In the barrenness of the winter months, SCAG (Southside Contemporary Art Gallery) provides a vivid contrast. Hull Street is alive with people hustling about the red brick buildings and snow-encrusted sidewalks. The gallery itself resembles a greenhouse, its entrance enshrined by the vines and leaves of potted plants. Sunlight cascades from the glass-paned windows and door, bathing the assortment of artwork in a soft curiosity. These pieces inhabit the walls, as well as a number of pedestals, and each is illuminated by its own distinct spirit.

This is Keep it 1000, a SCAG exhibit series aiming to provide accessible entry into the world of contemporary fine arts for artists, collectors, and other community members. Each piece is priced at or around $1,000, a price that lends itself both to the artists and those purchasing. This particular installment was on display through December and January—one of the more transformative times of the year—and featured the artwork of eleven emerging artists from across the country. Together, the artworks entwine family, politics, gender, race, self-reflection, and unity. The variants of color, style, medium, and personality are braided together by an undercurrent of vibrancy and strength. The exhibit features painting, collage work, ceramics, chicle (the main ingredient in chewing gum), and various other mixed media. As a group exhibition, it not only showcases the diversity of material usage but also the conceptual uniqueness of each artist.

The exhibition series curator, Ra-Twoine (Rosetta) Fields, emphasizes that the goal of the gallery isn’t just about “accessibility for the artists, but for everyone.” The gallery can therefore serve as a way to, in Rosetta’s words, “synchronize the ecosystem.” He elaborates,

“We really have an ecosystem in Richmond, that’s undeniable, but it’s just not as synchronized as it could be.”

As abundantly diverse as Richmond is, the ecosystem Rosetta speaks of remains in a state of imbalance. That is why places like SCAG are so important. The gallery is located at the intersection of the historically African American Manchester/Blackwell districts and prioritizes promoting BIPOC artists. Their emphasis on accessibility offers a space for those too frequently left unheard, and the reality portrayed by those without easy avenues of exposure gifts the art world a far more authentic, real, and full picture of humanity. This is particularly vital in a modern atmosphere of superficial overconsumption and inequality.

Near the front window billows Floridian artist Jillian Marie Browning’s rel-a-tive #13, a cyanotype that stretches from ceiling to floor. The cotton fabric work embraces the power of a mother-daughter bond and the mystical connection between generational continuation and pregnancy. The piece radiates with a bright blue imprint left from the sun, an essential component of the cyanotype process. In her statement on the series, she writes:

…I reflect on the idea that when I was being formed in the uterus of my mother, my body was also creating my reproductive organs, which were forming my ovum. As my fetal cells were dividing and replicating, her chromosomes were copied into the fiber of my DNA. In turn, when my mother was developing inside her mother, her body was also forming her ovum—one that would eventually become me. Forming a connection from grandmother, mother, and child many years before I would ever be conceived.

The imprint of sunlight, a cyclical natural force, mirrors this idea of generational continuity within the womb—the reproductive system producing further reproductive systems at a minute scale. It is a cycle, but also an infinite line. Ferns and leaves border the piece, reinforcing the repetitious pattern of growth in plants and how this can also be seen in human reproduction, whether through personality traits or appearance. The piece casts light on the promise of future procreation, the carrying of cells as well as hope.

As a supplement to the exhibit, SCAG also provides an educational program called Art Collection 101 for aspiring collectors, artists, and the community in general. The program’s aim is to provide resources and knowledge on different areas and methods of stewardship and collection, as well as to introduce them as feasible ventures. The gallery also offers payment plans and allows for holds to be placed on works to increase affordability for those seeking to purchase. The gallery’s overarching desire is to create an inclusive opening into the fine art world and to be a welcoming space for everyone.

Located on a pedestal towards the left of the gallery desk stands a sculpture by Zimbabwean artist Nyasha Chigama, titled Power of the Incapacitated. The sculpture, or vespture (a term coined by Chigama to describe a combination of vessel and sculpture), examines the dynamics of hierarchy and the interplay between power structures and the rest of society. This balance is shown through highly contrasting colors—black and white—much like a remolded yin-yang. She says in her statement that the piece “serves as both a declaration and an inquiry. Through the use of contrasting colors, [she aims] to examine the power dynamics inherent in racial politics from the viewpoint of an African woman.”

