The 14th edition of the ArtRio fair (until 28 September) kicks off in Rio de Janeiro as Brazilian art crests a wave of international recognition, exemplified by Foreigners Everywhere, the main exhibition at the Venice Biennale (until 20 November), organised by the São Paulo curator Adriano Pedrosa.

Brazil’s art market is appreciating the attention: it has doubled over the past decade, to 1% of the global share, according to data published in the annual UBS and Art Basel Art Market report. Yet longstanding roadblocks continue to prevent a lift off: prohibitively high import taxes and a lack of incentives for private cultural philanthropy limit the trade and keep collections locally focused.

What is most noticeably changing within this market is increasing racial diversity. Galleries are now jostling to include more Black and Indigenous artists, so as to better reflect a country in which 56% of the population identifies as non-white—and to meet increasing demand from collectors, both in Brazil and abroad.

This shift can be observed at ArtRio, where many of the 72 exhibitors, almost all of whom are based in Brazil, have recently begun working with non-white artists. Most contemporary art galleries at the fair surveyed by The Art Newspaper are showing at least one Black or Indigenous artist on their stands; in almost every case, those artists were signed to the gallery within the last five years.

It wasn’t until 2010, when Mendes Wood DM began representing Paulo Nazareth, that a living Black artist could be found on the roster of a Brazilian gallery. “That is quite shocking to think about now,” says the gallery’s São Paulo-based director Isadora Dubeux Ganem. “We have a culture of erasing the past in Brazil, but racism is finally no longer being ignored.” Mendes Wood DM has since signed Afro Brazilian artists such as Sonia Gomes and Rosana Paulino, the latter of whom currently has a show of paintings, botanical drawings and installations at the house museum of Eva Klabin in Rio.

Several other Black Brazilian artists have exhibitions taking place in town, like Panmela Castro, whose hyper-feminine show at the Museu de Arte do Rio includes a mirror installation covered in lipstick and graffiti-infused portraits of Black figures. A 2024 painting from this series was sold at ArtRio to a São Paulo collector for $17,000 via Luisa Strina gallery, which has been working with Castro for two years.

While the presence of Black and Indigenous artists in Brazilian institutions predates this wave of commercial representation, only in recent years, as local and global conversations around the legacies of colonialism and slavery have gained traction, has it achieved a critical mass.

The past two editions of the prestigious Bienal de São Paulo have explicitly focused on racism and decolonisation, the most recent of which had an artist list that was 80% non-white. And Panorama, a biennial exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in São Paulo, has played a key role in introducing audiences to artists from the margins, such as No Martins, whose colourful canvases depicting quotidian Afro Brazilian scenes are on show at the fair with Millan gallery.

Perhaps the most radical of these exhibitions is Dos Brasis, an expansive, itinerant group show of 240 Black artists that was launched last year. It is billed as “the most comprehensive exhibition dedicated exclusively to the production of Black artists ever held in the country”. Dos Brasis is helping to familiarise audiences with aesthetic languages within Afro Brazilian discourse outside of the already popular Black figuration, some of which is also on show at ArtRio. Vermelho gallery from São Paulo is showing paintings by André Vargas, who took part in Dos Brasis, which broach the semiotic theories of “Pretoguês” (Black Portuguese), as developed by the writer Léila Gonzalez.

International attention on Black and Indigenous perspectives, particularly in the US, where many Brazilian collectors maintain second homes, is also contributing to more diversity back home. While those onerous import taxes may give Brazil a reputation as an insular market, favourable export laws and the strong presence of Brazilian galleries at US fairs provides its artists access to international collectors and institutions. At the Perez Art Museum in Miami, whose programme has demonstrated sizeable influence in ordaining market success, an upcoming exhibition on Black Brazilian artists, One Becomes Many (12 October-16 April 2026) features rising stars such as Antonio Obà.

