Abstract

Public discussion enhances people’s political efficacy, which is also true on social media. While past studies have focused on the effects of the size and frequency of interactions on this relationship, Heise suggested that social network quality may be more important. Therefore, the present study conducted an online survey that measured certain variables, including number of persons interacting, interaction frequency, public discussion involvement, social network evaluation, and internal political efficacy, for 624 social media (WeChat) users. It aimed to determine how these variables affect the generation of internal efficacy. The results revealed that number of persons interacting increases people’s public issue involvement and thus their internal political efficacy; moreover, they indicated that this relationship is mediated by the frequency of interaction and social network evaluation, with the latter having a stronger effect. A more critical factor in whether public discussions on social media enhance people’s internal political efficacy may be who they interact with and with whom they discuss things. This study’s findings demonstrate how affective control is embedded in the relational model of the influence of public discussions in social media on internal political efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past 15 years, many studies have focused on the impact of social media use on individuals’ political participation, which mainly manifests at the psychological level in terms of its effect on political efficacy, especially internal political efficacy (Coleman et al. 2008; Velasquez and LaRose 2015; Bernardi et al. 2023). The COVID-19 pandemic, which required people to maintain social distance over a long period while relying on social media communication, objectively increased the probability and effect of this influence. Whereas most relevant studies have examined the effects of social media use on political efficacy from the perspectives of information, expression, and instruments (Zhou and Pinkleton 2012; Chan et al. 2019), said effects have been less studied from the perspective of the communication mechanism itself. Therefore, the present study attempted to examine how social media use affects people’s internal political efficacy as well as how the affection control of social networks plays a role in this process. Its examination started from the variables directly related to the interaction process, such as number of persons interacting, interaction issues, and interaction frequency. Habermas’s theory of the public sphere (Habermas 2022) and the theory of affection control (Heise 2016) provided the theoretical basis for the study.

Habermas’s theory of the public sphere implies that the ability to enter public spaces and participate in discussions is a manifestation of people’s political competence (Habermas 2022). Furthermore, Fuchs directly demonstrated that digital public spaces are generated on platforms of various types and that the interaction of interpersonal networks on these platforms has a substantial impact on political efficacy (Fuchs 2021). The size of social networks and the topics of discussion have been crucial factors in relevant studies (Boulianne 2020; Gil de Zúñiga et al. (2021)). Moreover, in recent years, many studies have demonstrated that social media is first and foremost an emotional space. Research on information cocoons, echo chambers, and polarization effects demonstrated that, unlike the traditional model of opinion leaders, emotional contagion and affection control influence the formation of people’s political efficacy through a special type of social network interaction (Ognyanova 2022).

Ultimately, this study attempted to answer the two research questions:

-

(1)

How do the size of individual interactions and the degree of involvement in public issues on social media affect the generation of an individual’s internal political efficacy?

-

(2)

How do interaction frequency and the individual’s evaluation of social networks affect these relationships?

Literature review and hypotheses development

Number of persons interacting, public issue involvement, and internal political efficacy

Number of persons online interacting is an important indicator of one’s social influence (Farivar et al. 2021), and it also affects one’s internal political efficacy (Mashud et al. 2023). Many studies have demonstrated that an individual’s online social network (OSN) affects their political participation (Boulianne 2020); thus, the size, composition, and frequency of interactions on social networks are crucial variables to measure. For example, Gil de Zúñiga et al. (2014) revealed that the scale of online interaction directly affects people’s ability to participate in politics. Moreover, Chan et al. (2019) compared the relationship between OSNs and political social networks based on data from six Asian countries and noted its impact on political efficacy. Furthermore, Halpern et al. (2017) compared the differences between Facebook and Twitter in terms of political efficacy enhancement and concluded that Facebook enhances collective efficacy while Twitter enhances internal efficacy. These studies have all indirectly pointed to a relationship in which differences in social network creation and size on social media affect the formation of individuals’ political efficacy. A separate research project conducted by Gil de Zúñiga et al. (2021) revealed that the type of discussion topic affects the generation of political efficacy. Here, the following question arises: Does the scale of individuals’ interactions on social networks affect their probability of entering public issues and thus their generation of internal political efficacy? Accordingly, this study proposed the following hypothesis (H):

H1: Number of persons interacting affects public issue involvement, which in turn affects the internal political efficacy of individuals, while public issue involvement mediates the relationship between number of persons interacting and an individual’s internal political efficacy.

