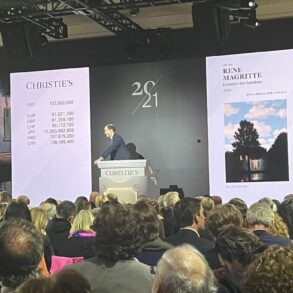

It has been a cruel summer for London’s art market. Emerging art galleries that have closed in the capital include Parafin, Addis, Vitrine and Sundy, most citing the challenging economic landscape for the low-margin businesses of selling contemporary art. London’s June auction season, a long-standing fixture in the art market calendar, felt more of an afterthought this year as Christie’s dropped its evening sale while Sotheby’s and Phillips posted lacklustre results. Marlborough Gallery, a Mayfair stalwart for nearly 80 years, has shut its doors, leaving a vast property for sale.

Other art-market centres are feeling the pinch, even New York, as geopolitical events continue to dampen the all-important mood, which influences art buyers’ willingness to part with their money. Global sales at auction fell 27 per cent in the first half. But for many operating art businesses in the UK, the feeling is that all this could not have come at a worse time. “There are challenges everywhere,” says Camille Houzé, director of Shoreditch’s Nicoletti. “But in London these had already increased because of Brexit — and then you get a global economic crisis on top.”

London’s Frieze art fairs (October 9-13) are doing their bit to inject energy into the city’s art scene. A revamped Frieze London, with a new entrance, more pausing points for visitors and a redesign that gives prominence to emerging art galleries, is part of a mission to “keep London’s pre-eminent position and revitalise the market with a dynamic, vibrant moment”, says Frieze chief executive Simon Fox.

Frieze’s growing list of prizes and acquisition funds, including £150,000 from the fair’s owner Endeavor for the Tate’s collection, support national museums and institutions. A new partnership with London Gallery Weekend and CVAN (Contemporary Visual Arts Network), a national initiative, means that the Frieze fairs support the visits of 30 UK curators (20 from outside London) to the fairs. “An art fair can’t be a success if it doesn’t participate in the ecosystem,” says Eva Langret, Frieze London’s artistic director.

The fair itself, and the city that hosts it, have a position to protect as they compete with rival Art Basel Paris, which opens straight after. Some gallerists are concerned that VIPs might forgo the former to visit the latter, so anything that Frieze can do to persuade them otherwise will serve both the fair and the city.

To this end, Frieze London will this year host a private dinner inside the tent for the first time, which has the added advantage of keeping collectors in the capital at least to the end of the week. “The adjacency [of Frieze and Art Basel Paris] is not unhelpful; people are flying in from America and Asia to be in two of Europe’s cultural capitals,” Fox says. “It’s like Barbie and Oppenheimer opening together,” he half-jokes of the potential multiplier effect.

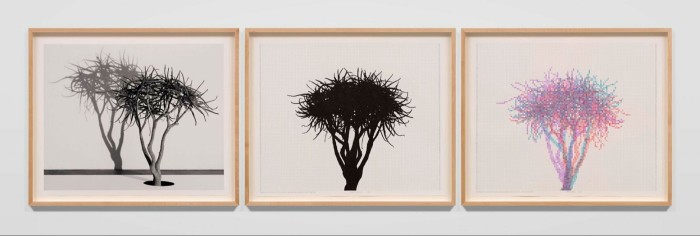

London’s galleries are frank about the challenging times. “The main issue, for emerging galleries like us, is rising overheads,” says gallery founder Oswaldo Nicoletti. These include the costs of shipping, materials and staff. Despite this, he and Houzé took the plunge last month and moved to larger premises in Shoreditch after five years further east. They are managing the move by “reducing costs as much as possible and not hiring”, Houzé says, adding that “we’ve definitely increased our working hours”. At Frieze, Nicoletti will be in the Focus section — now at the front of the fair — with glass-based work by the London-based, Togolese-British artist Divine Southgate-Smith (£4,000-£9,000).

Reining in costs and coming up with creative, often collaborative, solutions seems to be the order of the day. William Lunn, founder of Southwark’s Copperfield, says, “We have seen an uptick in the struggles of colleagues recently and while so far things remain stable for us, we are responding carefully with fewer fairs and a lot more collaborations.” These include hosting a joint show with six other galleries from around the world, themed around female mysticism, which opens this week (October 6-November 23).

Copperfield is also participating for the second time in the Frieze satellite event Minor Attractions, “a fun, grassroots, gallery-led project”, says partner Andrea Maffioli, with work by the British artist Ty Locke that reflects on his dyslexia (£2,000-£8,000, October 8-13). Maffioli says that he welcomes the gradually growing trend of co-representation between the bigger galleries and those such as Copperfield, founded 10 years ago as a project space. “If done well,” he says, “it is good for everyone involved.”

It is not just galleries in emerging art who are joining forces. In London this week mega-outfits Thaddaeus Ropac and Pace Gallery share the showing of two five-part “Combines” works by American artist Robert Longo. The thinking is more practical than financial — they were conceived as a pair and are vast — and “ultimately reflects the way Robert works, exploring every way we see an image . . . Seeing each of these new works in different environments is very much part of this,” Ropac says ($1.5mn each).

London’s Frankie Rossi, who has a booth in Frieze Masters for the first time this year with a solo showing of 12 studio paintings by Frank Auerbach, operates what she describes as a “project-based business”. This means putting on shows when the opportunity is right, rather than committing to a six-weekly programme, and doing plenty of secondary-market dealing while also representing Auerbach and Maggi Hambling. She works in collaboration with Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, where she has office space and whose St James’s gallery she uses for exhibitions that they mount jointly. “We’re a good fit, and it works for us as a business,” she says.

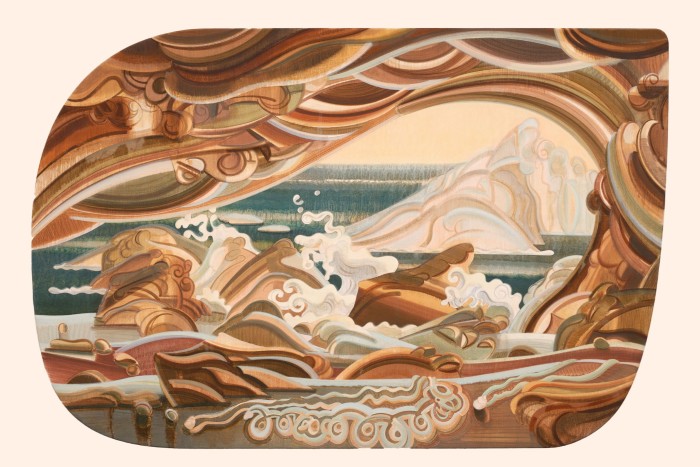

Other galleries are still opening in London. Most significantly, the France-founded powerhouse of Perrotin has confirmed it will open in Mayfair in 2025. Recent other entrants include include Albion Jeune, Cadogan and New York’s Upsilon, while Hauser & Wirth is due to open a flagship space in the former Thomas Goode building in Mayfair next year. Ames Yavuz, a gallery based in Singapore and Sydney, will have its first European outpost in London, having shown in 9 Cork Street (a gallery building also operated by Frieze) earlier this year. “We had so much interest and that set the stage,” says founding director Can Yavuz. He believes that “the essence of London and what it does as a platform for intercultural discourse will never disappear”.

Rossi remains optimistic too: “I know some people who are feeling a bit gloomy and down, and if you have large overheads, it’s a real challenge. But if you have good pictures, they will sell.” London’s galleries, and this week’s art-fair exhibitors from around the world, need her to be right.

October 9-13, frieze.com