Composed of clay, latex, pencil, and glaze, the vespture takes on a minimal nature, addressing these dynamics in a straightforward manner while remaining open to interpretation due to the ambiguity of its shape. The form seems to morph like a Rorschach test—is it a scale, an animal, ovaries? The answer becomes the viewer’s to ascertain, calling into question how we perceive these power dynamics on an individual basis.

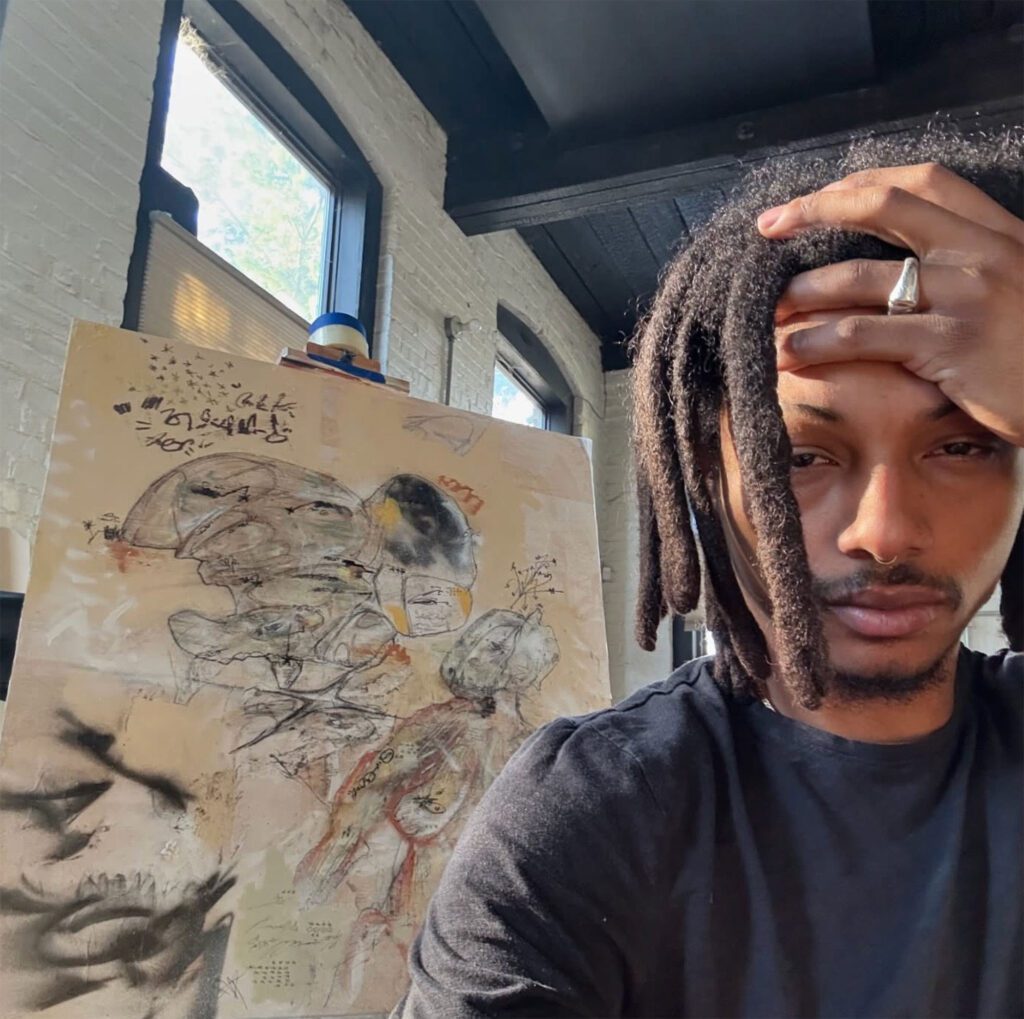

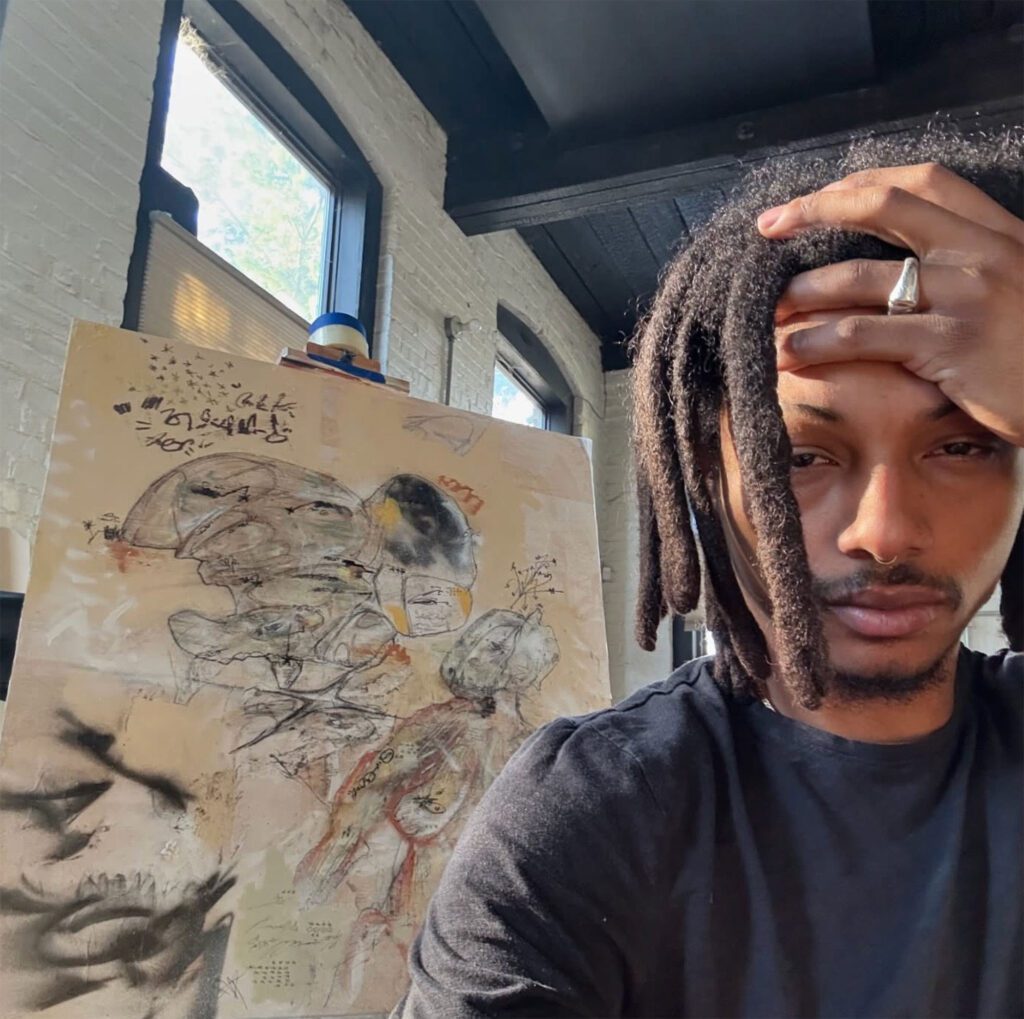

On the opposing wall, Philly-based Huey Lightbody’s mixed media piece is a flurry of notation, resembling an architectural blueprint, only the structure in the center appears to be in the process of transformation. Similar to Chigama’s piece, the shapes emerging from this central mass are ambiguous. However, there is continuous movement. As the eye moves from one corner to another, there is a sense of urgent processing taking place—an internal taking and digesting of information, perhaps past a comfortable speed.

Lightbody describes his work as Brutalist, a genre of art that emphasizes utilitarianism and raw material. Primarily associated with the architectural movement spanning the 1950s and ’70s, Brutalism initially developed during the post-WWII era, when resources were scarce. The movement rejected ornate decoration, opting for a less superfluous, more elemental look. It is also linked to Socialist Utopian ideals, with many early Brutalist buildings being affordable housing projects. These ideals are further expressed in Brutalist work, which is structural, raw, and confrontational.