Mediating role of interaction frequency

In the chain of relationships formed by the three variables of number of persons interacting, individual public issue involvement, and internal political efficacy, the frequency of interaction has dynamic characteristics, and studies have examined what happens to it. Valenzuela et al. (2018) concluded that the frequency of social interaction can directly affect an individual’s political participation, while Hyun and Kim (2015) found that said frequency affects people’s access to news topics and related political discussions, which ultimately affects their political participation. Regarding political efficacy, Gibbs et al. (2021) found that students’ participation in budget discussions significantly increased their sense of political efficacy. Similarly, Chan et al. (2012) found that individuals’ intake of information regarding public issues relied on their active participation in relevant issues, under which their sense of political efficacy could be increased. That is, the frequency of interaction is likely to play an active or even mediating role between the scale of individuals’ daily interactions, their involvement in public issues, and their sense of political efficacy. Accordingly, this study proposed the hypothesis:

H2: Interaction frequency mediates the relationship between number of persons interacting, public issue involvement, and internal political efficacy.

Mediating role of social network evaluation

Many studies have indicated that the influence of social media on users’ attitudes and behaviors toward public events is primarily driven through the power of emotions and sentiments (Duncombe 2019; Boler and Davis 2018). This power is even greater than that of the influence of cognitive factors (Han and Xu 2022). Moreover, social media communication relies heavily on the construction of one’s own social network, which can play a critical role in one’s cognitive and affective production. Those who build relationships with more people of higher ability, potential, and dynamism in their social networks are more inclined to have access to all types of public issues and thus increase their political efficacy (Kahne and Bowyer 2018). Weeks et al. (2017) analyzed the influence mechanism of opinion leaders on public attitudes in social media, seeking to answer the question of what types of individuals become influential. Then, the relevant measures of ability, potential, and activation in affection control theory became the basis for further research (Heise 2016). It indicates that these three dimensions can serve as valid indicators for measuring affective control in social networks, and thus we subsequently used the abbreviation EPA for measurement and effect analysis. Accordingly, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H3: Individuals’ EPA ratings of their own social networks mediate the relationship between number of persons interacting, public issue involvement, and internal political efficacy.

Method

Sample and data collection

This study employed an online questionnaire to collect data on the everyday social media practices of 624 WeChat users in China, carried out through the website (https://www.wjx.cn) in October 2022. WeChat was selected as the primary social media platform due to its status as the most widely used among the Chinese populace. Additionally, its private nature made it a fitting choice for exploring how daily interactions on social networks influence political efficacy. To ensure the integrity of the data, measures were implemented to track IP addresses, devices, and to impose user restrictions, along with employing logical questions to prevent duplicate entries and invalid responses. The survey achieved a commendable valid response rate of 94%, with an average completion time of 522 s. Table 1 presents the final sample’s demographic data:

Measurement

Internal political efficacy

Niemi et al. (1991) asserted that internal political efficacy refers to beliefs about one’s own competence to understand and participate effectively in politics; that is, it includes both beliefs and competencies. Further adopting Boulianne’s development of internal political efficacy measures (Boulianne et al. 2023), the present study opted to measure the construct using the following four question items: (1) ‘I feel that I have a pretty good understanding of the important issues discussed by my friends’; (2) ‘I consider myself well-qualified to participate in group decision-making processes’; (3) ‘I feel that I do as good a job in the group decision-making process as most other people’; and (4) ‘I think that I am well-informed about the issues discussed by my group’. Survey respondents were asked to respond to each item by selecting a number on a 0–10 scale, where 10 indicated the highest agreement. An indicator of internal political efficacy was obtained by summing the option scores and dividing them by 4. The internal consistency coefficient of the four items was 0.856 (Cronbach’s alpha). The average and standard deviation of this metric are shown later in Table 2.

