Writer, feminist, artist and activist Kathleen Thompson died Dec. 21 from liver failure caused by a three-year battle with breast cancer. She was 78.

Thompson was born on Sept. 12, 1946, in Chicago and moved to Oklahoma City in 1951 where she spent most of her young life alongside her parents, Leslie (Les) and Frances (Tracy) Thompson; two brothers, Paul and Michael; and two sisters, Tracy and Sara. While a student at U.S. Grant High School in Oklahoma City, she was elected student body president and was a member of the debate team. Thompson was also the Oklahoma City District Methodist Youth Fellowship president during her teen years.

In a 2007 Chicago Gay History interview, Thompson credits her Methodist minister father and English teacher mother for the equality and justice for all people mindset she’s had since an early age. She first got interested in the fight against racial injustice in the summer of 1963, when the city’s NAACP chapter protested against local amusements parks because Black people were not allowed entry.

Thompson said she got a phone call from a news person who told her that her Methodist Youth Fellowship group said they supported young Black people’s fight for civil rights. Her response was that she wanted white students to boycott the amusement parks. That resulted in her picture being on the front page of the newspaper. She said this was “not great courage” on her part.

She then went on to Northwestern University in Chicago where she earned her bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1968. While in college, Thompson was active in the anti-war movement against the Vietnam War. She told Chicago Gay History that she was in Grant Park during the 1968 DNC but was not injured or arrested.

Chicago became Thompson’s permanent lifelong home after she graduated from college. She said in her Chicago Gay History interview that “Chicago is the only city I would ever consider living in for any length of time … It’s a great place. I love the people here very much … I never want to leave.”

After Thompson graduated, she worked at a variety of jobs to help support her nascent writing career. These jobs included Northwestern University Press where she first read the “Bitch Manifesto” essay in the book Notes From the Second Year: Women’s Liberation, which prompted to befriend other feminist women. She decided to open Pride and Prejudice, a used bookstore at 3322 N. Halsted St.. The first feminist bookstore in Chicago, Pride and Prejudice became a springboard for a feminist collective that included a women’s rap group, pregnancy testing and abortion counseling as a part of the underground abortion group, the Jane Network. The collective also produced The Source, a women’s liberation directory.

Around that same time, Thompson got involved in the queer rights movement and started dating a woman for the first time. She and her other queer women friends started going to what became the Chicago Lesbian Liberation meetings and to bars where they could relax.

Over time, Pride and Prejudice became the Women’s Center with an artist’s collective, musical performances, a lesbian counseling center and a place to hold Family of Woman dance events. Thompson and her fellow queer friends also went to the early Chicago Pride marches (later parades) and demonstrations. She said in that Chicago Gay History interview that a fissure within the center caused her to get attacked because she was a bisexual woman. This led her to bow out of both the women’s and queer rights activist movements and focus on her writing career.

Thompson’s writing was prolific, and she became well-known with the publication of her first book, the 1974 feminist classic Against Rape, co-written with Andra Medea. That book broke the silence about rape in a lot of places around the world. It was banned by the apartheid-era South African government, a fact that Thompson would often say was one of her proudest accomplishments as a writer. The book emerged from the first Midwest conference about rape organized by Medea and held in a downtown Chicago YMCA in April 1972. The book had seven printings and was later serialized in hundreds of newspapers across the United States. It remained in print until 1990 and was used in rape crisis centers and college courses focused on women’s studies for many years. Thompson also toured the country to educate people about rape for a time in the 1970s.

Her next adult book was Feeding on Dreams (1994) about the harmful exploitation of the diet industry in the United States, co-authored with psychologist Diane Pinkert Epstein. That book landed her on The Oprah Winfrey Show for the first time. After that, she co-edited Facts on File’s Encyclopedia of Black Women (1997) and co-wrote the first narrative history of American Black women, A Shining Thread of Hope: The History of Black Women in America (1998), with preeminent historian Darlene Clark Hine.

In 1999 Thompson began her years-long collaboration with Hilary Mac Austin. Together they co-authored three print documentaries The Face of Our Past: Images of Black Women from Colonial America to the Present (1999), Children of the Depression (2000) and America’s Children: Picturing Childhood from Early America to the Present (2001). The Face of Our Past resulted in her second appearance with Oprah.

