Last November in New York, Maurizio Cattelan’s 2021 duct-taped banana sculpture Comedian sold at Sotheby’s for $6.2m. To the wider world, both the piece and the price might have seemed like a joke. But the last big-ticket art auctions of 2024 produced plenty of other talking-points that were worth taking seriously.

Cattelan says he created his Duchampian prank as “a sincere commentary and a reflection” on the excesses of the art market. But like Banksy, whose half-shredded painting, then titled Girl with Balloon (2006), was resold at auction for a record $25.4m in 2021, Cattelan has discovered that artists’ attempts at such subversion tend to end up being subverted by the market itself, leaving the entire art world looking a bit absurd.

Bananamania could not completely distract from the cooler realities on display at these New York evening sales. Overall, this biannual Modern and contemporary series at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips, comprising 15 live auctions, raised $1.3bn (with fees), a decline of 41% on the previous November.

The international art market has been in a slump for the last two years, and insiders point out that the immediate aftermath of a US presidential election was not the ideal gathering time for the auction houses. Yet the boost in the value of stocks, the dollar and cryptocurrencies following Donald Trump’s triumph suggested to some that the ultra-wealthy might rediscover their enthusiasm for splashing out on art.

Apart from the banana, and a few other less hype-generating exceptions, this did not prove to be the case. Time and again, works sold within estimate to one or two bids, or were left unsold, and collectors were noticeably less willing to underwrite sales with third-party guarantees, which in recent years have underpinned prices at the top of the auction market. In November 2023, 71% of the value of sales at these New York evening auctions was guaranteed by the auction house or third parties. Last November, the figure dropped to 50%, according to data supplied by the London-based art market analysts Pi-eX.

“The high-profile ‘banana sale’ drew attention away from broader market trends that highlight significant challenges in the art market,” says Christine Bourron, the chief executive of Pi-eX. “Supply constraints, reduced auction volume, fewer top-tier lots and a notable decline in third-party guarantees all indicate a softening environment.”

As ever, big-name trophies from prestigious single-owner collections sparked the most sustained competition. Works from the estate of the Palm Beach-based beauty products mogul Sydell Miller led the week, grossing $216m in Sotheby’s evening sale of Modern art. Just seven of the 25 offered lots were covered by third-party guarantees, including a large Claude Monet Nymphéas (water lilies) painting from around 1914-17. With a stamped signature on the back, it was not considered by experts to be one of the more impressive of the 300 or so iterations of the celebrated subject. Yet a “Monet water-lily painting” remains one of the international art market’s most desirable brand objects. Bidding from Asia pushed the price to $65.5m with fees, broadly in line with the $60m presale estimate.

