In the past five years, there’s been a renaissance in the French art market. Will its strength lead to a decline in prominence for any other European city?

No, absolutely not. I don’t think it’s a threat for any European city. Brexit played an important part in—not necessarily in Paris’s rise but in the new configuration for London. It allowed for a second European capital to emerge. The Parisian scene has built a market over a number of years. Galleries have been very active in getting people to visit. There are private foundations that opened and substantially supported the effort of great public museums. There is a cultural shift in the sense that private and public didn’t use to collaborate as intimately as they do now. It’s also much more international than it used to be and, to be quite frank, more welcoming, less hostile.

There are concerns that the Paris fair might draw people away from the Swiss edition. How can Art Basel ensure that the Paris fair does not compete with its flagship?

Well, I have to say, it’s not like we created a new date on the arts calendar. The dates of FIAC were always the same. And there is certainly a commitment at Art Basel to the city of Basel and the flagship show, which has been operating for 50 years. The goal is to create more contexts, different contexts, and—I don’t want to sound like a marketing manager—more experiences. If you cater to the same audiences globally four times during the year, you want to make sure that you offer them something new and something different each time.

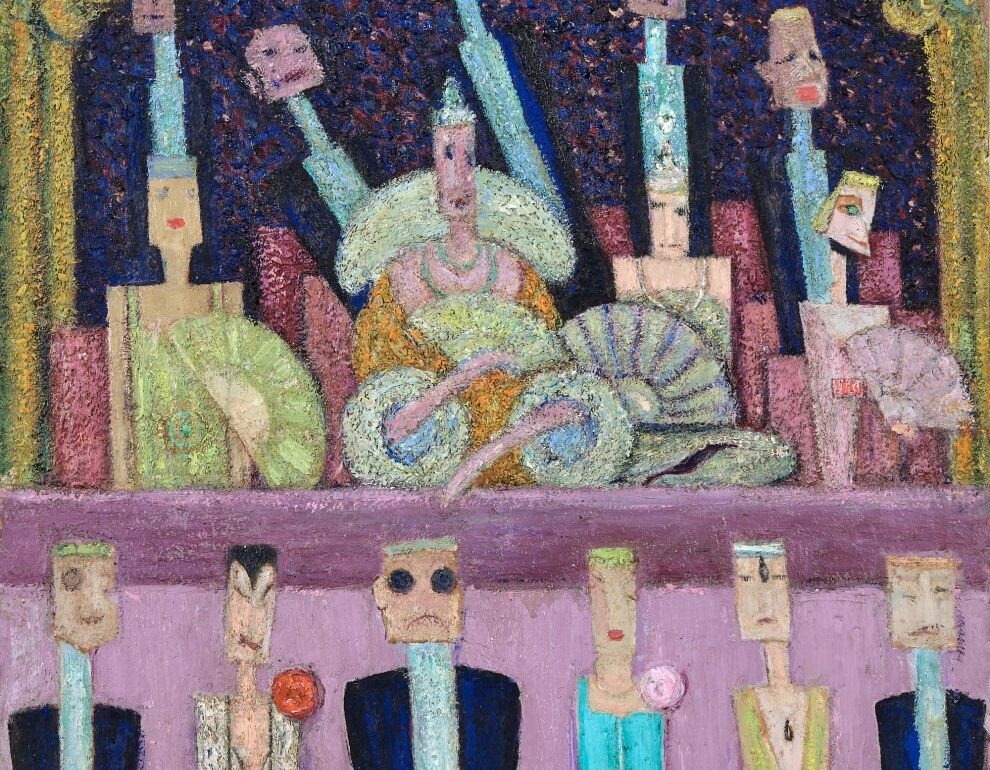

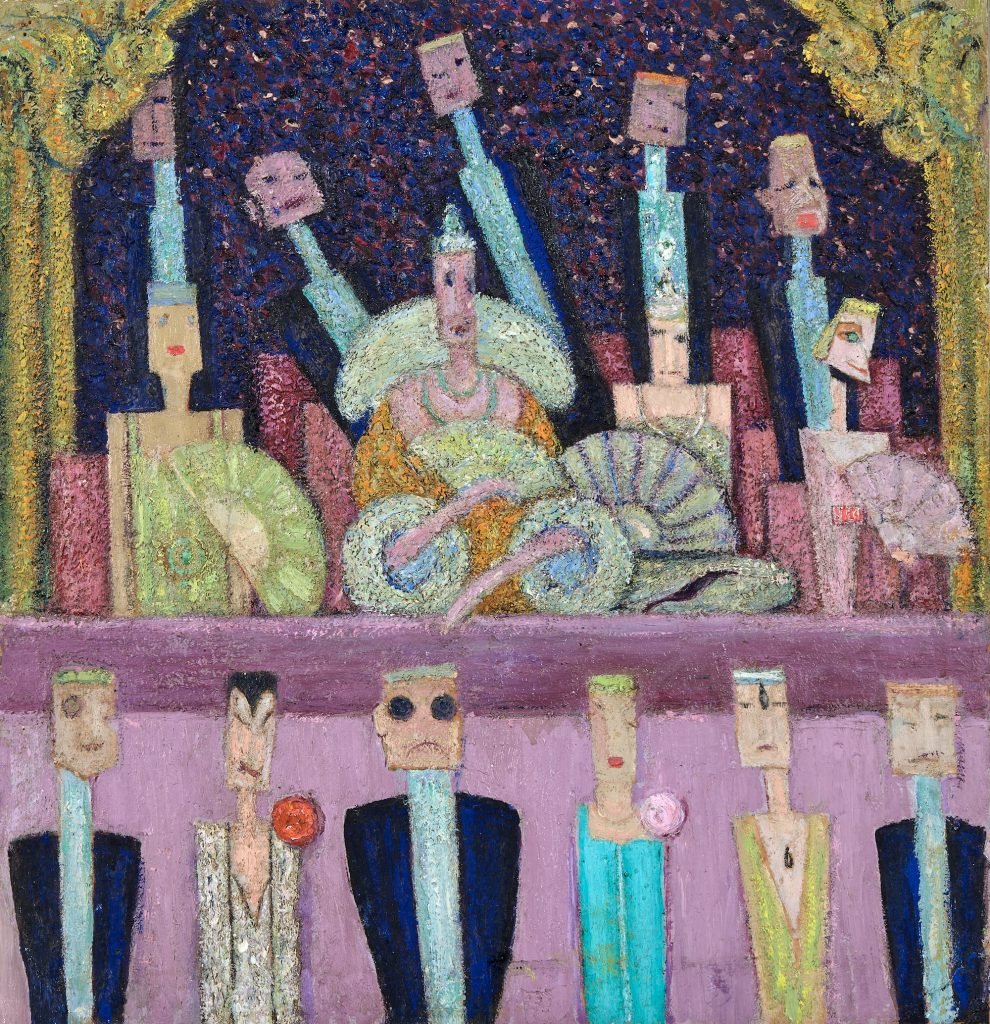

Juliette Roche, Loge de music-hall (ca. 1918). Courtesy Galerie Pauline Pavec.

