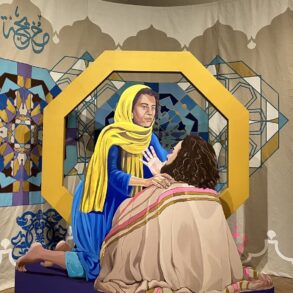

It’s hard to imagine now, but once upon a time, most big museums in New York—the Guggenheim, MoMA, the Whitney—were run by women.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, for example, named her longtime assistant and advisor Juliana Force as the director of the Whitney when she opened it in 1929. Solomon R. Guggenheim named his advisor, the artist Hilla Rebay, as director of his Museum of Non-Objective Painting in 1939 (and she later selected Frank Lloyd Wright to design its future home as the Guggenheim on Fifth Avenue). Meanwhile, trio of friends Lillie P. Bliss, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, and Mary Quinn Sullivan worked together to found MoMA in the late 1920s.

This fall, the museum is spotlighting the overlooked, often incorrectly recorded history of its creation with both a new book, Inventing the Modern: Untold Stories of the Women Who Shaped The Museum of Modern Art, and an exhibition centering the work of one of those early founders, “Lillie P. Bliss and the Birth of the Modern,” opening Nov. 17.

CULTURED spoke with the show’s curators, Ann Temkin and Romy Silver-Kohn, about the enormous contribution made by the little-known trustee, her unusual bargain with the museum upon her death, and why all those esteemed institutions had women at the top then—and so few do now.

CULTURED: Why did you decide to publish this book now?

Ann Temkin: I think it’s part of a large body of books that have been appearing over the last few years, and that will keep appearing, that have to do with historians realizing that so much of the history we’ve learned as students or as professionals was very incomplete—in large part because that history tended to be written by men. It overlooked, diminished, and excluded enormous contributions made on the part of women. Whether you’re talking about business or science or art, you name it. We feel we’re very much part of a community of historians who are looking back through modern history, but also centuries before and just realizing it’s not that women weren’t doing these things, it’s just that their legacy was not really recognized because subsequent historians did not record it. They weren’t looking for what women were doing—they were looking for what men had been doing.

Romy Silver-Kohn: It’s also important to mention that it’s very much in the spirit of, and in conversation with, what the museum has been doing with the galleries over the last more than a decade. We’re trying to make sure that the collection galleries reflect the same idea, that it’s not the same old history of art that was written in part by the people here, but that so many more voices get to come to the fore and so many more people get represented, so the history becomes much more complex.

We often come back to this article we found that was published in Life magazine around the 50th anniversary of MoMA, in 1970. The headline was “Three ladies and the Genius who Launched the Museum.” And the sexism in that is so clear, right? It could never be the ladies who are the geniuses, but that has been how the story has been told for so long. The women get mentioned, but they’re really not a part of the story. You just move quickly to the story of [MoMA’s first director] Alfred Barr and how he basically created the Museum of Modern Art. We really wanted to correct the record on that, which is that many, many people were shaping this museum—and honestly, very many of them were women.

CULTURED: You point out in the book that the founders and directors of some of the biggest New York art institutions, including the Guggenheim, Whitney, and MoMA were women. Why do you think that was possible then—perhaps even more possible than it is today?

Temkin: Part of the answer is remembering that these were not prestigious enterprises or powerful institutions then. So something like the Whitney, which not only had Gertrude Whitney as the founder, but Juliana Force as the first director, were experimental. You didn’t see powerful women or directors at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which at that point was already a big, prestigious, powerful establishment. But at these places, and they’re all basically born around then—the Whitney, the MoMA, the Guggenheim—they were startups.

CULTURED: The exhibition features 40 works from the collection Bliss bequeathed to the museum upon her death, including those by Paul Cézanne, Odilon Redon, Georges-Pierre Seurat, and Pablo Picasso. Why did the museum decide to focus on her collection, as opposed to the other 13 women highlighted in the book?

Temkin: In thinking about which of the 14 women we might want to spotlight via an exhibition, it obviously came down to the trustees, and we realized this year is the 90th anniversary of Bliss’s collection, which really became the beginnings of MoMA’s collection. It was a nice way to honor that anniversary by doing the first show devoted to Lillie since the 1934 show at MoMA when the gift was made official.

CULTURED: How many of the works from that original show will you put on view now?

