She’s the first woman, and the first Canadian, to present a solo exhibit of her work at the Library of Congress, and two of her paintings can be found at Washington’s National Portrait Gallery. You’d recognize Anita Kunz’s often satirical works from the covers of Sports Illustrated, Time, Rolling Stone and the New York Times magazines as well the designs on more than 50 book jackets. In 2018, the Canadian Post honored her decades of wide-ranging illustration with a postage stamp, and the artist has also received Queen Elizabeth’s Jubilee Medal of Honor.

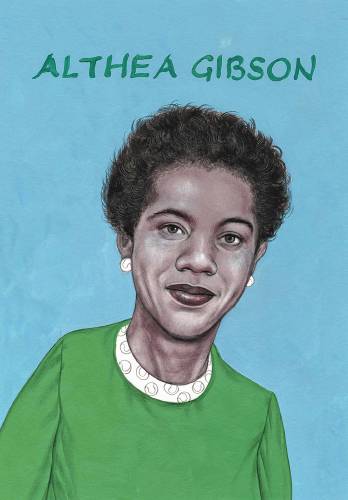

Now through May 26 you can view Kunz’s portraits of women, both legendary and obscure, at Stockbridge’s Norman Rockwell Museum.

The COVID quarantine was the mother of invention. While many of us spent idle hours creating elaborate mazes for Ping-Pong balls or mastering the complex art of flipping a water bottle to land upright, Kunz researched notable women and then daily, painted their portrait.

“I feel like I spent one day with an incredible woman and the next day with someone else,” the artist said during a press reception. “It really saved my sanity during the pandemic.”

It was during a boat ride in Maine during an artist’s residency there that spurred her interest in profiling pioneering women. She was told about a 19th century transgender woman, Jane Bates, who lived as a hermit and who drowned in Casco Bay.

“I started thinking about how many tragic stories about women are forgotten,” the illustrator said. “I decided finally to just paint portraits of whoever I could find. There’s nothing more complicated about the project than that.”

Kunz cast a wide net both globally and through centuries. A remarkable, anonymous portrait of a female artist hearkens to 40,000 BCE, the epoch of early cave paintings. The illustrator explained that recent anthropological research has proven that female hands created many of the primitive images. In creating the portrait of an early artist, she relied upon what scientists have suggested as to how people of that time would have appeared.

A portrait of writer and feminist Elizabeth Magie was nearby. Lost to the vagaries of history, she invented The Landlord Game, an early rendering of Monopoly. Her intention was to inform players as to the damages wrought by land grabbing by such barons as Carnegie and Rockefeller. Three decades after its creation, Charles Darrow redesigned her invention and made millions from the eternally popular pastime.

Not far away is a portrait of Elizabeth Abbott, an educator, who while recovering from polio, created the board game Candyland. Her intent was to create a diversion for children suffering from the affliction, while also teaching them patience and teamwork.

“I’m alone a lot in my studio,” Kunz said at one point, “so I get really excited by these stories, but I’m equally excited by visually painting them.”

Among the myriad works, you’ll find Beryl Markham, who was raised in present-day Kenya and at the age of 18 became the first racehorse trainer in the entire African continent. She was also the first person to fly solo from England to North America. Her book, “West with the Night,” is a literary classic that caused the novelist Ernest Hemingway to note that she “could write rings around all of us who consider ourselves as writers.”

There is not a historical leaf unturned. Kunz depicts St. Elizabeth of Hungary who in the 13th century renounced her title as princess. She then directed her wealth to the construction of a hospital where she served as a nurse. She was later canonized as a patron saint.

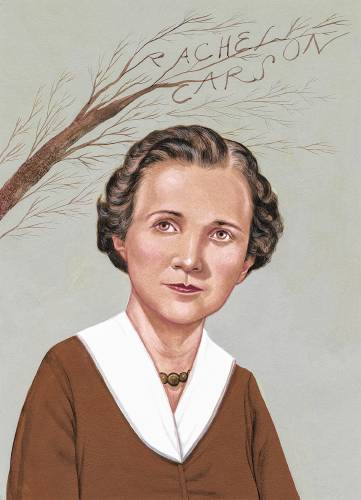

That the marine biologist Rachel Carson has not achieved some form of sainthood is a historical oversight. Her 1962 book, “Silent Spring,” was among the first to inform Americans as to the dangers of the promiscuous use of pesticides. Due to this writing, on several occasions her life was threatened. The book, however, became foundational to the modern environmental movement.

