Kamala Todd, a Métis-Cree community planner, filmmaker, and associate professor of professional practice in SFU’s department of Urban Studies, notes that the project as a whole raises many important issues around cultural policy and cultural space within the context of displacement of First Nations and impacts on their cultural infrastructure.

She notes that for years the Vancouver Art Gallery has been operating in the heart of the city, on unceded Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh territories, in a building that was what she calls an operational centre of colonization—as the law courts—with no dedicated space for the Indigenous arts and culture.

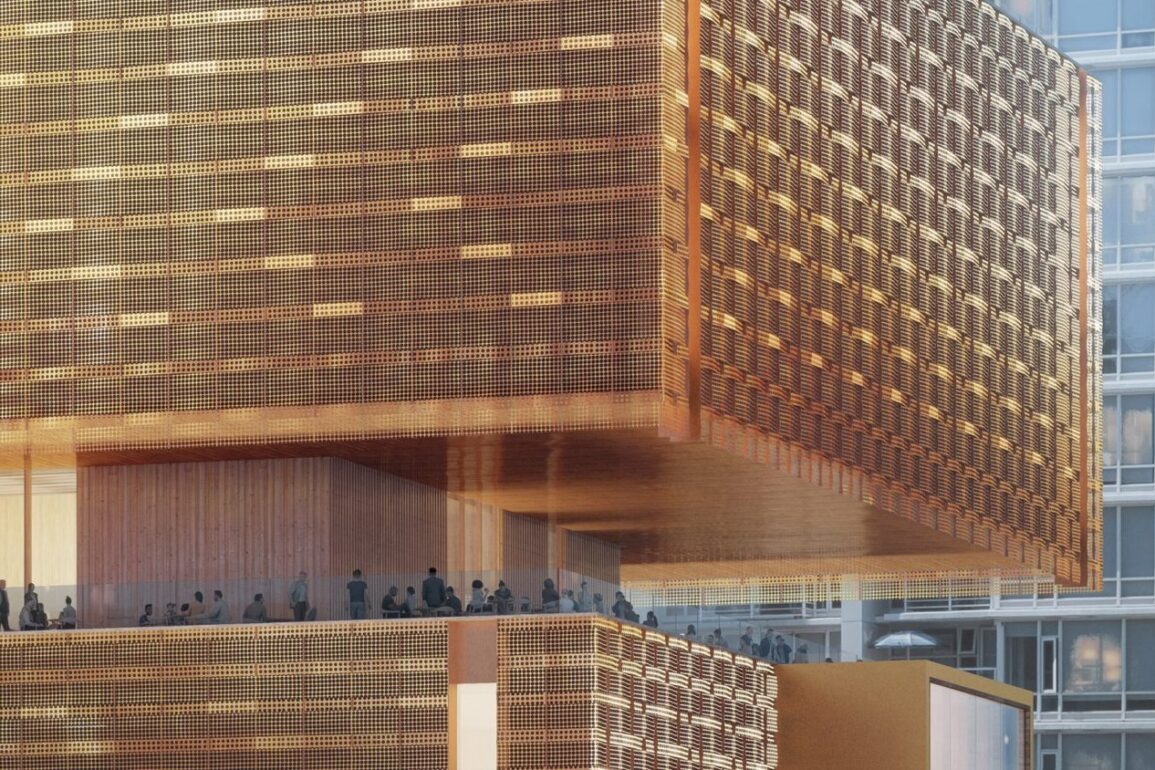

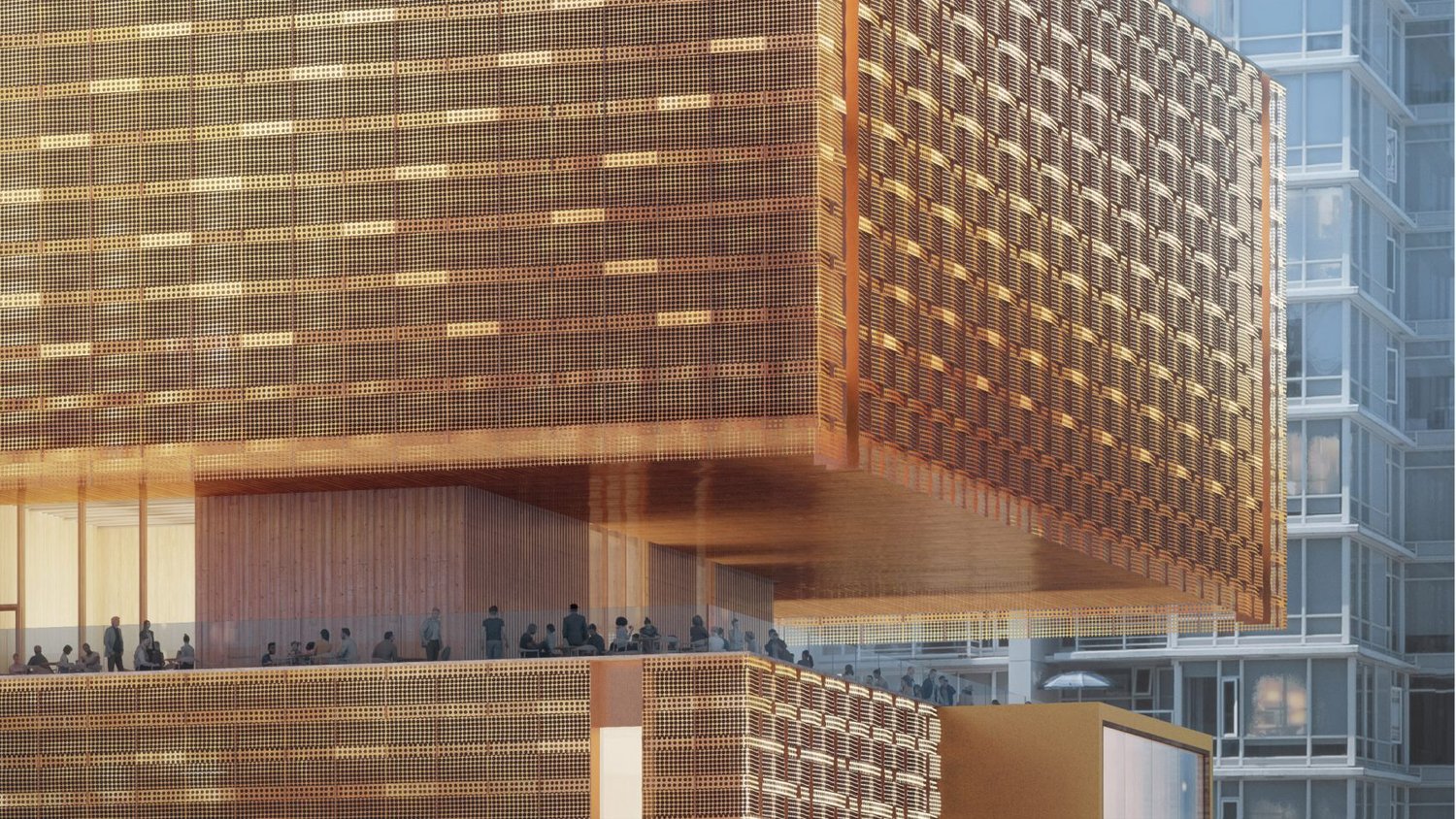

“The VAG has never had a permanent space for the local First Nations to practise and share their arts and culture in this major cultural institution on their lands,” Todd tells Stir. “The original building design for the new VAG perpetuated this displacement and erasure and did not reflect the astounding beauty of Salish cultural expressions or the rights of the local Nations to steward cultural infrastructure on their lands.

“While I was the City of Vancouver’s Indigenous Arts and Culture planner from 2018 to 2020, my feedback about the project focused on the need to rectify this erasure, and ensure that the new building design and development completely involve and reflect the rights and title holding Nations of Vancouver,” Todd says. From there, the architects worked with the local Indigenous artists for the design showcasing Salish weaving. Todd was hopeful that this involvement would also progress to Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh co-management of the new gallery.

“My first reaction when hearing about the scrapping of this project was deep concern for the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh artists who helped Indigenize the building design to make sure that this important cultural centre reflects the original arts and culture makers of these lands,” Todd adds. “From what I have learned, it sounds like the weaving designs will still be incorporated into any new building design. That is good news. I can only hope that with the involvement of the local artists and with the Vancouver UNDRIP [United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples] Strategy Calls to Action, these conversations are happening and we will see a renewed project that truly involves Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh in all areas of sharing arts and culture on their lands.”

