Art

Emily Steer

Oct 14, 2024 4:29PM

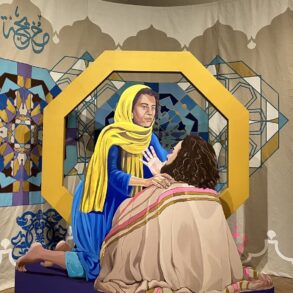

Miranda Forrester Two mothers, one scar, 2023. Courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary.

The myth of Leda and the Swan has been reimagined countless times. The story follows Zeus’s transformation into a bird, in order to ravish the Spartan queen Leda. Traditional artworks by revered painters such as Leonardo da Vinci, Peter Paul Rubens, and Antonio da Correggio present a seductive embrace between a nude Leda and the Greek god in swan form. Such depictions portray a straightforward sexual encounter, avoiding the violent and devious undertones of Zeus concealing his identity.

Subsequent modern artists visualized the barbaric aspects of the story. Cy Twombly’s 1962 painting named after the myth is an abstract, bloody tangle of sharp pencil strokes and red lines, suggestive of a swan’s turbulent feathers flapping, rather than its serene grace. Willem de Kooning’s 1989 bronze sculpture series based on the myth also evokes a more twisted view, with bodily forms emerging from a dense mass of material.

Today, a host of contemporary women artists are revisiting the tale’s gendered dynamics, presenting Zeus’s actions as clearly non-consensual, or delving into lesser discussed narrative. Crucially, these works embrace the complexity of the original tale. Some highlight how cruel behavior can be concealed beneath an appealing appearance, while others invite a more open attitude towards motherhood.

Barbara Walker, End of the Affair, 2023. © Barbara Walker. Photo by Chris Keenan. Courtesy of the artist and Cristea Roberts Gallery, London.

Ariane Hughes, ‘(a 2 year) Mistake’, 2013. Courtesy of the artist

Advertisement

Turner Prize nominee Barbara Walker explores the dissonance of Leda’s experience in her work End of the Affair (2023), which was shown (along with several artists discussed here) as part of Victoria Miro’s group exhibition “LEDA and the SWAN: a myth of creation and destruction” last winter. Currently, the work is on view in Walker’s solo exhibition “Being Here,” which runs through January 26th at the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester, England. The work is an intricate pencil drawing showing the artist with arms folded, staring down the viewer. The fragile skeleton of a swan sits behind her. Everything is monochrome except the top of her dress, which is drenched in red. The work subverts classical depictions of Leda as submissive and offers a contemporary reading on toxic relationships.

“He no longer has any power over her,” Walker wrote in a description of the piece. “Before, he was a beautiful creature, now he is just an ossified specimen.” She explained that the myth has a personal resonance for her: “Leda is me thinking about a past relationship. I made a conscious decision to put myself in the frame. But it’s also about relationships in general—who we are and what we possess and desire.” The work challenges the presumed whiteness in Greek mythology, with Walker, who is Black, placing herself center stage. Instead of portraying the proud white plumage of the swan, its pale bones visualize his decaying state.

Ariane Hughes, ‘Me, Myself & I’, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

Swans also recur in artist Ariane Hughes’s paintings, which take inspiration from Zeus’s violent, duplicitous actions in bird form. Her works are visually appealing, a sumptuous mix of soft pink and black, the swan’s feathers rendered with a pearlescent sheen. “What interests me most about the original myth is that the sinister is concealed behind innocence, and the way that beauty can serve as a façade,” she said in an interview with Artsy.

Two of Hughes’s swan paintings are included in “Post-Human VI,” a pop-up exhibition at Marylebone Square. Duality, she explained, is a crucial part of the process. “Recently I have been trying to emulate how the French academic painters built a surface,” she said, referring to the 19th-century group of artists who prioritized a soft realism in their work. “Whilst my subject matter can be challenging, it is rendered with a deftness of touch that’s both alluring and misleading.”

Heather B. Swann’s 2021 exhibition “Leda and the Swan” at Tarrawarra Museum of Art in Healesville, Australia, addressed the tale’s moral ambiguity. An installation of paintings and sculptures included three presentations of the myth. One sculpture ominously portrayed a black swan behind a smaller nude body; another featured a mass of 19th-century glass eyes staring out from dark quilted silk.

Heather B. Swann, installation view of Leda and the Swan, 2021 in “Leda and the Swan” at TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and STATION, Melbourne and Sydney.

Swann was interested in the idea of pathos, the “deep melancholy” that is embedded in objects. In this case, the works themselves embodied the pain of the myth. While the exhibition made visible the horrific undertones of the original story, it also invited open contemplation. “There are powerful physical and historical and social tensions in the Leda myth,” Swann said when the show opened. “I’ve created this exhibition as a place of stillness, a place for thinking.”

Artist Saskia Colwell has taken a more direct approach to the violence of Zeus’s attack. Her charcoal works Her Eyes Were Full of Feathers, Lick of the Lips, and Slither (all works 2023) evoke his physical brutality. In one, a splayed bird’s foot is shown crushing human flesh underneath it. In another, a phallic swan’s neck glides across a bare pair of breasts. “I like to zoom in close so as to almost abstract the body, forcing the viewer to look twice to understand what they are seeing,” the artist wrote of these works on her Instagram.

Artists have also been inspired by the consequences of the myth—in particular, the children that resulted from the union. Following Zeus’s rape of Leda, she lays eggs containing two sets of twins. In one telling, one of these eggs had actually come from Nemesis, who was also impregnated by Zeus. She delivers the egg to Leda, who raises all four children as her own.

Saskia Colwell, Her Eyes were Full of Feathers, 2023. Photo by Jack Hems. Courtesy of the Artist.

Miranda Forrester, Leda and Nemesis children, 2023. Courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary.

British painter Miranda Forrester took inspiration from this side of the story for her painting Leda and Nemesis’ Children (2023), which was recently shown as part of Tiwani Contemporary’s group exhibition “In the Blood.” In the oil-and-gloss-on-polycarbonate work, a woman who could be read as either from the original story is surrounded by four young figures.

Forrester explores the ambiguous parenthood in the myth to connect with her own experience as a non-birthing mother. “I wanted to remove Zeus from the conversation and instead focus on Leda, her sexuality and sensuality, and display this in the image with her four children,” Forrester said in an interview with Artsy. “It spoke to my personal experience of not being genetically related to my daughter,” she said, noting that some types of motherhood are currently seen as “inferior” in our society. “These ideas of motherhood actively harm all women…I feel passionately about communicating these feelings and truths within my paintings.”

By challenging Zeus’s barbarity, excused or denied in many art historical pieces, artists today are rethinking this traditional story. Presenting a more nuanced understanding of romance, sexual violence, and motherhood, these artists show that a Greek myth may be steeped in history, but can still evoke the dynamics of contemporary relationships and family structures.

Emily Steer