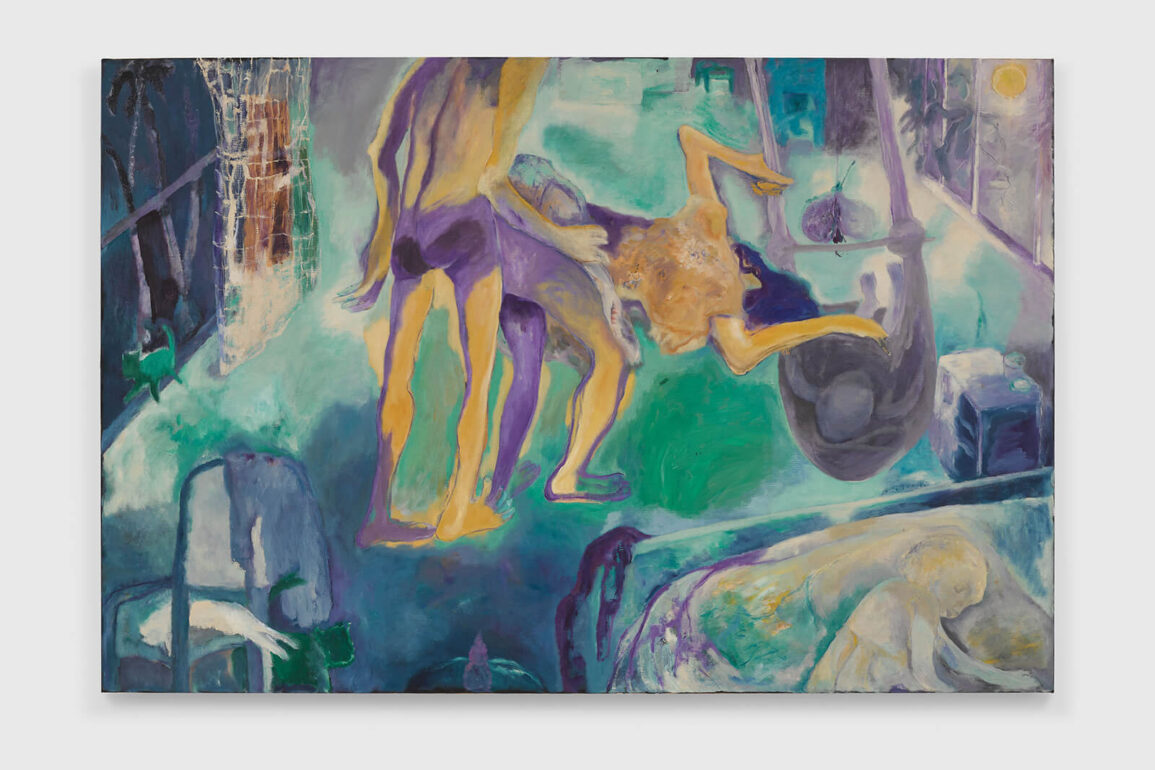

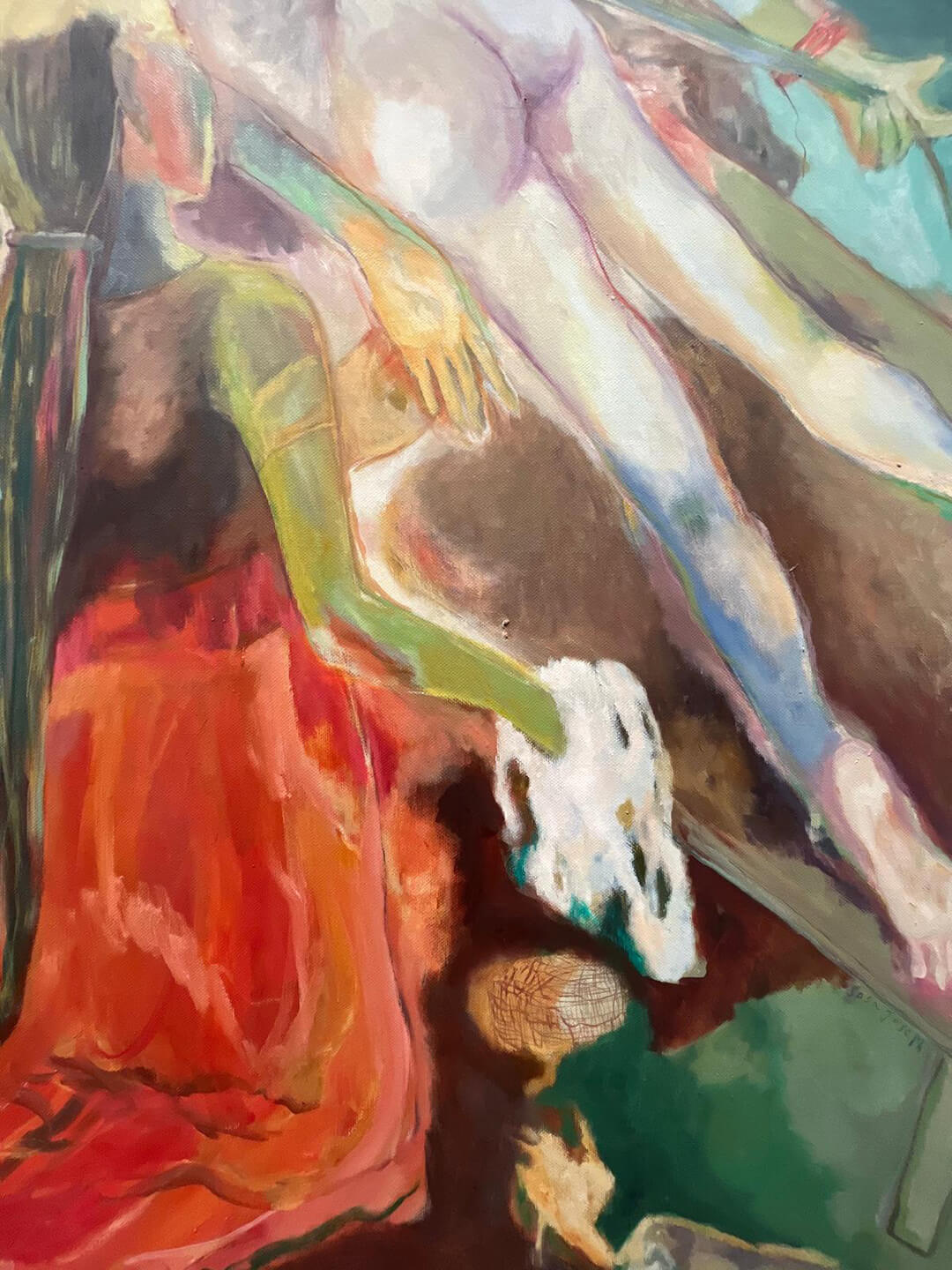

A naked woman lays prostrate across the diagonal of a large canvas by Kerala-born artist Sosa Joseph. The work, Śarada (2023-24), painted with Joseph’s characteristic fluidity and a more sensual palette is among the 14 on view across two floors at David Zwirner gallery in London, in her first European solo exhibition Pennungal: Lives of women and girls. In a talk at the gallery, Joseph explains that the title of the show, Pennungal, is a “not so respectful, dismissive way of addressing women in Malayalam,” her mother tongue, and a word that depending on the tone can connote something like, “oh women, useless creatures”. When the interviewer asks her why she would pick such a term, she says, “It’s quite obvious that I experienced this dismissive attitude from people as an artist… It’s the most natural way I can address all these women.” Each canvas is a testament to this idea — in The cradle (2023-24), a woman is bent over, apparently having sex; in Night of the viper (2024), a woman is being carried away after being bit by the titular viper.