Number of persons interacting

This research assessed individual interaction patterns by tallying their daily exchanges as a measure of social engagement. The central inquiry posed was: How many individuals do you regularly interact with in your WeChat circle, encompassing private messages, group chats, reactions, comments, and shares? Participants responded using a matrix format with the following categories: 1. family members; 2. friends; 3. classmates/colleagues; and 4. engaging and insightful individuals. Number of persons interacting was categorized into the following groups: 1. one individual, 2. two to three individuals, 3. four to seven individuals, 4. eight to fifteen individuals, and 5. sixteen or more individuals. The gathered responses were sorted in increasing order, and the sums from the four categories were averaged to create a measure indicating the level of social engagement. The mean and standard deviation of this variable are presented in later in Table 2.

Public issue involvement

To guarantee that the group involved in public issue discussions was consistent with that of number of persons interacting, we employed the following question to gauge public issue engagement: In the past year, have you discussed the topics listed above with the individuals mentioned (0 = not at all; 5 = frequently)? The choices included: (1) social issues like the violent assaults on women in Tangshan and the chained woman in Xuzhou; (2) the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) details regarding the Nobel Prize; (4) the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine; (5) concerns about environmental preservation; and (6) the energy crisis. In essence, these choices encapsulated the key social and international occurrences that might have engaged the Chinese public over the last year. To derive the index of public issue involvement, the scores for each category of event were totaled and then divided by six. The average and standard deviation for this variable can be found later in Table 2.

Frequency of interaction

The term “frequency of interaction” often arises in research concerning online social networks and social capital (Agarwal and Bharadwaj 2013). In this study, we assessed this concept by posing the question: How frequently do you engage in private messaging with the close friends mentioned above on a daily basis? The options for responses included: 1. multiple times each day; 2. once a day; 3. two to three times weekly; 4. two to three times each month; and 5. infrequently or hardly at all. The data were reversed to arrive at the ultimate measure of interaction frequency. This metric serves as a direct reflection of how often private, one-on-one conversations occur, thereby providing a clearer picture of how these profound interactions influence internal political efficacy. The statistical data concerning this indicator will be detailed later in Table 2.

Social network evaluation

We utilized the EPA semantic differential scale, a tool that has gained traction in affection control research in recent years, to assess how individuals perceive their own social networks (Heise 2016). The particular measurement query was framed as follows: Kindly provide an overall assessment (0 = extremely poor or inactive; 5 = excellent or highly active) of the aforementioned groups with whom you engage most regularly on a daily basis. The choices were classified under EPA, and the outcomes of these choices were totaled and divided by three to derive the metric for assessing individual social networks. The statistical data pertaining to this metric can be found later in Table 2.

Statistical analysis

Initially, a Pearson correlation test was conducted on the primary variables to assess their suitability for the model. Then, the three main hypotheses were tested using the PROCESS plug-in Model 80 in the SPSS software package.

Results

Correlation test results

Table 2 displays both the descriptive statistics and the Pearson correlation results in a two-by-two format. The findings reveal significant correlations between internal political efficacy and several variables: number of persons interacting, involvement in public issues, frequency of interactions, and the evaluation of social networks. The correlation coefficients were 0.288, 0.488, 0.276, and 0.463, respectively. p-values were all less than 0.01.

