” data-image-caption=”

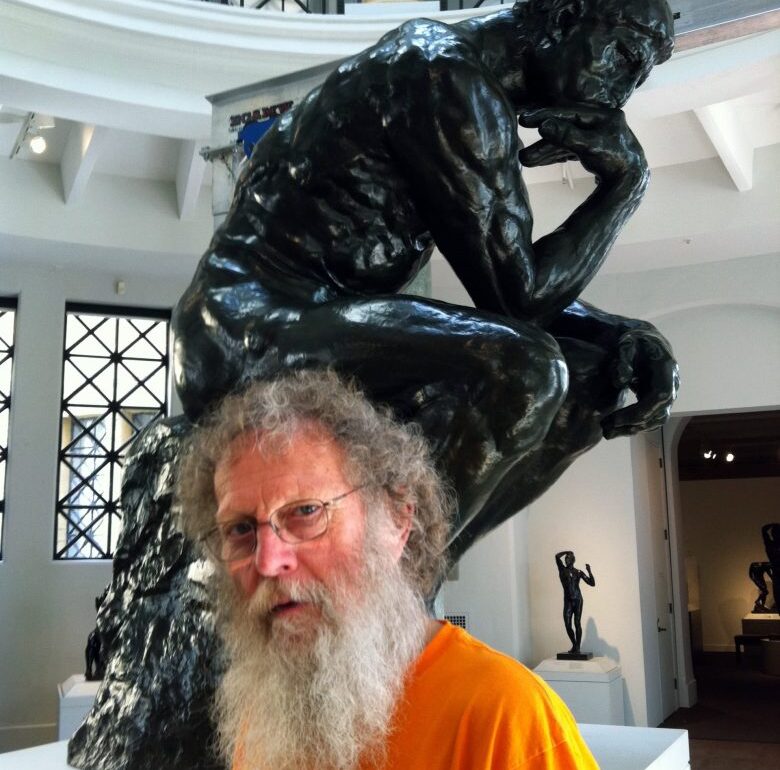

Scott Atthowe installing Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture Crouching Spider on the Embarcadero, San Francisco, 2007. Courtesy: Atthowe Fine Art Services

” data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?fit=360%2C278&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?fit=780%2C602&ssl=1″ src=”https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=780%2C602&ssl=1″ alt class=”wp-image-528420″ srcset=”https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?w=2048&ssl=1 2048w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=360%2C278&ssl=1 360w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=194%2C150&ssl=1 194w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=768%2C593&ssl=1 768w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=1536%2C1185&ssl=1 1536w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=1200%2C926&ssl=1 1200w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=583%2C450&ssl=1 583w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=1568%2C1210&ssl=1 1568w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=2000%2C1543&ssl=1 2000w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=400%2C309&ssl=1 400w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?resize=706%2C545&ssl=1 706w, https://i0.wp.com/newspack-berkeleyside-cityside.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/20241122-200749.webp?w=370&ssl=1 370w” sizes=”(max-width: 780px) 100vw, 780px”>

Editors’ note: This obituary first appeared on the Other Minds website and has been republished with permission.

When the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge opened in 1936, the way of life of Northern Californians changed irrevocably. For artist Scott Atthowe, this signal event would provide a bridge to the invention of a completely new occupation, destined to modernize the work of museums, galleries, and artists worldwide.

Atthowe died peacefully at his home in Point Reyes Station, California, overlooking Tomales Bay, on Oct. 31, 2024. The cause of death was complications of Lewy body dementia. He was 80. His beloved wife and partner of 44 years, Patricia Thomas, and his sister Sherill Ladwig were at his bedside.

Born in Berkeley on Oct. 15, 1944, Atthowe grew up in the Berkeley Hills in the home his parents built in 1942. He spent much of his childhood roaming Tilden Park, which was practically in his backyard. He was an entrepreneur from an early age, loaning his lunch money to his Hillside Elementary School classmates. He attended Garfield Junior High and Berkeley High School. In the 1960s Scott and a friend had a small business dealing in Packard car parts.

As the founder of Atthowe Fine Art Services in Oakland, Atthowe parlayed an art moving business that he started in 1970 in Sacramento with a single three-axel truck into a thriving multi-faceted business, founded on the principle that the business of moving art was best left to artists who had direct experience handling the materials they would transport.

