“There have always been women artists, it’s just that art history has not made space to study them,” says Elina Norandi, art historian and art critic, when asked about women artists in Catalan modernism.

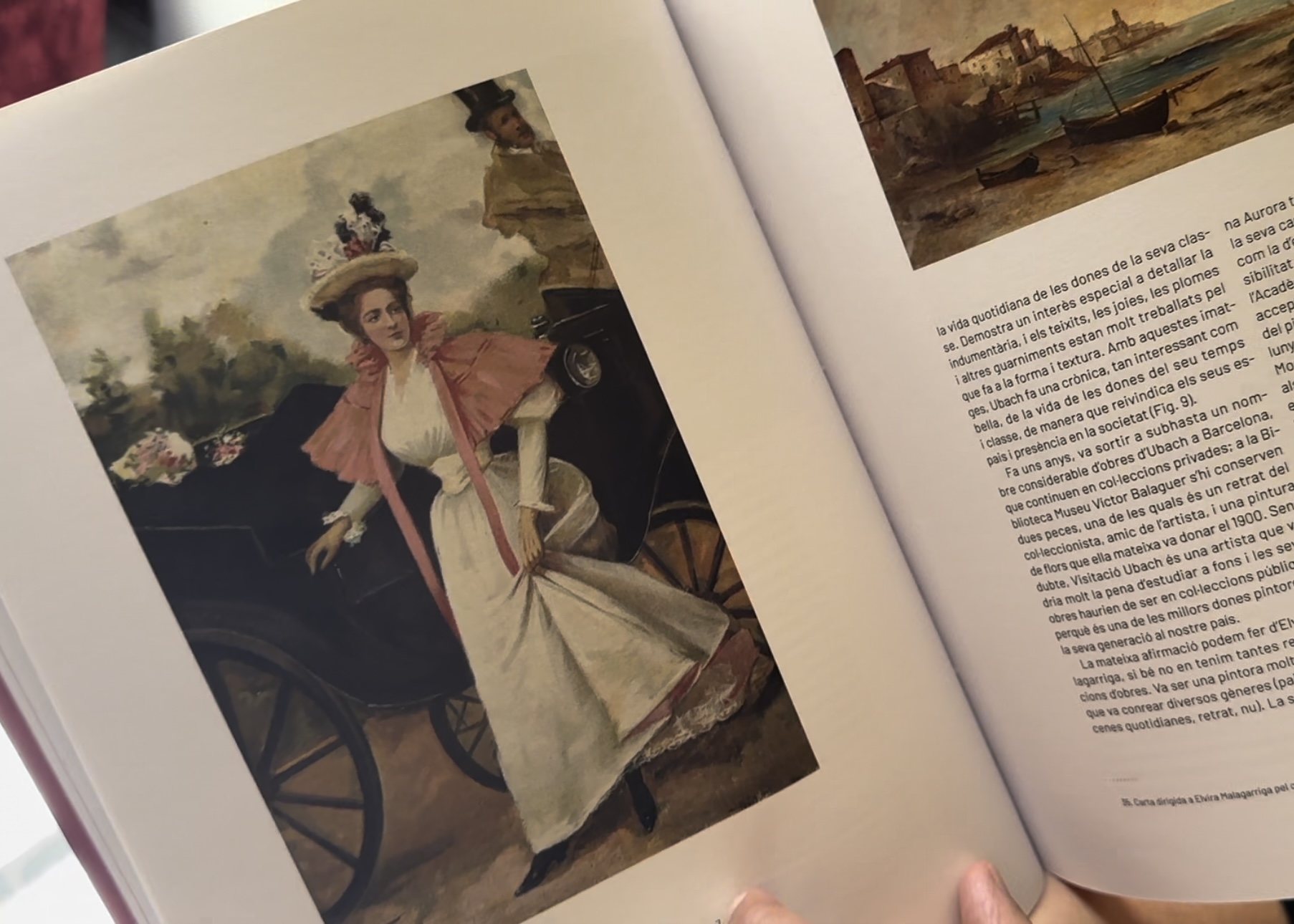

Women usually appeared in modernist paintings as muses or as bourgeoise being portrayed in daily scenes, but they were rarely behind the canvas and creating the art.