Similarly, Lightbody explores in his piece a segment of life that takes over many of our minds to the point of determining the underlying structure of our everyday existence. The piece’s title, Rent, along with the repetitious numbers scratched near its edges, suggests the passing of months marked by monetary figures—time being notated by an abstract concept: money. In his statement, he speaks of “survival mode.”

“When peace is at stake, the flow survival brings almost feels like dance. Natural movements come through in guidance. When we understand our affliction, we realize survival is what carries us, and all else beyond that is where we thrive.”

Visitors to the gallery move through the space haphazardly, intuitively gravitating toward whichever piece catches their eye. The beauty of Keep it 1000 is that there is something for everyone. Its variation reflects the expanse of possibility created when people come together with different ideas, experiences, and realities. This is a place where voices can be celebrated. Furthermore, Rosetta wants SCAG to be a place where all members of the community can feel they belong.

“People want to feel welcome and safe,” he says. “Whether they have a million dollars in their pocket or not, they want to feel like they can come somewhere and no one’s going to judge them, no one’s going to pressure them, no one’s going to isolate them in different ways… That’s been really important for us.”

Keep it 1000 is not only an expression of the artwork in the gallery but of hope within a community. It demonstrates that accessibility and education aren’t made prosperous through individualism but instead through unity and neighborly love.

Keep it 1000 will return in 2026 for its third installment. Viewing of the exhibit remains available through the digital exhibit catalog.