His international business now caters to a broad array of museums, artists, and collectors for whom he provides storage, fine art and large-scale sculpture installation, packing, crating, and transport.

Former SFMOMA Director Neil Benezra commented, “The Bay Area art world has lost one of its key pillars with the passing of Scott Atthowe. One could always have complete confidence in the standards with which Scott and his team worked. At SFMOMA we often undertook unorthodox and challenging installations and Scott was always up to the adventures we created. He was an absolute treasure and he will be missed by all who cared about art in our community.”

Atthowe’s crowning accomplishment was one of those unorthodox projects — the years-long process of removing the giant Diego Rivera fresco mural, Pan-American Unity, from San Francisco City College and installing it in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2020–21. Its 10 plaster panels, measuring 22 by 74 feet, weighed over 60,000 pounds. This monumental task, including strategizing with experts in Mexico City and the closure of miles of San Francisco city streets, was documented in a public television special by PBS station KQED in San Francisco.

Locally, Atthowe has been entrusted with the very largest and most complex art moving projects. When the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art relocated from Van Ness to its new headquarters on Third Street, Atthowe Fine Art shipped everything in the museum to storage in South San Francisco, then to the new building on Third Street for its grand opening. This process also was repeated for the de Young Museum, the Palace of the Legion of Honor Museum, the Pacific Film Archive, the Bancroft Library Papyrus Collection, portions of the Asian Art Museum, and the rare books of the Law Library (formerly Boalt Hall) at the University of California.

Atthowe Fine Art also performed multiple fine art installations at the San Francisco International Airport and the Olafur Eliasson Seeing spheres (2019) in front the Chase Center, home of the Golden State Warriors basketball team.

The large and notorious Beat-era painting by Jay DeFeo, The Rose, eight inches thick in some parts and weighing a full ton was painstakingly removed from the San Francisco Art Institute, conserved by numerous experts, then moved to the Whitney Museum in New York. Atthowe was called upon several times to hang the piece and eventually taught the Whitney staff how to do it themselves. Video documentation shows the tall energetic hippy, as always resplendent with his signature long beard and smiling eyes, directing the high wire act of craning the painting out of a window at the Art Institute.

Historically, the Atthowe family had been at the center of the transportation business. Scott’s grandfather John Atthowe, a tugboat captain, began running barges in 1928 to transport materials to and from land masses now connected by the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and Golden Gate Bridge. When those structures opened in 1936 and 1937 respectively, barges no longer were essential, so he turned his attention to the trucks that had been used to deliver to and pick up from the barges. That business, East Bay Drayage, was passed on to Scott’s father Charles Atthowe who continued to run the company until his retirement in the 1960s.

In the early 1970s, Scott, by then a working artist in need of moving his own large-scale sculptures in metal, concrete, and laminated wood from one point to another, purchased the trucking authority from his father and began also assisting others. Having grown up around commercial vehicles, drivers, and mechanics, he naturally was suited to fulfilling his colleagues’ transport needs, even for their most unwieldy large works, then newly in fashion among modernist sculptors and painters.

Up until that time, art shipping had been handled mostly by household goods movers, blanket-wrapped or crated, and moved like furniture. Atthowe felt that the added weight and expense of crating could be mitigated by soft-packing in plastic, cardboard, bubble-wrap, or even packing blankets for shipment in specialized art trucks driven by pairs of trained art handlers (often artists themselves). He was able to offer a higher quality service with reasonable rates to museums and galleries nationally. Atthowe also initiated cross-country trips to East Coast institutions and became known and trusted for the reliability of his services. Another innovation was his use of temperature-controlled trucks to achieve optimum preservation of painted canvases and other delicate objects.

In addition, Atthowe offered temperature-controlled, high security storage for artists and collectors and museums with more art than wall space. He wisely invested in large industrial buildings in Oakland where he could rent out storage space to customers to preserve their collections of fine art. This service provided his company with a steady income stream to offset the inevitable fluctuations of requests for moving services. Rather than rent buildings to accommodate his clients’ storage needs, he purchased them, expanding from one structure to five as he acquired more clients. This ensured financial stability for the company’s growing operation, now serving museums nationally and providing the transportation as well as expert installation of large works, including public sculptures.