Or at least that is what has transcended art through history.

“We have records of women painting as far back as medieval times, but the patriarchy has a lot of ways of omitting and undervaluing women’s work,” Norandi adds.

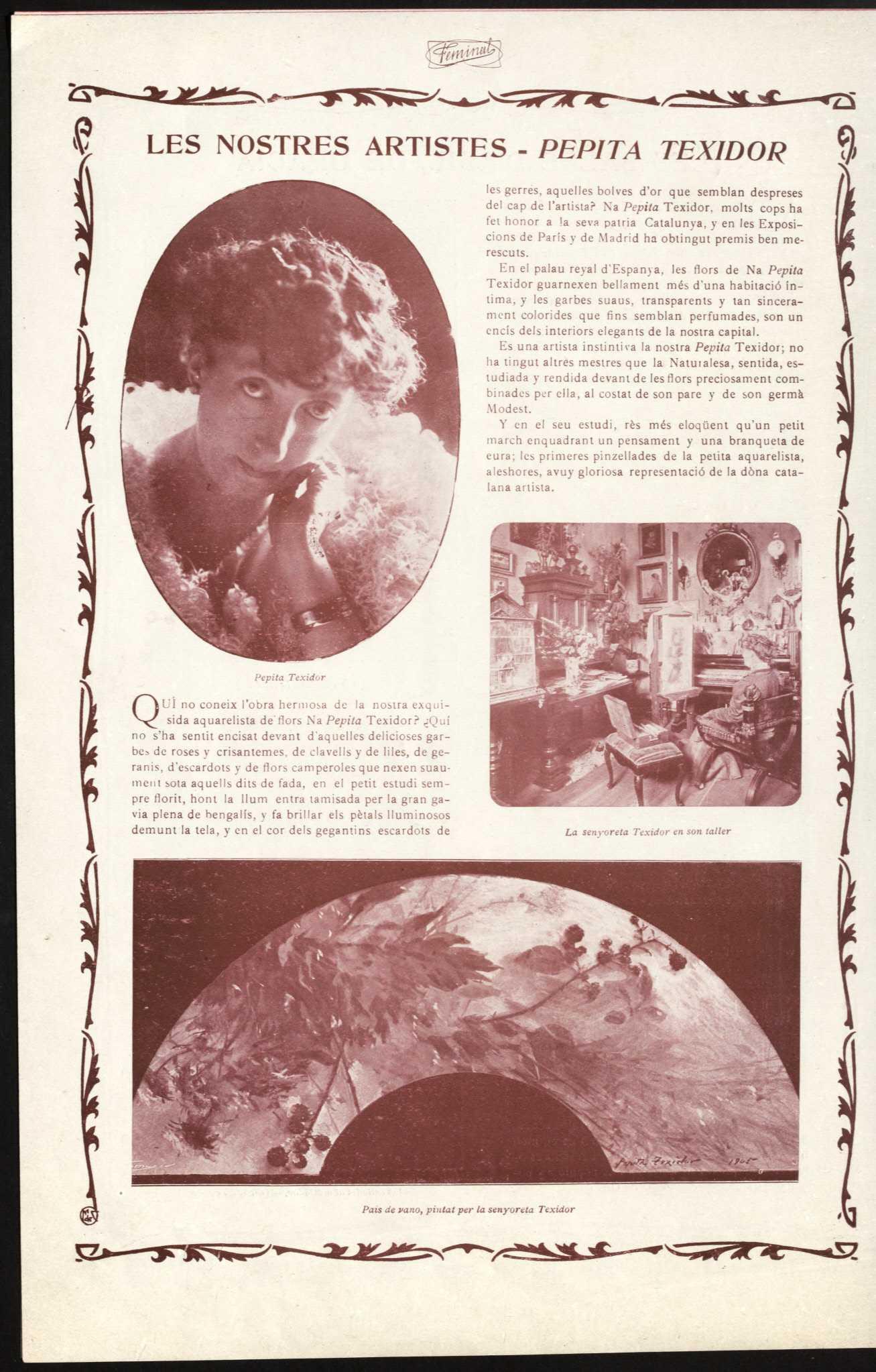

In Catalan modernism, some of the artists that have been studied the most are Lluïsa Vidal, Pepita Teixidor, and Lola Anglada, mainly thanks to the magazine Feminal.