You came to Art Basel from the Paris Internationale fair, which focuses on young galleries, and in your first year, you doubled the size of the emerging sector. How crucial is this area for the broader art economy?

I think it’s essential. A chain is only as strong as the weakest of its links. Emerging galleries have very fragile economies. They take major risks to highlight what’s being negotiated at the very avant-garde of the art debate. All of the major galleries started as young galleries. It was 14 emerging galleries in 2023. It’s going to go up to 16 this year, and the booths are going to get bigger. But it’s still the same system—the participation is subsidized by the Galeries Lafayette Group. Exhibitors pay half of the bottom price that they would pay in the general sector. Ten galleries are sharing booths this year, which is a record in the fair’s recent history.

Ten galleries are sharing booths this year, which is a record in the fair’s recent history. In light of the current market reset, is the fair being more lenient toward those arrangements?

Well, in Paris, sure. It’s definitely something we’re quite proud of. And that shows how sometimes the lack of space, the scarcity of space, can be perceived as an obstacle when, in fact, it’s also a creative opportunity to collaborate. I’ve had a number of galleries reach out to me and ask if they had more of a chance to make it as single entities or as a collaborative. In certain cases, they had more of a chance, they multiplied their chances, by collaborating. It’s really something that we encourage. Because, of course, the selection committee has the opportunity of getting in two great galleries in one single space. And that’s doing everyone a favor.