Five women artists come together to challenge the traditional art world’s understanding of “emotional” as female

Art, of course, is language, but Mithu Sen is unusually mouthy for a visual artist. Part of her exhibition in Melbourne at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) last year was the word “Unacknowledgement”. Beneath that: “I hereby sincerely declare that I will be withdrawing from charades of inclusion and artifices of language through mOTHERTONGUE.” Charades of inclusion? Artifices of language? And that “sincerely”? Sen enjoys, and employs, ST – serious teasing.

But that is not the end of it. Sen, and the five other women currently exhibiting at Haydens gallery in Melbourne, are defining language by deforming it. Language of gesture, of the eye, the heart, and, of course, the tongue. This tight mixed-media exhibition, under the curatorship of Kathryne Honey, brings the artists together under the title – “banner” is better – Radical Generosity. There’s language again. Political. Here to annoy. Art should delight, shouldn’t it? Possibly.

The commonality of aim is in the diversity and breadth of these women – Sen, Katherine Hattam, Gyun Hur, Ellen Koshland, Jazz Money, Elvis Richardson – of different ages, different experience, different cultures, at different stages in their lives. But this is a collaboration – now incorporated as Who Cares Collective – and it has a beginning elsewhere. An exhibition called Rewriting: the politics of care, first shown at the Melbourne gallery Bus Projects in 2021, included four of the artists here – Sen and Money are new. Honey worked with Sen when she was curating at ACCA.

Tradition – the structure woven through women’s lives – is opaque. Yet it is woven in steel. Tradition is that part of everyday life lived with un-thought, as Sen would say: tasks done as daily routine, the automatic tasks traditionally, universally belonging to women – care, domesticity, labour. And, most critically, that grand concept, the responsibility for a myriad of things felt but unseen. Radical Generosity is about emotional responsibility transcribed, translated and transformed into the dailyness that was relegated – well, demoted – to The Domestic. It has to be said: Women’s Work. Can it be true that the always unadmired domestic is only admirable, only valued, when transcribed by a man. Vermeer? Chardin? Vuillard? Who would dare call them pretty?

The constant and constantly brilliant Germaine Greer, extending questions from Linda Nochlin’s seminal 1971 essay into why there are no great women artists, checked this:

Poverty and disappointment do not afflict the work itself as effectively as do internalized psychological barriers. All women are tortured by contradictory pressure, but none so more than the female artist. The art she is attracted to is the artistic expression of men … she is not likely to have seen much women’s work and less likely to have responded to it. (The Obstacle Race, 1979)

Greer is identifying structural, systemic things. Things have changed, but the art world is glacially slow and way behind the powerhouse world of literature. And it has form. E.H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art (1950), the book that generations of students used as Art Scripture, had no women artists in its first editions. Half the world of art omitted. Katy Hessel’s weighty corrective, The Story of Art without Men (2022), was a response to walking into an art fair of thousands of entries and seeing not one woman artist. That was 2015. Elvis Richardson, an Australian artist and data analyst who has been reporting on women and the art world since 2008 for the rigorous Countess.Report project, details the lethargy with which the art world is embracing not just women artists, but curators and prize-winners. Richardson is fascinated with Gates – not Bill, but those you open and shut. Who is allowed in, who is shut out, who is the gatekeeper. Gates are structural as well as symbolic.

Any art is an enquiry into the self. Life is a process of becoming who you might be, and, as most of us are not and never will be artists, we rely on the few who are to ask: who am I? Why am I here? Why am I like this? We were all taught that using “I” is the greatest sin, but Elena Ferrante, who has a lifetime of thinking about the issues of language, women and politics, believes that “the pure and simple joining of the female ‘I’ to History changes History”. The central question/suggestion, for each of these six women, is how to be eloquent about an interior identity, an urgent and, at times, lonely interior, that is constantly shifting, moving far away from the inherited and mainly external commandments of traditional art. (“Traditional” meaning those old days when the word “emotional” meant female. It was the deepest, most dismissive criticism. QED.) So the word “radical”, trailing a jostle of other words with it – new, disturbing, upsetting, impatient, inquiring, fresh – is suddenly, magnetically zapped into sharp focus. There has been a re-arrangement. Radical is a current allied to emotion and it flows through everything. Particularly the errant “I”.