Hypothesis testing

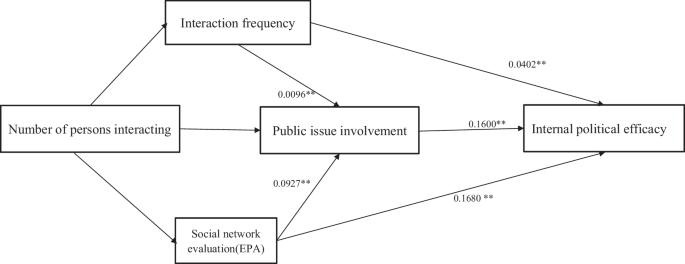

Subsequently, a mediation effect analysis was conducted utilizing Model 80. The findings demonstrated r = 0.5576, R2 = 0.3109, F = 69.8232, with degrees of freedom df1 = 4.00 and df2 = 619.00, MSE = 2.2940, and a p-value of 0.0000. These statistics suggest that the baseline model performed admirably and that the outcomes are valid. A deeper examination of the results uncovered that the direct impact of the number of individuals engaged on a person’s internal political efficacy was 0.2184 (SE = 0.0894, t = 2.4435, p = 0.0148), with the confidence interval not crossing zero (LLCI = 0.0429, ULCI = 0.3940). Additionally, the influence of involvement in public issues on an individual’s internal political efficacy was measured at 0.5688 (SE = 0.0827, t = 6.8795, p = 0.0000), once again indicating that the confidence interval did not include zero (LLCI = 0.4064, ULCI = 0.7311). A deeper examination of each influence chain uncovered the following: (1) Involvement with public issues magnified the impact of the number of individuals interacting on personal internal political efficacy, resulting in an effect size of 0.1600 (LLCI = 0.0964, ULCI = 0.2364); hence, H1 was validated; (2) The frequency of interaction also amplified the influence of the number of persons interacting on individuals’ internal political efficacy, yielding an effect size of 0.0402 (LLCI = 0.0094, ULCI = 0.0803); and (3) Social network evaluation (EPA) enhanced the impact of the number of persons interacting on personal internal political efficacy, with an effect size of 0.1680 (LLCI = 0.0929, ULCI = 0.2563). Additionally, further mediated effect testing indicated that (4) Interaction frequency elevated the influence of the number of persons interacting on public issue involvement, which in turn affected individuals’ internal political efficacy, with an effect size of 0.0096 (LLCI = 0.0019, ULCI = 0.0208); confirming H2. and (5) Social network evaluation (EPA) also increased the effect of number of persons interacting on public issue involvement, ultimately influencing individuals’ internal political efficacy, with an effect size of 0.0927 (LLCI = 0.0541, ULCI = 0.1406); thus, H3 was confirmed. Table 3 presents the Model 80 mediation results in detail:

The findings suggest that the mediating effect size of social network evaluation (EPA) on both social network size and internal political efficacy (0.1680) and social network size, public issue involvement, and internal political efficacy (0.0927) was greater than the effect of interaction frequency (0.0402, 0.0096). The results fully demonstrate that social network evaluation (EPA) has a more significant effect in the formation of individual political efficacy than interaction frequency. Figure 1 depicts the effect relationship among the variables:

Discussion and conclusion

This research explored the impact of social media interactions on individuals’ internal political efficacy. It revealed that the size of one’s social network plays a significant role in shaping political engagement by affecting how deeply individuals participate in public matters. This relationship is mediated by how often they interact and how they evaluate their social networks. Notably, the evaluation of social networks proved to be a stronger predictor than the frequency of interactions. This subtly suggests that affective control theory might offer a more compelling explanation than public engagement theory regarding how social media influences people’s political efficacy.

Furthermore, this study found that number of persons interacting affects the generation of individuals’ internal political efficacy and functions as a chain of relationships by influencing their public issue involvement (Fuchs et al. 2021; Valenzuela et al. 2012). Thus, the traditional theoretical hypothesis of the effect of social size on personal political competence in public engagement research remains valid in studies of the effect of social media use on individual micro-political competence formation. The findings also echo Gibbs et al. (2021) and Chan et al.’s (2012) analysis of engagement in public discourse as a crucial condition for generating political competence. Moreover, the discovery of the role of social frequency provides a dynamic view of the relationship between social networks, public discourse, and personal political efficacy, echoing Valenzuela and Chan et al.’s analysis of the impact of social interaction frequency in political participation and political efficacy (Valenzuela et al. 2018; Chan et al. 2012).

Additionally, regarding the role of individual evaluations of social networks in the chain of relationships of variables related to the generation of personal political efficacy, it represents an attempt to introduce affection control theory into the analysis of social media interaction mechanisms. In the past decade or so, social media has played an important role in people’s social life and political participation, and they have discovered the roles of emotions in it (Duncombe 2019; Boler et al. 2018); however, the mechanisms of affection’s influence have been less analyzed, especially the association with objective variables such as number of persons interacting and public issue involvement. This study was inspired by that of Heise (2016), and the EPA scale was used in an attempt to operationalize the practice of this mechanistic study. This analytical approach is expected to generate further discussion in similar studies.

