In a recent act of defiance, Ahoo (Mahla) Daryaei, a doctoral student in French Literature at Azad University’s Science and Research branch in Tehran, protested the oppressive enforcement of mandatory hijab in Iran by stripping down to her underwear on campus. She had reportedly been harassed by members of the university’s Basij paramilitary group — a faction of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard — who allegedly tore her clothing for not fully complying with the Islamic dress code. In response, Daryaei removed her remaining clothes, sat on campus grounds, and walked around in her underwear, leaving passersby stunned. She was soon arrested and reportedly taken to a psychiatric hospital, a frequent strategy used by the regime against protesters. Footage of Daryaei’s bold gesture quickly spread across social media under the hashtag #GirlofScienceAndResearch (دختر_علوم_و_تحقیقات#), sparking both national and international dialogue about women’s rights in Iran.

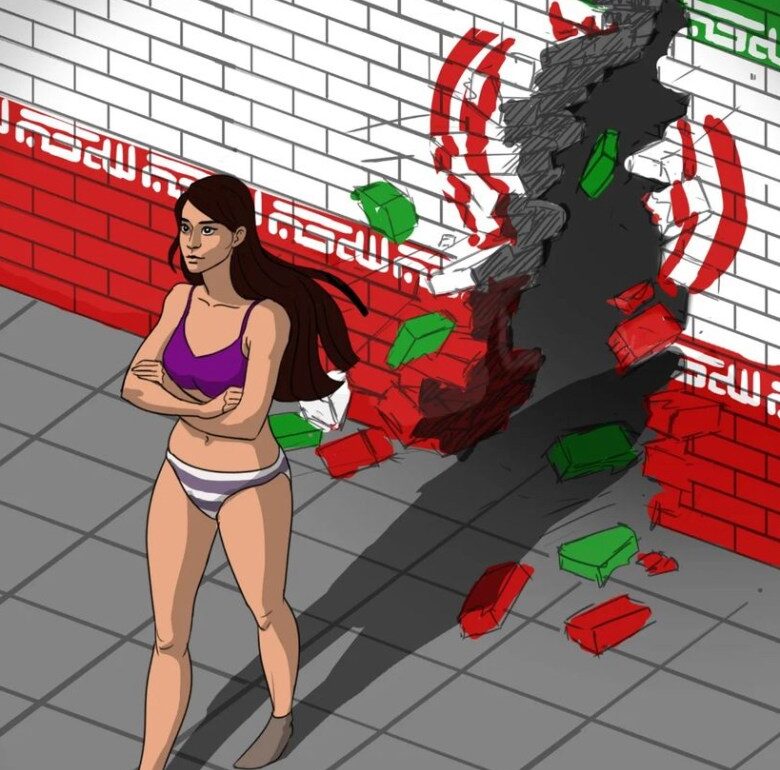

The hashtag galvanized a flood of artistic representations of Daryaei’s defiance, depicting her in powerful symbolic scenarios: towering over a city teeming with morality police, standing defiantly before a tank, or breaking through a wall emblazoned with the Islamic Republic’s flag. These visual portrayals, which have dominated social media and even appeared in graffiti form, parallel other iconic symbols of resistance, such as the “Tank Man” photograph taken by Stuart Franklin during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 in China.

This was not an isolated protest. Iranian women have long resisted the compulsory hijab, using nonverbal acts to defy the state’s strict dress codes. This movement began years ago in quieter, subtler forms: women wearing their headscarves loosely, discarding their veils, and expressing dissent through subtle but powerful body language. In 2017, a woman named Vida Movahed took this resistance to the public stage. Standing on a utility box on Tehran’s busy Enghelab (Revolution) Street, she waved a white headscarf on a stick — a striking image that captured the essence of Iran’s feminist struggle and inspired countless others, later known as the “Girls of Revolution Street.” Since then, women have performed creative acts of defiance with their scarves, twirling them, casting them into the wind, and even burning them. Daryaei’s act of stripping to her underwear continues this trend. One illustration poignantly captures this connection, depicting Daryaei running toward a hurdle labeled “freedom” on a track, as she receives the iconic white scarf on a stick as a baton from Movahed. These acts embody a larger struggle for bodily autonomy, freedom, and the right to self-expression.

What we are witnessing is a unique form of feminist expression that I call Gestural Feminism, where the body itself becomes the tool and language of resistance. This is not merely an act of protest by ordinary citizens but also a marker of protest and feminist art in Iran. In 2011, a poignant act of remembrance unfolded in Tehran. Each afternoon, a group of women, dressed entirely in bold red, gathered at a busy intersection, marking the spot with their steady presence. This daily ritual paid tribute to a woman who, before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, had famously stood at that very location, also dressed in red, reportedly awaiting a man she loved, a display of affection in a city where such public expressions are now forbidden. Despite facing jeers from passersby, these women returned every day for about a month, embodying a powerful act of resistance and homage through their presence.

In 2017, dancer and filmmaker Tanin Torabi performed a slow-motion dance through Tehran’s traditional Tajrish Bazaar, capturing the scene in a one-shot film. Her subtle yet unconventional bodily movements leaving passersby stunned. That same year, artist Nastaran Safaei created a powerful video, “High Heels,” where she walked the entire length of Vali Asr (formerly Pahlavi) Street in her favorite high heels. Captured on a hidden GoPro, the video reveals the public’s misogynistic reactions to her act: the stares, puzzled looks, verbal harassment, and sexually explicit catcalls.

In my recent book, Women, Art, Freedom: Artists and Street Politics in Iran, I explore how artists use their craft to challenge the regime. During the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising of fall 2022 to spring 2023, sparked by the death of Mahsa (Zhina) Amini at the hands of Iran’s morality police after she wore her hijab incorrectly, artist Nasrin Shahbeygi reclaimed public space by rolling through the streets of Mashhad, while artist Zohreh Solati stood in busy intersections around Tehran without a hijab, dressed in an outfit made of square-shaped mirror pieces. This dynamic expression of Gestural Feminism highlights the resilience and creative spirit of Iran’s artistic community in times of resistance.

Conventional concepts of the “gestural” in art focus on expressive brushstrokes and the artist’s physical engagement with the canvas. But in Iran, gestures go beyond paint; they involve standing, walking, and bodily presence as tools of political expression. In these acts, the body becomes both art and defiance, embodying silent yet profound statements against repression. Beyond mere protest, they reclaim autonomy over the body and its movements, often in environments where such freedoms are rigorously policed. These gestures, symbolic yet deeply rooted in reality, reshape public understanding of feminism in Iran, expanding it from verbal discourse to a realm of nonverbal, corporeal expression.

This ripple effect resonates not only in the exchanges between grassroots protest and performance art but also in the visual artworks that have emerged in solidarity with Daryaei and other women protesters. Artists and activists worldwide have envisioned her image, standing proudly in her underwear, often looming over figures symbolizing regime authorities.

Shifting between spontaneous protests and deliberate performance art, Gestural Feminism in Iran is more than mere defiance; it is a language, an art form, and a movement. This gestural language redefines activism, seamlessly blending it into art and demonstrating that sometimes the most powerful statements need no words.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content