“And now we come to the Leonardo,” Jussi Pylkkänen told the gathered audience of bidders, reporters, and Christie’s staff in front of him, “Previously in the collections of three kings of England.”

For 19 minutes, everyone inside the packed Manhattan auction room was transfixed by the spectacle unfolding in front of them. A frenzy of bidding was taking place before their eyes, beginning with an ask of US$10 million and climbing swiftly to US$284 million; before there was a pause for breath and a moment to consider the history that was taking place.

On the auction block was the Leonardo da Vinci attributed Salvator Mundi (Latin for “Savior of the World”), the first da Vinci artwork discovered in over a century and one that was originally dismissed as a reproduction by experts.

The lull in bidding broke as a hand shot into the air with a cry of “$300 million,” kicking off a further nine minutes of bidding that was ended by a sentence never heard in the art world before.

“$400 million,” called Christie’s Alex Rotter, bracing himself against a wall as if the enormity of his words threatened to knock him over.

The room collectively gasped, claps rang out, and audience members opened their phone cameras, sensing a final blow had been dealt. No more bids came and Pylkkänen’s hammer finally came down with a crisp click, setting a new record for the highest price ever paid for an artwork at US$450,312,500 (AU$593,511,875) including buyer’s fees.

The knock of the auctioneer’s hammer was the moment that produced headlines around the world, but the story of how da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi came to that New York auction room deserved more column inches.

Not simply because it destroyed a record set just two years earlier — when Christie’s sold Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger for US$179,364,992 (AUD$223,255,605) — but because it revealed a glimpse into the art market’s murky underbelly.

Far from the glamour of the Rockefeller Centre where the auction was held, a network of unremarkable warehouses in Geneva (alongside similar facilities worldwide) hide the most valuable art collection on the planet — including, at points, Salvator Mundi.

A Port Without Ships

Most who visit Geneva remember the Swiss city for its historic buildings, expensive restaurants, and the Jet d’Eau de Genève rising from the lake’s surface. Hidden behind this veneer of old-time Europe, however, are countless objects of near priceless value, secretly kept and often anonymously owned in the little-known location of the Geneva Freeport.

Southwest of the city centre, tucked away between the gloomy railyard of Lancy-Pont-Rouge and a lowrise McDonald’s, is a discreet complex of warehouses that contains likely the largest collection of art and valuables in the world. It’s the kind of building you could walk past every day for a lifetime and never remember its features, but the unremarkable site masks a Fort Knox-like construction that’s critical infrastructure for the international art market to operate as it does today.

For context, the collection owned by The National Gallery of Australia counts around 155,000 artworks, while the Musée du Louvre boasts a collection of more than 500,000 objects and artworks. As reported by the specialist art journal Connaissances des Arts, in 2013 the Geneva Freeport housed between 1.2 and 1.3 million artworks, making it the world’s largest art collection that no one can see.

But what does the Geneva Freeport — and its cousin complexes — actually do? Part of the answer is it’s a storage facility for valuable objects like artwork, antiquities, gemstones, bullion, and beyond. The other part of the answer is it acts as a kind of duty-free area, offering tax-free storage of such goods and a location for buyers and sellers to trade without incurring taxes.

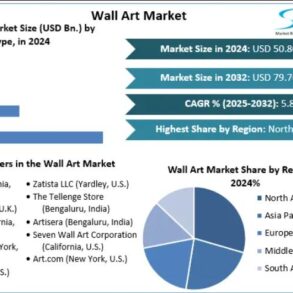

As estimated by the Swiss Federal Audit Office in its 2014 annual report, the value of Switzerland’s duty-free areas was worth more than CHF 100 billion (AU$121 billion). Of course, that number is certainly much higher following the art market boom in recent years, where the top 100 auction lots of 2022, ’23, and ’24 — 300 artworks — combined to achieve US$8.3 billion (AU$13.4 billion) in trade.

What is the actual value of the Geneva Freeport’s contents? No one knows for sure, but an estimate of several hundred billion dollars would be conservative today.

Turning Grain Into Gold

Freeports have existed for centuries, with the earliest successful example being found in Livorno, Italy, during the 16th century. They were created to incentivise trade through the cities that established them, offering merchant ships more favourable terms to restock their supplies or warehouse their goods, with colonial-era examples including Hong Kong and Singapore as Europeans stepped up trade with Asia.

While freeports were traditionally located in ocean port cities to allow merchant ships to access them, the Geneva Freeport was established in 1888 as a storage facility more than a trading destination. The Geneva Freeport was used to store the city’s grain provisions and other key goods like wool, coal, and food, and remains majority-owned by the Genevan government to this day.

Its uses evolved with the times and by the end of the Second World War, it started to be used to store the kinds of precious objects it’s known for today. In addition to gold bullion, the network of warehouses became home to expensive cars, vintage wine, and ancient artefacts, while it’s also reported that by 1952 one merchant was using the Geneva Freeport to store 10,000 Vespas.

“A generation ago, these goods were cars, wine, and gold,” writes Sam Knight for The New Yorker. “More recently, they have been works of art.”