Atthowe was never one to turn down a complicated project. His remarkable ingenuity, with an architect’s sense of spatial relationships and an artist’s sensitivity to the value and fragility of art, led him to solve uniquely puzzling assignments. In 2010, when the People’s Republic of China lent the United States a 15-ton statue of copper and steel measuring 26 feet in height, the work arrived disassembled into four shipping crates with no real instructions. Atthowe and his team reassembled Three Heads and Six Arms which went on display in San Francisco’s Civic Center for over a year. Among hundreds of projects here and abroad, he installed large sculptures by Bruce Nauman at Fort Mason, Mark di Suvero at Crissy Field, Bruce Beasley in Germany, and a monumental spider by Louise Bourgeois on the Embarcadero. Atthowe also installed the European tour of the California Sculpture Show 1984–85 in France, Germany, Norway, and the United Kingdom, featuring works by Robert Arneson, Fletcher Benton, Robert Hudson, Manuel Neri, Sam Richardson, and DeWain Valentine, among others.

Scott Charles Atthowe was the son of Jean and Charles Atthowe. He began studying architecture, then earned a bachelor’s in art at California State University, Hayward, and a master’s in art at Sacramento State University. His interest in visual art originally was encouraged by his mother, who was an accomplished textile artist. He then planned to become a sculptor, working in large scale metal and concrete.

“Getting into this business was sort of a sideline,” he said. “The idea was to work part-time at this and also work in the studio.” In reality, Atthowe found his fullest expression in the management and growth of his business. He hired working artists almost exclusively, allowing them flexible schedules so they still could devote part of the week to their studio work. Their natural aptitude for handling artwork and creative problem solving made them a good fit for the business, and Atthowe provided personal training in the trade and gave every one of them high-quality health care coverage, instilling a loyalty that is reflected in the long tenures of their service. Furthermore, men and women were paid equally. Before it came time for Atthowe to retire in 2021, he worked for two years with his devoted staff to pass on the business to them as a co-operative, employee-owned venture.

Loyalty similarly has been a feature of the company’s clients. They have come to trust their most important projects to Atthowe because of an outstanding record of success. “This is a business where accidents maybe might happen, but mistakes are not allowed,” said Atthowe. “We take our time and always work in teams. You have to be 100 percent on.”

Atthowe was highly regarded for his great generosity, loaning funds even to competing businesses to support the infrastructure of art world businesses. When KPFA Radio in Berkeley needed to offload 4,000 tapes of music programs and offered them to the San Francisco music nonprofit Other Minds, co-founder Charles Amirkhanian, formerly the Music Director at KPFA, called his longtime listening fan Atthowe to appeal for help. Not only would it be a major moving job, there was no place to store the tapes safely. Atthowe quickly organized the boxing and transportation of the tapes to a suitable storage room in his own facility. The Hewlett Foundation stepped up to pay the movers for the packing and transportation. And Atthowe selflessly donated the storage space rent-free to preserve these and other materials for Other Minds. Most of the recordings now have been digitized and are available to the public free of charge at the Other Minds website.

Scott and his wife, Patricia Thomas, a visual artist, lived in Oakland above the business for many years before developing their West Marin home and art studios of 20 years. They have been avid supporters of the art community, including SFMOMA, the Oakland Museum of California, and Oakland’s Creative Growth Art Center.

Atthowe was also devoted to environmental issues and very early on ran his business with an array of solar panels, electric vehicles, recycling, and renewable sources of energy. His belief was also personal and he regularly donated funds to causes for a healthy environment, world peace, civil liberties and civil rights.

Atthowe is much-admired for his innovations in combining art and business. His integrity, kindness, and savvy will be sorely missed by his colleagues and acquaintances throughout the world, as attested to by condolences to the company staff that have arrived from Germany, Switzerland, Japan, Italy, India, and around the U.S. In the words of fine art conservator Anne Rosenthal, “Scott Atthowe’s death represents the passing of an era.”

His first marriage, to Janice Barbary with whom he started his company, ended in divorce. Scott Atthowe is survived by his wife Patricia Thomas, his sister Sherill Ladwig, his sister-in-law Charlene Kramer, and cousin Helen Atthowe.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content