Their final book together was Examining the Evidence: Seven Strategies for Teaching with Primary Sources (2014), which won a Learning Magazine Teachers Choice Award in 2016. Thompson and Austin also teamed up to create the non-profit One History in 2003 with the goal to provide accurate historical information for students, teachers and the wider public.

Throughout her life, Thompson was first and foremost a writer. She loved books, stories and language. To pay the bills, she spent many years slogging through the trenches of educational publishing. As part of this work, in 1987 she co-founded the educational development house Sense and Nonsense with her sister-in-law, Jan Gleiter, also an accomplished writer.

Additionally, Thompson wrote over 100 children and young-adult focused books.

In 1978, Thompson met actor Michael (Mike) Nowak a month after he moved to Chicago from Detroit. They were in a scene study course taught by the Chicago actor and director Mike Nussbaum at St. Nicholas Theatre. After class one day, Thompson and Nowak went to the Gaslight Tavern across the street and Nowak’s friend from college, actor Judith Easton, who was also in the class, said “Did you see the way she was looking at you?” to him.

“I was impossibly young, naïve and clueless,” said Nowak. “However, the two of us happened to head to the restrooms at the same time and locked eyes. That was the start of our forty-six year journey together. I became office manager at St. Nicholas for a time. Kathleen lived exactly two blocks away. So, on my lunch hours, I would briskly walk to her place and we would make love, practically every day. We were insanely in love…and lust. Kathleen had been an integral part of Chicago’s Women’s Movement (honestly, she has not been recognized enough for her consequential contributions to the cause), and she made it clear early on that marriage was not an option. I shrugged. Okay. Our life together was an adventure, often challenging, sometimes painful, shaped by compromise—but always guided by love and respect. Isn’t that the case with any two strong-willed people who cast their lots with each other?”

Two years later in 1980, Thompson, Nowak and Easton decided that they wanted to do their own stage productions and they co-founded The Commons Theatre. The Commons was committed to feminism, but this fact was never mentioned in their literature. The founders decided that the audience could figure it out for themselves. They called it The Commons because they hoped the space would become a multi-arts venue, and for a while they did host art exhibitions.

Thompson took on the role of artistic director at The Commons, which made her one of the first women and first playwrights to hold that position in any Chicago theater. Over the course of six years, she had eight of her plays produced there.

Two of the most successful plays were Caught in the Act, a musical comedy which she co-wrote with Medea and Gleiter that featured an all-women cast and put the theater on the map, and Dashiell Hamlet which she co-wrote with Nowak, Nussbaum and Paul H. Thompson. The theater also produced Thompson’s I Shall Love You Forever, A Two Story House, Could This Be Heaven?, Private Investigations, Sidekicks and Kindness. She taught playwriting at Chicago Dramatist Workshop for 10 years alongside Nowak.