Today, the Geneva Freeport has more than 100,000m² that can be rented out, with a staff of experts and a suite of services you’d probably expect to find in the basements of the world’s largest museums — not anonymous warehouses in the suburbs of Geneva.

The Work Of Warehousing

It’s no accident that Salvator Mundi was stored briefly in the depths of the Geneva Freeport. Before it was sold by Christie’s in New York, it was owned by the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev. He had purchased the painting through his art advisor, Yves Bouvier, the CEO of Natural Le Coultre at the time and one of the Geneva Freeport’s larger tenants (currently, the firm boasts 35,000 m2 of secure storage).

Bouvier’s family assumed ownership of Natural Le Coultre in the early 1980s and after taking over from his father in the late 90s, he shed the furniture storage and transport arm of the business to focus on art. In addition to being an important tenant of the Geneva Freeport, under Bouvier’s leadership, his family holdings took a 5% ownership stake in the facility.

After identifying a growing appetite for freeport services, Bouvier exported his version of the centuries-old concept around the world, opening freeports in Singapore in 2010 and Luxembourg in 2014. Business was booming, and as with so many goods and services enjoyed by the 1%, if you need to ask how much it costs, you probably can’t afford it.

According to The Economist in 2013, fees vary but are, “typically around US$1,000 a year for a medium-sized painting and US$5,000-12,000 to fill a small room.” Over a decade later, it’s not hard to imagine that costs are significantly higher today.

It sounds like a lot of money on the face of it. But considering the tax savings that can be achieved using a facility like the Geneva Freeport, there’s little wonder it houses more art and antiquities than most museums large combined.

To do some very rough calculations, imagine you purchased a painting for $10 million. To bring it into Australia you’d have to pay import duties of 5% and import GST of 10%, bringing your total taxes to $1.55 million before freight or insurance costs.

While Geneva isn’t the most practical location for Australian art collectors, just imagine a French art collector who had purchased a painting from an American dealer for €10 million. Without the costs of freight or insurance, their duty (2.5%) and VAT (20%) obligations would be around €2.5 million.

If the art collector has purchased the work as an investment — rather than something they’d like to hang on their wall at home — the prospect of saving millions in taxes owed is worth paying good money for.

Another benefit of facilities within the Geneva Freeport is the ability for tenants to trade among themselves without needing to pay taxes such as VAT. If the French art collector finds a buyer for their painting who’s prepared to pay €15 million, they’ll potentially enjoy the €5 million profit tax-free.

Keep It Secret, Keep It Safe

If you found yourself in the Geneva Freeport during the apocalypse, there’s little chance you’d want to leave. The warehouses are earthquake-proof and are equipped with an inert gas fire extinguishing system, with access through unmarked armoured doors only granted to those who pass the biometric security systems.

To ensure all artefacts in storage remain in the same condition they arrived in, secure rooms are controlled to strict temperature and hygrometric ranges to prevent damage from humidity or other contaminants. When you consider there are likely hundreds of thousands of objects that have remained stored within the Geneva Freeport for decades, such controls are critical to maintaining the trust of clients using the vaults.

However, if a client is storing an artwork or antiquity that’s seen better days, the Geneva Freeport also offers the services of in-house art restorers, photographers, and framers. Clients can confirm the authenticity of any artwork they’re storing by using a suite of high-definition painting scanners to analyse the composition of their artwork with forensic detail.

The Geneva Freeport also offers insurance for collections kept within its warehouses, transportation arrangements tailored to meet the “nature and sensitivity of your products,” and meticulous inventory management. Beyond the services offered by the Geneva Freeport itself, the largest tenants are typically sub-letting companies such as the Bouvier-owned Natural Le Coultre.

Firms like Natural Le Coultre offer another layer of privacy and even more granular management services. It provides its clients with everything from showroom space for exhibiting objects to collection management with cataloguing, photography, and condition reports services. If a museum-grade service is needed, it’s offered within the walls of the Geneva Freeport.

Knock, Knock

Much like the legendary Swiss banking services, where accounts could once be opened and managed without checks or identification, the Geneva Freeport formerly worked with anonymous clients without inventorying the contents of their storage spaces.

Today, stricter inventory management systems and more details client checks have become required; though almost all of the Geneva Freeport’s contents remain publicly unknown. Beyond information learned through police raids and court cases, it’s understood that more than 40% of the contents of the warehouses are artwork, including more than 1,000 works by Picasso.

One of the Geneva Freeport warehouses is also reported to be the “world’s biggest wine cellar,” according to SwissInfo.

“Around three million bottles of vintage wine, mostly from Bordeaux, are sitting in wooden cases in the vaults of the building, slowly maturing at an ideal temperature and gaining interest for their owners,” the publication claims.

What Could Go Wrong?

Where serious money is to be saved or made, less-than-savoury actors are never far away. The most prominent legal proceedings arising from freeport disputes involve both Bouvier and his former client Dmitry Rybolovlev, with the Salvator Mundi right in the middle of it all.

Known as The Bouvier Affair, Rybolovlev alleged that Bouvier had systematically overcharged him for artworks over 11 years while acting as his art advisor. During that period, Rybolovlev amassed one of the greatest art collections in modern times, purchasing 37 different artworks for around US$2 billion.

