Artist Sheila Schwid has lived in the same West Village apartment for more than five decades. If that sounds like a New York miracle, it is. She spent most of those years as a wife and a mother, but now she’s spending her time as the artist she moved in to be in 1970. Now 91 years old, she maintains a studio in the apartment’s expansive lower level that used to house her kids’ bedrooms.

Schwid resides in one of the 384 apartments in the former industrial building-turned-affordable housing community known as Westbeth Artists Housing. More commonly referred to as simply Westbeth and designed by architect Richard Meier, it has occupied a distinctive space in New York City’s cultural landscape since it was conceptualized by Roger Stevens, the first chairman of the National Council of the Arts (later known as the National Endowment for the Arts), and Jacob Kaplan in the late 1960s.

Originally created to be a haven of creative expression and cultural vitality, Westbeth is now a maze of walkers, chairlifts and busy social workers. The New York City landmark qualifies as a naturally occurring retirement community. Many of the building’s original tenants still live there; they’re in their seventies, eighties and nineties and comprise about 60 percent of Westbeth’s current residents.

One of those residents is Schwid. Though she is diminutive in stature, her energy and personal style belie her nonagenarian status—especially her cropped honey-blonde hair, green Keds and coat hanger earrings. Schwid was born in Milwaukee but grew up in Omaha. “I have these memories of being really very, very young and loving to draw and paint, you know, like 5 or 6, and it was the one part of my life that my mother couldn’t correct me on,” she told Observer. Schwid stood out amongst her classmates in art class due to both her talent and gender. She recalled an experience when she was fifteen years old in a figure drawing class. “There were about five guys in the class, and the teacher was a man, and I was the only woman. And women were not really considered anything more than decorative or service providers…whatever they were, they weren’t considered artists.” Schwid recalls all the men in the class taking the best seats, leaving her with the undesirable “three-quarters from the back” for her drawing. Yet, even so, Schwid says that hers was always the best one.

In 1959, Schwid moved from Omaha to New York City with her then-husband, Jay Milder, a prominent abstract painter. The couple mingled with many figures in the avant-garde art scene of the late ‘50s and early ’60s, including Red Grooms and Bob Thompson. Schwid soon became pregnant with the first of the couple’s three children.

SEE ALSO: The World Trade Center Offers Case Studies in Making Space for Artists in Urban Centers

While she was a trained artist, it became clear she was not seen as one in her husband’s eyes. Schwid remembers a night early in the marriage when her husband made clear that he was the only artist in their marriage. She recalled looking at him in amazement: “I thought he knew me as a painter. And he said, ‘Women can’t paint.’”

Schwid said she never internalized the belief that she couldn’t paint, yet she prioritized raising the couple’s three children over pursuing her art—a decision she doesn’t regret. As her children got older, however, she slowly got back into drawing and painting. In 1974, Schwid and Milder divorced, and she began working as an art teacher in the New York City public school system.

Christina Maile, a fellow artist and another original tenant of Westbeth, asserted that Schwid and Milder’s dynamic was not uncommon in their seemingly progressive and bohemian community. “A lot of the wives would have had a background in artistic education and were committed painters,” she told Observer. “But because of general expectations, and because some of them did have kids, they would wind up taking care of the household and leaving their art aside. They still thought of themselves as artists, but they didn’t practice as much because they were committed to their husbands’ careers.”

Similarly, Maile observed another trend, not just within Westbeth but the New York City art scene as a whole: as these women artists got older, either through death or divorce, they became empowered to devote themselves to their art. No longer did they have to manage the fragile egos of their male counterparts. And even if the marriage was happy, there was still the societal expectation that women, regardless of talent, would assume the role of caretaker in a nuclear family.

In Schwid’s case, it was only when she retired from teaching in the ‘90s that she felt she had both the time and financial stability to recommit to painting. “I had to do the thing that is so hard to do when you’re older; I had to start fresh,” she said.

