By Clare Thorp

Alamy

AlamyFifty years ago, Abba was triumphant at Eurovision – but a new documentary shows just how bittersweet that victory was.

It’s been 50 years since Abba arrived onstage at the Eurovision Song Contest – all satin, spangles and silver boots – and marched to victory with their song Waterloo. In a stroke of luck, this year’s contest takes place in Sweden, setting the scene for a suitably glittering celebration of their country’s biggest musical export.

Organisers of this year’s event are planning to thank Abba for the music by way of a tribute performed by three previous Eurovision winners: Charlotte Perrelli, Carola and Conchita Wurst. It’s not clear whether we’ll see an appearance from Agnetha Fältskog, Björn Ulvaeus, Benny Andersson and Anni-Frid ‘Frida’ Lyngstad, too. Last year Björn and Benny dismissed the idea of a reunion for the contest, and the band haven’t performed together for over 40 years. But fans are hopeful they might see the band — even if only in the form of the digital avatars that have thrilled hundreds of thousands at the Abba Voyage virtual concert in London.

After all, no other Eurovision winner has come close to matching the success of Abba, who since winning the contest in 1974 have sold 385 million records and become one of the most successful bands of all time. A recently unveiled commemorative blue plaque on the Brighton Dome marks the spot where Abba “launched their career after winning the 19th Eurovision Song Contest”. But, as a new documentary about the band shows, the victory was bittersweet, and the start of an uphill battle to get their music taken seriously. “The mythology around Abba has become very much that they were always destined for stardom,” James Rogan, director of Abba: Against the Odds – which draws on rare archive footage and interviews – tells the BBC. “Eurovision was a huge milestone on the road to stardom, but they immediately ran into massive headwinds after winning.”

Alamy

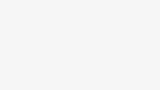

AlamyThe foursome formed in 1972, and tried unsuccessfully to enter Eurovision in 1973 with their song Ring Ring. Seeing the contest as their ticket to success outside of their own country, they pulled out all the stops the following year, writing Waterloo specifically for Eurovision. It paid off. Not only did they win in Brighton, but Waterloo was a number one single in the UK (despite receiving nil points from the UK voting jury) and topped the charts all over Europe.

Yet in the film, Benny recalled how the UK initially saw them as “quite beige”, saying: “Even if the song was number one in England, if you’re part of Eurovision, you’re dead afterwards.” Radio DJs were reluctant to play the band’s music, and it would be more than 18 months before they had another number one with Mamma Mia. Eurovision was proving to be a double-edged sword. The outfits, as fabulous as they were, perhaps didn’t help. “We weren’t taken seriously, I think because we were wearing such strange clothes,” says Björn. “The kitsch… we really suffered for that.”

Backlash at home

But it was in their home country where Abba – who shared their name with a Swedish brand of pickled herring – faced some of the biggest animosity. “It was a different mass-media climate in Sweden at that time,” says Björn. “We were not popular.”

Alamy

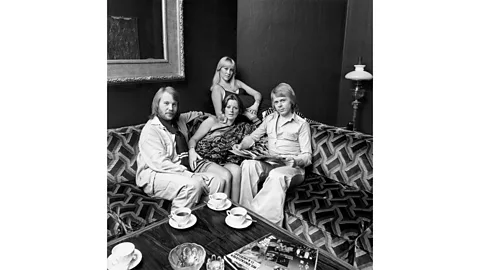

AlamyArchive footage in the documentary shows Swedes being asked their opinions on the band. “They’re too commercial,” answers one man. “They only sing pop,” says a woman. The band were viewed by many as manufactured and only in it for the money. Before joining Abba, Björn and Benny were both in popular folk groups, while Agnetha and Frida were successful in their own right. “And then they came together in this kind of glitzy glam bubblegum pop formation,” says Rogan, who likens the backlashto the outcry over Bob Dylan going electric.

Another issue was that, as per the Eurovision rules, Sweden was due to host the contest the year after Abba’s win. “The fact that they had won meant that [public broadcaster] SVT then had to fund Eurovision,” says Rogan. “This musical culture which regarded itself as authentic and sort of folksy suddenly saw the funding dry up for their projects and Eurovision sucking it all up.”

A left-wing movement called Progg, which campaigned against the commercialisation of music, protested against the contest coming to Sweden, with 200,000 people taking to the streets of Stockholm. On the night of the show, there was an alternative music festival hosted on the other side of the city. “There was kind of a progressive movement that looked upon Abba as the Antichrist,” says Björn. Such was the power of the protests that Sweden decided not to enter the contest at all in 1976.

That Abba were apparently apolitical also riled many. “We were the upset generation,” explains Michael Wiehe, singer with Swedish group the Hoola Bandoola Band in the documentary. “We were upset about the apartheid system, we were upset about the military coups in Latin America, we were upset about the wars in South East Asia. And we were upset that Abba weren’t upset.”

