A new book called Modern Women: Flight of Time, edited by Julia Waite, is a survey of the women artists who have shaped the development of modern art in Aotearoa. In this excerpt, Stuart McKenzie talks about his obsession with A Lois White.

When I moved to Wellington in 1988 to complete a degree in religious studies, I answered an ad in the paper for a part-time job at the National Art Gallery. I started work in the small Registration Department, which was in the process of condition-reporting the collection. This involved removing paintings from dusty racks, crates and cupboards and checking them against the info cards on file. One day, I unpacked a painting by A Lois White (1903–1984): Winter’s Approach, circa 1939, oil on canvas, registration number 1984-0031-1, purchased with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds…

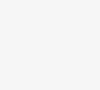

Forget the stats! Standing in that shadowy back room, I was set alight by the glowing colours, graphic intensity, force and figuration of this primal scene. The painting seared itself on my consciousness, even as it seemed to rise directly from my unconscious. I have been quietly obsessed by White’s work ever since.

Anna Lois White was born into a comfortable middle-class Auckland family. Her father Arthur was an architect and her mother Annie a shining light of the Mt Albert Methodist church. But after White’s father died, in 1920, the family was reliant on financial assistance from relatives. Graduating from Elam School of Art and Design in 1928, White became a tutor at the school. She continued to live with her mother and sister Gwen, supporting them financially. White never married. Art historian Nicola Green writes, “Throughout her life Lois struggled to reconcile two sides of her personality: the God-fearing dutiful daughter and the creative artist.”

I was struck by the bold sexual impulse in Winter’s Approach, painted when White was in her mid-30s. The older woman, arms outstretched like a puppet-mistress, seems to conjure the stripped girl from her imagination. They both have their eyes closed as if in a shared dream. The environment itself, with twisting trees and grasping branches, performs and amplifies the human drama of innocence and age, blossom and decay. Is it sinister and predatory? Or is it a mute irruption of feeling in which the women enact their forbidden desire for each other, heavy heads falling to one side in a powerful twinning of emotion?

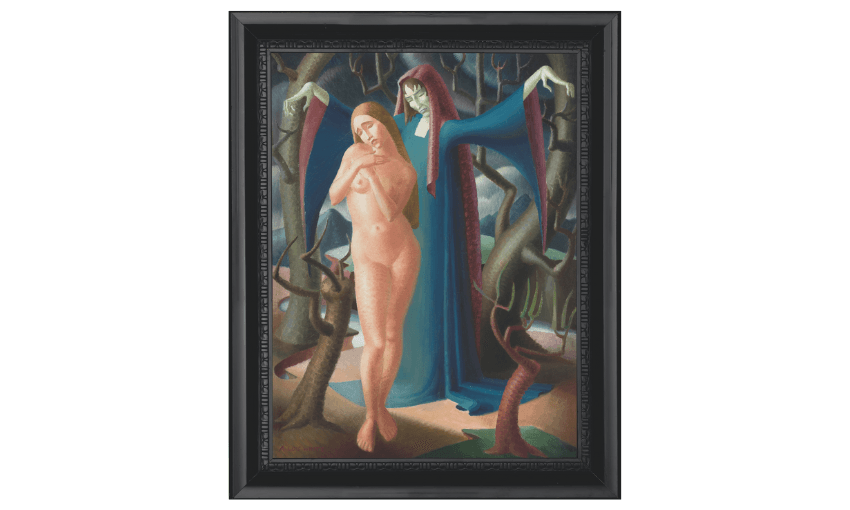

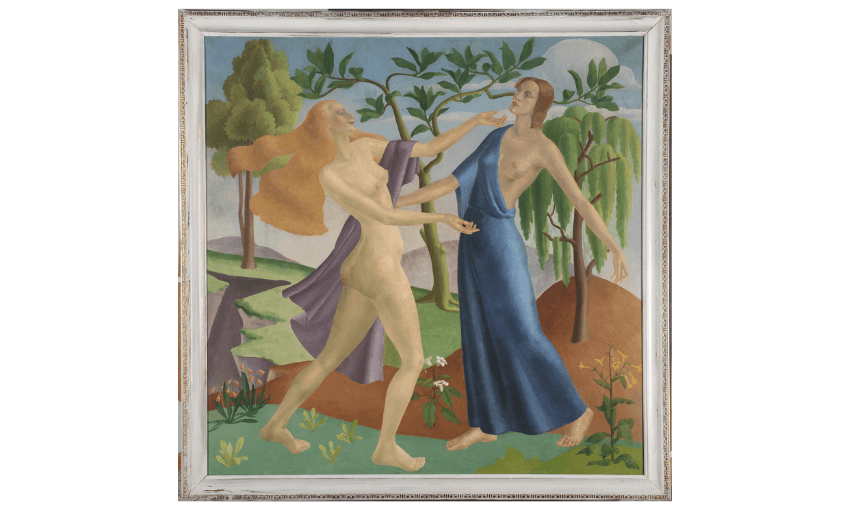

Winter’s Approach harks back to Persephone’s Return to Demeter, 1933, which White had exhibited at the Auckland Society of Arts. It was her coming out as a figure painter – not long before figuration in New Zealand art was overtaken by masculinist abstraction. Ostensibly, both paintings are about seasons passing. One draws on personal mythology and global current events to depict the arrival of winter, the other on classical mythology to depict the arrival of spring and personal awakening.

