Breasts have been a focus in the culture wars of the last 50-odd years. Second-wave feminists casting off their bras in the 1970s come to mind, and then ongoing judgment-filled debates around breastfeeding, and the even more fraught, and recent, hostilities around trans healthcare. Recent celebrations of female sensuality manifested in things like #freethenip, hot girl summer, widening conversations around sexual pleasure, and the body positivity movement all take breasts as a key motif, too.

But for all the girlies freeing their nips on Instagram, it’s much rarer to see them free on the street. We keep them under wraps and rarely articulate why they seem to be so contentious. The potency of breasts as symbols of things as disparate but overlapping as gender, eroticism and motherhood makes them the nexus of a wild cocktail of emotions, politics and desires.

A new exhibition at ACP Palazzo Franchetti in Venice, Breasts, sets out to examine the multifaceted ways artists have represented them. It’s a huge idea, but curator Carolina Pasti largely limits the exhibition to postwar modern and contemporary art. She’s sourced minor works from big name artists and installed them in a kitschy pink environment that isn’t even that Instagrammable, hoping to pull in visitors with the gimmick of boobs.

She begins, however, with a tiny Madonna and Child from circa 1395 that is part of the genre known as a Madonna del Latte because it depicts Christ drinking from his mother’s breast. There are hundreds of works like this one – it feels as if every Renaissance painter made one at some point. The iconography of the nursing madonna was a branch of the cult of the Madonna of Humility, because the Virgin Mary was depicted as a humble woman of the people. In medieval and Renaissance Europe (and even into the 20th century), breastfeeding was something only working-class people did: they breastfed their own children and were hired as wetnurses for middle and upper-class families. The idea that Mary would have nursed her own child, the son of God, was revelatory. The Catholic fascination with blood found resonance in another fluid of the body: milk.

But this motif fell out of fashion after the Council of Trent, also known as the Counter-Reformation, in the 1560s, which firmly delineated the boundaries of acceptable iconography in the Catholic church in response to the birth of Protestantism. The intimacy of Mary feeding her child, and the rapture in which these images were held by the masses, had become too crass, too prurient, too embodied for the church.

So begins the saga of the breast in modern western culture: already rife with conflict. Of course, Pasti could have started much earlier: with the so-called Willendorf Venus, for example, made circa 25,000 BCE in Paleolithic Europe and depicting a female figure with voluptuous breasts, belly and hips. Or with one of the many sculptures of the Ephesian Artemis, a version of the Greek goddess Artemis with many breasts, made around the first century CE. These ancient, pre-Christian images of women offer narratives of fertility, abundance and matriarchal power that sit outside the bounds of contemporary representations of femininity but nevertheless have influenced the way breasts are understood today.

In the centuries between Madonna del Latte and the modern and contemporary visions of the breast on show at Palazzo Franchetti, perceptions of breasts shifted dramatically. Think of the history of women’s necklines in Europe as a microcosm of the way breasts were socially coded: the high ruffs in early Elizabethan England compared with the busty, dramatically low necklines of 18th-century France that sometimes even exposed nipples, followed by the prudish late Victorian dresses, when high collars returned. Class is hugely important in reading this history, too: it was generally the breasts of upper-class women that were of interest, either as objects to be hidden or displayed. Images of women in lands that were colonised by European powers were often rendered with bare breasts, signifying their perceived lack of civilisation and their inequality with white women.

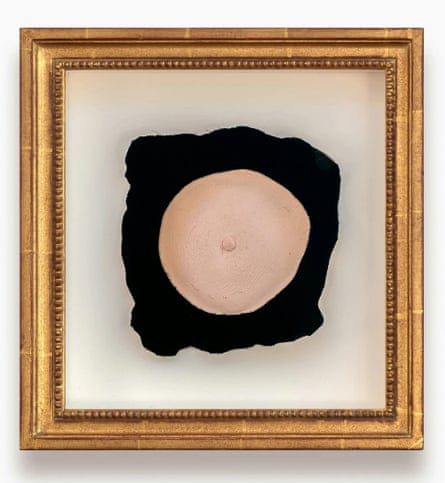

In the 20th century, the development of modern art and abstraction led to depictions of the breast that were abstracted from the body. Laura Panno’s work, which Pasti cites as the main inspiration for the show, depicts breasts in isolation, without the body they belong to. The shapes and textures that make a breast become strange and heightened in this context. The repeating concentric circles of Panno’s Origine echo Marcel Duchamp’s Prière de Toucher, which is also featured in the exhibition. The sense of roundness, of being an orb, which is rarely true of actual breasts, is highlighted in works such as Adelaide Cioni’s To Be Naked, Breasts and Masami Teraoko’s Breasts on Hollywood Hills Installation.