Silver-Kohn: All of the works that are in our show were also in that show, except [Vincent Van Gogh’s] Starry Night. That’s a whole different story, which we can tell you. But that show had more because one other aspect of Lillie’s will, which was so unique at the time, was that it allowed the museum to sell works from her collection in order to acquire new work over time. Some of the works that were in her collection all those years ago have since been deaccessioned in order to bring other works in, including Starry Night.

Temkin: In addition to what you see in the space of this exhibition, we give you a QR code that takes you to all of the pictures that are now hanging in the collection galleries elsewhere in the building that were bought over the subsequent decades using Lillie’s pictures as the way to fund those purchases. It’s a kind of treasure hunt through the galleries for things that were by artists who weren’t even all in Lillie’s time—but because she knew that the museum needed to be a growing thing, she permitted us to exchange everything in her collection as it seemed prudent in order to update MoMA’s collection.

CULTURED: Isn’t it pretty rare for a collector to allow institutions that kind of freedom with their collections?

Temkin: There’s a lot of variation, but I think what stands out with Lillie is the lack of egotism, and the foresight she had in 1931 that for a collection going to MoMA it would not necessarily be in the best interest of the museum to retain each and every work. Here’s this place that’s only been in existence two years, has almost no collection, just a few scattered gifts here and there, but absolutely no formal program of how you store things, how you conserve things, how you catalog things, and she took the leap of saying that’s the kind of place MoMA should become. That MoMA, from day one, was a place whose heart and soul was acquiring and collecting and displaying and preserving modern artworks.

When we opened, we were more an organization that presented temporary exhibitions without that other part as our heart and soul. That’s why she made that farsighted move of saying, “I’m not just going to bequeath you these things when I die,” which would have meant everything here would have been acquired in 1931, but [attached to it a stipulation that said] “I’m going to make you prove, over the course of three years, that you understand the costs that such a transformation really incurs, and you have to prove that you can raise that money so that you can responsibly care for not only my pictures, but everything going forward like a grownup museum has to do.”

CULTURED: It really shows her commitment to experimentation, and the knowledge that art would always be changing.

Temkin: That’s exactly right. Rather than to kind of immortalize her exact own taste.

CULTURED: What works did you sell to acquire Starry Night?

Temkin: It was two paintings by Cézanne and one by Toulouse-Lautrec.

CULTURED: She gave a lot of Cézanne, right?

Temkin: Yes, she had a very large collection of Cézanne, especially for the time. He was one of the first modern artists she really fell for in terms of connecting with their work. By the way, Starry Night was the second piece we bought by an exchange from Bliss, in 1941. In 1939, we used an Edgar Degas painting to buy Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. So that was two immediate giant steps forward in 1939 and 1941, enabled by the Bliss exchange opportunity.

CULTURED: What does Bliss’s collection tell you about her taste or philosophy as a collector?

Temkin: It’s for certain that today it looks to us like classics of modernism. For example, the first show that MoMA ever did opened in 1929, and it was a show of four artists—Cézanne, Van Gogh, Seurat, and Gauguin. Today, those are old masters in the sense of modern art. But at that time, those would have been radical artists. It would have still been controversial work, unfamiliar to most people. So one of the tricks to get across in our show is that we as people in 2024 come in and say, “Oh, here are all these landmark modern classics.” But when she was buying them they did not have that status.

Silver-Kohn: They were reviled by a lot of people. One of the things we’ve come to understand about Lillie is that she wasn’t just a forward-thinking collector, but also an advocate for modern art in so many ways—she was able to push the United States in its acceptance of this type of work. She not only lent her collection to a variety of very early exhibitions of Modern art in the United States, but even advocated for museums to stage exhibitions of modern art.

CULTURED: Do you have a sense of why so many women, in particular, were drawn to modern art?

Silver-Kohn: It’s hard to say generally. One thing about Bliss that we’ve been thinking about is that she had a pretty constrained life. She lived her whole life with her parents until they passed away. She never married, she never left home, she played the role of a very dutiful daughter. She ran the household, so very early on in her life she took on a lot of responsibilities and she continued to live under the paradigm her parents set out for her—so this is all to say, I think she found a certain amount of independence and freedom in her art collecting and in the process of learning and discovering modern art that wasn’t as available to her in the rest of her personal life.

Temkin: Her mother did not let her hang anything but Cézannes in their house. When you enter the exhibition, you’re going to see a big, fantastic [wallpaper] blow up of Bliss’s apartment. She was only able to build that apartment for herself—it was a triplex—after her mom died, which means she was able to live there for just three years before she passed. She moved into that house around the same time MoMA was founded, so for all of two decades, she’s this activist for modern art and not allowed to hang it in her own house.