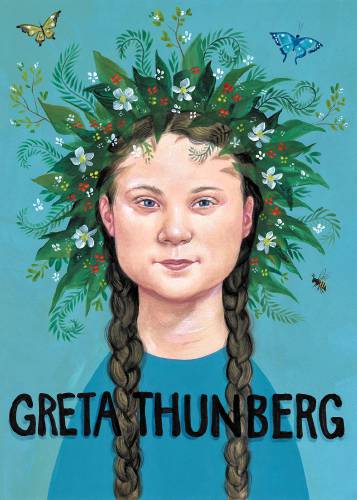

Many contemporary women are also chosen, ranging from the feminist author Gloria Steinem and the Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg to Ruby Bridges, the first African-American child to integrate a Southern elementary school.

The range is encyclopedic and each portrait carries with it a brief description of the individual. The exhibit is complemented with a companion catalogue, “Original Sisters: Portraits of Tenacity and Courage” (Pantheon Books). There are also videos from an interview with Kunz as well as a primer on how she creates images. An interactive video allows you to investigate various personalities while adding your own biography.

When her art schooling began, before embarking on a career of 45 years, Kunz was among the relatively few women in illustration. In a 2021 interview she noted that she “always felt a little bit out of place. I always felt a little bit like an outsider.” She also was aware of the deficit of female representation in art history.

“I’d always noticed,” she said, “that all of the history had pretty much to do with men and the male gaze.” Kunz has satirically distilled the issue in a book, “Another History of Art,” in which she imagines an alternate world where classic works were all created by women.

The artists range from Getrude Klimt and Paola Picasso to Vincenza van Gogh. One gallery displays these works juxtaposed with playful, earlier cover art featuring personalities such as the late comedian John Belushi, Reese Witherspoon and Mariah Carey.

“I’ve always felt lucky making money drawing pictures,” Kunz said during the reception. “What could be better?”

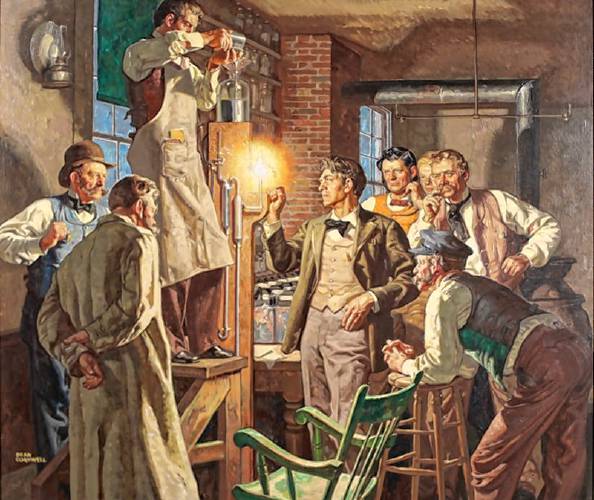

Also on view at the Rockwell is “Illustrators of Light: Rockwell, Wyeth, and Parrish from the Edison Mazda Collection.” The gallery show is devoted to the early commercial art, most never before publicly displayed, extolling the virtues of the tungsten light bulb. The well-known artists N.C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parrish, Dean Cornwell and Norman Rockwell were among the illustrators advertising the replacement of harsh, undependable carbon filament bulbs with the reliable softer glow of tungsten. In later, more lowbrow years, Mickey Mouse and Pluto would also be enlisted to promote the product.

The Edison Mazda name was used in marketing by both Westinghouse and General Electric, with the name Mazda referencing an ancient Persian mythical god of light and wisdom. The name was dropped after 1945.

General Electric was responsible for standardizing wiring, socket and bulb size at a time when there was once a confusing smorgasbord of eccentric choices to be found. By the 1930s bulbs could be purchased at five cents apiece and were rated to last some 207 hours.

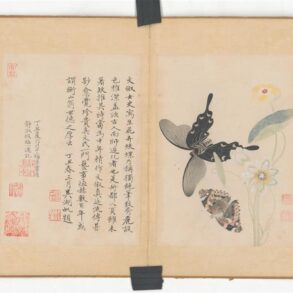

Among the images in the exhibit, Rockwell’s atmospheric 1920 painting “And the Symbol of Welcome is Light” is romantically unusual. Under a blue moon and Japanese lanterns, a family arrives at a party, with the scene backlit from an open door. Whereas Rockwell usually cast figures in sharp relief, they are indistinct and the dominant figure is light itself.

“Anita Kunz: Original Sisters, Portraits of Tenacity and Courage” continues through May 26. “Illustrators of Light: Rockwell, Wyeth, and Parrish from the Edison Mazda Collection” continues through Jan. 4, 2026.

The Rockwell Museum is open on weekdays (except for Wednesdays) from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., and from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays. Admission is $25 for adults and free for ages 18 and under.

More Arts for you

By using this site, you agree with our use of cookies to personalize your experience, measure ads and monitor how our site works to improve it for our users

Copyright © 2016 to 2024 by H.S. Gere & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.