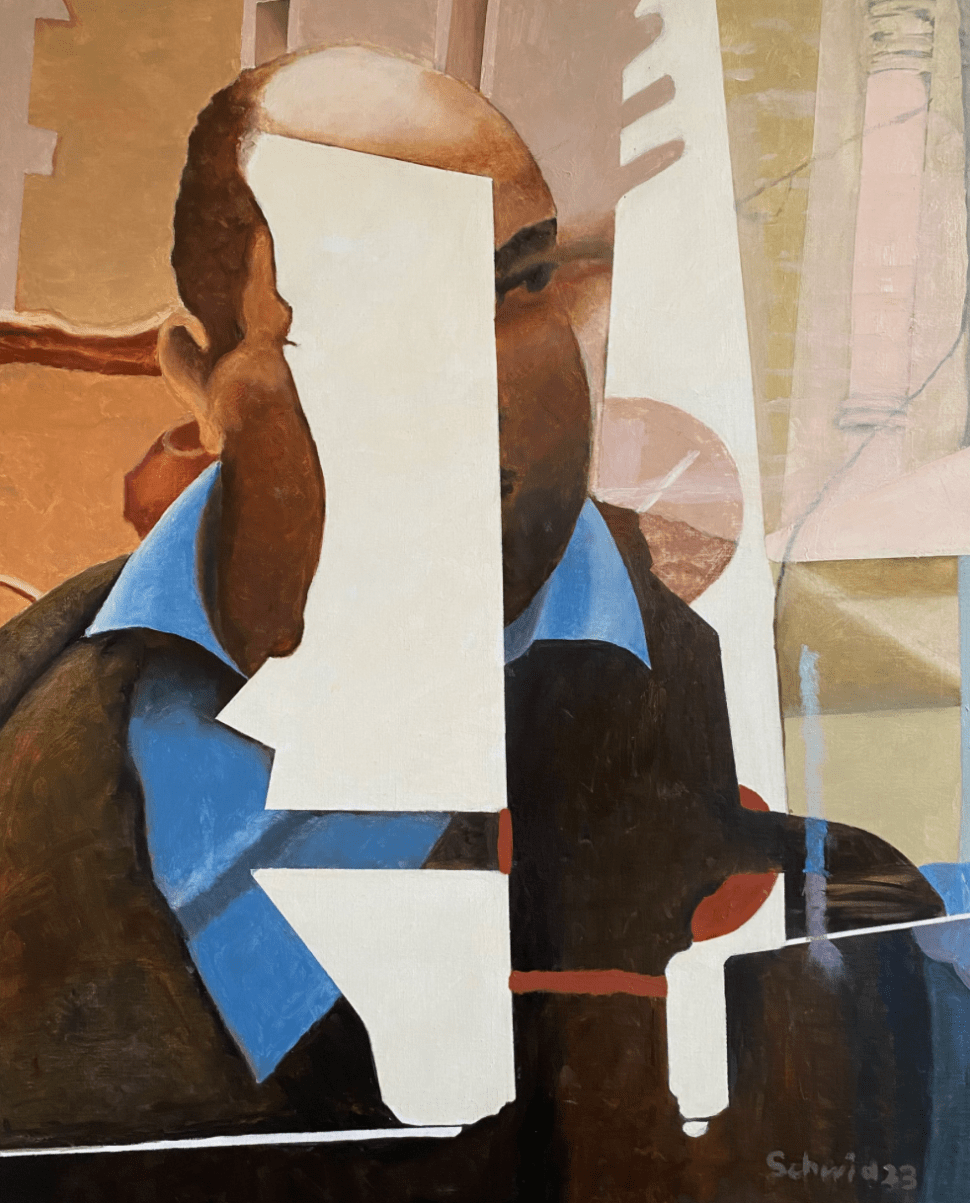

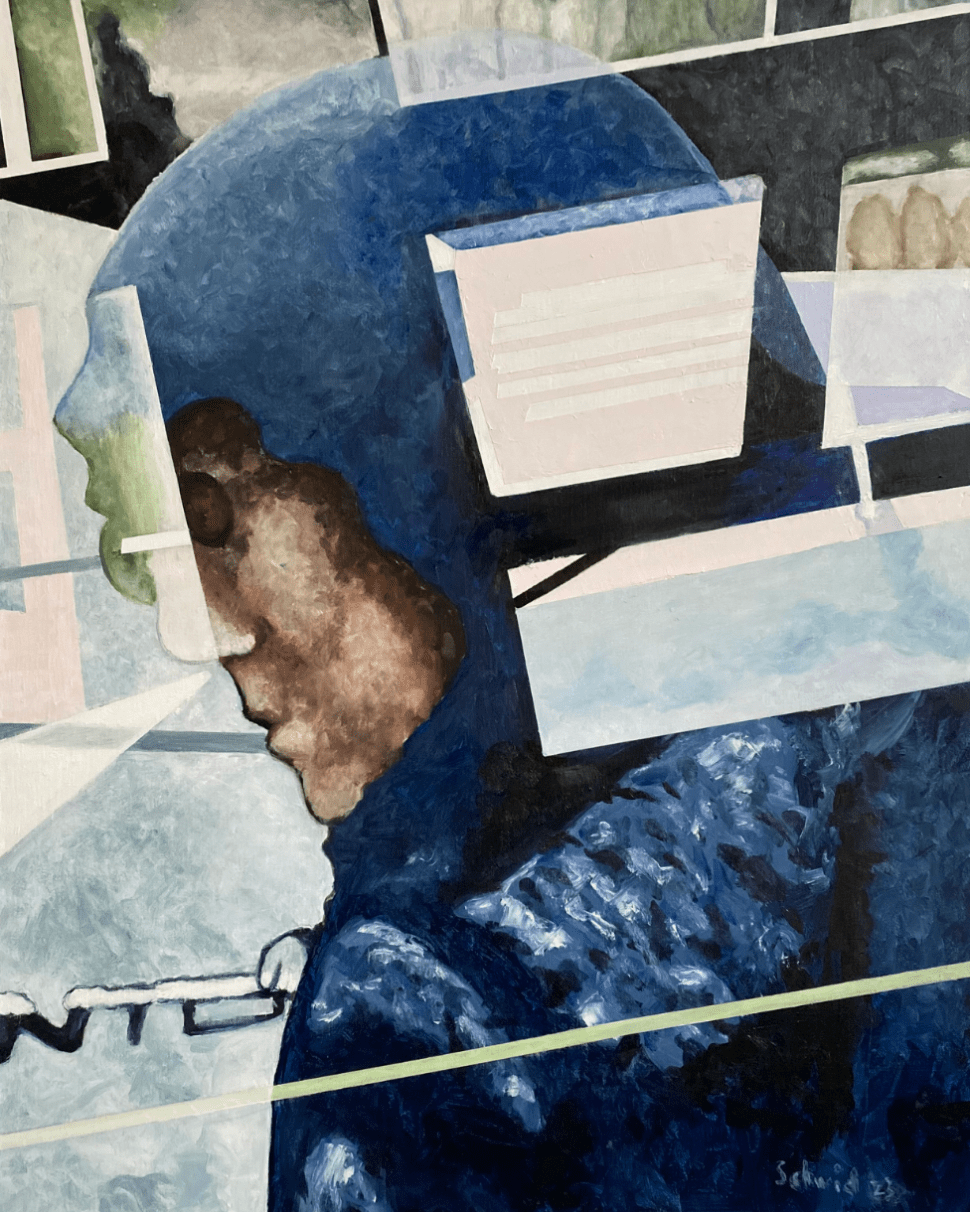

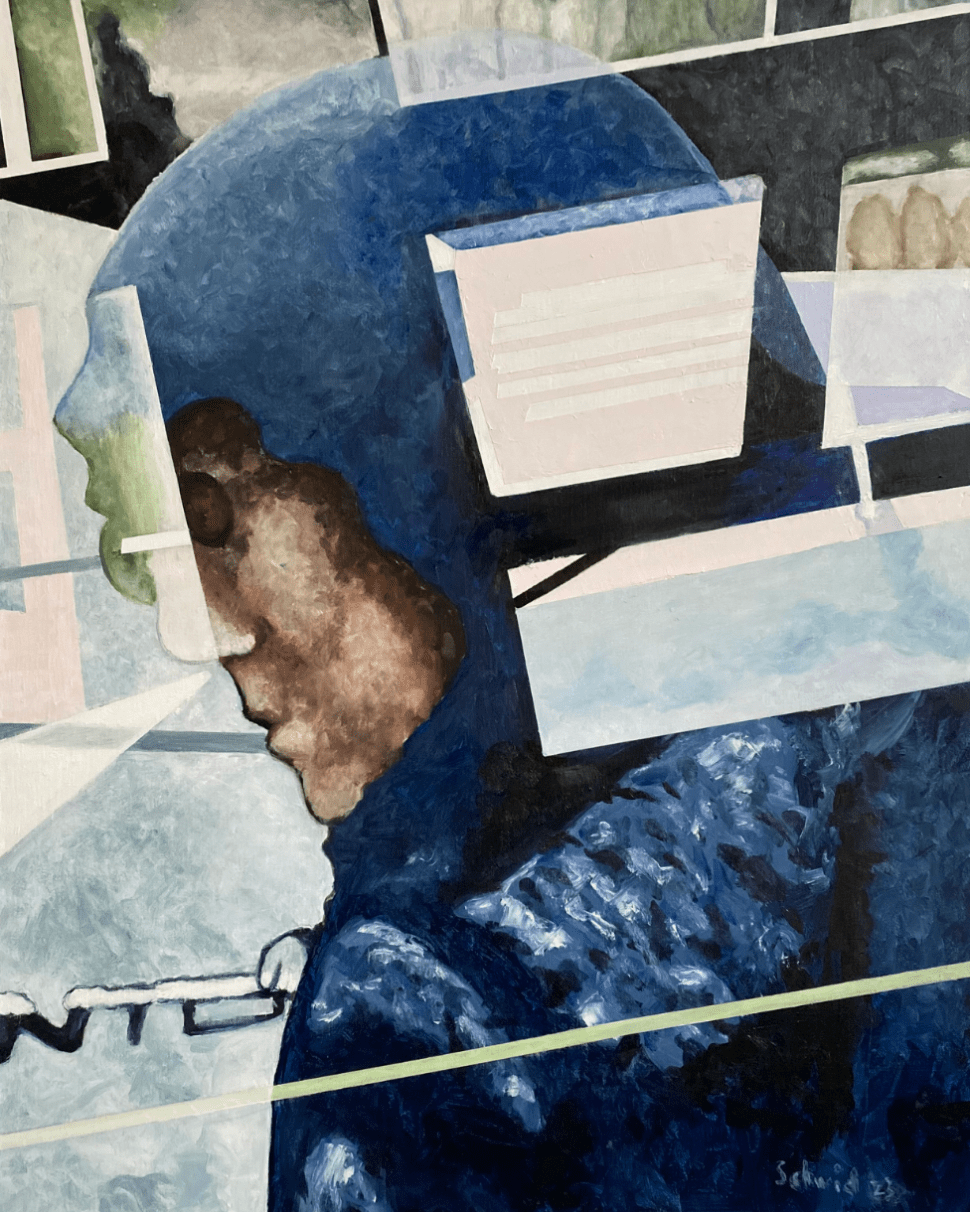

Schwid began a new series of paintings in 2012 titled “Reflections on 14th Street” with paintings created from the photographs she took while riding the 14th Street crosstown bus. She intended only to focus on the busy New Yorkers going about their days, but what she saw was multidimensional, according to her artist statement: “There were reflections, and reflections of reflections. There were strange shapes, cutting off other strange shapes, blank shapes of solid colors, shapes of green leaves of trees I couldn’t see, smoky colors, smoky shapes. People’s heads would be interrupted with windows that looked into the sky or showed us far away traffic.”

The paintings have an illusory quality. In Owed to Age, the focus is on the profile of an elderly woman, her face shrouded by a navy hood. “I’m very empathic with her because she’s probably my age,” said Schwid. But the woman is bisected by the various reflections coming from the window, ranging in tones from light pink to deep green and blue-gray. The paintings are meant to be complicated and confusing, just like our lives. Each time you look, you find something new. The series has been shown at the Carter Burden Gallery and the Westbeth Gallery in Westbeth Artists Housing.

This past April, Schwid received a $25,000 grant from the Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation. The award recognizes artists who have spent their lives committed to art. She plans to continue her “Reflections on 14th Street” series and host open houses later this year.

What does it feel like to receive this type of recognition now, in her tenth decade? “I know when I look at my number, I know I don’t have that much time left. And I know that I’m on borrowed time. It scared me when I was 90—I was afraid. My kids asked me why, and I said, ‘I feel like I’m taking extra time that I’m not really allowed to have.’” Still, Schwid has no plans to stop painting—or taking photos on the crosstown bus.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content