Radical Generosity takes up the thought across all of these ideas, but in this version Honey wants to focus on public programming. How do you get an audience to stay with the work for a while? To be provoked? How to start conversation between those who might (still) believe art is painting done by those of unique genius (male) hanging on flat walls, sold at high prices to a very few to own and admire, and those who are imagining art into wilder stretches where it does not have to be aligned to some grand (male) philosopher’s idea of beauty?

Honey came up with a practical inspiration: food. A generous table, the surface for any version of hospitality. And talk happens. In a world where concern for the economy – and “product” and “commodity” – presides over the environment, a meal gratis is both radical and generous. And, although a cigar might sometimes just be a cigar, food is never just food. It’s basic. It’s the commonest love-offering. Love me, eat with me, talk with me. A domestic space reworked.

During the exhibition there will be a space to sit down and reflect, with tea, coffee or water. And books! Possibly a biscuit. Cake? Once a week, a table will be set in the centre of the gallery and a meal will be provided by a local restaurant and hosted by one of the exhibiting artists. Sen will be represented by her collaborator Katyayani Sinha. Richardson will open up about Countess.Report. Money might talk about her new book; Hattam and Koshland could invite questions about the urgency of work at a later stage of life. They might ask if it is true that Michelangelo, at 80, said he’d just finished his apprenticeship. Who knows? The point of conversation is in creativity as much as information. The best conversation is when channels of intimacy are opened out, masks are shed, lives are told. The word “emotional” has been gendered, delegated to the world of women, losing status and power. Then – then – this other word “gossip” was established to demean it.

Here’s another iteration: How would anyone know anything of importance without this ill-treated word? Listen. Gossip is the earlier, more casual version of the now high-tech versions of information. Gossip supplies information about the state of the heart and the soul, as well as the body. Thomas Hardy’s Bathsheba was to the point. Responding to a suitor, one of three, she says: “It is difficult for a woman to define her feelings in language which is chiefly made by men to express theirs.” That was 1874. Pick up your chins from the floor.

Rest assured, there will be gossip at the exhibition’s table, so don’t come unprepared. Places will be reserved by ballot. Kathryne Honey has high hopes that “each meal will foster dialogue around themes of care, language, feminism and collectivism”. Gossip. Bring nothing but your tongue and some of your brain; you may cart along every one of your prejudices.

Sen is central to this exhibition. Growing up in West Bengal, where poetry is so richly embroidered in that it is part of the everyday, Sen had a language and visual advantage. Rabindranath Tagore and Satyajit Ray were both born in Bengal, and Sen’s mother is a poet, as is Sen herself. In fact, her art knows few boundaries and often crosses into performance poetry. It’s this bred-in-the-bone ability with language applied, then fused, to her technical abilities as a visual artist that distinguishes her. Language is the thing that enables thoughts, but the tongue allows the thought to fly, or sometimes just nip, from inside your head into the world, into other heads. And the whole chain of suggestion, of dialogue, begins. If the aim of the serious (and seriously teasing) artist is to put their intimate thoughts into the world, then the duty of the viewer, the hearer, is to land those thoughts and personalise them. And then? See what happens. What connects. Art shifts perspective. Raise your eyebrows in incomprehension and move on, but something might have landed. You will be changed and, if you are especially lucky, shaken.

For Ellen Koshland, who will be hosting a Sunday lunch, Sen’s mOTHERTONGUE exhibition at ACCA was startling. “[It] shook my framework of thinking more profoundly than anyone else has in a very long time,” she tells me via email. “She made me see that many of the changes/advances we think we’ve made are tinkering around the edges. Refusing a ‘charade of inclusion’ or identity labels, or art’s role within capitalism are just examples. Her bold act of turning language into gibberish. Yet at the same time of being a person fearlessly deconstructing, she offers the idea of radical generosity … rarely is such a positive counteroffer made at the same time.”

Koshland’s contribution to Radical Generosity is an installation of films called The Landscape of Words. Her videos, projected onto three walls, present a palimpsest of words taken from a recent series of interviews with women “of expertise and authority”. The conclusion sets you back on your heels: “I want to give people a voice. I never thought I would lose my voice.” Expertise and authority say this? That comment can be extended into every aspect of the globe. Nothing is permanent.

The title Radical Generosity landed because of Sen’s ideas. Her concept is that in the unknown zone between artist and spectator there is a pure space that is hospitable to the new. The ideas flow both ways: the artist offers with an open heart, the viewer responds. In the contained space at Haydens, Sen has a contained, new iteration of Unacknowledgement.