It was by accident that Rybolovlev learned of the alleged overcharging after discovering Bouvier had paid just US$80 million for Salvator Mundi, before ensuring it was sold to the Russian billionaire for US$127.5 million.

Rybolovlev believed he found similar mark-ups in the sale of other paintings that Bouvier had sourced or sold to him — to the tune of around US$1 billion — leading him to file lawsuits in courts in Monaco, Switzerland, France, Hong Kong, Singapore, and the United States.

Legal proceedings raged around the world for more than a decade, but the financial losses and betrayed friendship meant Rybolovlev could no longer enjoy the paintings he had purchased through Bouvier. He began to sell them off, with the Salvator Mundi being the most famous artwork that arrived on the market because of The Bouvier Affair (also the sale that returned Rybolovlev the most money).

While certainly the most high-profile, The Bouvier Affair wasn’t the first time the Geneva Freeport was linked to allegations of criminal activity. The first serious case of a police investigation was in 1995 when Italian police raided a storeroom linked to art dealer Giacomo Medici. By the time the last wooden crate had been searched, investigators had uncovered 10,000 antiquities valued at US$35 million (AU$47.3 million), leading to a tightening of laws around Swiss duty-free areas.

Despite these changes, Geneva police located 200 ancient Egyptian artifacts in 2003 that had been illegally trafficked, while 2010 saw the discovery of a Roman sarcophagus that had been looted from a site in Southern Turkey.

In 2013 another scandal rocked the Geneva Freeport when Swiss authorities found nine antiquities that had been looted from sites in Syria, Yemen, and Lybia and stored for several years in the Genevan warehouse. What made this case particularly headline-grabbing was the source of the antiquities, suspected to have been looted by members of the ISIS terrorist network who were estimated to have been stealing up to £250 million (AU$456 million) of ancient Syrian and Iraqi artefacts a year.

Regulations relating to Swiss freeports continued to tighten; the 2014 annual report by the Swiss Federal Audit Office (SFAO) was damning. The office described duty-free areas as “still largely unknown and unexplored by the federal authorities,” and that “the SFAO believes that the current control system is deficient and is unable to ensure that illegal activity is restricted.”

The most recent scrutiny from regulators came in 2019 when the European parliament heard the report of the Special Committee on Financial Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance, which outlined that “apart from secure storage, the motivations for the use of free ports include a high degree of secrecy and the deferral of import duties and indirect taxes.”

Additionally, it noted that “money laundering risks in free ports are directly associated with money

laundering risks in the substitute assets market,” while also blaming changes to banking regulations as the reason behind the growth in popularity of alternative asset classes.

Specifically, that “the end of banking secrecy has led to the emergence of investment in new assets such as art, which has led to rapid growth of the art market in recent years; stresses that free zones provide them with a safe and widely disregarded storage space, where trade can be conducted untaxed and ownership can be concealed, while art itself remains an unregulated market, due to factors such as the difficulty of determining market prices and finding specialists; points out that, for example, it is easier to move a valuable painting to the other side of the world than a similar amount of money.”

Aesthetic Ethics

Beyond the legal challenges that facilities like the Geneva Freeport have faced in recent decades, many within the art community deplore their use as they deprive the general public of enjoying the rare masterpieces hidden within them.

While art has increasingly become just another category for the world’s wealthiest to deploy capital into, producing it has been one of the most consistent human pursuits for tens of thousands of years. Just as cave paintings were created 40,000 years ago as a record for future generations, so too were countless other masterpieces created to showcase the concerns of the time.

Will Gompertz visited the Geneva Freeport in 2016 for the BBC and painted an unambiguously gloomy picture of his experience within its climate-controlled armoured walls.

“I found the visit a rather sad and bleak experience,” Gompertz described. “If there are really a million artworks in there, all of which were created to be seen and enjoyed, it seems a travesty to the point of immorality.”

The Salvator Mundi is a relatively rare example of an important freeport-stored artwork that may eventually be offered for public consumption. Following the sale, the auction house confirmed the painting was destined to be displayed in the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which appeared a likelihood after it was revealed that the buyer was Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud (acting on behalf of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, or MBS).

According to an investigation by the BBC published at the end of 2024 that spoke with Bernard Haykel, a Professor of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University who communicates regularly with MBS, this is broadly still the plan, though the destination won’t be the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

“I want to build a very large museum in Riyadh,” Haykel quotes MBS as saying. “And I want an anchor object that will attract people, just like the Mona Lisa does.”

That anchor will be the Salvator Mundi. In the meantime, the Haykel reports that despite rumours the painting was hanging in the Crown Prince’s yacht, it has returned to a storage facility in Geneva — perhaps even the Geneva Freeport.

While there’s certainly some cause for melancholy about the state of freeports today, one art dealer interviewed by The New York Times on the subject offered a ray of hope to those lamenting hidden artworks. All we need to do is wait.

“Even if it stays there for the lifetime of the collector,” said Ezra Chowaiki, “It’s not going to be there forever. It will come out.”