This project is based upon a substantial land grant by the City of Vancouver, Todd points out. With the VAG starting from scratch in terms of its new design, it’s an opportunity for conversations with the local rights- and title-holding Nations about co-management, resource sharing, self-determination, and voice in such spaces as well as land-use decisions, she says.

“During my time with the Vancouver UNDRIP Strategy Task Force, I heard much concern and discussion about this,” Todd says. “In particular, there is work to do to redress the loss of lands, cultural spaces, and infrastructure for the local First Nations. It’s important to harness every opportunity to support restoration of land, cultural institutions, and cultural access.”

Reactions from elsewhere in the community acknowledge the VAG decision was fiscally necessary. Curtis Collins, director and chief curator of Whistler’s Audain Art Museum, calls the situation “unfortunate”.

“It’s a very unfortunate circumstance for B.C.’s cultural community because the VAG in many ways has been a central point in the artistic scene and it’s losing ground with this announcement,” Collins tells Stir. “Having said that I’m very sympathetic to Anthony’s dilemma in the sense that having to raise $600 million dollars in a very short period of time is almost an impossible task and they’ve finally come to the realization that that price tag just exceeded the reality of what is possible in a city the size of Vancouver….To be candid there have been murmurs for some time now that that price tag was not going to hold. I wasn’t surprised at all.”

Collins also laments the fact that 15 years in the making, the VAG has spent $60 million in planning and pre-construction costs so far. “That’s more than what this museum [the Audain Art Museum] cost eight years ago,” Collins points out. “There’s a small museum missing.

“I think the silver lining is I would hope that they would consider something of a scale that is more in keeping with the size of Vancouver and the needs of Vancouver’s cultural community but also engaging with a B.C.-based or Canadian architect,” he adds. “There’s lots of talent in this country and I think that would reinvigorate not only the public but all the contributors, public and corporate, to keep this project on the front burner.”