Feminal, more than a women’s magazine

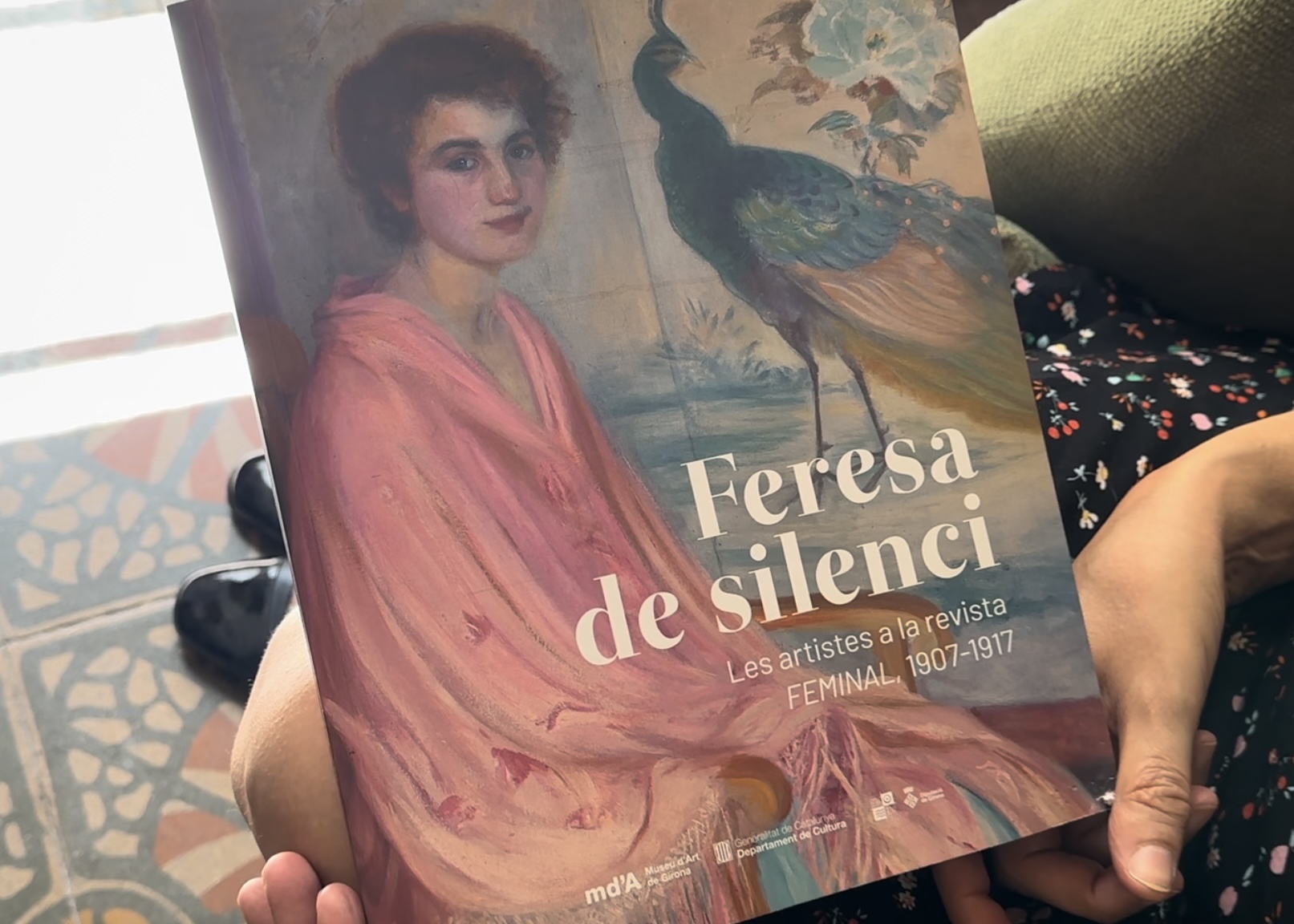

Feminal was a publication that was offered as a supplement to a popular magazine at the time: La Ilustració Catalana (Catalan Illustration).

It was a magazine created by Carme Karr, one of the most ardent Catalan feminists of the early 20th century, inspired by the magazines that already existed in Paris.

Although it was made for bourgeoisie Catholic women, there are articles about several varied topics.

In the 10 years it ran, from 1907 to 1917, Feminal published pieces about fashion and social affairs, but also stories about English suffragettes, women in sports, and in general women abroad who were participating in the public sphere.

Of course, Feminal also published about women artists.

“In a lot of the issues we see an article about the artists that has been done from their studio, with pictures of them and their artwork,” Elina Norandi explains.

“This is a treasure trove, because most of them disappeared later on and are completely unknown,” she adds.

All of this information was used by Norandi to create an exhibition in 2022 at the Museu d’Art de Girona about all the women artists who were featured in Feminal.

Young bourgeoise women

“What I saw when analyzing these articles is that all of the women featured in Feminal were young and born in the second half of the 19th century, and their moment as artists was until the start of World War 1.”

But these women did not stop painting because of the war, or not only because of that. “All of them abandoned their art once they got married,” Elina explains. “The women modernist artists that are most known today have gained such relevance in art history because they did not get married nor have children,” she adds.

Elina Norandi continues: “I believe that now we have such amazing work from Lluïsa Vidal and Lola Anglada because they were two women artists who chose not to get married. Sadly back then women had to choose to either get married and have children or have an artistic and professional career.”

