Many artists have used cyanotype photography since British inventor Sir John Herschel discovered the technique in 1842. After combining two nontoxic chemical solutions derived from salts and iron, Herschel coated paper with the mix, placed objects such as ferns or engravings on the treated paper, then exposed the works to sunlight. The final step was rinsing the paper with cold water, which created a negative photogram — the image of a white object on a deep Prussian blue background.

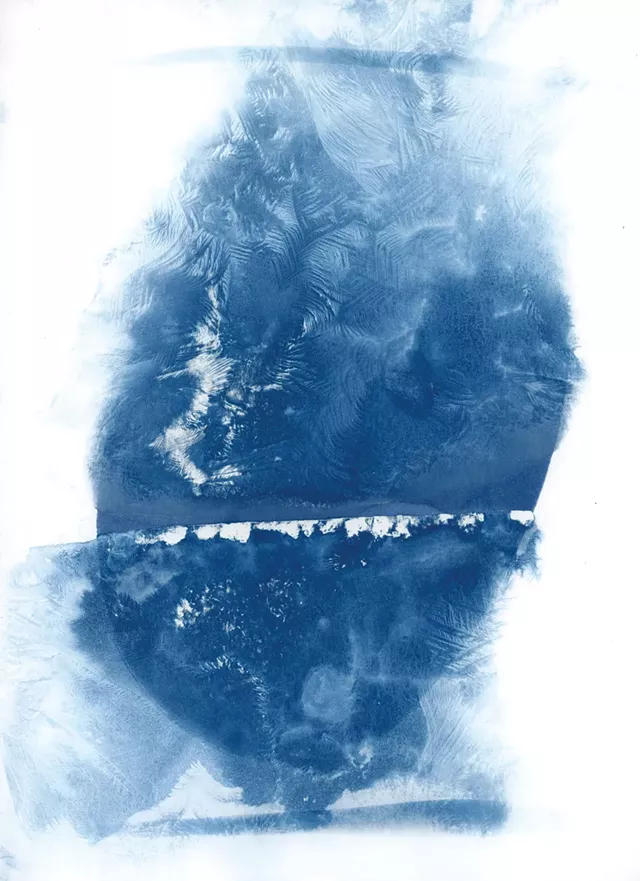

Huntington photographer and installation artist Renée Greenlee takes that natural process one step further: She uses water from Vermont’s Lake Champlain watershed as her subject. Greenlee brings treated, dried pieces of silk or watercolor paper in a lighttight bag to the edges of ponds, streams and rivers, where she either pours a small amount of water on them, letting them dry on land, or lays them along the shoreline, in partial contact with the water. The results are “collaborations with nature,” as she describes her work — direct imprints of the waterscape. (She rinses them in her sink at home.)

“Blue Alchemy: At the Water’s Edge,” arranged by state curator David Schutz in the Vermont Supreme Court Gallery, gathers cyanotypes that Greenlee has made since 2019. She created them at Johns Brook, near her home; at the Horseshoe Bend swimming area in Huntington; by the Winooski River at Volunteers’ Green in Richmond; at points along Lake Champlain; and on temporary spots of snowmelt. In addition to single works on paper, the exhibition includes a triptych on paper and two trios of 9-foot-long silk panels.

The cyanotypes, labeled with dates, locations and the weather that day, span a range of deep and lighter blues. (Colors change during the development process, and Greenlee sometimes documents that ephemeral progression in photos.) The works’ endless variety is a result of the elements: Some are patterned with ice crystals, while others display runnels of liquid caused by wind. Temperatures and the length of exposure also affect the works. Greenlee occasionally leaves them outside overnight if the day is cloudy or snow has drifted over them.

“The process doesn’t get consistent results; it depends on the climate — which is what this work is about,” Greenlee said as she showed Seven Days her cyanotypes.

Climate change is a central concern in works such as “Pentimento: Flood I & II.” Greenlee cyanotyped the 22-by-30-inch piece of paper twice in the same place — on July 11, 2023, and July 9, 2024, when unprecedentedly destructive flooding in consecutive years had inundated the spot at the confluence of the Winooski and Huntington rivers. The work darkens in hue gradually from sea green at the top to a blackish blue at the bottom, its composition affected by “whatever chemicals were being swept away — fuel, wastewater, everything,” Greenlee noted.

Several other works reference climate change. Greenlee made “Solastalgia,” a work on paper, on February 25, 2024 — during the world’s warmest February on record. One of her silk panels came from a series of 12 she made in response to the 2023 floods for an outdoor installation in Burlington. Books by environmental writers Rachel Carson and Robert Macfarlane inspired other works in the show.

In a few cases, Greenlee painted her cyanotype solution on paper in a central shape, resulting in works such as “Heart Shaped Spring Equinox,” with its abstract dark-blue heart, from which veinlike runs of lighter blue extend on a white background. In most cases, though, she coated the entire surface so that the works resemble close-ups of water.

Greenlee is from a small Pennsylvania town outside Pittsburgh and earned master’s degrees in communication and theology. In 2014, she enrolled in a nine-month photography program at the now-shuttered Pittsburgh Filmmakers media arts center, where she first learned about cyanotype.

In Vermont, where she and her husband settled in 2015, Greenlee splits her practice between documentary photography for nonprofits, film photography and her cyanotypes. She started experimenting with the medium soon after her move as a way of combating the homesickness she felt.

Eventually the experiments evolved into “Blue Alchemy,” an ongoing body of work about climate. After the 2024 floods, Greenlee joined RAFT, or Recovery After Floods Team, a group of volunteers in Huntington, Richmond and Hinesburg that is helping flood survivors with long-term recovery. She sees her cyanotypes as the artistic counterpart to that on-the-ground work.

“My response as an artist is ‘How do you process that amount of grief — ecological grief and grief in general?'” she said. “What have we lost? What can we change? How do we work together? I want my work to be part of that conversation.”

Among a series of nine cyanotypes titled “In Praise of Small Streams,” made at Johns Brook last winter, hangs “Come to the Brook,” a poem by Amy Seidl. Greenlee requested it of her friend and neighbor who codirects the University of Vermont’s environmental program. In it, the brook is a unifier — not just of the wild animals that visit it but also of humans and plants, whose exhalations mingle with the brook “as it rises into air.”

“It’s a cliché, but everything really is connected,” Greenlee said. “That’s hammered home for me by this work every time.”

This story was updated on January 29, 2025, to clarify that Greenlee has two master’s degrees.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content