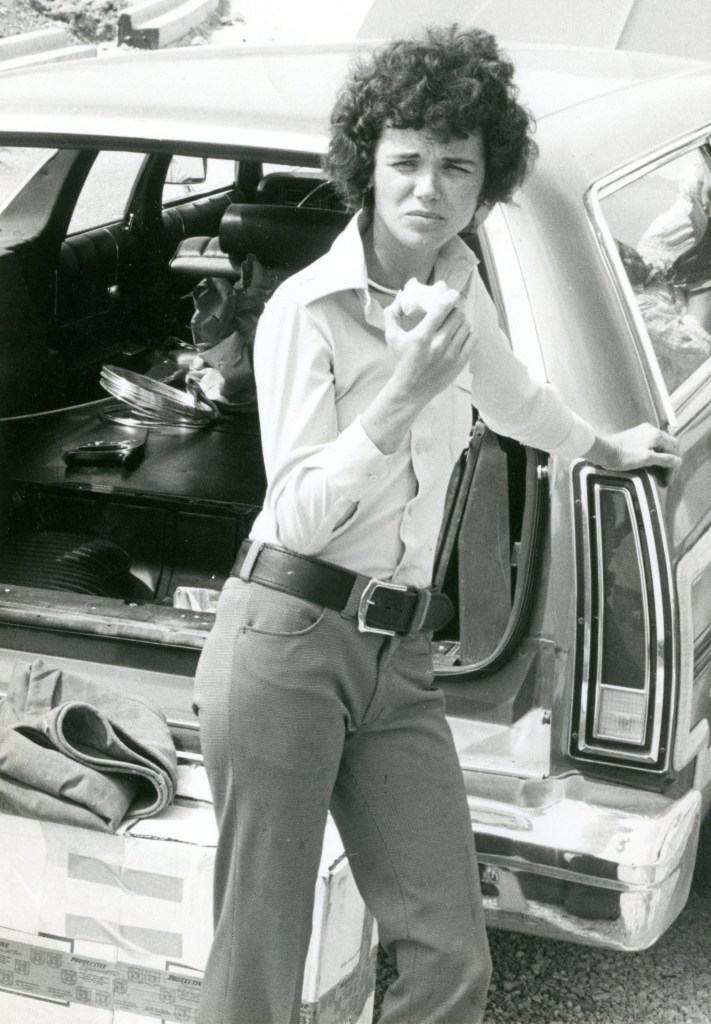

“Her style, funny and gentle, was under-appreciated in the 1980s Chicago theatre world that prized dark, gritty and, of course, male-dominated productions,” said Nowak. “Despite that, The Commons carved a name for itself in the burgeoning storefront theatre scene. And Kathleen and I must have hit some nerves along the way. Kathleen was known for her naturally wild and curly hair, and I suspect I shot my mouth off a little too much. I remember a person telling me about a party they attended, where the subject of Kathleen and me came up. ‘You mean John and Yoko?’ was the snarky comment. We were amused. There were a lot worse people to be compared to.”

Thompson and Nowak solidified their romantic relationship when they moved in with each other in 1983. They lived together in the Logan Square neighborhood for 24 years.

Because Thompson loved books so much she became known as “The Book Lady” in her Logan neighborhood. She would invite young people onto her porch so they could peruse children’s books, young adult publications and mature readers books and pick out the ones they wanted to keep which she offered to them for free. Her only rule was they could choose only one book a day.

After The Commons shuttered in 1990, Thompson continued to write while Nowak turned to radio at WGN, WCPT and WGCO. In the early 2000s, the couple’s focus veered into gardening and environmentalism. Thompson was a driving force in her neighborhood garden, Green on McLean, which was a fixture in her Logan Square neighborhood and helped drive the gang members away from the area. It was a place where people could meet and also find peaceful respite. They received an award from the 14th District Chicago Police for their role in removing the gang presence from their neighborhood.

Thompson taught herself how to build websites and created them for Nowak, her friends and the Midwest Ecological Landscape Alliance. These websites (and the flyers, posters and social media posts she made) are where her graphic artist abilities shone through.

In 2017, Nowak started Chicago Excellence in Gardening Awards (CEGA). Thompson was instrumental in the creation and maintenance of their website as well as database management, designing the all-weather signs that they used for the awards that they gave out to almost 300 gardeners over the past seven years.

Thompson recently started a very successful upcycling business called Strictly Hodgepodge and focused on making jewelry. She created fun, witty and striking pieces from vintage buttons, beads and scraps of paper that she dyed to make impressionistic collages.

“We were featured at the Logan Square Farmers Market for two seasons, where her work gained her a fan base of young and older folks who, even when they didn’t purchase her products, stopped to chat and learn about vintage jewelry from her seemingly endless storehouse of knowledge,” said Nowak.

In an effort to preserve early ‘70s Chicago LGBTQ+ and feminist movement history, Thompson arranged, alongside Newberry Library’s Curator of Modern Manuscripts and Archives Alison Hinderliter, for lesbian photographer Eunice Hundseth’s photographs to become part of the Newberry Library collection. This work began in the July 2020. Now this valuable and rare collection is available for research and general viewing purposes.

Additionally, Thompson and Austin collaborated with Newberry Library’s Director of Teacher Programs Kara Johnson to create classroom materials based on the Newberry’s collections. These materials included lesson plans and skills lessons related to teaching students how to use primary sources in K-12 classrooms.

Thompson was preceded in death by her parents and sister Sara Thompson. She is survived by Nowak, brothers Paul (Jan) and Michael (Shirley) Thompson and sister Tracy (Steve) Moncure, many nieces and nephews and countless chosen family members and friends.

Nowak said, “Kathleen might have been the kindest person I ever met. Yes, she was fierce when it came to standing up for women, children and minorities of all types. Her not-for-profit OneHistory.org is proof of that. But she learned something important from her Methodist minister father: It doesn’t hurt you to smile or to say hello to a stranger, and that small act has immediate and sometimes profound rewards. Especially later in life, you could count on Kathleen to compliment people she had never before met, telling them how much she liked that blouse or that hairstyle or that brooch or that jacket. The goodness she shared was real. The world is poorer without it.”