Written by Maria Snell-Feikema

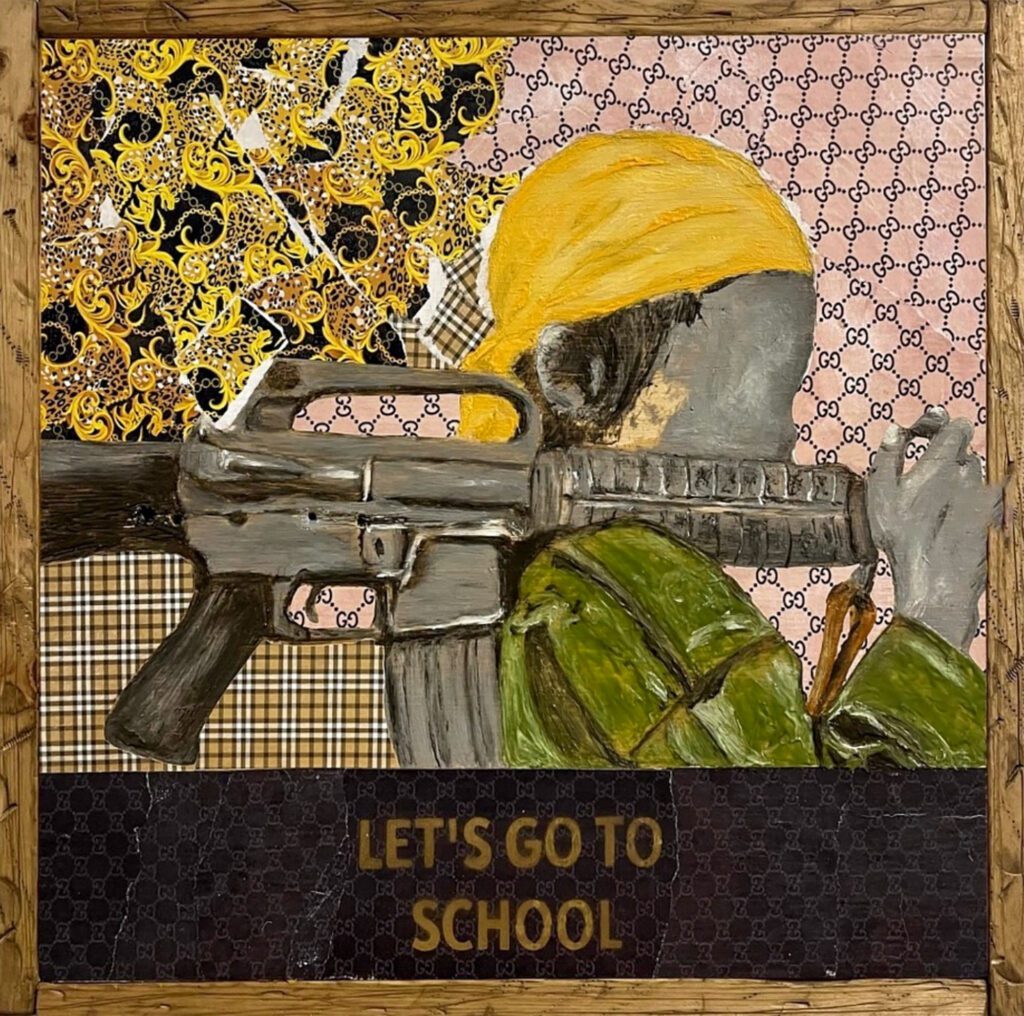

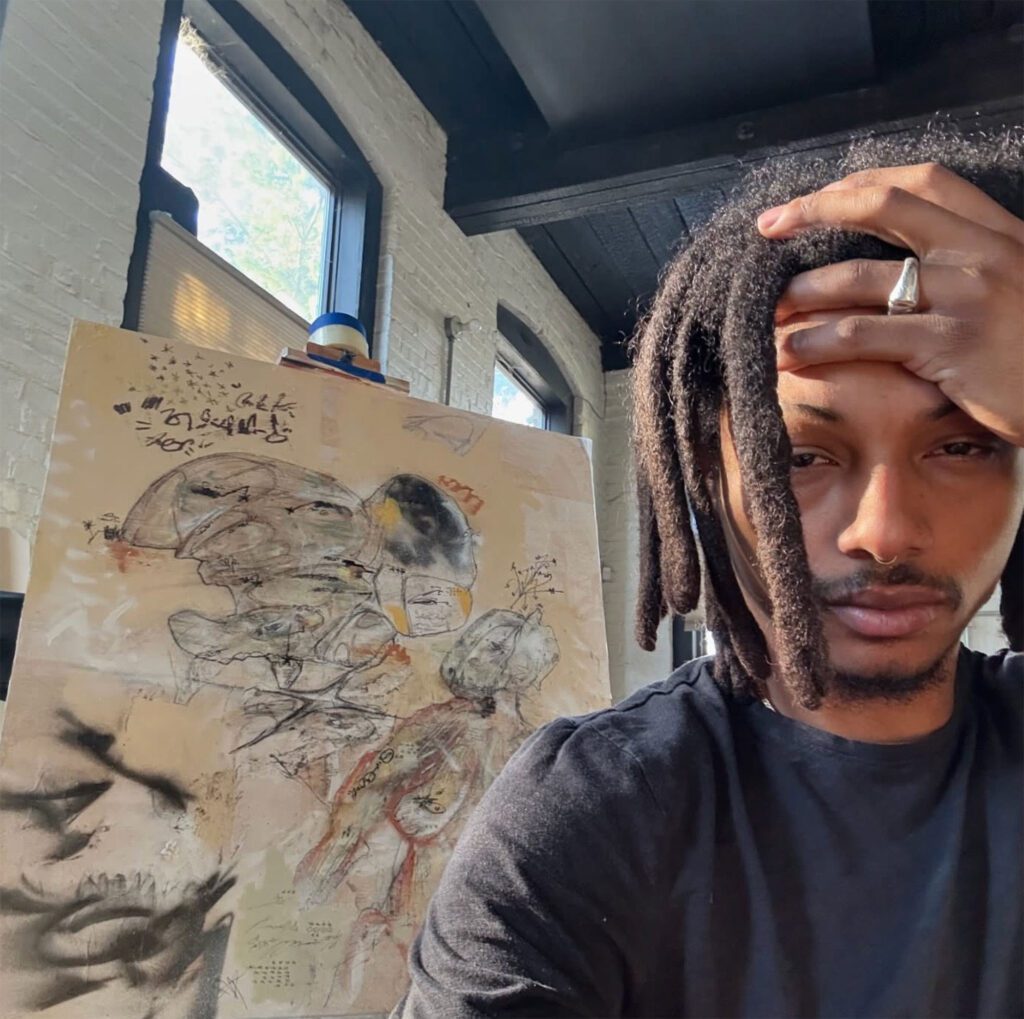

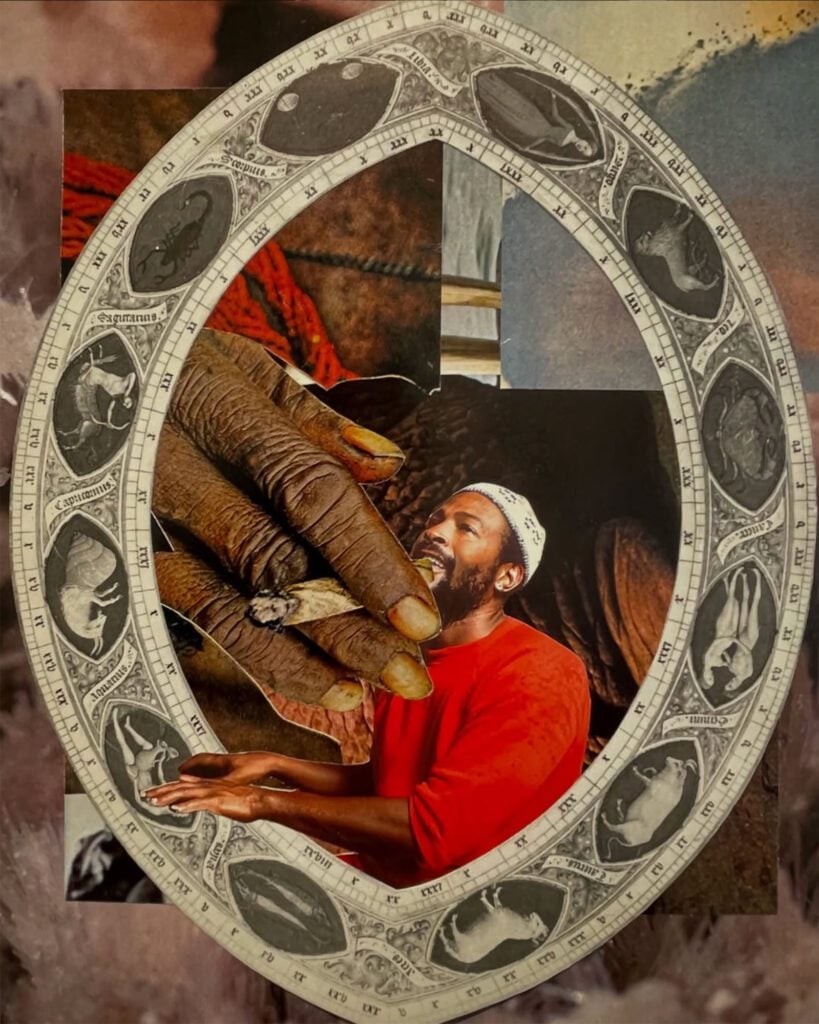

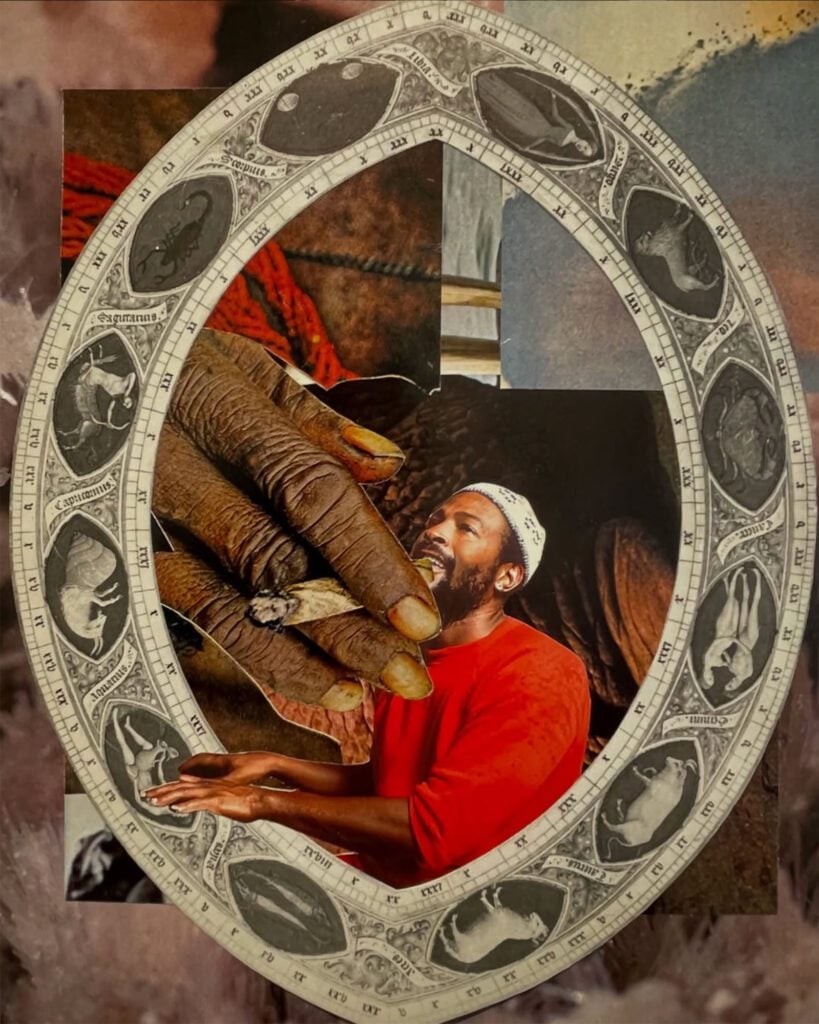

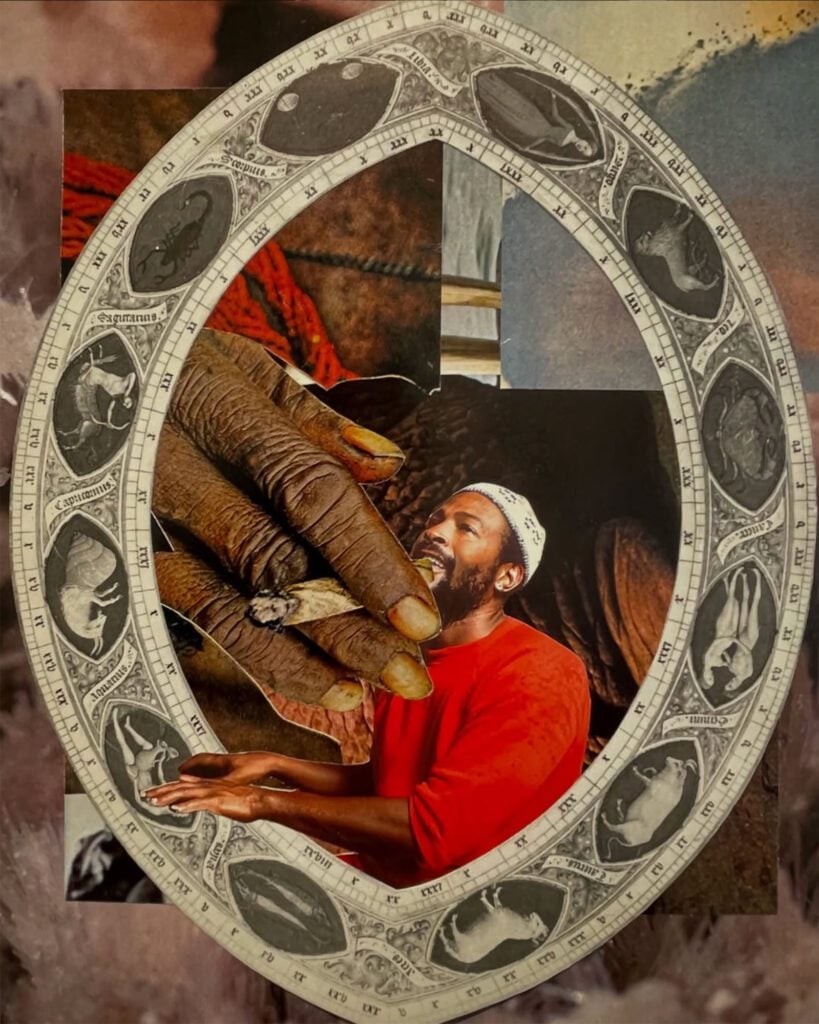

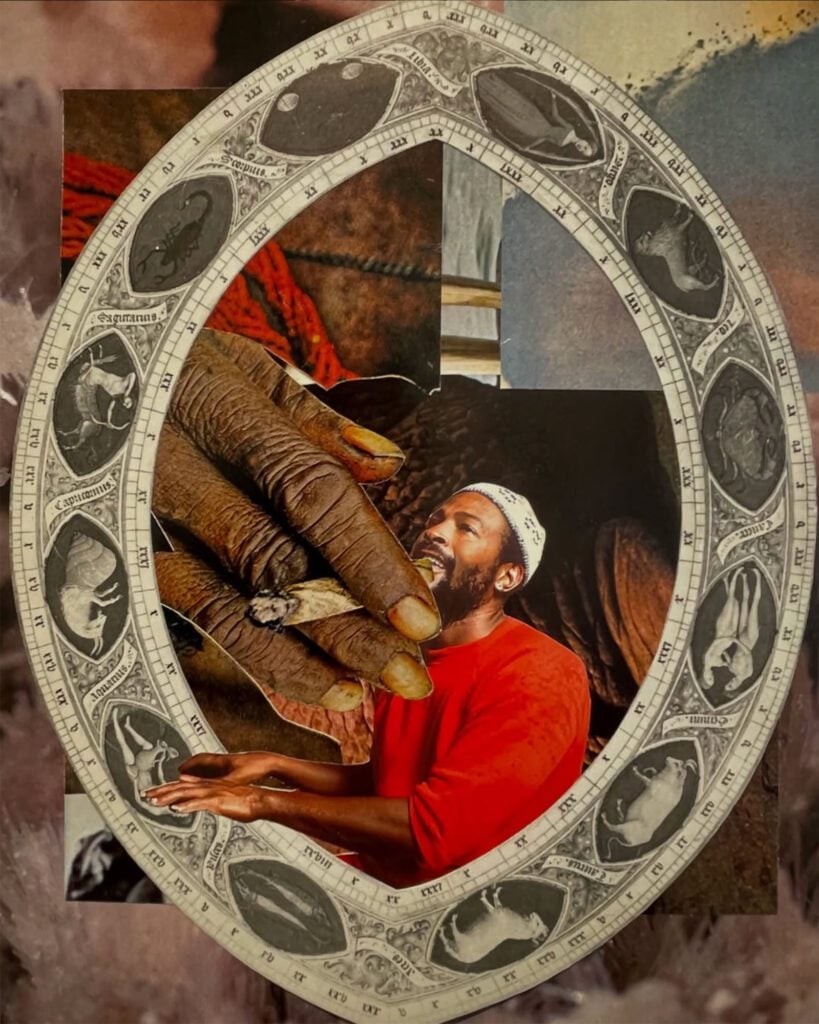

Main image features work from Rain Spann

Support Richmond Independent Media Like RVA Magazine

In a world where big corporations and wealthy individuals shape much of the media landscape, RVA Magazine remains fiercely independent, amplifying the voices of Richmond’s artists, musicians, and community. Since 2005, we’ve been dedicated to authentic, grassroots storytelling that highlights the people and culture shaping our city.

We can’t do this without you. A small donation, as little as $2, – one-time or recurring – helps us continue to produce honest, local coverage free from outside influence. Your support keeps us going and keeps RVA’s creative spirit alive. Every dollar makes a difference. Thank you for standing with independent media. DONATE HERE

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content