There are no portraits here, in the old-world sense of showing the viewer a face, a figure that tells the viewer who the sitter is or was. Oscar Wilde saw that, “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not the sitter.” Feeling? He means emotion. Of course. But here, in this small space, are new portraits of things, usually invisible, generally uncatchable in everyday life – interior lives that have been shaped by exterior shibboleths. Self-portraits, but also un-self-portraits. The sources here are all imagination, emotion, a feathered intelligence. All suggesting the viewer linger before these diverse works. The generosity is in offering an unhidden self to the viewer that might be recognisable. This might be the self called “mawkish” in former days. Mawkishness, in the fresh air of creativity, turns vital and fertile. Who decided autobiography was impolite in every way? Once, in Venice, Sen, who can be as funny as Jane Austen, gave a mock lecture in gibberish and then, with a wide smile, asked if anyone didn’t understand. Recently she made a further point, in Unacknowledgement: “I abandon all imposed identities because I cunt be anything but autobiographical.”

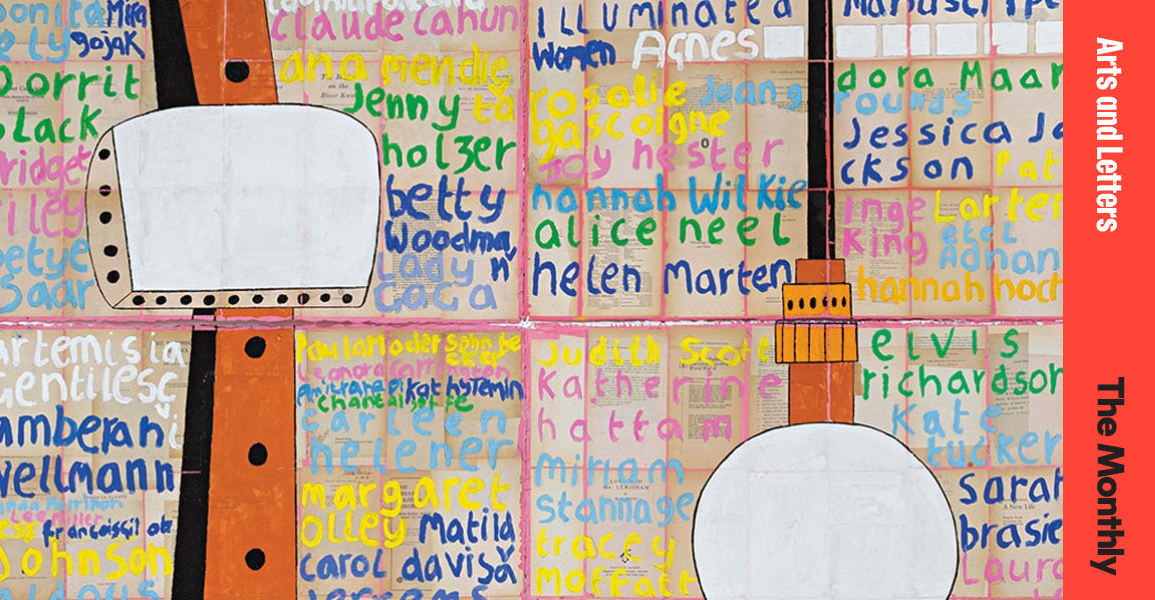

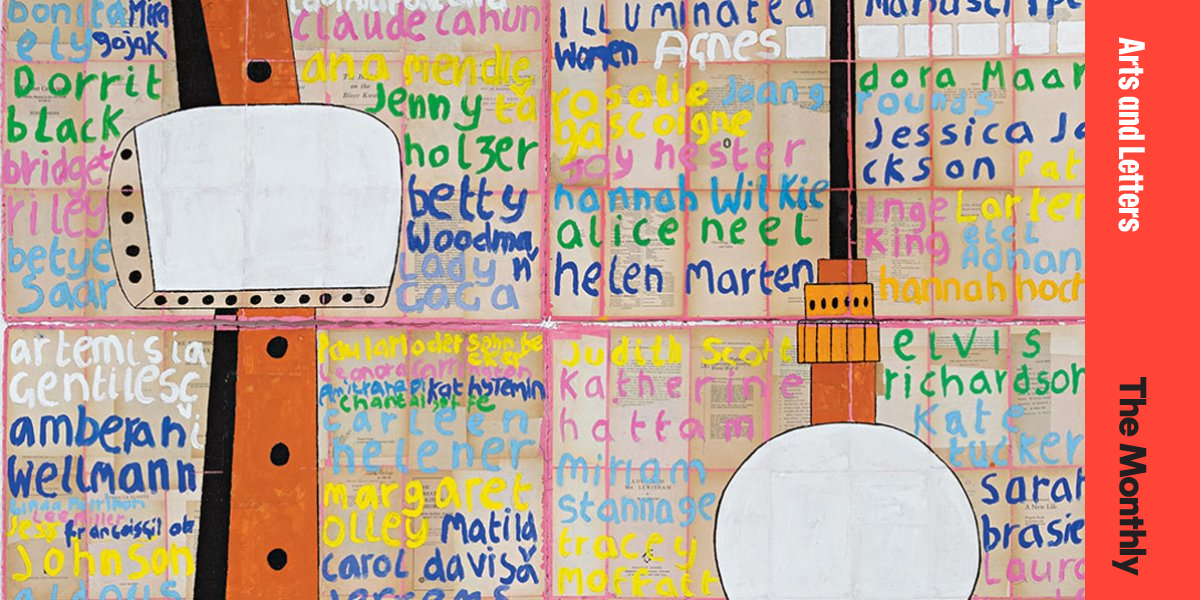

Katherine Hattam’s first language, her mother tongue, is visual. Now in her 70s and aware of the pressures of time, she sees that wide gap between the traditional female persuasion and the severely masculine instruction. Remembering her calamitous falling in love with a work called Pantheon by Canadian-American painter Philip Guston, she realised that the artists in his pantheon – Giotto, Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, Giambattista Tiepolo and Giorgio de Chirico – marvellous and important as they are, were not those she took into the studio. “In my head are female and more contemporary painters,” she tells me. “Louise Bourgeois, Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Rose Wylie.” Here, her paintings, such as Our List No.2, are a joyful swank of gratitude and recognition in the pink, yellow and blues she favours. Hattam is thoughtful about who she is, where she was, and what is important to her. Her work is always recognisable.

Jazz Money, visible more for her writing and poetry, is increasingly immersed in the language and words of her own inner landscape. Indigenous and queer, Money writes that she experiences language in context as “a landscape of words in which women STILL experience not being equal. Not accepted as rightful figures of authority, expertise or power.” Her installation, Bub, Listen up, is a story on two pieces of suspended silk, a “manifesto