Alamy

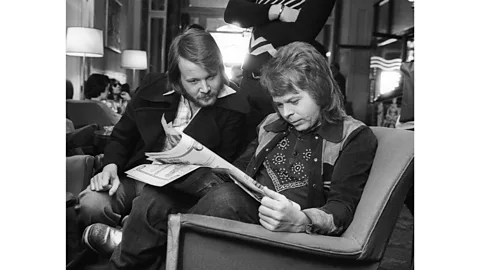

AlamyAll this meant that – though they did well commercially – Abba was somewhat of a dirty word among the music community in Sweden. “They were selling a lot of records and were hugely popular,” says Rogan. “But those records would then be hidden on the shelves. And some of the musicians who played with them were blacklisted.”

This sort of musical snobbery would plague them for years, not just in Sweden but around the world. Even as they racked up hit after hit, the press continued to be wary of the band, with press cuttings in the documentary featuring lines like: “We have met the enemy and they are them.”

Looking back over old interview footage, Rogan was shocked by how dismissive some reporters were. “If you had the opportunity to speak to Benny and Björn just after they’d written SOS and Knowing Me, Knowing You, would your questions be: ‘How poor are your lyrics? Do you like playing it? Isn’t it all a bit samey?'”

The frustration is often clear on the band’s faces. “What’s extraordinary about it is that these guys were inventing a sound,” says Rogan. “They were creating some techniques that would go on to fuel the Swedish music industry.”

It wasn’t just the press that was dubious of Abba. The band’s rise coincided with the emergence of punk, a movement totally at odds with Abba’s shiny pop image. And when Abba embraced disco with their Voulez-Vous album in 1979, it came as the “Disco Sucks” movement was trying to tear the genre down.

Alamy

AlamyAs Jeff Tweedy of the band Wilco wrote in an essay on his love of Dancing Queen for The New York Times: “As a kid who liked punk rock, this tune was situated deep in enemy territory, at the intersection of pop and disco.” And yet – just as it did for Tweedy – the song’s melody proved irresistible for even the staunchest punk rockers. In the documentary, it’s revealed that The Sex Pistols had the cassette playing on a loop when they were on tour. “The Sex Pistols were put together by their manager, so there’s a kind of musical paradox that this symbol of punk authenticity was listening to the symbol of pop inauthenticity, and one was manufactured and the other wasn’t,” says Rogan.

Indeed, many rock musicians were fans of the band. At their sell-out 1979 Wembley Arena show, members of Led Zeppelin and The Who were in the VIP area. Pete Townsend apparently called SOS “the best pop song ever written”, and it was also a favourite of John Lennon. “I think that the musicians cottoned on to what Abba were doing quicker than the critics did,” says Rogan.

By the time Abba released the album Super Trouper in 1980, critics were finally coming around to their songwriting skills. Songs like The Winner Takes it All – widely believed to be inspired by Björn and Agnetha’s divorce – epitomised what the band did best, combining emotionally devastating lyrics with addictive melodies.

It’s this deep sense of melancholy – something Benny once attributed to coming from a part of the world where the sun all but disappears for two months, and snow falls for nearly half the year – that has come to define their sound. In one clip in the documentary, an interviewer asks Aretha and Frida if they are happy. “Sometimes, sometimes not,” says Frida. “Life goes up and down,” adds Agnetha. This ability to reflect both the dreams and disappointments of life was Abba’s songwriting superpower.

Alamy

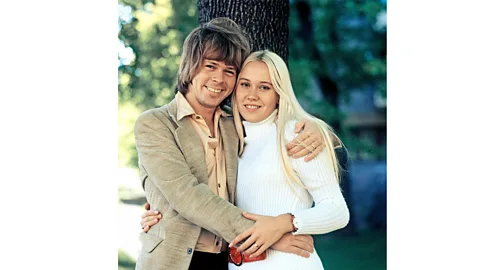

AlamyThe band split in 1982, following the separation of both couples. But the end of Abba the band was only the beginning of Abba the phenomenon. In 1992, they released their greatest hits collection Abba Gold – the second best-selling album of all time in the UK. In 1999, Mamma Mia!, the stage musical based on their songs, debuted, later spawning a hit movie. The ground-breaking Voyage show that opened in London in 2022 (following a surprise new album, Voyage) and is set to go on tour has been a tremendous success.

But, even more than the commercial success, they’ve achieved what eluded them for so long – respect as songwriters, and recognition for their huge impact on pop music. “All of those early criticisms have more or less melted away and the music remains,” says Rogan. “And the music is sort of a cultural juggernaut.”

As for Sweden, the country once so uneasy with the commercialisation of music has ironically become something of a pop music powerhouse, with producers like Max Martin creating hits for acts such as Britney Spears, Taylor Swift and Katy Perry. And it all started with Abba. “There is a sort of love-hate relationship with Abba in Sweden, but I think they’ve now been accepted as part of the cultural furniture,” says Rogan.

Whether the band themselves join in with the celebrations or not this weekend, does Rogan think they can now look back fondly on their Eurovision glory, despite the baggage it came with?

“I think Abba are the ultimate pragmatists. It was a pragmatic decision to go into Eurovision because it was the only platform that could launch them into the Anglophone world of music at that level. So I think in that sense, they have no regrets.”

Abba: Against the Odds is streaming in the UK on iPlayer and in the US on the CW Network from 11 May.