The artist Kathryn Andrews has launched the Judith Center, a women-centred organisation focused on promoting projects related to gender, race and sexual identity. The centre will open to the public as a 500 sq. ft space on the 12th floor of the LA Mart building Downtown in January, where the artist’s own studio is also located.

The idea for the centre began to take shape during the 2016 US presidential race, when Donald J. Trump and Hillary Clinton were competing for office. “I was struck by the intensity of the dialogue around gender at that time and how normalised it was in the culture to disrespect female politicians,” Andrews tells The Art Newspaper. “Not just with Clinton in particular, but it seemed that all women attempting to enter positions of power faced threats and violence.”

In 2020, Andrews premiered the ongoing work Women for President at the DePaul Art Museum in Chicago, which chronicles the history of women running for president in the US from 1872 onward. The project features the faces of male presidents superimposed with the names of women who have run. During this election cycle, an iteration of the project has been on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (until 17 November).

“I’ve looked at many histories of violence and have reflected on what it means to be a woman. The field of art is intensely sexist—it runs rampant in the auction market, galleries and museum collections and exhibitions,” Andrews says. “How can we affect change in the art world from within? How can we make a case for the fact that women are equal when, in the US, we haven’t even had a female president?”

Martine Syms, SHE MAD: The Non-Hero, 2024 Courtesy of The Judith Center

The name of the centre derives from the ancient story of Judith and Holofernes, which artists throughout history have taken as a subject. The famous 1612-13 version by Artemisia Gentileschi, for example, has come to be seen as a reflection on her rape and the subsequent trial, which had “more to do with her rapist having defiled her family name, or of protecting the patriarchal line”, Andrews says.

“It’s one early example of art being used to exact some kind of justice when the system has failed women,” she adds. “Similarly, with the centre we want to create art-focused activities that are a vehicle for social justice when the system has failed.”

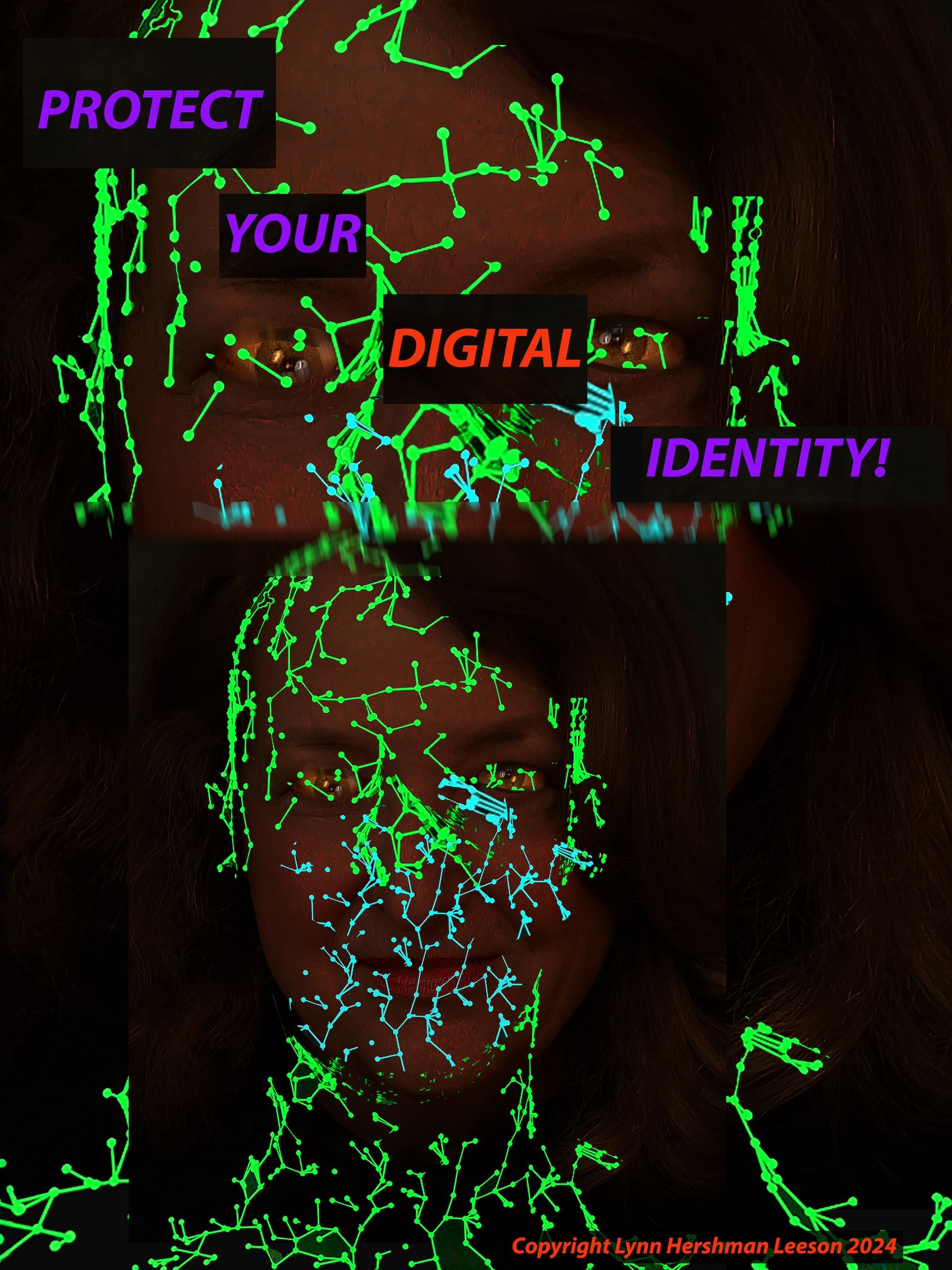

Much of the centre’s programming focuses on the history of political posters. Its first major initiative is the Poster Project, a five-year project that began at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University with the exhibition The Judith Center Poster Project [Phase 1]: Freedom in the Automation Age(until 16 March 2025). It features images by artists including Lynn Hershman Leeson, Martine Syms and others critiquing gender-related topics. The project will travel to other US museums in the coming years.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, OWN YOUR IDENTITY, 2024 Courtesy of The Judith Center

In October, the centre launched an initiative called Poetry X, a series of workshops and readings. Under this initiative, the centre will hold conversations and projects related to women in political office, voting patterns and other democratic issues. Another cornerstone of the space’s programming is the Judith Center Oral History Project, an archive of audio recordings related to the work of women artists.

Visitors to the most recent edition of the Felix Art Fair in February 2024 may have seen the centre’s project Women in Print. A collaboration with the Center for the Study of Political Graphics (a Los Angeles-based organisation that houses around 90,000 political posters from all the world, dating back to the 1800s), the project featured 20 posters and nine commissions.

Andrews emphasises that the centre will be inclusive and welcome “conversations around questions from multiple perspectives simultaneously”. “Gender issues are a problem that intensely impacts all of us, which is why it’s important that men and non-binary people be a part of this as well,” she says. “From that mix, we begin to understand the nature of this problem and how deeply it is embedded in our systems.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content