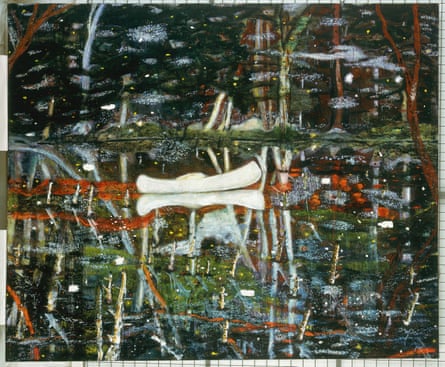

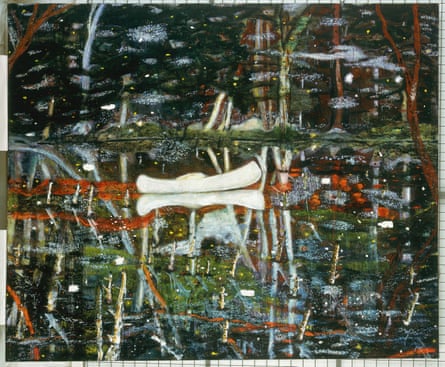

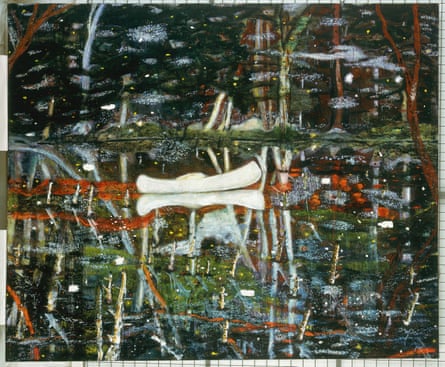

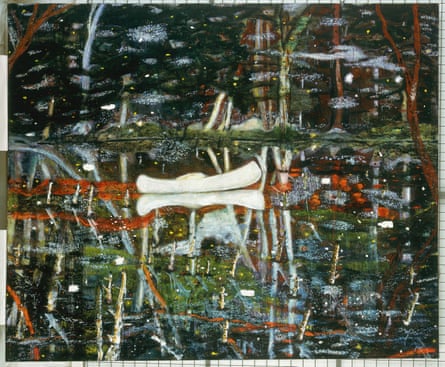

Peter Doig became the most expensive living painter in Europe in 2007, when White Canoe, his atmospheric painting of a moonlit lagoon, sold for £5.7m.

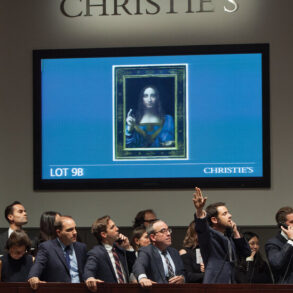

The Scot then saw his auction record broken in 2017 and in 2021 respectively, when Rosedale, his depiction of a house in a snow storm, and Swamped, another enigmatic painting of a canoe, sold for the eye-watering prices of £21m and nearly £30m respectively.

The 65-year-old artist estimates that, since 2007, his paintings have achieved combined sales of almost £380m. But he has now revealed that he has made barely £230,000 for himself from selling them.

Doig said it is collectors who are profiting, buying and selling his works on the secondary market for “crazy prices”, and he has no idea who they are because the art trade is so opaque. “It’s all very clandestine,” he told the Observer. “Some paintings are sold offshore, so it’s untraceable.”

He is now calling for more transparency within the art market, particularly to protect vulnerable young artists. Doig believes that, as with any business relationship, galleries have a duty to share information about sales with the artists who created the works: “They should be absolutely transparent in all the dealings. There’s so much secrecy, especially when the amounts start to get high. Once an artist has sold an artwork, they’ve got few rights.”

Doig said he had had a “real row” recently with one of his former art galleries after they refused to tell him who had bought his artworks.

“I wasn’t after money,” he said. “I wanted to know where the paintings had gone to. They said: ‘We can’t give you that information.’

I asked: ‘Can you at least tell me what you sold them for?’ and they refused that as well. The information is kept so secret, it’s infuriating.”

He added: “In the contemporary art world, gallerists make secondary sales of your work. This happened to me quite a lot, I found out.

“For instance, you sell a painting and then, perhaps five years later, the person who bought it resells it, and it’s usually done through the gallery because that’s the arrangement they’ve got. They may give you something, but not with a piece of paper, an invoice, which would happen in the real world.

“It’s never clear what works are traded for on the secondary market, except at auction.”