Magritte’s Surreal appeal

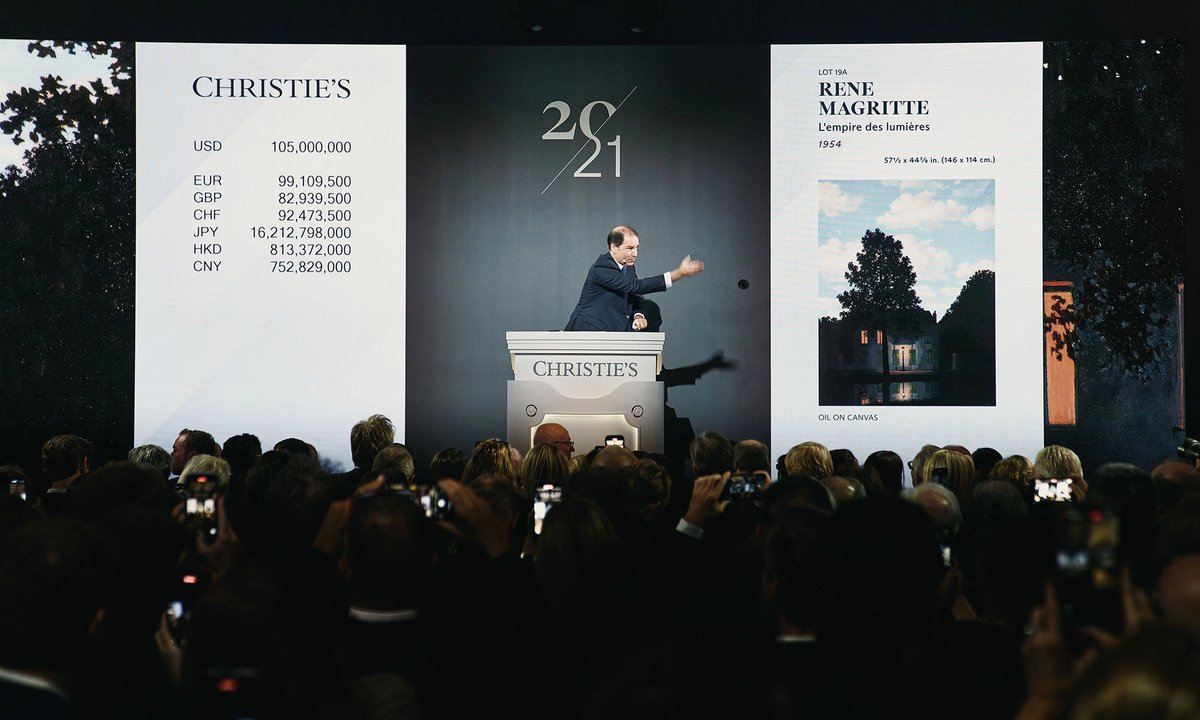

The one out-and-out masterpiece on offer in New York was a 1954 version of René Magritte’s Empire of Light, the most prized work in Christie’s evening sale of the collection of the Manhattan interior decorator and socialite, Mica Erdegun. It was widely regarded as one of the finest of the 17 versions Magritte painted in oil of this famous subject and was certain to sell for at least $95m, courtesy of a third party guarantor, widely identified as the Miami-based hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin.

“It’s the trophy of all trophies, an example of the true masterpiece market,” said Brett Gorvy, the co-founder of the international gallery, Lévy Gorvy Dayan, prior to its sale. “There will be a club of just four to six people who could bid on it.” On the night, it attracted just two bidders, who took ten minutes to inch the price up to $121.2m (with fees), where it was knocked down to the guarantor.

The price at Christie’s price was impressive and set an auction record for Magritte. But given that this world-famous image was billed by the auction house as the greatest Surrealist painting to have ever appeared on the auction market, should it have made more?

Only billionaires could have comfortably afforded this Magritte trophy. According to Forbes, there are currently 2,781 billionaires in the world. Just two of them bid for this bluest of blue-chip paintings. Has buying art become something that only interests the 0.1%, even among the billionaire class?

Buyers of works by hot young artists at auction also seem to have become a select club. This November, Sotheby’s hitherto-hip biannual format of The Now sale, devoted to “art executed in the last 20 years, offering the most exciting, cutting edge works on the market”, featured just three works by artists under the age of 40.

Back in May 2022, when speculative demand for works by emerging artists was at its frothiest, Sotheby’s The Now offering raised $72.9m from 23 lots. This time round ten works yielded a far more modest $16.5m, $6.2m of which came from the 64-year-old Cattelan’s banana.

Once-feted names like Flora Yukhnovich and Amoako Boafo were entirely absent from the auction week, while works by Avery Singer and Christina Quarles failed to sell. All four youthful artists, along with a crowd of other Wunderkinder, had notched up hefty seven-figure auction prices within the last four years.

“The rocket fuel propelling them was free money and Asian demand. Those two engines stopped brutally,” says Alain Servais, a Brussels-based collector, referring to how interest rates have risen and how China’s economy has slowed over the last two years.

Regardless of political inclination, those involved in the business of selling art are hoping that president-elect Trump’s promised package of tax cuts and deregulation will reinvigorate demand. The recent surge in the value of cryptocurrencies certainly had a demonstrable effect on the price of Sotheby’s banana, which had already inspired the launch of a popular meme-coin. At least four of the seven bidders were known to be crypto investors.

The S&P and Nasdaq stock indexes are already at all-time highs. If President Trump fulfils his laissez-faire agenda, there is a strong possibility that American millionaires and billionaires in sectors like finance, tech, crypto, oil and health will become inordinately enriched. But will they buy art, particularly if it does not have an attached meme-coin?

Those who study the art market, rather than trade in it, have their doubts. They are aware that art sales have flatlined in recent years, in contrast to the growth of luxury markets and high-net-worth wealth.

Art fairs for being seen, not buying

Roman Kräussl, a professor of finance at Bayes Business School in London, who has published research papers on the performance of art as an asset class, says art is no longer a “must have” for the wealthy, especially its younger international demographic. “It is still a must to be seen at Frieze and Art Basel, and maybe in Dubai and Hong Kong, but it is more like a need to attend, not to own,” Kräussl says.

For David Kusin, the founder of a Dallas-based consultancy specialising in art economics, this might have something to do with the fact that the wealthy perceive art as a problematic “investment of passion.”

“For the past 15 years, there have been 13 years of sales stagnation leading up to 2023 and 2024, when there have been actual sales declines,” says Kusin, whose own exhaustively researched price data from 150 submarkets indicate that since 1988, the aggregate value of fine art, decorative art and antiquities has declined 23%, allowing for inflation. “It is not a two-year sales slump. It is a slow motion, generation-long problem,” Kusin adds. “There’s a growing realisation that art is a wasting asset.”

Who knows? Maybe collecting art will once again become the thing the wealthy want to do. Nonetheless, the fact remains that serious art collecting is a rarefied activity that tends to flourish in stable, affluent democracies. In a world with less and less stability, collecting art drops down the to-do list, even for the super-rich, particularly if there isn’t easy money to be made out of it.

After all, why would Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, want to spend $100 million on a painting—or $6m on a banana—when he can have so much fun de-stabilising entire G7 democracies like Britain and Germany on X for free?

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content