Siblings’ memories

Moncure said, “When you reach a certain age, your memories run together, and you’re left with impressions and truths and the stories that make you laugh or cry until you hurt. For Kathleen, I’m left with truths: she was brilliant, she was a caregiver, she was a fighter and she never intentionally hurt anyone. We will keep her beautiful soul in our hearts.”

Paul Thompson said, “Being two years older than I, Kathleen was my big sister, and I always looked up to her. This was the case even after she reportedly served me ammonia at a tea party and tried to poison me with her homemade gravy for lunch one day.

“I grew up in the shadow of both of my older sisters, but since I was closer in age to Kathleen, her shadow was bigger. This wasn’t that bad since her friends had to be nice to me, the boys because they thought being nice to her brother might make them look good to her. The girls thought I was cute. All of her former teachers assumed I must be smart and a good student like she was, and it usually took a while before they found out they were wrong. Kathleen was popular at school, not because she was pretty, which she was, but because she was smart, friendly, funny and kind. She was fearless and always stood up for the underdog. She was not someone others wanted to get into a battle of wits with, because they would surely lose.

“I realized that she was someone special when she was one of the leaders of a civil rights demonstration to desegregate an Oklahoma City amusement park swimming pool. She was 16 years old. She has been someone special ever since. In 1971, I moved to Chicago to live in a collective that she was part of. Kathleen had opened a feminist, used bookstore called Pride and Prejudice. It doubled as women’s center and, among other things, did pregnancy tests.

“She was a wonderful aunt to my children—her niece, Healy, and her nephews, Cooper and Spenser. Aunt Dean, as she was known, made learning fun with nature hikes and art projects. As far as I know, the only thing she couldn’t do was drive a car. Her first and last lesson ended when she crashed into the garage door. The world was a safer place because she didn’t drive. One thing remained the same over the years: she was always the smartest person in the room.

“I mentioned that she was fearless. Well, the other day I was talking to two of our cousins, telling them about Kathleen’s condition, and I said I didn’t think that she was afraid. They both said, ‘Kathleen was never afraid of anything.’ That’s not true, but it is close.”

Michael Thompson said, “Kathleen is my middle sister. From an early age she was different than most. While she enjoyed life and the people around her she was acutely aware of the injustices people were experiencing. From high school through college she pushed for equality and change. She worked to change people’s outlook throughout her life. Even living on a shoestring most of her life she was always willing to share with those who had less. Kathleen and Mike carried care packages in the trunk of their car for the unhoused people they would see on the streets of Chicago. They truly cared. What my sister wanted me to understand was: Open your eyes, open your mind and open your heart.”

Close friends and collaborators’ memories

Austin said, “Kathleen is my best friend. Early on Kathleen was my mentor. Now we are compatriots. Kathleen brought insight but also humility to her involvement with Black women’s history. And the study of Black women’s history radically changed how she viewed women’s history and how she viewed the world.

Kathleen is smart, caring, insightful and funny, but she also suffers no fools. She has one of the strongest moral centers of anyone I have ever met. That could be tough sometimes when she expected others to have that same strong moral core. In recent years we spent a fair amount of time discussing the dangers of ‘snark,’ the difference between ‘kindness’ and ‘niceness,’ and the power of a good tree. I will never look at a magnificent tree without thinking of her. I love her. I will miss her more than I can express.”

Medea said, “If a life worth living is leaving the world better than when you found it, Kathleen did this throughout her life and did it right up to the end.

“Look at how varied her body of work is. That’s the common thread: seeing what was needed, no matter how hard, then doing it. Kathleen had a brilliant mind, a gift for finding beauty, and for encouraging others to create. She made it look easy. But behind it all, was fierce hard work.

“Most people knew Kathleen as brilliant, articulate, someone who built things first, that needed building. Tenacious. They might not have noticed her capacity to love.

“Kathleen didn’t do sentiment—no patience for it. But during her stay in the hospice, a few of us read one of Kathleen’s mysteries out loud. It was filled with love: Foster Avenue at midnight during the 1980s, before it gentrified; Svea’s Diner after the breakfast crowd; the sound of actors spilling out of a storefront theatre in the quiet after a show. Starving writers, scruffy actors, kids out where they shouldn’t be. Kathleen loved this town. It showed.

“I want to also share a recent poem that Kathleen wrote as her cancer was growing more lethal.