In the case of some artists, a mixture of institutional attention, shifts in collecting tastes and social media traction has turbocharged their markets, perhaps none more so than Maxwell Alexandre. Since his 2017 debut at an open submission group show at the Brazilian gallery Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, Alexandre has received solo exhibitions at The Shed in New York, Palais de Tokyo in Paris at David Zwirner gallery in London. The artist hopes to use his growing platform to “have frank discussions about the racism Black people face in Brazil”, he said during a studio tour this week organised by Abact (the Brazilian Association of Contemporary Art Galleries).

Alexandre’s signature medium is oil stick and shoe polish on a light brown craft paper known as “pardo”, which has a double meaning as a racial category in Brazil that was historically used to obscure Blackness. In his latest series he depicts white figures in an exclusive pool club he recently joined. The artist, who grew up in a Rio favela, says he is the pool’s only non-white member.

Thanks to a growing international collector base, Alexandre’s prices are beginning to match those of his Western peers, with pardo works on sale at ArtRio with Millan gallery for $100,000 each. Also at the fair, Luisa Strina is offering a large 2024 painting by the 62-year-old Rio-based painter Arjam Martins, whom it began representing this year. The work, depicting a reclining Black figure in the city’s Parque Lage, is on sale for $120,000.

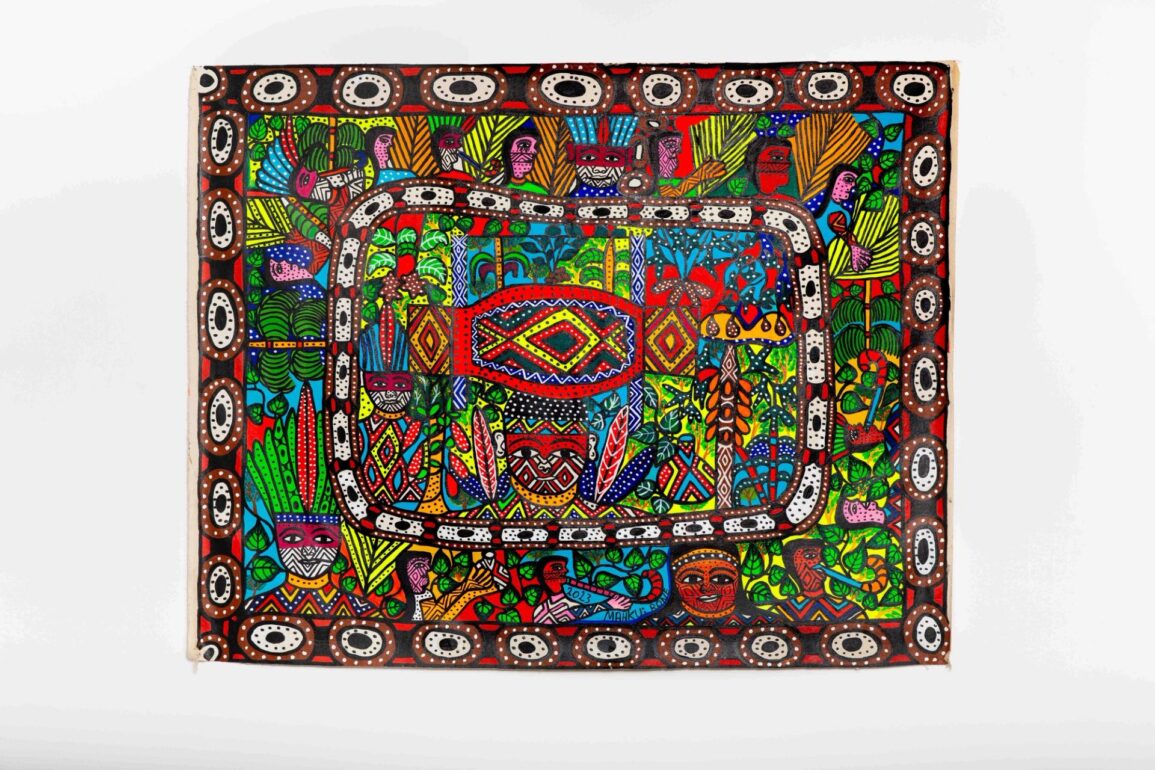

Katxa Nawa (2023) by the Mahku collective

Courtesy of the artists and Carmo Johnson Projects

Indigenous artists are also gaining market visibility thanks to an institutional push. One clear success story of Pedrosa’s Venice Biennale is the artist collective Mahku, from Jordão, who are included in Foreigners Everywhere. Its members use synesthetic abilities to visually translate their chants made during Ayahuasca ceremonies into colourful paintings. The São Paulo gallery Carmo Johnson Projects, which began exhibiting them in 2021, is showing four such works for between $10,000 to $35,000.