Some dealers are taking advantage of artists, he believes: “You’re much more vulnerable when you’re a young artist and you’re just so grateful to be having your work shown and sold.”

Doig was born in Edinburgh in 1959 and raised in Trinidad and Canada, studying at St Martin’s and the Chelsea College in London. He now divides his time between Britain and Trinidad, painting evocative compositions that range from jungles to snow-covered mountains.

after newsletter promotion

He is considered one of the most important painters working today, but is frustrated by people wrongly assuming that auction sales reflect what he makes from his paintings, let alone “behind-the-scene sales, which are plentiful – I’m sure at least equal – and quite clandestine”.

The secondary market did boost the value of his paintings on the primary market, he said. “But your prices would never, ever match or even get close to what happens on the secondary market, a world of its own.”

Th eDesign and Artists Copyright Society (DACS) states that the law of Artist’s Resale Right gives artists and their beneficiaries the right to a payment when their work is resold for £1,000 or more through a gallery, auction house or art dealer. It has enabled Doig to keep some record of sales: “But the maximum you get with a DACS sale is tiny.” Works sold for £2m or more will receive a maximum royalty payout of £12,500. “And if someone sells a painting offshore, you don’t get that.”

When Doig was a struggling artist, he was nominated for the 1990 Whitechapel Artists Award, by Yuko Shiraishi, an artist whose husband, David Juda, runs a gallery that also represents David Hockney. Doig won, giving him “exposure that I’d never had before”.

Doig is now this year’s guest curator of the David and Yuko Juda Art Foundation Grant, which donates £50,000 to an artist to alleviate financial pressures.

He has drawn up a shortlist of seven candidates. They include a former student, Kaoli Mashio, a Japanese artist based in Düsseldorf, whose landscape paintings are “very delicate and beautiful”, and his former teacher, Tim Allen, whose abstract paintings deserve “real recognition”.

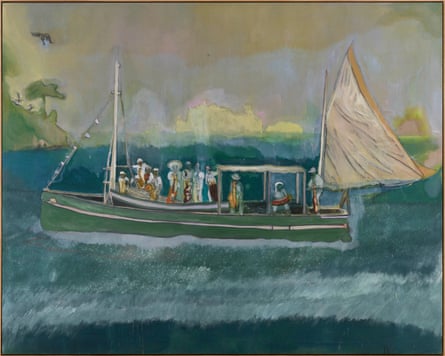

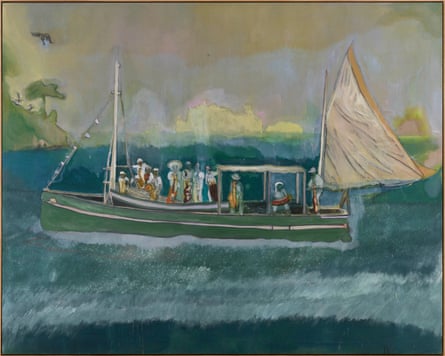

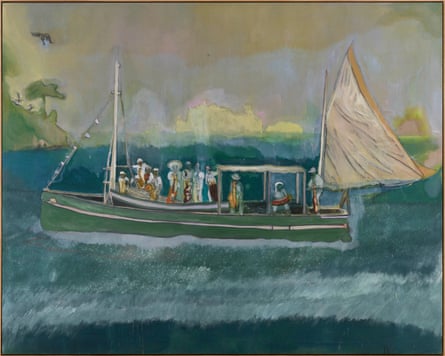

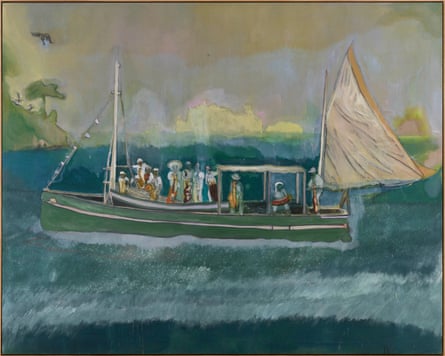

The other shortlisted artists are Jai Chuhan, whose figurative paintings remind him of those of Frank Auerbach and William Coldstream; David Harrison, whose paintings and sculptures are both “nightmarish and dreamlike”; Tam Joseph, who creates “powerful” artworks about struggles faced by the post-Windrush generation; Gavin Lockheart, who paints “reflective” pictures; and Alan Vaughan, who creates “concepts” for carnival bands.

A panel of judges – including former Tate curator Andrew Wilson – will decide on the winner next week. An exhibition of the shortlisted artists will be held at Annely Juda Fine Art in London from 10 September.