In addition to demonstrating the influence of objective variables related to public participation on the internal political efficacy of individuals, such as social network size, public issue involvement, and interactive frequency, this study also measured the influence of individual subjective evaluation dimensions (i.e., individuals’ evaluations of their own social network from three dimensions). Finally, through its mediation analysis, it demonstrated the influence of cognitive-affective factors in individual social media interactions over objective interaction variables through the influence coefficients. The study was thus able to conclude that affection control theory may have more explanatory power than public engagement theory in explaining the relationship between individual social media use and the generation of intrinsic political efficacy. Nevertheless, this conclusion still needs to be verified by more refined studies.

Finally, this study did not limit itself to the concept of online internal political efficacy when measuring the internal political efficacy of individuals as a whole because, in the authors’ opinion, the impact of social media interactions on people’s internal political efficacy occurs not only in the Internet space, but also affects people’s sense of internal political efficacy in their offline lives, and in this sense, the two are one and the same. Thus, this study did not break down the measurement. Noteworthily, as this study was based on an analysis of WeChat, the most widely used form of social media among the Chinese public, combined with the characteristics of different social media platforms, it is possible that other social networks do not present exactly the same characteristics, which is worthy of further exploration. Moreover, in the selection of data analysis strategies and the formulation of the hypotheses, many conditional hypotheses were not listed to clearly show the main chain of relationships of interest to this study. This choice may also be worthy of discussion. Lastly, this study only addressed the effects of interaction networks and processes on internal political efficacy; therefore, for external political efficacy, more macro-level variables may need to be considered.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that in the Chinese sociocultural context, objective indicators of social network interactions, such as number of persons interacting and frequency, are far less important than indicators related to the objects of interactions (i.e., who one interacts with on a daily basis and how well one rates their competence, potency, and activity). Among those who score high on these metrics, the higher they are in an individual’s respect, the greater the influence that talking to them has, and the higher that individual’s personal perception of their internal political efficacy. Thus, it is not how many people one talks to about public events that matters; rather, it is who one talks to about them. This finding does not only connect Habermas’s theory of online public opinion from the perspective of information and Heise’s theory of respect from the perspective of people at an operational level (Habermas 2022; Heise 2016); more importantly, it also indicates that in the current information-driven space of opinion formation in cyberspace, it is still people who influence the formation of individuals’ political efficacy. This is particularly instructive for understanding the formation of individual political efficacy and public opinion formation in the cultural context of China, a society with a long tradition of political meritocracy (Bell 2012).

Data availability

Research data to support this publication are available from the author upon request.

References

-

Agarwal V, Bharadwaj KK (2013) A collaborative filtering framework for friends recommendation in social networks based on interaction intensity and adaptive user similarity. Soc Netw Anal Min 3:359–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-012-0083-7

-

Bell DA (2012) Meritocracy is a good thing. N Perspect Q 29(4):9–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5842.2012.01339.x

-

Bernardi L, Mattila M, Papageorgiou A, Rapeli L (2023) Down but not yet out: depression, political efficacy, and voting. Pol Psychol 44:217–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12837

-

Boler M, Davis E (2018) The affective politics of the “post-truth” era: feeling rules and networked subjectivity. Emot Space Soc 27:75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2018.03.002

-

Boulianne S (2020) Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation. Commun Res 47:947–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218808186

-

Boulianne S, Oser J, Hoffmann CP (2023) Powerless in the digital age? A systematic review and meta-analysis of political efficacy and digital media use. N Media Soc 25:2512–2536. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231176519

-

Chan M, Chen HT, Lee FLF (2019) Examining the roles of political social network and internal efficacy on social media news engagement: a comparative study of six Asian countries. Int J Press Pol 24:127–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218814480

-

Chan M, Wu X, Hao Y, Xi R, Jin T (2012) Microblogging, online expression, and political efficacy among young Chinese citizens: the moderating role of information and entertainment needs in the use of Weibo. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 15:345–349. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0109