Pennungal, by Joseph’s own description, is her most personal and autobiographical series yet. While Joseph has painted women in their intimate domestic contexts earlier, here, the girls come from a different world. In a 2024 interview for David Zwirner with her partner and most consistent public interlocutor, John Mathews, Joseph says that the “kind of interiority [she is exploring in this series] wasn’t there in earlier works…” Here, painting becomes an occasion to re-discover and give shape to figments from her girlhood, featuring her mother, aunt, friends, mythic women from their stories, and even herself. Generations of women crowd the canvases, occupied by the daily tasks of their lives, amongst their children, livestock, men and the river; Joseph herself appears in Girl in the red blouse (2024) as a young girl looking into her reflection in the water. The paintings address these women that, Joseph says in her talk, live “in” her — the women that have raised her, shaped her and defined the meanings of femininity for her.

Śarada, at first glance, may appear to be a girl being pampered and primped, as part of, perhaps, a pre-wedding ritual. In fact, she is Joseph’s imagining of a teenage girl, her mother’s friend who was found dead in the Pamba river (which surrounds her home village of Parumala in Kerala and forms the backdrop of the paintings in this series); she was presumably killed or died by suicide after becoming pregnant out of wedlock. Joseph tells Mathews, “The important thing is, decades later, Sarada still lay there dead in our daily lives, a constant warning to all of us girls.” When asked about her interest in the dead figure and other afflicted ones, such as that of the woman bitten by a viper, Joseph notes the absurd and inverse logic by which a woman’s physical suffering is presumed to be proof of her moral impurity. Even as her paintings teem with activity and the humdrum of life, the figures that Joseph “finds”—“with one brush stroke,” she says—are haunted by literal and symbolic deaths, morbid anchors for Joseph’s own coming of age as a woman.

In every case, the figures attend to the sharpness, the particular pleasures and everyday humour of Joseph’s ‘pennungal’, alongside the lasting impression of their social affliction and death in Joseph’s psyche.

Conversely, despite the refrain of death and affliction, the paintings are attentive to the surprises of everyday life. As art historian Deepak Ananth writes in his 2017 essay Mattancherry Mix, “There is nothing very precious about Joseph’s treatment of ‘the feminine condition.” We cannot take her to be making universal statements about social oppression. The women and girls around Śarada and throughout the gallery are caught in between gestures — babies climbing onto mothers’ faces, girls splashing water onto buffaloes, or checking their hens’ hindsides, mothers mid-slap. Joseph’s paintings are alive in the “febrility”, as Ananth puts it, the feverishness of brushwork, her indulgent palette and the collage-like narrative space of the paintings that call to mind painters of narrative wit like Bhupen Khakhar. In every case, the figures attend to the sharpness, the particular pleasures and everyday humour of Joseph’s ‘pennungal’, alongside the lasting impression of their social affliction and death in Joseph’s psyche.

Is it then that the 14 paintings at David Zwirner show us who Sosa Joseph really is and who the girls she addresses really are? Many have criticised a way of consuming figurative painting that conflates the figure with the authentic life of a corresponding person in the world. In his detailed review of prominent black figurative painters today, John Baptiste Odour, for example, observes the marketability of “images purporting to provide authentic access to Black life” in the wake of recent liberal moral panics and the rise of figuration’s use as an easy salve to the historical erasure of blackness in Western art history. There is a corresponding danger of making too much of the autobiography, the story and the sheer presence of the “girls and women” of Parumala in Joseph’s paintings.

It is in this context that we must remind ourselves that we don’t and can’t know Sosa Joseph’s girls. Even if they are autobiographical and personal to the painter, neither the paintings nor the painter can be treated as keys to the lives of their subjects. Her painting, Ananth says, “describes and then deviates from description”. Sosa Joseph’s girls only belong to the moment of their discovery on the canvas.

“Sosa Joseph: Pennungal: Lives of women and girls” is on view at David Zwirner, London until September 28, 2024.