘Isabella is an incredible artist, but don’t ask her to speak, because she doesn’t know the language.’ She needed to find the words.” Until Gisela Capitain, the Cologne gallerist, visited the studio with her director, Regina Fiorito, more than three decades after Ducrot began painting, “nothing happened at all” for her outside of Italy, Iosia said. “Isabella was full of power, and full of desire, and yet nothing. It was a kind of waiting for something.”

Ducrot had been a reader since her late teens, when her illness made it impossible for her to do much more than rest at home with a book. In her sixties, she began to study philosophy in earnest, taking classes at the Pontifical Gregorian University, in Rome, and working privately with scholars. With Emanuele Dattilo, she spent long hours discussing Simone Martini, the Sienese artist who inspired her exploration of humble checkered cloth. “I appreciate Isabella’s study method first and foremost,” Dattilo told me. “It is the method of losing herself—exposing herself to a radical not understanding, and moving forward with courage. Her study of philosophy is of this kind—getting into it and then seeing what effect certain ideas or certain words have on her, above all emotionally.” Datillo went on, “What is hidden attracts her, but above all I think what attracts her is a kind of reversal of roles. . . . She continually wants to reverse high and low.”

Ducrot’s work shows a particular interest in ordinary woven materials—the kind, she has written, that are “used to protect, wrap, wash and rub the bodies of new-born babies, of women giving birth, of the elderly, of the sick.” Her inclusion of such fabrics in her art rejects the low esteem in which they are typically held, revealing their inherent dignity. Similarly, in “Women’s Life,” she writes of finally considering “the endemic ignorance that had tormented me for so many years not as a source of shame but instead as an advantage.” That shame had made it difficult for Ducrot to take herself seriously, not just as an artist but as a person. For too long, she looked to others to tell her who she was. “I think life, for women, begins at sixty,” she told me. “Because then we begin to be free.”

The last day that I spent in Rome, I left Ducrot’s apartment after we shared a lunch of pink-skinned grilled rouget, sprinkled with herbs, and eggplant that had been reduced in the oven to a deliciously sticky tar. Afterward, she wanted to take a nap, as she does most afternoons; tucked into a corner of her study is a monastic single bed, alongside which hangs a Baciccio painting of Christ as Salvator Mundi—the arrangement resembling the bedchamber of a priest, or perhaps even a Pope. When I returned, a few hours later, Ducrot admitted that she had not slept after all, but instead had sifted through old letters. She had found one from a man she had been deeply in love with during her Naples youth. This man, named Antonello, had come up many times in our conversation, flashing into view like the checkered lining on a cloak worn by an annunciating angel. He had rejected her, she had told me, and it had been a torment.

Antonello had written the letter she was holding when he was in his early twenties and she was eighteen. “It says how desperate he was, because I wanted to leave him,” she explained. “I had forgotten completely! I remembered that I loved him—that’s all.” The letter, which ran to several typed pages, subverted the narrative that Ducrot had long told herself about having been spurned. “In that moment, he really loved me,” she said, with fresh wonderment. “And I have loved him for years and years. So I forgot that he could have loved me.” The fabric of her old story was coming apart in her hands.

The discovery felt transformative, Ducrot said. “You came at a moment of my life when there is not so much more to say, and not so much more to feel,” she noted. “So, every day from tomorrow, I cannot say another life begins—no, certainly not. But, in a way, perhaps another meaning of the life is beginning.” Earlier, she had wanted to assure me of how unpredictable a very long life might be; although I told her I’d been happily married for twenty years, she observed, “We don’t know what we are going to do in life. Perhaps you will become a dancer, or leave your family, or go off with a man from South Africa”—not exactly conventional wisdom from an elder. Now, she told me, she believed it was possible to fall in love even as one was dying. “I have always thought this—that you are dying in a kind of agony, and you fall in love,” she said. “I’m sure it has happened.”

The letter in her hand, written on the fragile paper of the past, was the material evidence not just of what she had experienced in her youth but of what was animating her at this moment—our intense, extended conversation. Being very old had heightened her sense of the present. “I am already in love with you!” she told me in greeting, on the first evening I visited. If Ducrot had wisdom to impart, it concerned the trembling imperative of living fully, even without a future. “I think a person of my age cannot not be interesting,” she said. “Because we are like prisoners in a jail, and we know that we are in the braccio della morte”—on death row. She went on, “This is true of everybody—good people, intelligent people, poor people, rich people. This is an experience, to be so old.”

Lately, Ducrot has developed a new practice in her work. She takes pages of writing by others, which have long been filed away in cupboards and drawers, and sews pieces of them onto the surface of paintings—not for their content, she told me, but because of the beauty of their now illegible calligraphy. In her hands, these texts were transformed from one thing into another, just like the textiles that she once gathered from far-off places. One of Ducrot’s newest works lay on the dining table during my visit, and one morning I snapped a photograph of the painting on my phone. Only later did I take it in more fully: on a large fabric background, she had painted leaf-covered trees and an array of pots containing brightly colored, heavy-headed flowers. Tacked in the middle of the work was a cutout from a piece of paper on which tiny cursive letters had been written; the cutout was encircled by the branching arm of a tree. The leaves were heart-shaped and an autumnal brown, barely still attached to a branch—or perhaps no longer attached at all, but suspended in an ultimate moment of lightness before their fall. ♦