These women who dedicated professionally to art were an exception, as they could get an improved art education and travel to places like Paris. But they also had to work on the proper maintenance and preservation of their own work in order to build their legacy, as well as deal with the criticism.

“If you read a critique of women artists at that time, you will see that often the men writing the pieces use the opportunity to try and flirt with the artists, as they undervalue their skills,” Elina Norandi explains.

Changing museums

In addition, when these women were criticized for their art and often compared to men, they completely erased the fact that these women did not have access to the same art lessons.

“Most of the women artists went to La Llotja, an art school in Barcelona and they did not attend the same classes as the men, mainly because they painted naked bodies,” Elina explains.

“Women were only allowed to paint flowers, or other kind of natural elements, but nothing further than that. But then they were bashed for their creations always being about ‘feminine topics’,” she continues.

Some of these women’s creations got lost between descendants moving boxes and ignorance of the artwork, but the pieces that historians have identified also have a battle of their own.

Women’s paintings are rarely featured in exhibitions, but rather stored in a museum’s warehouse.

It is not easy for them to get a space there, because the canons of Catalan modernism have been built from the point of view of Ramon Casas and Santiago Rusiñol, the most important artists of that movement.

“I know that right now it is really difficult to change the perception that has been built around modernism. How are we going to take down some of the most beautiful pieces we have in the National Art Museum of Catalonia or other museums for something that is not as known –or as good–?” Elina ponders.

“Although there is still a lot to go, I do have hope that one day we will see more equality in museum rooms,” Norandi concludes.