‘As you move closer to death,

everything you love becomes a sorrow

and, as it has always been, a joy.

The two become one,

indistinguishable,

inseparable,

like the promise of darkness

in a sunset

flaming across the sky.’”

Judy Handler, musician and lifelong friend of the Thompson family, said, My relationship with Kathleen is the longest and closest friendship that I have had and she has always been a very special person in my life.

I met her in the early ‘70s and we shared an apartment for a couple of years before I moved away from Chicago in 1976. We lived behind a storefront where she had a batik business, which meant there was frequently a piece of clothing soaking in dye in the bathtub and people from her classes walking in and out of the apartment at all hours of the day or night. I became swept up in various projects of Kathleen’s like staying up all night painting to get ready for a photography exhibit, preparing for women’s group meetings or getting ready for poetry readings. I also have vivid memories of eating large bags of M&Ms together while trying to quit smoking on a number of occasions. We were both often working for hours in the apartment; I would be practicing classical guitar and she would be writing. She loved to hear the guitar music as a backdrop to her work and has always been one of the most enthusiastic supporters of my music.

I could always talk to Kathleen about anything. She would invariably have an interesting, thoughtful and empathetic response. We knew each other so well that it was easy to talk no matter how much time had passed since our last visit.

Her many accomplishments are a reflection of her superior intelligence, curiosity, artistic nature, independence and a general caring for people and issues. She created a beautiful, full life completely on her own terms.

I have a list of books that Kathleen has recommended to me over the past few years. I am currently reading a book she suggested recently, which is comforting and makes me feel connected to her. I will be making my way down the list and will always feel her presence in my life through these books and the many, many memories that I have.

Hundseth said, “When I decided to open Susan B, the first women’s restaurant in Chicago, she came in and helped shovel garbage out of the little storefront on Broadway. It had been closed down by the health department and was a mess. So Kathleen and a bunch of other women came to help and we turned it into a women’s space. She also brought a couple of strong capable men to help including her brother Paul and friend Jim.

“Because I’d never cooked before, she gave me a great recipe for lentil soup which became a favorite. Another woman actually cooked for opening night. Kathleen played her autoharp along with Judy Handler on guitar that first night. She would also perform at special events at my restaurant.

“Kathleen was a helper. She even walked away from a major TV interview in the early 1970s during a rally in the loop because she wanted to support other rally-goers in the midst of a commotion that sprung up.

“She was a generous, smart, talented, educated, socially adept, well-spoken and a real beauty, inside and out. I will miss her for as long as I live.”

Dr. Wanda A. Hendricks, University of South Carolina Department of History Professor Emerita, said, “I knew of Kathleen long before I actually met her in person. She and Darlene Clark Hine, my major professor and one of the most prominent Black women’s historians in the country, were friends and collaborated on one of the first comprehensive narrative histories of Black women in the United States, A Shining Thread of Hope: The History of Black Women in America. Kathleen’s commitment to highlighting the significance of Black women’s history was so unwavering that it was not unusual for her to attend conferences and meetings at the Association for the Study of African American Life and History and the Association of Black Women’s Historians—the oldest African American History organization in the country and the oldest Black women’s history organization in the country.

“When I was asked by Darlene Clark Hine to be one of seven Senior Editors on the Black Women in America: Second Edition encyclopedia I engaged with Kathleen quite a bit. It was a massive project—updating the previous encyclopedia, Black Women In America: An Historical Encyclopedia published in 1993 and expanding it from two volumes to three. Kathleen was a delightful person to work with, tenacious in her research and editing and was as adept at contextualizing the lives and histories of Black women as the six academic scholars were.

“Moreover, she was always kind and very generous with her time. As I moved through the academic world, we often had discussions about the unique differences between academic presses and trade presses and which would be better and the most useful places to publish my own books.

“I am truly saddened by her death. Her family, friends and all of those who know her have my deepest sympathy.”

Hinderliter said, “I was always wowed by her intellect and clear-headedness. She was a wonderful thinker and writer and had a great sense of humor. I will miss her very much.”

Johnson said, “Kathleen was a supreme scholar and humanitarian. She has transformed how we do history in innumerable ways. Kathleen also had whimsical side and a lot of hidden talents like jewelry making. She made it a point to repair things and turn them into sellable items so they would not end up in landfills. This is one of many examples of her ecological mindset.”

A memorial service will take place at a later date. Details are forthcoming.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content