-

Coleman S, Morrison DE, Svennevig M (2008) New media and political efficacy. Int J Commun 2:21, https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/172

-

Duncombe C (2019) The politics of Twitter: emotions and the power of social media. Int Pol Socio 13:409–429. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olz013

-

Farivar S, Wang F, Yuan Y (2021) Opinion leadership vs. para-social relationship: key factors in influencer marketing. J Retail Con Serv 59:102371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102371

-

Fuchs C (2021) The digital commons and the digital public sphere: How to advance digital democracy today. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 16, 9–26. https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.917

-

Gibbs NP, Bartlett T, Schugurensky D (2021) Does school participatory budgeting increase students’ political efficacy? Bandura’s ‘sources’, civic pedagogy, and education for democracy. Curric Teach 36:5–27. https://doi.org/10.7459/ct/36.1.02

-

Gil de Zúñiga H, Molyneux L, Zheng P (2014) Social media, political expression, and political participation: panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. J Commun 64:612–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12103

-

Gil de Zúñiga H, Ardèvol-Abreu A, Casero-Ripollés A (2021) WhatsApp political discussion, conventional participation and activism: exploring direct, indirect and generational effects. Inf Commun Soc 24:201–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1642933

-

Habermas J (2022) Reflections and hypotheses on a further structural transformation of the political public sphere. Theor Cult Soc 39:145–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764221112341

-

Halpern D, Valenzuela S, Katz JE (2017) We face, I tweet: how different social media influence political participation through collective and internal efficacy. J Comput Mediat Commun 22:320–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12198

-

Han R, Xu J (2022) How social media influences public attitudes to COVID-19 governance policy: an analysis based on cognitive-affective model. Psychol Res Behav Manag 15:2083–2095. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S371551

-

Heise DR (2016) Affect control theory: concepts and model. Analyzing Social Interaction: Advances in Affect Control Theory, 13, 1–33

-

Hyun KD, Kim J (2015) Differential and interactive influences on political participation by different types of news activities and political conversation through social media. Comput Hum Behav 45:328–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.031

-

Kahne J, Bowyer B (2018) The political significance of social media activity and social networks. Pol Commun 35:470–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1426662

-

Mashud M, Ida R, Saud M (2023) Political discussions lead to political efficacy among students in Indonesia. Asian J Comp Pol 8:184–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/20578911221143674

-

Niemi RG, Craig SC, Mattei F (1991) Measuring internal political efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study. Am Polit Sci Rev 85:1407–1413. https://doi.org/10.2307/1963953

-

Ognyanova K (2022) Contagious politics: tie strength and the spread of political knowledge. Commun Res 49:116–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220924179

-

Valenzuela S, Kim Y, Gil de Zúñiga H (2012) Social networks that matter: exploring the role of political discussion for online political participation. Int J Public Opin Res 24:163–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edr037

-

Valenzuela S, Correa T, de Zúñiga HG (2018) Ties, likes, and tweets: Using strong and weak ties to explain differences in protest participation across Facebook and Twitter use. Pol Commun 35:117–134

-

Velasquez A, LaRose R (2015) Social media for social change: social media political efficacy and activism in student activist groups. J Broadcast Electron Media 59:456–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1054998

-

Weeks BE, Ardèvol-Abreu A, Gil de Zúñiga H (2017) Online influence? Social media use, opinion leadership, and political persuasion. Int J Public Opin Res 29:214–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edv050

-

Zhou Y, Pinkleton BE (2012) Modeling the effects of political information source use and online expression on young adults’ political efficacy. Mass Commun Soc 15(6):813–830

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was done independently by Han Ruixia.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No.H202302681).

Informed consent

All participants completed the survey by clicking on the questionnaire link. Therefore, a clarification of informed consent was provided at the beginning of the questionnaire, stating that all data were used for academic research and did not include personal privacy and that participants could withdraw from completing the survey at any time. Participants clicked on the “Agree” button to complete the informed consent process.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, R. How social media use affects internal political efficacy in China: the mediating effects of social network interaction.

Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1201 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03748-1

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03748-1

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content