“Until a few years ago a gallery in Brazil wouldn’t even think of representing an artist living outside Rio, São Paulo or Minas Gerais. Galleries are now chasing after what they previously ignored,” says Carmo Johnson’s eponymous founder. While “some sophisticated private collectors” appreciate this style of work, Johnson adds, the market is also buoyed by institutions such as the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (Masp), where Pedrosa is the artistic director, and the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil (CCBB), looking to address imbalances in their collections and buy work that reflects the current moment.

One such institution now frequently cited as a buyer of work by Black and Indigenous artists is the Inhotim Institute, the art museum and botanical garden in Minas Gerais. Under new direction, it is making a clear push to diversify its programme and collection. The two temporary exhibitions that are currently showing there are both by Black artists—Nazareth, who is Brazilian, and Grada Kilomba, whose ancestors migrated from West Africa to Portugal. Both are presenting politically charged work explicitly on themes of race, colonialism and slavery.

But even as a more diverse group of artists finally breaks through to Brazil’s established art spaces, their continued marginalisation demonstrates how much work there is left to do. In 2022, Alexandre publicly lambasted Inhotim for a group exhibition of 32 Black artists in which he was included. He wrote on Instagram that he was “embarrassed” by the exhibition’s treatment of Black subject matter and forced the museum to remove his work, stating that white artists are given much more space to exhibit in the museum.

In response, Inhotim stated that in 2025 a pavilion will be inaugurated for the Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga, though this will be the first permanent pavilion for a Black artist in the Brazilian institution’s almost 20 year history.

Installation view of the flight with nostrils breathing, arms wide, messages in the wind at Hoa; the founder of Hoa, Igi Lola Ayedun

Courtesy of Hoa. Aydeun photo: Wallace Domingues

If the presence of Afro Brazilian and Indigenous artists is now more noticeable, equally so is the absence of galleries owned by those groups. The sole player within this lacuna is Hoa, which was founded by the artist Igi Lola Ayedun in 2020 as the first Black-owned gallery in Brazil, which has locations in both São Paulo and London.

Central to Hoa’s mission is redistributing wealth along racial lines (white Brazilians earn 75.7% more than Black Brazilians) and sustainably fostering the careers of its artists from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. It achieves this by providing a “structure of care”, Ayedun says, that goes beyond the traditional gallery model. This includes scholarships, per diems, loans, greater portions of sales going to artists and a demand that collectors invest in artists’ communities.

Ayedun wants Hoa’s programme to move the dialogue beyond a reductive understanding of racial and identity politics and towards something more intellectually complex and stimulating. “You won’t find another version of Bossa Nova here, or work that aligns with a comfortable vision of racial harmony,” she says. Her frustrations at the limits imposed on non-white artists are echoed by Alexandre, who told The Art Newspaper that the expectation for Black artists to pursue figurative painting is a “prison”.

Hoa will from next year transition to a non-profit model and focus on supporting young artists’ careers, as Aydeun has found the cost and logistics of running a gallery too taxing. She expresses disappointment that no Black-owned galleries have emerged in Brazil since Hoa’s founding. She also notes that since the death of Emanoel Araújo, the founder of the Museu Afro Brasil in Sao Paulo, there are virtually no significant Black collectors in Brazil, nor Black museum board members. “Contemporary art culture and lifestyle is based on social segregation,” she says.

The market for a more diverse set of artists has opened up in Brazil, but without long-term support systems that progress could be short-lived if the notoriously mercurial tastes of the art market change again. Mendes Wood DM’s Dubeux Ganem expresses concern of such artists falling victim to “trend cycles” in the future.

- ArtRio, until 29 September, Marina da Glória, Rio de Janeiro