from the future”. In one, the silk scroll falls to the floor, words collapse into folds so calmly and gracefully the old language would, with un-thought, reach for “ladylike”. Beside the scroll is a smaller piece, a triple mirror image of an individual doing their make-up. On their reverse is a tattoo of a swaggering goanna. “The person in the photograph is my little brother Elijah, a proud trans Wiradjuri brother boy who inspired the text about the future,” she tells me. “The text was written when trying to imagine ‘utopia’, and when I think about the incredible people in Elijah’s community, it gives me hope for the potential for societal change.”

Elvis Richardson’s pieces are all about being an ironic gate fancier. Her famous powder-painted reconfigured domestic gates at the National Gallery of Victoria were a statement and enquiry into access. The gates were in an edible-looking, stickily thick pink. Richardson has a satirical eye about who is behind a gate, who is outside. And the gatekeeper, visible or invisible.

Gyun Hur, working mainly in the American South, is a first-generation migrant to the United States. The idea of “home” – its absence, its presence – preoccupies her. She’s done a series of interviews with artists, over food, but cannot be in Melbourne for this exhibition. For her text-based work, she says, she has “landed on this idea of populating my text through an AI translation app for Korean … We also discussed how this show brings a particular event of racial trauma out of context with time and distance, yet some of the visceral quality of that racial memory remains.”

The world is troubling. And it is fragmenting around us as we speed through, leaving us gaping and anguished, perhaps, but also susceptible to something greater than ourselves as individual. Art is often an ambush that reminds us we are not alone. And it can still encompass The Beautiful; that exact, immense, joyful settling of the imagination into place when prompted by the external. Art in any form is the eternal reminder that we are all part of the evolving collaboration Project Being Human. This project has a specific and urgent task for women. Ferrante clarifies this in a bracing essay about women and language, a project that is at the heart of everything. She writes: “Against the bad language that historically doesn’t provide a welcome for our truth, we have to confuse, fuse our talents, not a line should be lost in the wind. We can do it.”

It echoes the epigraph Hessel chose for her book, attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi in 1649: “I’ll show you what a woman can do.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content