“Rogues and Scholars,” James Stourton’s erudite and authoritative history, doesn’t spare the color.

ROGUES AND SCHOLARS: A History of the London Art World: 1945-2000, by James Stourton

An art dealer I know blames Ozempic for the recent slump in sales: Collectors haven’t been hungry.

After reading “Rogues and Scholars,” James Stourton’s erudite and authoritative history of the London art market from World War II to our century, I’m inclined to agree. Stourton, for decades a former chairman at Sotheby’s UK, makes clear that, although all buying is appetitive, auctions turn personal cravings into group binges, with global effects.

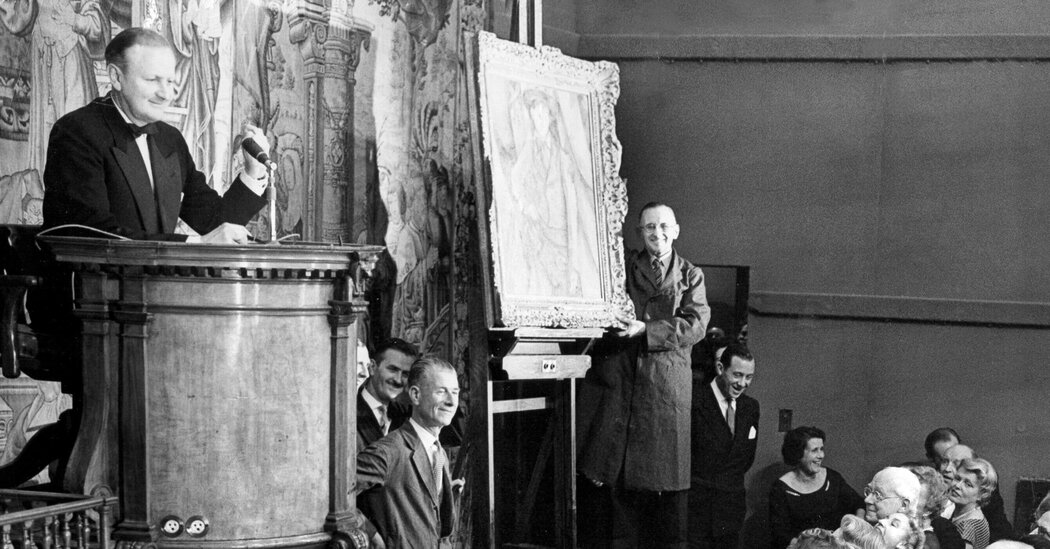

His Year Zero is 1958, when Sotheby’s auctioned the German banker Jakob Goldschmidt’s Impressionist paintings. While only seven works were offered, the black-tie crowd and TV cameras made it a spectacle. One Cézanne, sold for 220,000 pounds, set a new auction record. The night was a turning point, Stourton suggests, when auctions, formerly quiet industry affairs supplied mainly by country estates, became celebrity events. It also goaded a rivalry between Sotheby’s and Christie’s that endures today.

Both houses dated to the 18th century, but Christie’s was older, more prestigious, known for its paintings. Sotheby’s, initially specializing in books, was transformed under Peter Wilson, who became chairman in 1958. A debonair unmoneyed aristocrat and former MI6 operative, Wilson understood branding and embraced pure commercialism, even licensing the firm’s name for cigarettes.

His rival, the Christie’s chairman Peter Chance, was a former army officer, and stuffier. His firm fostered client loyalty by retaining staff, but suffered from “lackluster expertise,” writes Stourton, until they started to recruit Cambridge art history graduates. Stourton reports the industry gossip: “When somebody died, Peter Chance went to the funeral, and Peter Wilson went to the house.” Chance on Wilson: “That man is a swine.” Wilson’s motto? “Leave nothing to Chance.”

With improvements in travel and technology, milestones of commerce were vaulted, and each appeared to cheapen a onetime gentleman’s sport. Sotheby’s 1964 acquisition of the New York firm Parke-Bernet broadcast a message of “world domination.” To attract reluctant buyers, Wilson began publishing indexes in the London Times stock pages: Renoir up, say, 405 percent, Monet up 1,000. In 1975, Wilson and Chance seemingly conspired to invent the buyer’s premium, using the reduced commissions to attract sellers, appalling dealers.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content