Abducted and forcefully married to Hades, god of the underworld, Persephone is confined there while her grief-stricken mother Demeter, goddess of crops, refuses to let anything grow. When Persephone is released from the underworld for a limited time each year, by decree of her father Zeus, she rises up into her mother’s arms and the world springs to life again. Contrary to the usual traditions of Renaissance art, in which Demeter and Persephone are depicted fully clothed, White paints the women rushing to embrace while shedding their costumes. Intriguingly, mother and daughter also look about the same age. Green suggests in her monograph on White that the figures are modelled on the artist herself and her inseparable friend and fellow artist, Winifred Simpson.

Desire quickens, new leaves burn green, the lilies in the field symbolise rebirth – but what we actually see are two women frozen in time, never to touch. Whether the two are maiden and mother, or lover and lover, Persephone’s Return to Demeter lingers on the moment before they clasp. Not even their eyes touch – each looks beyond the other, as if in a dream or drawn by an unconscious force.

What is both excited and proscribed here is desire. White’s paintings are beautiful machines in which desire is sparked then courses through a circuitry of recurrent patterns, exaggerated gestures and deferred glances. And here’s the thing – easy to overlook, but unmistakable on further viewing: in White’s whole oeuvre, her figures never look directly at each other. Perhaps if they were to hold each other’s gaze, desire would have to acknowledge itself as intercourse.

The exceptions that prove the rule are White’s self-portraits in which she looks directly at us, her viewers, as if willing us to share her secret. Sometimes shown clothed, once bare-breasted, almost invariably painting at her easel, the artist in her self-portraits urges us to look at her with the same intensity with which she fleshes out her female models.

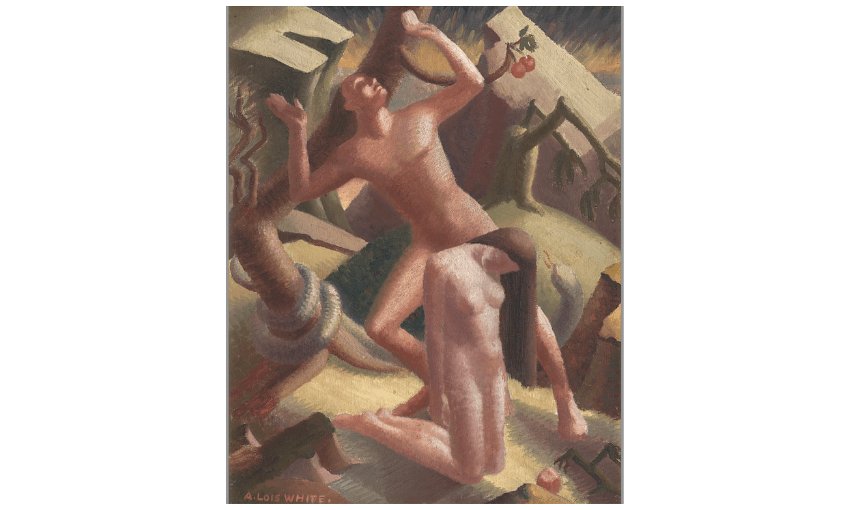

White’s Expulsion, circa 1939, was, like Winter’s Approach, painted as world war loomed. The parallels and connections between the two works shimmer and fizz, not unlike the rhythms and patterns she puts in play within each painting itself. In the Greek myth, Persephone eats the forbidden pomegranate seeds, and so is charged to return each year to the world of the dead. Likewise, Eve eats the forbidden apple, and is punished with mortality. In Expulsion, White shows Eve kneeling in shame, in stinging nakedness, a degraded penitent in a spectacle wrought by a de Sadean god. Her hair is a fig leaf to Adam’s manhood and the offending fruit lies abandoned before her, while two remaining apples hang like balls on the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

But look closer – is this Adam or madam? As Green has observed: “Adam’s relatively androgynous body suggests that a female model may have been used.” Insinuated into this archetypal drama of heteronormative fall is, once again, an undercurrent of homosexual desire.

Through her references and subject matter, it would be easy to judge White as conformist, provincial and pious. But often what seems conventional can be most radical. What we think we see in White’s work is the world as it is ordained by the establishment, but secretly she’s showing us the world she wants, in which wanting is key.

The more White’s style changes, and it does – classical, decorative, social realist, expressionist, fanciful, pastoral – the more we come to see her as irrefutably herself, a determinedly single woman and a fiercely singular artist.

Modern Women: Flight of Time is edited by Julia Waite ($65, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki) is available to purchase from Unity Books.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content