Despite the erotic association of breasts, few of these works are particularly sexual. Chloe Wise’s Soccer, showing a chest with a curvy set of breasts leaning down over a black and white soccer ball, has the most sex appeal. The disembodiment of most of these works is too jarring to allow for any sense of human connection.

The artist’s gaze takes on outsize significance here, when power dynamics and physical interaction are implied by the interaction between artist and subject. Pasti told me that inclusivity was a fundamental value for her as curator of this exhibition, in her pursuit of “understanding how women were represented throughout art” by both men and women.

The male artists featured in the exhibition approach the breast from various points of view. Robert Mapplethorpe, the celebrated gay American photographer, took the photo titled Lisa Marie/Breasts in 1987. He positioned himself and his camera below his subject’s chest, taking a photo that looks upward from her belly button towards her breasts, which rise up like mountains in a strange landscape of flesh. His insistence on the shape and line of this monumental embodied landscape, rather than the personhood of his subject, invites the viewer to see breasts from a new perspective. Other male depictions of breasts have an undertone of violence or control, such as Allen Jones’s Cover Story 2/4, a Barbie-esque metal cast of an idealised female body.

after newsletter promotion

While some artists look forward to abstraction or other contemporary visual languages, others look back to historical motifs of representing breasts. Cindy Sherman’s photograph Untitled #205 shows the artist dressed as a sort of baroque, Madonna-esque figure with bare breasts and pregnant belly draped in gauzy fabric, arranged like an Ingres painting. But the breasts and belly are obviously fake, hanging on the artist’s shoulders like those of a drag queen, evoking complicated readings about gender, motherhood, and transhistorical connections. Anna Weyant’s more recent painting, Chest, shows a closeup of a woman’s chest with her arm covering her breasts. The flattened realism and blank setting is characteristic of Weyant’s work, and gives her subject a timelessness that allows us to imagine it depicts a scene that is equally likely to have happened yesterday or 500 years ago.

The decision to examine a single part of the traditional female body, rather than the whole body or the idea of femininity or womanhood itself, makes this exhibition purposefully narrow. It promotes a particularly abstract, formal view of the breast: how has this beautiful, specific thing inspired artists? The curves, the colours, the undulations of skin and flesh are the subject of the works here much more than the cultural ebbs and flows of breasts and the people who have them.

It also opens up space for conversation about who has breasts. Prune Nourry is the only featured artist who is a survivor of breast cancer, and her work, Œil Nourricier #6, is a fragile, round glass sculpture of a breast that raises questions about the fragility of life and health. Many breast cancer survivors no longer have their own breasts, so the mobility of this sculpture reflects the way breasts can be something that is removed from the body.

Breasts can also be added to the body, as in Sherman’s photograph, or in Jacques Sonck’s photograph of a trans woman in Ghent. Sonck’s photo of a bare-chested man is also included, reminding us that literally everyone has breasts of some shape or size – but when we say “breasts”, we almost always mean women’s. These works push at the biological essentialism that still undergirds the way we think and talk about gender and bodies. If breasts can come and go from bodies of different gender identities, how does their cultural meaning evolve?

The exhibition joins a larger trend in the art world of exploring embodiment, which has often been driven by female artists and a feminist gaze. This has led to some wonderfully nuanced and substantive explorations of bodies and gender in art, such as Lauren Elkin’s recent book Art Monsters, but also to a lot of posturing about bodies that is only skin deep. Women’s bodies have been the central motif of western art, and critical engagement with those women is long overdue. Boobs are just boobs without the person they belong to – but what about her? What does she think?

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content